Home | Category: Hittites and Phoenicians

HISTORY OF THE HITTITES

Some believe the Hittites evolved from an Indo-European group that crossed over the Caucasus Mountains into Armenia and Cappadocia. Many historians divide the Hittite era into two periods — the Old or Proto-Hittite Kingdom (1700–1530 B.C.) and the New Kingdom (c. 1420–1200 B.C.). The Hittite Empire reached its peak in the 13th century but collapse not long afterwards. Culturally, the Hittites were adept at assimilating elements of their neighbors. [Source: J. E. Huesman, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Around the second millennia B.C. Indo Europeans tribes from Central Asia and what is now Ukraine invaded Asia Minor. The Hittites, and later the Greeks, Romans, Celts and nearly all Europeans and North Americans descended from these tribes. They carried bronze daggers.

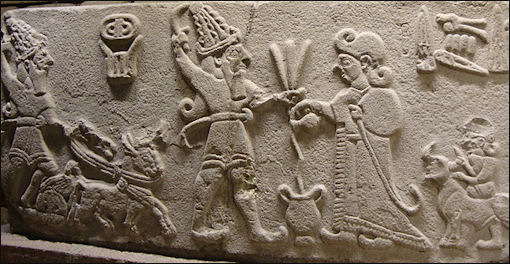

The Hittites were charioteers who wrote manuals on horsemanship. Ninth century B.C. stone reliefs show Hittite warriors in chariots. "Charioteers were the first great aggressors in human history," the historian Jack Keegan wrote. They had an easy time conquering the nomads and farmers that inhabited the region. Donkeys were their fastest animal. See Horsemen.

The Hittites were rivals of ancient Egypt. The were powerful from the 20th to 13th century B.C. and controlled an area that roughly corresponds to modern Turkey and Syria. Around 2000 B.C. the Hittites were unified under a king named Labarna. A later king pushed their domain into Mesopotamia and Syria. The empire lasted into 1650 B.C. A more powerful kingdom rose in 1450 B.C. This kingdom possessed iron.

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Kingdom of the Hittites” by Trevor R. Bryce (Oxford University Press, 1998) Amazon.com;

“The Hittites and Their World” by Billie Jean Collins (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Hittites: Lost Civilizations” by Damien Stone (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Hittites” by Leopold Messerschmidt (1903) Amazon.com;

“Hattusili, the Hittite Prince Who Stole an Empire: Partner and Rival of Ramesses the Great” by Trevor R. Bryce (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Hittites and Their Contemporaries in Asia Minor” by James G. Macqueen (1975) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamian History: Sumerians, Hittites, Akkadian Empire, Assyrian Empire, Babylon” by History Hourly (2021) Amazon.com;

"Life and Society in the Hittite World” by Trevor Bruce (Oxford University Press, 2002).

Amazon.com;

“After 1177 B.C.: The Survival of Civilizations” by Eric H. Cline (2024) Amazon.com;

“I, the Sun” Novel by Janet Morris (1983) Amazon.com;

Arrival of the Indo-Europeans and Hittites in Asia Minor

Indo-European (Aryan) intrusions into Iran and Asia Minor (Anatolia, Turkey) began about 3000 B.C.. The Indo-European tribes originated in the great central Eurasian Plains and spread into the Danube River valley possibly as early as 4500 B.C., where they may have been the destroyers of the Vinca Culture. Iranian tribes entered the plateau which now bears their name in the middle around 2500 B.C. and reached the Zagros Mountains which border Mesopotamia to the east by about 2250 B.C.. The Guti may have been Indo-European.

Hittites and related tribes began entering Anatolia [modern Turkey] from both the northwest (the European Balkans) and the northeast (Russian Georgia) after 3000 B.C.. They conquered and partially absorbed the former residents [the Hatti, from whom the Hittites drew their name]. Small kingdoms were formed and there was some trade with Old Assyria. At some time after 2000 B.C. the separate Hittite kingdoms confederated under the leadership of a king called King, Great King, King of Kings.

