Home | Category: Late Dynasties, Persians, Nubians, Ptolemies, Cleopatra, Greeks and Romans

PERSIAN RULE OF ANCIENT EGYPT

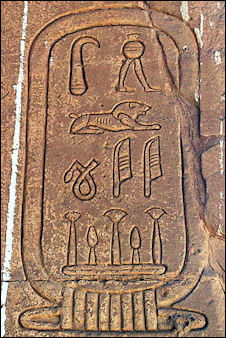

Egyptian cartouche for

the Persian ruler Darius II Egypt was conquered the Persians in 525 B.C. After experiencing a brief period of autonomy it was conquered again by the Persians around. 300 B.C. Egypt remained in Persian hands until they were defeated by Alexander the Great in 332 B.C., at which time Egypt fell under Greek control.

A weak Egypt was no match for Persia at the height of its power. After being conquered by the Persian king Cambyses, Egypt became a backwater province in a large empire. After five Persian rulers, the Egyptian retained control for 10 rulers until the Persian regained control. Among other things the Persians were known for being religiously tolerate and accommodating to the Jews in Egypt.

Cambyses established himself as pharaoh and appears to have made some attempts to identify his regime with the Egyptian religious hierarchy. Egypt became a Persian province serving chiefly as a source of revenue for the far-flung Persian (Achaemenid) Empire. From Cambyses to Darius II in the years 525 to 404 B.C., the Persian emperors are counted as the Twentyseventh Dynasty. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

Egyptian art from the Persian period includes a headless but still impressive stone statue of Ptahhotep, an Egyptian treasury official, dressed in Persian costume with a Persian bracelet but an Egyptian chest ornament. The sculpture, about one-quarter life size and probably from Memphis, illustrates the accommodating mix of Persian and Egyptian costumes during the period of Egypt's rule by Persian kings.

The Late Period (715 to 332 B.C.) included the second part of the 25th dynasty, and 26th, 27th, 28th, 29th, 30th and 31st dynasties and one period of Nubia rule and two periods of Persian rule. The 25th dynasty was Nubian. The 27th and 31st dynasties were Persian. After the 27th dynasty the Persians were expelled but returned once again. By some reckonings the Late period began when Egypt was conquered by the Persians in the 525 B.C. After experiencing a brief period of autonomy Egypt was conquered again by Alexander the Great in 332 B.C.

Scholars generally divide the Persian Period in Egypt into two separate eras, the First Persian Period (Dynasty 27, 525-402 B.C.) and the brief Second Persian Period that ended with the arrival of Alexander the Great (Dynasty 31, 343-332 B.C.). To distinguish from other stages of Iranian history, this era is also called Achaemenid, named after the eponymous founder of the dynasty, Achaemenes. In both periods, Egypt was governed by a Persian satrap. [Source: David Klotz, New York University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BCE”

by Matt Waters (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period”

by Amélie Kuhrt (2007) Amazon.com;

“Persians: The Age of the Great Kings” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones Amazon.com;

“Egypt Under the Saïtes, Persians, and Ptolemies” (Classic Reprint) by E. A. Wallis Budge Amazon.com;

“Primary Sources, Historical Collections: Egypt Under the Saïtes, Persians, and Ptolemies”

by Budge Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis (2023) Amazon.com;

“Afterglow of Empire: Egypt from the Fall of the New Kingdom to the Saite Renaissance”

by Aidan Dodson (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Late New Kingdom in Egypt (c. 1300–664 BC) A Genealogical and Chronological Investigation (Oxbow Classics in Egyptology) by M. L. Bierbrier (2024) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greco-Roman and Late Antique Egypt” by Katelijn Vandorpe (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“A History of Ancient Egypt” by Marc Van De Mieroop (2011, 2021) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: A History from Beginning to End” by History Hourly (2017) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization” by Barry Kemp (1989, 2018) Amazon.com;

Twenty Seventh Dynasty (525 – 404 B.C.): First Persian Period

Horus image from the 27th dynasty

Dynasty 27, First Persian Period, Rulers (525–404 B.C.)

Cambyses (525–522 B.C.)

Darius I (521–486 B.C.)

Xerxes I (486–466 B.C.)

Artaxerxes I (465–424 B.C.)

Darius II (424–404 B.C.)

