Home | Category: Pre-Islamic Arabian and Middle Eastern History / Pre-Islamic Arabia / Pre-Islamic Arabian and Middle Eastern History

NABATEANS

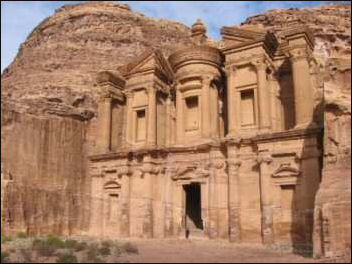

Petra Monastery

The Nabateans (also spelled Nabataeans) were a nomadic tribe who moved from Arabia to Petra in present-day Jordan around 2,400 years ago. They were major power in the the Middle East during the period between the decline of Greece and the rise of Rome. Little is known about the Nabateans. They lived primarily in a 1,000 square kilometer (400 square mile) area around Petra. They left behind no written record. Ancient manuscripts described them as smart merchants and traders.

Much of Nabatean culture has been lost to history. “We’ve all heard of the Assyrians, we’ve all heard of the Mesopotamians,” Wayne Bowen, professor of history at the University of Central Florida, told CNN. “But (the Nabateans) stood up to the Romans, they stood up to the Hellenistic Greeks, they had this incredible system of cisterns in the desert, controlled the trade routes. I think they just get absorbed in the story of the growth of the Roman Empire.” Though the Nabateans didn’t leave much behind in the way of historical documentation, one of their culture’s achievements continues to play a huge role in the region — the Nabatean alphabet laid the foundations of modern Arabic. [Source: Lilit Marcus, CNN, January 3, 2024]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Nabataeans: Builders Of Petra” by Dan Gibson Amazon.com ;

"Petra Rediscovered: Lost City of the Nabateans"edited by Glenn Markoe (2003) Amazon.com ;

“Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans” by Jane Taylor Amazon.com ;

“Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam” by Robert G. Hoyland Amazon.com ;

“Pre-Islamic Arabia: Societies, Politics, Cults and Identities during Late Antiquity”

by Valentina A. Grasso Amazon.com ;

“Gold, Frankincense, Myrrh, And Spiritual Gifts Of The Magi” by Winston James Head Amazon.com ;

“Frankincense & Myrrh: Through the Ages, and a complete guide to their use in herbalism and aromatherapy today” by Martin Watt and Wanda Sellar Amazon.com ;

“Inscriptional Evidence of Pre-Islamic Classical Arabic: Selected Readings in the Nabataean, Musnad, and Akkadian Inscriptions” by Saad D Abulhab Amazon.com ;

“The Ancient Near East: A Very Short Introduction” by Amanda H. Podany, Fajer Al-Kaisi, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East”

by Amanda H. Podany a Amazon.com ;

”History of the Arab People” by Albert Hourani(1991) Amazon.com ;

"Arabian Sands” (Penguin Classics) by Wilfred Thesiger Amazon.com

History of the Nabateans

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Straddling the northern end of the caravan route from South Arabia to the Mediterranean, the Nabatean kingdom emerged as a great merchant-trader realm during the first centuries B.C. and A.D. Previously nomads in northern Arabia, the Nabateans had already settled in southern Jordan by 312 B.C., when they attracted the interest of Antigonus I Monophthalmos, a former general of Alexander the Great, who unsuccessfully attempted to conquer their territory. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "Nabatean Kingdom and Petra", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000, metmuseum.org \^/]

By that time, the city of Petra (ancient Raqmu) was the center of the Nabatean kingdom, strategically situated at the crossroads of several caravan routes that linked the lands of China, India, and South Arabia with the Mediterranean world. The fame of the Nabatean kingdom spread as far as Han-dynasty China, where Petra was known as Li-kan. The city of Petra is as famous now as it was in antiquity for its remarkable rock-cut tombs and temples, which combine elements derived from the architecture of Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Hellenized West.