This title was common in the ancient world and is frequently translated as emperor. Like many other early Indo-European kingships, the top position was not passed by way of primogeniture; the successor could be any male member of the ruling family. As a result, civil wars frequently determined the succession; and the "Empire" of the Hittites could not maintain a consistent strength because of quarrels over succession. The same is true of related peoples like the Hurrians and the Mitanni. In 1600 B.C. the Hittite Empire was very powerful, but after the successful raid on Babylon in 1590, the Hittites entered a period of weakness.

See Separate Article INDO-EUROPEANS factsanddetails.com

Origin of the Name Hittite

According to the Encyclopaedia Judaica: The name Hittites is taken from the biblical Hebrew itti (gentilic), plural ittim, which stems from the form atti found as a geographic term in cuneiform texts, the vowel change resulting from a Hebrew phonetic law. The form atti is used in Akkadian. Since this name always occurs in combination with a noun, such as "country of atti," "king of atti," etc., it is uncertain whether the final-i is part of the stem or rather the Akkadian genitive ending that would make the nominative attu. [Source: Hans Guterbock; S. Sperling; Ignace Gelb, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

The occurrence of a term attum in Old Assyrian texts (with the-m suffix of the Old Period) had been cited in support of the second alternative. The problem is, however, complicated by the fact that the same sources mention a place called attuš, whose relation to attum is not clear, and that in later periods the Hittites themselves used the form atti for both the country and its capital when they wrote Akkadian, but attuša, also in both usages, when writing Hittite, while an adjective, attili, was derived from the short form. In writing these names the Hittites often used the word sign for "silver," writing silver-ti for Akkadian atti, silver-ša for Hittite attuša. It is worth noting that one of the Ugaritic words for "silver" Ugaritic tt is an Anatolian loanword. Conventionally the form atti is used by moderns.

atti was originally the name of the region comprising the large bend of the river Halys (Kizil Irmak) and of the city whose ruins are at the village of Boghazköy (c. 100 miles directly east of Ankara). The Hittites who ruled that country during most of the second millennium B.C. were invaders speaking an Indo-European language; when they arrived they found a population that spoke a different language, of agglutinative type, and this non-Indo-European tongue they called attili — "belonging to atti." Although both the name Hittite and the term attili are derived from the same geographic name, they refer to entirely different entities. To avoid confusion scholars call the old indigenous language "Hattic" or "Proto-Hattic," the people "Hattians" or "Proto-Hattians," while reserving the term "Hittite" for the Indo-European-speaking newcomers, who took over much of the civilization of the indigenous population in material culture and religion. The reason that Hattic texts have survived at all is that the Hittites still used them in the cult. Thus, there is cultural continuity, the Hattian element being an integral part of the civilization of the Hittites. The Indo-European language called Hittite by moderns was called Nesian by the Hittites themselves, the name being derived from that of Neša, one of their early capitals.

Origin of the Hittites

According to the New Catholic Encyclopedia: Scholars do not agree on the precise area from which the Hittites migrated or the approximate time of their departure. Evidence found in the cuneiform documents of the Assyrian merchant colony at Kültepe reveals numerous Indo-European names. Hence it is clear that the Hittites were established in the area by 1900 B.C., when the Assyrian colony was flourishing. On arrival in Asia Minor they took for themselves the name of an indigenous group, the Hatti, or Hitti.[Source: J. E. Huesman,New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

The history of the Hittite civilization is known mostly from cuneiform texts found in the area of their empire, and from diplomatic and commercial correspondence found in various archives in Egypt and the Middle East. Around 2000 B.C., the region centered in Hattusa, that would later become the core of the Hittite kingdom, was inhabited by people with a distinct culture who spoke a non-Indo-European language. The name "Hattic" is used by Anatolianists to distinguish this language from the Indo-European Hittite language, that appeared on the scene at the beginning of the 2nd millennium B.C. and became the administrative language of the Hittite kingdom over the next six or seven centuries. As noted above, "Hittite" is a modern convention for referring to this language. The native term was Nesili, i.e. "In the language of Nesa". [Source: Crystal Links +/]