The 27th Dynasty and the First Persian Period of Egypt began in 525 B.C. when the Persian king Cambyses II conquered Egypt with a victory at the Battle of Pelusium in the Nile Delta, followed by the capture of Heliopolis and Memphis. The Persians received assistance from Polycrates of Samos, a Greek ally of Egypt, and the Arabs, who provided water for his army to cross the Sinai Desert. After these defeats Egyptian resistance collapsed. In 518 B.C. Darius I visited Egypt, which he listed as a rebel country, perhaps because of the insubordination of its governor Aryandes whom he put to death. Persian rulers of Egypt during the 27th Dynasty who were also the rulers of the Persian Empire were: Cambyses 525-522 B.C.; Darius I 522-486 B.C.; Xerxes 486-465 B.C.; ArtaxerxesI 465-424 B.C.; Darius II 424-405 B.C.; Artaxerxes II 405-359 B.C.; [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

James Allen and Marsha Hill of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Egypt's new Persian overlords adopted the traditional title of pharaoh, but unlike the Libyans and Nubians, they ruled as foreigners rather than Egyptians. For the first time in its 2,500-year history as a nation, Egypt was no longer independent. Though recognized as an Egyptian dynasty, Dynasty 27, the Persians ruled through a resident governor, called a satrap, helped by local native chiefs. Persian domination actually benefited Egypt under Darius I (521–486 B.C.), who built temples and public works, reformed the legal system, and strengthened the economy. The military defeat of Persia by the Greeks at Marathon in 490 B.C., however, inspired resistance in Egypt; and for nearly a century thereafter, Persian control was challenged by a series of local Egyptian kings, primarily in the Delta. [Source: James Allen and Marsha Hill, Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

Cambyses II: the Persian Conqueror of Egypt

Cambyses II, son of Cyrus and Cassadane, was born in 558 B.C. and came to the throne during a major rebellion. He moved swiftly to put down the uprisings only to find that his brother, Smerdis, was a primary instigator behind it. In Persian, it was a tradition for the younger sibling to attempt a coup and usurp the throne of the elder brother. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato]

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: After the death of Cyrus, Cambyses inherited his throne. He was the son of Cyrus and of Cassandane, the daughter of Pharnaspes, for whom Cyrus mourned deeply when she died before him, and had all his subjects mourn also. Cambyses was the son of this woman and of Cyrus. He considered the Ionians and Aeolians slaves inherited from his father, and prepared an expedition against Egypt, taking with him some of these Greek subjects besides others whom he ruled. . [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

Cambyses II once reportedly remarked to his mother that when he became a man, he would turn all of Egypt upside down. After eliminating his brother, he was now free to organize a long-anticipated expedition to bring the riches of Egypt into the Hittite Empire. And the time was ripe after Egypt weakened its military with two disastrous campaigns into Syria and Babylon by the unpopular pharaoh, Hophra. There was also a power struggle between Hophra’s regime and the supporters of Amassis, a popular military commander. This struggle ended in Hophra’s untimely demise. Amassis knew the danger that Cambyses II posed and looked to the Greeks for help, which proved fruitless. In fact, Polycrates of Samos actually offered his aid to the Hittites. +\

See Separate Article: PERSIAN CONQUEST AND EARLY RULE OF ANCIENT EGYPT: CAMBYSES II AND UDJAHORRESNET africame.factsanddetails.com

Darius I and Egypt

Darius I is regarded as the noblest and judicial of the Persians to rule Egypt. He tried to make his rule acceptable to the people and clergy and showed an interest in developing Egypt’s economy, trade networks and government institutions. He forged an empire by bringing talented people from all over the empire to places where they were needed. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

David Klotz of New York University wrote: “Cambyses left Egypt in 522 B.C. and died en route to Persia. His brother, Bardiya/Smerdis — or the impostor Gaumata — succeeded him briefly until Darius led a coup and assassinated him in the same year. Darius assumed the throne, reorganized the Empire, and spent much of his time stamping out regional uprisings, including one in Egypt. Recently discovered temple inscriptions from Amheida (Dakhla Oasis) reveal the extent of his rebellion. Furthermore, Aryandes, the first Egyptian satrap, may have tried to break away from the Empire; Darius had him executed for introducing his own coinage; a different tradition maintains that Egyptians revolted against Aryandes and his oppressive policies. [Source: David Klotz, New York University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “Darius I is probably best known for his efforts to truly understand the internal affairs and administration of Egypt. He executed Satrap (Aryandes) for overstepping his office, built a temple at Khargah Oasis and repaired other temples as far apart as Busiris in the Delta and at el-Kab just north of Aswan. Darius I also completed the canal begun by Necho II in 490 B.C., which started in the eastern Delta at Pelusium and ended in the Red Sea (In 490, Necho II had been defeated by the Greeks at the battle of Marathon.). Darius I's attentions eventually went from bureaucracy to other things and in 486 B.C. the Egyptians took the opportunity to revolt. Darius, unable to suppress the uprisings, died and was buried in a great rock-carved tomb in the Cliffs of Persepolis.” +\