During the reign of King Aretas III (r. 86–62 B.C.), the Nabatean kingdom extended its territory northward and briefly occupied Damascus. The expansion was halted by the arrival of Roman legions under Pompey in 64 B.C. At various times the kingdom included the lands of modern Jordan, Syria, northern Arabia, and the Sinai and Negev deserts. At its height under King Aretas IV (r. 9 B.C.–40 A.D.), Petra was a cosmopolitan trading center with a population of at least 25,000. The kingdom remained independent until it was incorporated into the Roman province of Arabia under the emperor Trajan in 106 A.D.

Petra

the Treasury in Petra, center of the Nabataeans

Petra (180 kilometers south of Amman) was the center of the Nabatean kingdom. Jordan's number one tourist draw, this fabled sandstone city is an amazing place hidden among colorful canyons and carved into solid rock cliff faces in a remote valley. Described once as the "rose-red city half as old as time," Petra is composed on many structures, most of them tombs, scattered over a fairly wide area. It takes at whole to visit the site. Many people spend a couple of days there. [Source: Don Belt, National Geographic, December 1998]

Among the ruins carved into the rose- and chocolate-colored cliffs are the famous Treasury, a gigantic monetary, Roman-style palace tombs, soaring temples, elaborate tombs, a Roman theater carved into a cliff, burial chambers, banquet halls, water channels, cultic installations, markets, public buildings and paved streets. A few Bedouins still live in the ruins of some of the caves.

Petra was establish in the 4th century B.C. and flourished for 700 years. At its height during the Roman era, the Nabatean kingdom stretched as far north as Damascus and included parts of the Sinai and Negev deserts and ruled most of Arabia. Perhaps 30,000 people — a large number for an ancient city — lived hidden among the canyons in Petra, which was widely admired for its massive architecture and refined culture.

Word of Petra's wealth reached the Romans. In A.D. 106, the Emperor Trajan annexed the Nabatean kingdom into the Roman province of Arabia, with Petra as it's capital. By then Petra was declining as new trade routes that became part of the Silk Road opened to the north. When the city of Palmyra to the north in present-day Syria opened a major caravan route that connected with the sea trade routes from India and China, Petra declined quickly.

See Separate Article: PETRA: HISTORY, SIGHTS, ACHIEVEMENTS africame.factsanddetails.com

Nabateans in the Bible

The Nabateans are not mentioned directly in The Bible but their existence is implied and many states and peoples that they interacted with feature prominently in both the Old Testament and New Testament. The Nabateans were allies of the first Hasmoneans, of Hannukkah fame, in their struggles against the Seleucid monarchs. Nabatean towns of Moab and Gilead were the home of Moabites and Edomites, who are mentioned in the Bible.

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “The Nabatean displacement of Edomites prompted another Judaean, Obadiah, to express his feelings. The bitter memories of Edomitic behavior during the Babylonian conquest are revealed in the stinging words of what can best be identified as a hymn of hatred. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org]

“The bulk of Obadiah is generally placed in the first half of the fifth century B.C.. References to the sacking of Jerusalem (vss. 1 ff.) and to the same disruption of the Edomites mentioned in Malachi suggest the post-Exilic period. The intense nationalism is characteristic of other writings from fifth century Judah. The similarity between vss. 1-9 and Jer. 49:7-22 has led some scholars to suggest that both prophets adapted a pre-Exilic and anti-Edom hymn to their own use.10 The late R. H. Pfeiffer dated the last three verses of the poem in the fourth century,11 but they can just as easily be placed in the fifth century and attributed to Obadiah.

Mattahias and the Hasmoneans “The first nine verses of this poem mock the Edomites for the failure of their sources for security-remoteness, alliances, national strength. Now they have suffered a fate not unlike that which had come upon Judah in 586. According to Obadiah, the Nabatean attack was divine punishment for the role of the Edomites during the Babylonian conquest. Like other post-Exilic writers of this period, Obadiah believed that the Day of Yahweh was near when all aliens would suffer the wrathful punishment of the deity and only Judah would be saved to take possession of and rule in the new expanded kingdom. The fact that this poem was preserved probably indicates that it represented more than the view of a single individual and portrayed what was a rather common interpretation of events.