According to the Encyclopaedia Judaica: The issue of not knowning when or from where the Indo-European-speaking Hittites came from becomes even more complex if the other Indo-European languages of Anatolia are considered. The documents of the Assyrian merchant colonies give only partial answers to these questions. Among the proper names of local persons there are some that contain Indo-European Hittite elements; accordingly, some individuals, at least, belonging to the newcomers were present in Kaneš in the 19th century B.C. The Hittites derived their own kingdom from the kings of Kuššar, a town, according to Old Assyrian documents recently made available, situated in the mountainous region southeast of Kaneš. [Source: Hans Guterbock; S. Sperling; Ignace Gelb, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Early History of the Hittites

The Hittites were the first-attested bearers of Indo-European names. They were minor players in the 19th and early 18th centuries B.C. , when Hattic princes ruled Anatolia and Assyrian traders dominated the highlands. In the mid 18th century B.C. the Hittites were able to forge a united kingdom out of the remains of the Hattic principalities.[Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

Before the ancestors of the Hittite people arrived in Anatolia (modern Turkey) in the third millennium B.C. The area was already occupied by people known as Hattians and Hurrians who spoke different languages than the Hittites. The Hittites spoke an Indo-European language, the group to which many of the world’s modern languages belong. [Source: Luis Alberto Ruiz, National Geographic, May 1, 2020 =]

The early Hittites borrowed heavily from the pre-existing Hattian culture, and also from that of the Assyrian traders - in particular, the cuneiform writing and the use of cylindrical seals. Since Hattic continued to be used in the Hittite kingdom for religious purposes, and there is substantial continuity between the two cultures, it is not known whether the Hattic speakers - the Hattians - were displaced by the speakers of Hittite, were absorbed by them, or just adopted their language. [Source: Crystal Links]

According to National Geographic History: By the 17th century B.C., the Hittites were emerging as a growing military power under King Labarnas I. His son, Labarnas II, established the capital city at the already established site of Hattusa, changing his name to Hattusilis in honor of the new royal seat. While his father had strengthened the Hittite state, Hattusilis expanded out to the edge of the Mitanni empire, a Hurrian-speaking power to the east. After Hattusilis’ territorial expansion came a contraction and civil wars. As the Hittite princes squabbled over succession, their enemies were able to conquer Hattusilis’ hard-won conquests. =

Sources on the Early History of the Hittites

The early history of the Hittite kingdom is known through tablets that may first have been written in the 17th century B.C. but survived only as copies made in the 14th and 13th centuries B.C.. These tablets, known collectively as the Anitta tex, begin by telling how Pithana the king of Kussara or Kussar (a small city-state yet to be identified by archaeologists) conquered the neighbouring city of Nesa (Kanesh). However, the real subject of these tablets is Pithana's son Anitta, who continued where his father left off and conquered several neighboring cities, including Hattusa and Zalpuwa (Zalpa).” +/

An edict by the 16th-century B.C. king Telepinus standardized Hittite royal succession. The edict contained an account of ancient Hittite kings, a valuable source of information on the Hittites. According to the Encyclopaedia Judaica: Another important source for the early period is the inscription of a certain Anitta, king of Kuššar, found in the Hittite capital and written in Hittite (cos i, 183–85). In it the king relates that his father, Pithana, conquered the city of Neša but spared its people. When he subsequently speaks of his own deeds Anitta mentions Neša as his own city to which he brings captives and booty and where he builds temples. Thus, despite the title King of Kuššar, Neša seems to have been the royal residence. Both Pitḫana and Anitta are attested to in the Assyrian merchant documents found in the later settlement at Kaneš where they apparently ruled. According to some scholars Neša and Kaneš are the same city; this theory, if correct, would greatly contribute to an understanding of the historical situation.[Source: Hans Guterbock; S. Sperling; Ignace Gelb, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Anitta tells about a number of conquests, the most important being that of attuša, which he burned and whose site he cursed. Among the remains of attuša at Boghazköy, documents of the type representative of the later merchant colony were found in houses which had been destroyed by fire, perhaps indicative of the destruction by Anitta. Within the period of the later colony, Pitḫana and Anitta fall relatively late, perhaps in the middle of the 18th century B.C., or even later. Still, knowledge is lacking for the period between Anitta and the beginning of the Old Hittite Kingdom.