Darius I’s Rule of Egypt

Darius as a Pharoah

Egyptian images of Darius I showed him dressed in the style of the old Egyptian kings. He went by the name Ra-SETTU (king of the South and North). According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: He placed his name Darius into hieroglyphic characters within a cartouche as "son of the Sun". Darius has founded a college for the education of the priests. His goal was to erase the negative impressions the Egyptians had of the Persians, including that of Cambyses. His greatest work was the completion of the digging of the canal to join the Nile and Red Sea, which had begun by Necho II. He became acquainted with Egyptian theology and the writings in books. At one point he gained the title of god, which no other Persian king had done. Darius repaired architectural works, but his greatest attempt was the building of the temple in Oasis Al-Kharga in honor of the god Amen. Darius ruled for thirty-six years. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

David Klotz of New York University wrote: “Darius certainly took an active interest in the administration of the country, and he reportedly codified the laws of Egypt. His most notable accomplishment was the excavation of a canal system at Suez, a feat commemorated by several enormous stelae inscribed in both hieroglyphs and cuneiform. According to the Egyptian versions, Darius consulted with Egyptian officials in his palace at Susa and ordered them to excavate a canal in the Bitter Lakes region. After its completion, numerous cargo ships set sail in the Red Sea, circumnavigated the Arabian Peninsula, reportedly in cooperation with the Sabaeans of Southern Arabia, and ultimately arrived in Persia. [Source: David Klotz, New York University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

“This maritime route was preferable to the arduous land journey. Statues and other large stone objects likely took a similar course from the Wadi Hammamat to Persia via the Red Sea , as well as the thousands of Egyptian workmen shipped to Persepolis, Susa, and other building sites. A Persian Period Demotic papyrus from Saqqara mentions the toponym “Twmrk”, perhaps to be identified with the coastal city of Tamukkan near the Persian Gulf, frequently mentioned in Persepolis Fortification Tablets in connection with Egyptian laborers.

“It is uncertain whether Darius ever visited Egypt, or if he mainly corresponded with the satrap and conferred with Egyptian officials residing in Susa and Persepolis. Nonetheless, there is no reason to assume the Great King was somehow oblivious to the Suez Canal excavation or the various temple construction projects going on throughout Egypt, as these enterprises must have required significant resources, manpower, and organization. The Pherendates correspon- dence reveals how closely the satrap micro- managed seemingly trivial questions involving sacerdotal appointments at Elephantine during this reign.”

Darius I’s Building Campaign

Persian tomb in Egypt

David Klotz of New York University wrote: ““In dedicatory texts from Susa, Darius I boasted of assembling an international crew of skilled artisans to construct his palaces. While Babylonians were charged with clearing rubble and making bricks, Egyptian recruits worked the gold, wood, and decorated the walls. Egyptian style is evident in Achaemenid architecture and reliefs, although the cosmopolitan iconographic program interwove artistic traditions from across the Persian Empire. As mentioned above, numerous administrative tablets from Iran record the movements of these Egyptian workers; an Elamite tablet even mentions rations delivered to a local “scribe of the Egyptians, Harkipi”. Egyptian artifacts were discovered at Susa and Persepolis, including amulets, scarabs, and even a Horus “cippus”; various administrative seals from Iran bear short hieroglyphic texts, and numerous stone vessels feature Egyptian cartouches of Persian kings. Artisans and laborers were not the only Egyptians imported to Persia. Cyrus reputedly employed an Egyptian doctor, and Udjahorresnet advised Darius within “Elam,” most likely at the royal court at Susa. [Source: David Klotz, New York University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