Some say the Petra is Biblical Sela. Sela (from Se'lah, rock) was the capital of Edom, situated in the great valley extending from the Dead Sea to the Red Sea (2 Kings 14:7). It was near Mount Hor, close by the desert of Zin. It is called "the rock" (Judg. 1:36). When Amaziah took it he called it Joktheel (q.v.) It is mentioned by the prophets (Isa. 16:1; Obad. 1:3) as doomed to destruction. Sela is identified with the ruins of Sela, east to Tafileh in Jordan (identified as biblical Tophel) and near Bostra, all Edomite cities in the mount of Edom. [Source: Wikipedia]

Sela appears in later history and in the Vulgate Version of the Bible under the name of Petra. "The caravans from all ages, from the interior of Arabia and from the Gulf of Persia, from Hadramaut on the ocean, and even from Sabea or Yemen, appear to have pointed to Petra as a common centre; and from Petra the tide seems again to have branched out in every direction, to Egypt, Palestine, and Syria, through Arsinoe, Gaza, Tyre, Jerusalem, and Damascus, and by other routes, terminating at the Mediterranean."

Nabateans In the Greco-Roman Period

The Seleucids (post-Alexander the Great Greeks) displaced the Ptolemies throughout Palestine , who in 198 B.C. Hostilities between the Ptolemies and Seleucids enabled the Nabateans to extend their kingdom northward from their capital at Petra (biblical Sela) and to increase their prosperity based on the caravan trade with Syria and Arabia. [Source: Library of Congress]

The new Greek rulers from Syria instituted an aggressive policy of Hellenization among their subject peoples. Efforts to suppress Judaism sparked a revolt in 166 B.C. led by Judas (Judah) Maccabaeus, whose kinsmen in the next generation reestablished an independent Jewish kingdom under the rule of the Hasmonean Dynasty.

Roman gate in Petra

By the first century B.C., Roman legions under Pompey methodically removed the last remnants of the Seleucids from Syria, converting the area into a full Roman province. The new hegemony of Rome caused upheaval and eventual revolt among the Jews while it enabled the Nabateans to prosper. Rival claimants to the Hasmonean throne appealed to Rome in 64 B.C. for aid in settling the civil war that divided the Jewish kingdom. The next year Pompey, fresh from implanting Roman rule in Syria, seized Jerusalem and installed the contender most favorable to Rome as a client king. On the same campaign, Pompey organized the Decapolis, a league of ten self- governing Greek cities also dependent on Rome that included Amman, Jarash, and Gadara (modern Umm Qays), on the East Bank. Roman policy there was to protect Greek interests against the encroachment of the Jewish kingdom.*

When the last member of the Hasmonean Dynasty died in 37 B.C., Rome made Herod king of Judah. With Roman backing, Herod (37-34 B.C.) ruled on both sides of the Jordan River. After his death the Jewish kingdom was divided among his heirs and gradually absorbed into the Roman Empire. In A.D. 106 Emperor Trajan formally annexed the satellite Nabatean kingdom, organizing its territory within the new Roman province of Arabia that included most of the East Bank of the Jordan River. For a time, Petra served as the provincial capital.

The Nabateans continued to prosper under direct Roman rule, and their culture, now thoroughly Hellenized, flourished in the second and third centuries A.D. Citizens of the province shared a legal system and identity in common with Roman subjects throughout the empire. Roman ruins seen in present-day Jordan attest to the civic vitality of the region, whose cities were linked to commercial centers throughout the empire by the Roman road system and whose security was guaranteed by the Roman army. After the administrative partition of the Roman Empire in 395, the Jordan region was assigned to the eastern or Byzantine Empire, whose emperors ruled from Constantinople. Christianity, which had become the recognized state religion in the fourth century, was widely accepted in the cities and towns but never developed deep roots in the countryside, where it coexisted with traditional religious practices.*

Strabo on the Nabateans

Strabo (64 B.C. – c. A.D. 24) was a Greek geographer, philosopher, and historian who came from Asia Minor at around the time the Roman Republic was becoming the Roman Empire. Strabo is best known for his work Geographica ("Geography"), which describes the history and characteristics of people and places in different regions known during his lifetime, [Source: Wikipedia]