Hittite Timeline and King List

Old Hittite Kingdom (1750 - 1500 B.C.) Hattusa becomes the capital

Middle Hittite Kingdom (1500 - 1450 B.C.)

New Hittite Kingdom (Empire) (1450 - 1180 B.C.): Suppiluliumas I conquers Syria; Muwatalli attacks Egyptians (Kadesh)

King of Samal

Old Kingdom

Labarna, ?-1650,

Hattusili I, 1650-1620, grandson

Mursili I, 1620-1590, grandson, adopted son

Hantili I, 1590-1560, brother-in-law

Zidanta I, son-in-law

Ammuna, 1560-1525, son

Huzziya I, brother of Ammuna’s daughter-in-law

Telepinu, 1525-1500, brother-in-law

Alluwamna, son-in-law

Tahurwaili, interloper

Middle Kingdom

Hantili II, 1500-1400, son of Alluwamna

Zidanta II, son

Huzziya II, son

Muwatalli I, interloper

New Kingdom

Tudhaliya I/II, grandson of Huzziya II

Arnuwanda I, 1400-1360, son-in-law, adopted son

Hattusili II , son

Tudhaliya III, 1360-1344, son

Suppiluliuma I, 1344-1322, son

Arnuwanda II, 1322-1321, son

Mursili II, 1321-1295, brother

Muwatilli II, 1295-1272, son

Urhi-Teshub, 1272-1267, son

Hattusili III, 1267-1237, uncle

Tudhaliya IV, 1237-1228, son

Kurunta, 1228-1227, cousin

Tudhaliya IV, 1227-1209, cousin

Arnuwanda III, 1209-1207, son

Suppiluliuma II, 1207-?, brother

[Source: Trevor Bryce, The Kingdom of the Hittites, Oxford, 1998, pp.xiii-xiv. Ancient Near East.net, According to Bryce: “All dates are approximate. When it is impossible to suggest even approximate dates for the individual reigns of two or more kings in sequence, the period covered by the sequence is roughly calculated on the basis of 20 years per reign. While obviously some reigns were longer than this, and some shorter, the averaging out of these reigns probably produces a result with a reasonably small margin of error.”

Important Hittite Kings

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Sometime around 1650 B.C., under Hattushili I, the city of Hattusha was established as the Hittite capital. Situated on a plateau, Hattusha was heavily fortified over time with elaborate defensive walls and gateways. From this secure base, Hattushili led his armies south onto the plains of Syria. His son, Murshili I, continued these advances by raiding the important city of Halab (Aleppo) and plundering Babylon far to the south in Mesopotamia. On his return to Anatolia, however, the king was assassinated and there followed a succession of weak rulers and a long period of inactivity. Around 1420 B.C., a new line of more energetic kings came to power in Hattusha. Nonetheless, the Hittites seem to have suffered considerable problems in the early fourteenth century B.C.: the so-called Gashga people, who lived in the Pontic Alps to the north of Hittite territory, launched raids and may even have destroyed Hattusha; the dominant power of Egypt under Amenhotep III (r. 1390–1352 B.C.) attempted to undermine the Hittites by establishing diplomatic relations with the powerful state of Arzawa in western Anatolia; and raids against Cyprus (claimed by the Hittites as their territory) were undertaken by Ahhiyawa (perhaps Achaean Greeks). [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "The Hittites", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002, metmuseum.org \^/]