“The mass transport of skilled artisans and advisors to Persia may have led to a minor “brain drain” in Egypt. Compared to the Saite Period, temple inscriptions, as well as private stelae and statues, became relatively scarce and of lesser quality. Yet unlike Cambyses, Darius I devoted significant resources to Egyptian temples, earning a positive reputation for religious tolerance . Darius reportedly studied Egyptian theology along with priests, and when he ordered Udjahorresnet to restore the House of Life in Sais, it was because the king “knew the efficacy of the craft of healing the sick, of establishing the name of every god, their temples, their offerings, and conducting their festivals”. As mentioned above, Darius renewed Amasis’s donations of temple lands, and he earned the unique Golden Horus name: “beloved of all the gods and goddesses of Egypt”.

“Although there is only limited evidence for temple construction within the Nile Valley, with fragmentary reliefs from Karnak, Busiris, and Elkab, this phenomenon may result from post-Persian damnatio memoriae . In Kharga Oasis, Darius I rebuilt the large temple of Hibis, and the smaller sanctuary at Qasr el-Ghueita. In Dakhla Oasis, blocks with similar decoration, almost certainly attributable to Darius I, were reused in the Roman Period temple of Thoth at Amheida. Nonetheless, assorted votive objects from his reign have been found across Egypt, including faience and bronze objects from Karnak and Dendera, as well as decor ated naoi at Tuna el-Gebel and an unspecified temple of Anubis and Isis , most likely Cynopolis in Upper Egypt At Memphis, three Apis bulls were interred in regnal years 4, 31, and 34. If the burial ceremony under Cambyses had been a modest affair, the first embalming ritual for Darius was celebrated with much fanfare under the direction of the General Amasis, who aimed to create respect for the Apis “in the heart of all people and all foreigners who were in Egypt”. He sent messengers across Egypt summoning all local governors to bring tribute to Memphis and perform a lavish burial. Around the same time, the Treasurer and Chief of Works under Darius I, Ptahhotep, took credit for “guarding over the temples” of Memphis, multiplying offerings, increasing the clergy, and “reintroducing sacred images, putting all writings (back) in their proper place” . Cambyses had mocked the divine effigy of Ptah in Memphis, but Darius wished to erect his own statue before the same temple (Herodotus II, 110; III, 37).”

Xerxes and Ancient Egypt

Xerxes succeeded Darius I about B.C. 486 or 485. His first important act was the suppression of an Egyptian revolt his father was preparing to crush at the time of his death. Xerxes put down the revolt with great severity. Like Darius, Xerxes had to contend with the Greeks, this time at sea, at Salamis in 480 B.C. He appointed his brother Akhaemenes to govern Egypt and but for the most part neglected it, leaving in worse shape than it was under Darius. Xerxes didn’t do anything for the Egyptian temples. Some say that he may have even robbed them of their treasures. There aren't many monuments attributed to Xerxes either. He was said to be a tall, handsome man yet very cruel and tyrannical. Xerxes was murdered by Artabanus and Spamitres about B.C. 465. He ruled for twenty years and was succeeded by his son Artaxerxes. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Xerxes

David Klotz of New York University wrote: “Shortly after the Persian defeat at Marathon in 490 B.C., and the death of Darius I in 486, Egypt seized the chance to revolt again. Documents from this time mention a native Egyptian king named Psammetichus IV, instead of Darius I or Xerxes. Yet the new king Xerxes quickly regained control, installed his brother Achaemenes as satrap, ended the benefactions granted by Darius, and placed higher demands on the Egyptian population, most likely to fund his massive yet ill-fated campaign against Greece. [Source: David Klotz, New York University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

“No evidence survives for Egyptian temple construction, and the usually copious records for the Apis bulls at Memphis suddenly fall silent precisely during this reign, only resuming about a century later in Dynasty 29. A single posthumous record may allude to a Mother of Apis buried under Artaxerxes I, but the text is very fragmentary. A previous suggestion to identify one Apis from the reign of Darius II has beenretracted.

“According to the Satrap Stela of Ptolemy I, Xerxes confiscated temple lands in Buto, and was duly punished by Horus for this impiety. Despite the clear hieroglyphic spelling of his name, some scholars still identify the Persian king mentioned on the Satrap Stela as (Arta)xerxes III. Among other problems, this theory assumes the Egyptians had already forgotten the name of the Achaemenid ruler who so brutally invaded their country only thirty years before the composition of the Ptolemaic decree. Xerxes famously railed against all gods besides Ahura Mazda in the so-called “Daiva- inscription”, so it is possible that decreased temple revenues in Egypt, as well as the reorganized sacerdotal administration in Babylon, may have had both financial and ideological motivations.