Strabo wrote in A.D. 22:“XVI.iv.21. The Nabataeans and Sabaeans, situated above Syria, are the first people who occupy Arabia Felix. They were frequently in the habit of overrunning this country before the Romans became masters of it, but at present both they and the Syrians are subject to the Romans. [Source: Strabo: Geography, Book XVI, Chap. iv, 1-4, 18-19, 21-26, c. A.D. 22, Strabo, The Geography of Strabo: Literally Translated, with Notes, trans. by H. C. Hamilton & W. Falconer (London: H. G. Bohn, 1854-1857), pp. 185-215]

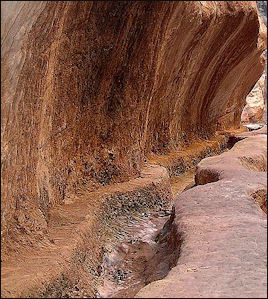

Petra aqueduct “The capital of the Nabataeans is called Petra. It is situated on a spot which is surrounded and fortified by a smooth and level rock (petra), which externally is abrupt and precipitous, but within there are abundant springs of water both for domestic purposes and for watering gardens. Beyond the enclosure the country is for the most part a desert, particularly towards Judaea. Through this is the shortest road to Jericho, a journey of three or four days, and five days to the Phoinicon (or palm plantation). It is always governed by a king of the royal race. The king has a minister who is one of the Companions, and is called Brother. It has excellent laws for the administration of public affairs.

“Athenodorus, a philosopher, and my friend, who had been to Petra, used to relate with surprise that he found many Romans and also many other strangers residing there. He observed the strangers frequently engaged in litigation, both with one another and with the natives; but the natives had never any dispute amongst themselves, and lived together in perfect harmony.

“XVI.iv.26. The Nabataeans are prudent, and fond of accumulating property. The community fine a person who has diminished his substance, and confer honors on him who has increased it. They have few slaves, and are served for the most part by their relations, or by one another, or each person is his own servant; and this custom extends even to their kings. They eat their meals in companies consisting of thirteen persons. Each party is attended by two musicians. But the king gives many entertainments in great buildings. No one drinks more than eleven cupfuls, from separate cups, each of gold. The king courts popular favor so much, that he is not only his own servant, but sometimes he himself ministers to others. He frequently renders an account before the people, and sometimes an inquiry is made into his mode of life.

“The houses are sumptuous, and of stone. The cities are without walls, on account of the peace which prevails among them. A great part of the country is fertile, and produces everything except oil of olives; the oil of sesame is used instead. The sheep have white fleeces, their oxen are large; but the country produces no horses. Camels are the substitute for horses, and perform the labor. They wear no tunics, but have a girdle about their loins, and walk abroad in sandals. The dress of the kings is the same, but the color is purple.”

Nabateans and Water

The secret to Petra's success was the skill of the Nabateans at flourishing in an extremely arid region with only six inches of rain a year by obtaining, transporting and storing water using a system of cisterns, pools, dams and water channels. The Nabatean water system captured rainwater, channeled streams, prevented floods and utilized spring water. Archeologist Maan al-Huneidi told National Geographic, "We were astonished by how sophisticated their ideas were." An engineer said, "Hydrology is the unseen beauty of Petra. Those guys were absolute geniuses."

On the mountainsides around Petra are hundreds, maybe thousands, of dams and almost as many plaster-lined cisterns carved from solid rock. "Miniature canals linked one catchment area to the next, moving water downhill gracefully, sometimes whimsically, in little troughs of sandstone as finely carved as sculpture," Don Belt wrote in National Geographic.