Hattusili III

However, under Tudhaliya III (r. 1380–1360 B.C.) and his son Shuppiluliuma I (r. 1370–1330 B.C.), the situation was reversed. Shuppiluliuma consolidated the empire in the north and Hattusha was reconquered and strongly fortified. He then advanced into Syria, establishing Carchemish as a royal center. Egypt now seems to have recognized the Hittites as an equal power: indeed, a later Hittite text refers to an Egyptian queen (perhaps the widow of Tutankhamun) writing to Shuppiluliuma to request marriage with one of his sons. Plague, brought back to Anatolia from the Levant by Hittite soldiers and prisoners of war, cut short the achievements of Shuppiluliuma. However, his conquests were consolidated and expanded by his son Murshili II (r. 1330–1295 B.C.), whose greatest success was against Arzawa in the west, which was reduced to the status of a subject-state.

Under Muwatalli (r. 1295–1282 B.C.), the Hittite capital moved south to Tarhuntasha, perhaps because of the continued threat from the Gashga people. However, control of western Anatolia was maintained and possibly expanded with a treaty agreed between the Hittites and a certain Alaksandu of Wilusa (perhaps Troy). In the Levant, Hittite power was also strengthened when Egypt under Ramesses II attempted to expand beyond the region of Kadesh (Qadesh). Muwatalli's defeat of an Egyptian army led to Hittite control as far south as Damascus. Peace between Egypt and the Hittites was eventually established under Hattushili III (r. 1275–1245 B.C.), prompted perhaps by the growing power of Assyria in northern Mesopotamia.

Under Tudhaliya IV (r. 1245–1215 B.C.), Hattusha was further strengthened and the king completed the construction of a nearby religious sanctuary, known today as Yazilikaya (Turkish: "inscribed rock"). However, during his reign, the empire began to suffer setbacks.

Hittite Old Kingdom

According to the New Catholic Encyclopedia: At first, the new invaders were organized in a loose system of city-states, such as Kusara, Zalpa, and Hattusa. By the 17th century B.C., however, determined efforts at unification resulted in the establishment of a Hittite kingdom. Though credited to Labarna (early 16th century?), this work of unification had its beginnings much earlier. [Source: J. E. Huesman,New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

The first efforts at spreading the Hittite power were pursued by Hattusili, the successor of Labarna, who pushed south into Syria and actually laid siege to Yamkhad (Alep). Not until the advent of Mursili (c. 1535 B.C.) did Aleppo actually fall under Hittite control. This ambitious monarch even swept eastward to sack Babylon in 1530 and put an end to its first dynasty. The destruction of Babylon, however, proved to be simply a passing raid by the Hittites, and Babylonia never became a part of the Hittite Empire.

According to the Encyclopaedia Judaica: Labarna and his successors definitely were Indo-European-speaking Hittites; for Pithana and Anitta this is uncertain but not impossible. If one could reconstruct the course of events so that the Indo-European-speaking Hittites first held the eastern town of Kuššar and from there moved to Neša (= Kaneš?), then to the region of Tyana (Nighde), and finally to atti, it would indicate that the last part of their movement was from East to West, which would favor the eastern route also for their e I fought extensive wars, partly in Anatolia and partly in northern Syria. He boasts of having been the first to cross the Euphrates and of having destroyed Alalakh (Tell Atchana). As his successor attušili appointed an adopted son, Muršili (i), who continued the move toward the southeast by conquering the kingdom of Aleppo and even raiding Babylon, which marks the fall of the First Dynasty of Babylon, dated (in the "middle" chronology) 1595 B.C. This brings Labarna to about 1660.

After the death of Mursili an era of turmoil began, during which succession to the throne usually entailed violence. Simultaneously the Hurrians to the east began to exert pressure on Hittite borders. As a result of these factors, Hittite power retreated into Asia Minor and was unimportant for 100 years.

Rulers of the Hittite Old Kingdom

According to Crystal Links: “The founding of the Hittite Empire is usually attributed to Hattusili I, who conquered the plain south of Hattusa, all the way to the outskirts of Yamkhad (modern-day Aleppo) in Syria. Though it remained for his heir, Mursili I, to conquer that city, Hattusili was clearly influenced by the rich culture he discovered in northern Mesopotamia, and founded a school in his capital to spread the cuneiform style of writing he encountered there.

Some sources say the first Hittite king and founder of the Hittite Old Kingdom was a certain Labarna, alternatively known Tabarna, king of Kuššar, indicating that the kingdom was still connected with that town. It is not clear whether he was really a king though. According to the Encyclopaedia Judaica: That Labarna founded a new dynasty seems likely because of the later tradition which carries historical accounts back to him, but no further; his name was taken by all later kings, so that it almost became a title (comparable to Roman "Caesar"). Labarna's conquests, learned of only from a later source, included Tuwanuwa (near Nighde) and Hupišna (Ereghli). Contemporary sources are for the first time available on his successor, who called himself Labarna (II) and King of Kuššar, but who was better known to posterity by his second name, attušili. This name is the gentilic derived from Hattuša, and, indeed, in his own inscriptions attuša figures as the capital. He moved there, apparently, despite the old curse. [Source: Hans Guterbock; S. Sperling; Ignace Gelb, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

“Mursili continued the conquests of Hattusili, reaching through Mesopotamia and even ransacking Babylon itself in 1595 B.C. (although rather than incorporate Babylonia into Hittite domains, he seems to have instead turned it over to his Kassite allies, who were to rule it for the next four centuries). This lengthy campaign, however, strained the resources of Hatti, and left the capital in a state of near-anarchy. Mursili was assassinated shortly after his return home, and the Hittite Empire was plunged into chaos. The Hurrians, a people living in the mountainous region along the upper Tigris and Euphrates rivers took advantage of the situation to seize Aleppo and the surrounding areas for themselves, as well as the coastal region of Adaniya, renaming it Kizzuwadna (later Cilicia). +/ [Source: Crystal Links +/]

Hittite rule

Muršili was assassinated, and a period of dynastic struggle followed until King Telipinu (c. 1550) introduced strict rules for hereditary succession (cos i: 194–98). Following Mursili the Hittites entered a weak phase of obscure records, insignificant rulers, and reduced area of control. This pattern of expansion under strong kings followed by contraction under lesser ones, was to be repeated over and over again throughout the Hittite Empire's 500-year history, making events during the waning periods difficult to reconstruct with much precision. +/

Telepinu (won a few victories to the southwest, apparently by allying himself with one Hurrian state (Kizzuwadna) against another (Mitanni). His reign marked the end of the "Old Kingdom" and the beginning of the lengthy weak phase known as the "Middle Kingdom", whereof little is known. One innovation that can be credited to these early Hittite rulers is the practice of conducting treaties and alliances with neighboring states; the Hittites were thus among the earliest known pioneers in the art of international politics and diplomacy.” +/

New Kingdom of the Hittite Empire

About 1450 B.C. a new dynasty came to the throne, founding the so-called New Kingdom. According to Crystal Links: “With the reign of Tudhaliya I (who may actually not have been the first of that name; see also Tudhaliya), the Hittite Empire reemerges from the fog of obscurity. During his reign (c. 1400), he again allied with Kizzuwadna, vanquished the Hurrian states of Aleppo and Mitanni, and expanded to the west at the expense of Arzawa (a Luwian state). [Source: Crystal Links +/]

“Another weak phase followed Tudhaliya I, and the Hittites' enemies from all directions were able to advance even to Hattusa and raze it. However, the Empire recovered its former glory under Suppiluliuma I (c. 1350). After Suppiluliuma I, and a very brief reign by his eldest son, another son, Mursili II became king (c. 1330). Having inherited a position of strength in the east, Mursili was able to turn his attention to the west, where he attacked Arzawa and a city known as Millawanda in the coastal land of Ahhiyawa. Many recent scholars have surmised that Millawanda in Ahhiyawa is likely a reference to Miletus and Achaea known to Greek history, though there are a small number who have disputed this connection.