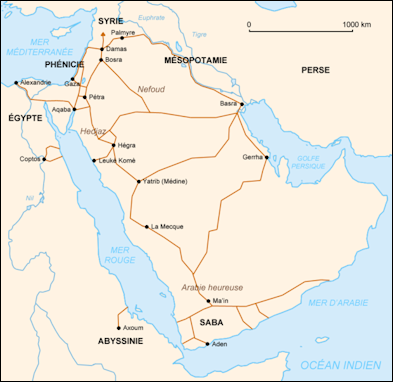

Nabateen trade routes on which frankincense was carried Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Located at the northwest edge of the Arabian Desert, the ancient city of Petra received less than four inches of rain each year. Nonetheless, in its heyday as the capital of the Nabatean Kingdom (first century B.C. to first century A.D.), the city thrived by carefully hoarding this meager rainfall and routing water from several natural springs in the surrounding hills. This required building a system of aqueducts, channels, bridges, and arches, and installing a network of pipelines. The system measured more than 30 miles in all and supplied the city with 35 million gallons of water per year. Petra’s extensive hydraulic infrastructure helped support a population of around 30,000. It also allowed for extravagant displays of conspicuous consumption designed to impress traders and dignitaries who made their way to the city, which was at the crossroads of caravan trade routes connecting Arabia and the Mediterranean. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, March/April 2023

Among the most impressive of these projects was a monumental garden and pool that, since 1998, has been excavated by a team led by archaeologist Leigh-Ann Bedal of Penn State Erie, the Behrend College. On a terrace in the middle of the city that was once thought to have been the site of a marketplace, Bedal’s team uncovered evidence of the pool, which had been hewn from bedrock and measured 150 feet long by 75 feet wide and eight feet deep. In the middle was an island, 33 by 46 feet, outfitted with a pavilion decorated with imported marble and painted stucco. According to Bedal, the island would have been an ideal spot for banqueting or engaging in confidential conversations. “The pavilion had doors on all four sides, so you could see anyone coming,” she says. “You also had the sounds of water falling into the pool from the aqueduct above. So that would have added to the atmosphere and provided additional privacy.” The pool was built during the reign of the Nabatean king Aretas IV (reigned 9 B.C.–A.D. 40) and continued to be used after the Romans annexed Petra in A.D. 106. Within a century, though, the Romans had begun to neglect its upkeep, and the pool started to fill up with soil and debris such as pottery and animal bones.

Nabatean Trade and Caravans

Petra was like a natural fortress near a mountain pass at a crossroads of trade. The Nabateans derived their great wealth and power by levying tolls and sheltering caravans traveling between Egypt, Arabia and Mesopotamia. These caravans carried frankincense and myrrh from Arabia, spices, indigo, and silk from India, and slaves and ivory from Africa.

The Nabateans are believed to have profited greatly from the trade in aromatics, like incense and spices, many of which were used in religious rituals. Two of these were frankincense and myrrh, which many Westerners as the gifts brought to baby Jesus by the Three Wise Men.

Six major caravan roues merged on Petra. The frankincense caravan took 12 weeks to reach Petra from the frankincense groves in Oman. It stopped in Medina, and then made its way across the inhospitable western Arabian desert, where camels and people had to drink brackish water from water holes and the caravans were sometimes attacked by Bedouin raiders. Petra undoubtedly was a welcome sight after all that and a place to get some rest and relaxation.

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: In their prime, the enigmatic Nabateans were key merchants and middlemen connecting the Roman empire to luxury commodities from the east. Roman author Pliny the Elder claimed wealthy citizen-consumers were sending staggering sums of money to Arabia, India, China and each year — an indication of the importance of the trade in coveted goods like silk, incense, and spices. By controlling their passage through the deserts of the Arabian Peninsula, wealthy Nabateans funded a thriving kingdom whose ruins, at sites like Petra in Jordan and Hegra in Saudi Arabia, still stun tourists today. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, August 12, 2023]

Nabateans and the Frankincense Trail

The Nabateans grew rich in part by controlling key choke points of the Frankincense Trail . The Frankincense Trail describes a seaborne and caravan trade route for frankincense and myrrh, linking the places were frankincense was produced in present-day Oman, Yemen, and northern Somalia with markets in the Nile valley, the Fertile Crescent, ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, Rome, and India. [Source: Thomas Abercrombie, National Geographic, October 1985; David Roberts, Smithsonian]

Cultivated from a desert tree that grows in wadis, frankincense is an aromatic gum used in making incense, medicines and as base for amouage perfumes. It was valued by the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans to make incense and fragrances used in burials, sacrifices and important rituals.