According to the Encyclopaedia Judaica The last king, Suppiluliuma II, tells of a naval victory over ships of Cyprus, but shortly thereafter the Hittite empire is destroyed. The end is marked by burnt levels in all sites and by the disappearance of written sources. However, it is not known how or by whom the destruction was brought about, or what role inner weakness may have played. The only information comes from the Egyptian records of Ramses III, which mention, in his eighth year (c. 1190), the attack of so-called Peoples of the Sea who are said to have overrun all the countries "from atti on." [Source: Hans Guterbock; S. Sperling; Ignace Gelb, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Hittite bas-relief

King Suppiluliuma and His Successors

The Hittite Empire arguably reached its peak under Suppiluliuma I c. 1370–45), who again conquered Aleppo, reduced Mitanni to tribute under his son-in-law, and defeated Carchemish, another Syrian city-state. With his own sons placed over of all of these new conquests, Babylonia still in the hands of the Kassites, and Assyria only newly independent with the crushing of Mitanni, this left Suppiluliuma the supreme power broker outside of Egypt, and it was not long before even that country was seeking an alliance by marriage of another of his sons with the widow of Tutankhamen. Unfortunately, that son was evidently murdered before reaching his destination, and this alliance was never consummated. [Source: Crystal Links]

Luis Alberto Ruiz wrote in National Geographic: In the 15th century B.C., Pharaoh Thutmose III had become Egypt’s great empire builder, extending Egyptian control farther and farther east into Syria. When the Mitanni entered into an alliance with the Egyptians in the early 14th century B.C., the beleaguered Hittite kings grew uneasy at this new relationship. Beset on all sides, the Hittites could have fallen, but a strong ruler raised them up.Suppiluliumas I enjoyed a long reign (1380-1346 B.C.) and helped turn the Hittites into a new imperial force. Exploiting Mitanni weakness, Suppiluliumas conquered northern Syria and installed his sons as kings of Aleppo and Karkemish. Opening with Suppiluliumas’s reign and continuing with his heirs, a three-way power struggle developed with Egypt and the rising power of Assyria to the east. In the decades that followed, the Hittites owed their military successes to their mastery of the war chariot. [Source: Luis Alberto Ruiz, National Geographic, May 1, 2020]

Suppiluliumas was killed by plague, as the existence of the plague poems indicates. His son Mursilis II took the throne, but his reign was overshadowed by pestilence. Although he had to put down constant challenges to his rule, he passed on a stable and expanding empire to his son, who would play a fateful role in Hittite history. The new king was Muwatallis II, who faced Ramses II at Kadesh in 1275 B.C.

According to the Encyclopaedia Judaica Being a younger son, he usurped the throne, but his military and diplomatic success atoned for the usurpation. Having reconquered the lost territories in Anatolia, Suppiluliuma moved against the kingdom of Mitanni in northern Mesopotamia, one of the great powers of the time. After an unsuccessful first attempt, he defeated Mitanni and conquered most of its Syrian territories as far south as Kadesh on the Orontes. At a later date he took advantage of dynastic struggles in Mitanni by helping one of the contenders and installing him as his vassal. In Syria the Hittites also threatened the Egyptian possessions; Hittite sources here supplement the information contained in the *el-Amarna letters. Thus a treaty concluded by Suppiluliuma with Aziru, king of Amurru (cos II, 93–95), shows that the latter actually switched his allegiance from Egypt to atti despite the letters he wrote to the Pharaoh. Most characteristic of the Hittites' prestige is the request of the widow of Tutankhamen, who wrote to Suppiluliuma asking for a Hittite prince whom she would marry and make king of Egypt. The plan failed because her opponents killed the Hittite prince when he arrived, and his father had to send an army to avenge him. [Source: Hans Guterbock; S. Sperling; Ignace Gelb, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Alaca Huyuk “

Suppiluliuma's successors were, on the whole, able to maintain the empire. Muršili II (c. 1345–20) incorporated into the empire as vassals the Arzawa countries of southwestern Anatolia. Muwatalli fought the famous battle of Kadesh (1300 B.C.) against Ramses II of Egypt. Claimed as victory by both sides, the battle left the status of Hittite and Egyptian possession in Syria unchanged. Against the danger stemming from Assyria's rise to power, attušili III concluded a peace treaty with Ramses (1284 B.C.) and later (1271) gave him his daughter as wife. Friendly relations between the two powers continued from that time. Tudhaliya IV (c. 1250) still held Syria, including Amurru; most of his military activity was in the west. During his reign one foreign power, A iyawa, probably the Akhean kingdom of Mycenae and mentioned already by earlier kings, seemed to be aggressive in western Anatolia. Under Tudhaliya's son, Arnuwanda, the situation in the west apparently further deteriorated.

See Separate Article: See Egyptians Under RIVAL KINGDOMS OF THE HITTITE EMPIRE africame.factsanddetails.com

Hittite Kingdom Expands at Egypt’s Expense

According to New Catholic Encyclopedia,: Shortly before 1400 B.C. new vitality began to show itself. Expansionist pressure was directed against northern Syria, but the alliance of Egypt and Mitanni held the Hittites in check. However, when in 1375 the able politician and general Suppiluliuma came to the Hittite throne, a period of decline began for Egypt. Suppiluliuma moved south and took most of Syria and northern Phoenicia from Egypt. When the weak and vacillating Egyptians failed to help Mitanni, it too fell to the Hittites as a vassal state. On the international scene, the fall of Mitanni was the prelude to the resurgence of Assyria under Ashur-uballit. I (1354–1318).[Source: J. E. Huesman,New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

So weak had Egypt become that the young widow of Tutankhamun petitioned Suppiluliuma for one of his sons as her consort in an effort to provide some stability after the chaos of the Amarna Age (see egypt). However, the young Hittite prince was murdered by the Egyptians. War was averted for a time by a plague that was ravaging Hittite lands, but open conflict came when the 19th Egyptian dynasty tried to restore Egyptian control over Syria.

In 1286 Ramses II (1290–1224) led his forces against those of Muwattili (1306–1282) at Kadesh on the Orontes. Although Egyptian hieroglyphs tell of the brilliant victory of the pharaoh, Hittite reports of a savage slaughter of the Egyptian troops are closer to the truth. Confirmation of the Hittite account is the fact that Egyptian forces never ventured into Syria again, though the fighting south of Syria dragged on for another 15 years. It was only the rise of a new menace to the East, Assyria, that led the Egyptians and the Hittites to make peace. In 1270, then, Ramses II and the new Hittite monarch Hattusili III made a treaty that was sealed by the marriage of a daughter of Hattusili to Ramses.

See Separate Article: RIVAL KINGDOMS OF THE HITTITE EMPIRE africame.factsanddetails.com

Fall of the Hittite Kingdom

From its position as a great world power, the Hittite Empire quickly collapsed before the 13th-century as an influx of Aegean peoples migrated into western Asia Minor. Many historians say the responsibility for this collapse lies mainly with the "Sea Peoples," who almost conquered Egypt and eventually settled the coastal plain of Palestine. [Source: J. E. Huesman,New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Hattusa reconstructed wall According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “ Under Tudhaliya IV (r. 1245–1215 B.C.), Hattusha was further strengthened and the king completed the construction of a nearby religious sanctuary. However, during his reign, the empire began to suffer setbacks. The Assyrians launched attacks against the eastern borders of the empire as well as in Syria, reducing Hittite territory in these regions. At the same time, Hittite dependencies in the west were being lost.

Sometime around 1200 B.C., Hattusha was violently destroyed and never recovered. Who destroyed the capital is unknown but it was apparently part of the wider collapse of Hittite power. The reasons for the rapid disappearance of the Hittites, who had dominated Anatolia for centuries, remain unexplained. However, Hittite traditions were maintained in northern Syria by a number of dynasties established under the empire, such as at Carchemish, which continued to flourish through the early centuries of the first millennium B.C. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "The Hittites", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002, metmuseum.org \^/]

See Separate Article: FALL OF THE HITTITE EMPIRE africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, Anatolian Civilizations Museum in Ankara

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024