Some have suggested that frankincense was the first substance to be traded on a worldwide basis. The Frankincense Trail was the basis for the first civilization to grow up on the Arabian peninsula. The languages of the ancient people along the Frankincense Trail is largely undeciphered.

Frankincense was a fabulous source of wealth to those who grew it and were involved in trading it from 1000 B.C. to A.D. 700. There was a certain mystery as to where it came from as well as stories of terrible things happening to people who tried to find where it came from.

See Separate Article: FRANKINCENSE TRAIL africame.factsanddetails.com

Hegra

Hegra (400 kilometers north of Media in of northwestern Saudi Arabia) is an ancient Nabatean city carved into sandstone and surrounded today by date farms and dusty roads. Also known as al-Hijr or Mada’in Saleh, Hegra is Saudi Arabia’s primary archaeological attractions and was the first place in the country inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list. Built between the first century B.C. and the A.D. first century, this ancient city includes an impressive necropolis, with tombs carved into sandstone set against the sweeping desert landscape. [Source: Lilit Marcus, CNN, January 3, 2024]

According to CNN: Petra was the capital of the Nabatean people, while Hegra was the kingdom’s southern outpost until it was abandoned in the 12th century. The main attraction for tourists are its 115 numbered tombs. The most famous of these is Qasr al-Farid (Arabic for “the lonely castle”) which stands proudly alone, its 72-foot structure dramatically set against an expanse of sand. The contrast makes for an excellent photo backdrop, especially just before sunset as pinkish-orange light sets off the desert tones.

One tomb at a time is open to visitors who want to take a peek inside. These open tombs are rotated through so that no single one gets too much foot traffic. However, they’re much more intricate and interesting on the outside. The area around the door frames can show names of the people buried there. Design details give clues about where the residents may have traveled from. Images of phoenixes, eagles, and snakes imply familiarity with cultures as far away as Greece and Egypt.

Many visitors combine their Hegra trip with visits to the smaller nearby historic sites of Dadan and Jabal Ikmah. In the valley of Jabal Ikmah, which the Saudis refer to as an “open-air library,” you can see a range of carved inscriptions in Aramaic, Dadanitic, Thamudic, Minaic and Nabataean, all of which provide glimmers of insight into the rich history of this region. Translations are shown in Arabic, English, and sometimes French, as French monks were early visitors to the area.Dadan, meanwhile, was once home to a key pre-Islamic trading city, where spice vendors mingled with religious pilgrims. Its most notable site is the “Lion Tombs,” a group of mausoleums decorated with — as the name indicates — carvings of lions.

Hegra — UNESCO World Heritage Site

The Hegra Archaeological Site (al-Hijr / Madā in āli) was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2008. According to UNESCO: it is the largest conserved site of the civilization of the Nabataeans south of Petra in Jordan. It features well-preserved monumental tombs with decorated facades dating from the 1st century BC to the 1st century AD. The site also features some 50 inscriptions of the pre-Nabataean period and some cave drawings. Al-Hijr bears a unique testimony to Nabataean civilization. With its 111 monumental tombs, 94 of which are decorated, and water wells, the site is an outstanding example of the Nabataeans’ architectural accomplishment and hydraulic expertise.

The archaeological site of Al-Hijr’s integrity is remarkable and it is well conserved. It includes a major ensemble of tombs and monuments, whose architecture and decorations are directly cut into the sandstone. It bears witness to the encounter between a variety of decorative and architectural influences (Assyrian, Egyptian, Phoenician, Hellenistic), and the epigraphic presence of several ancient languages (Lihyanite, Thamudic, Nabataean, Greek, Latin). It bears witness to the development of Nabataean agricultural techniques using a large number of artificial wells in rocky ground. The wells are still in use.

The ancient city of Hegra/Al-Hijr is important because: 1) The site of Al-Hijr is located at a meeting point between various civilisations of late Antiquity, on a trade route between the Arabian Peninsula, the Mediterranean world and Asia. It bears outstanding witness to important cultural exchanges in architecture, decoration, language use and the caravan trade. Although the Nabataean city was abandoned during the pre-Islamic period, the route continued to play its international role for caravans and then for the pilgrimage to Mecca, up to its modernisation by the construction of the railway at the start of the 20th century.

2) The site of Al-Hijr bears unique testimony to the Nabataean civilisation, between the 2nd and 3rd centuries BC and the pre-Islamic period, and particularly in the 1st century AD. It is an outstanding illustration of the architectural style specific to the Nabataeans, consisting of monuments directly cut into the rock, and with facades bearing a large number of decorative motifs. The site includes a set of wells, most of which were sunk into the rock, demonstrating the Nabataeans' mastery of hydraulic techniques for agricultural purposes.

Nabatean Trading Outpost in Italy

In 2021, University of Naples archaeologist Michele Stefanile and Michele Silani of Vanvitelli University spotted a slab of white marble in the underwater ruins of the ancient Roman port of Puteoli in Italy’s Bay of Naples. The slab had Latin inscriptions dedicated to a god worshipped 2,000 years ago by the Nabateans. The slab turned out to from a Nabatean temple in the Nabatean’s western-most outpost located on the eastern outskirts of the Roman empire. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, August 12, 2023]

Much of Rome trade’s from the east, a lot of it presumably orchestrated by Nabateans, arrived in Italy via of Puteoli, now located beneath and off the shore of modern Pozzuoli. Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: Founded by Greek colonists in 500 B.C., Puteoli became the most important port of the early Roman empire, and for a few centuries everything from Egyptian grain to Colosseum-bound lions made landfall at Puteoli before moving on to the capital or other parts of the empire.

The newly discovered altar, along with another found close by, prove Nabateans were present in Puteoli as well — but the desert-dwellers weren’t known for their seafaring prowess and had no ports of their own. To find evidence for a Nabatean temple in Puteoli “is really quite bizarre,” says Northwestern University historian Taco Terpstra. “Why on Earth would [Nabateans] set sail themselves, go halfway around the Mediterranean and set up shop in Puteoli? It’s not what they specialize in.”

Stefanile and his colleagues, Vanvitelli University archaeologist Michele Silani and Maria Luisa Tardugno, a researcher working for the Italian heritage authority, say the Nabateans must have been a visible presence in Puteoli. Using drones and laser scans to map the underwater ruins from above, Silani calculated that the newly discovered altars — part of a larger temple — would have been located on prime real estate 2,000 years ago: just 150 feet from the Roman-era shoreline, on one of the two main roads leading up from the beach.

Nabataean trade routes

Nabatean Temple in Italy

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: The temple would have played a critical role for Nabatean merchants far from home who were trying to protect their economic interests and religious beliefs while on foreign soil. “They need a temple to make deals and arrangements under the protection of their gods,” Stefanile says. “This let them conduct ceremonies in the sacred spaces of their homeland.” [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, August 12, 2023]

At the same time, the temple was a sort of billboard to broadcast the presence of Nabatean merchants to potential customers in the busy port, while making a deliberate effort to connect with the local Roman community. “The inscriptions are in Latin, they use Italian marble and Italian construction methods,” Stefanile says.

A marble carving found elsewhere the ruins of Puteoli describes what may have taken place in the Nabatean temple: In A.D. 11, perhaps hoping for divine intervention in their negotiations or a blessing for the risky sea journey home, “Zaidu and Abdelge offered two camels to [the god] Dushara.” Strange as it seems today, there’s no reason to doubt the animal offering was shipped across the Mediterranean for the express purpose of sacrifice: For centuries Puteoli was the main port of entry for lions, ostriches, elephants and other beasts doomed to entertain crowds in Roman arenas, Stefanile points out — so why not a pair of camels?

Terpstra says the Nabatean presence in Puteoli was a combination of listening post and trade promotion bureau. It helped supply newly arrived Nabatean merchants with the local knowledge they’d need to get the best deals, while also reassuring Roman traders that Nabateans were trustworthy partners unlikely to vanish in the night with their coffers. “They’re not there to enjoy the sea breeze, or the view,” Terpstra says. “It must be somehow beneficial for trade.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024