“After this point, traditional historical sources such as biographical or royal inscriptions disappear from the epigraphic record. For most Egyptians, life continued more or less as usual, at least according to administrative records. In sharp contrast to Darius I, subsequent kings no longer bothered with benefactions to Egyptian monuments. Darius II did allow Edfu’s clergy to retain some of its agricultural holdings, but the decoration phase of Hibis Temple sometimes attributed to his reign is not supported by the epigraphic evidence. The minor differences in Darius’s prenomens at Hibis Temple signify little, since such forms varied throughout Pharaonic history.

“Xerxes failed in his Greek campaign, most famously at the battle of Thermopylae (480 B.C.). He was subsequently murdered (464), his eldest sons killed in the ensuing dynastic struggle, until Artaxerxes I eventually took the throne. Around this time, Inaros, an ethnically Libyan chief with an Egyptian name, emerged from the Western Delta and led a revolt in league with Athens. Inaros successfully took Memphis and controlled at least part of Egypt for a full decade. Although some documents from Elephantine refer to Artaxerxes in 460 B.C., a Demotic ostracon from Ain Manawir is dated to regnal year 2 of “Inaros [without cartouche], Chief of the Rebels” or “Chief of the Bakaloi (Libyans)”. Artaxerxes I sent repeated expeditions to recapture Egypt and eventually regained power in 454 B.C., famously destroying the Athenian fleet and crucifying Inaros in the process.

“From the reign of Darius II (423-405 B.C.) are preserved the multilingual archives of the satrap Arsames, offering valuable insight into the administration of Egypt at the end of Dynasty 27. Notably, Egyptian priests of Khnum reportedly destroyed a Jewish temple of Yahwe at Elephantine in 410 B.C., with the approval of the Persian governor Vidranga.”

Artaxerxes II and Ancient Egypt

Artaxerxes became king the Persian Empire after many struggles following Xerxes’s death. He even ordered the death of his brother Darius for their fathers’ murder on the advise of Artabanus, who is believed to have had a hand in Xerxes assassination and wanted one of his own sons to be king of Persia. Artaxerses name isn’t found in Egypt. He adopted the title "Pharaoh the Great", but didn’t adopt a throne name. Artaxeres was opposed by the princes Inaros of Heliopolis and Amyrtaeus of Sais. Despite initial successes with the aid of Greek allies, the Egyptians were defeated and Inaros was executed in 454 B.C. Relative tranquillity ensued after that but otherwise Artaxerxes’s reign left little mark on Egypt. Artaxeres didn’t build, repair or add anything to Egypt. He reigned for forty years and didn’t leave much behind except for a few words on the Stele of Alexander II. +\

David Klotz of New York University wrote: “At the end of the fifth century, another dynastic war erupted in Persia, this time between Artaxerxes II and his younger brother Cyrus. Once again, an Egyptian rebel from the Western Delta, Amyrtaeus (Amenirdis), also called Psammetichus V, expelled the Persians from Memphis around 405 B.C., employing mercenaries from Crete; the full revolution may have taken several years to complete. The only king of Dynasty 28, Amyrtaeus is briefly mentioned by Manetho and Diodorus Siculus (XIV, 35), and confirmed by a few documentary texts. After a few years, he was overthrown by Nepherites I, founder of the Mendesian Dynasty 29, thus ushering in the Late Dynastic Period. [Source: David Klotz, New York University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

Egypt Under Persian Rule

David Klotz of New York University wrote: Like the period of Hyksos rule in the Second Intermediate Period, the Persian Dominations inflicted perpetual trauma upon the cultural memory of Egypt. For several centuries, Egyptians continued to blame Cambyses for disfiguring or robbing Egyptian monuments such as the Colossus of Memnon, and other Persian kings were reputed to have committed equally blasphemous deeds against Egyptian gods. In Demotic literature from the Roman Period, Assyrians are blamed for stealing the divine images, although some texts anachronistically conflate Assyrians and Achaemenid Persians. An echo may even be found in the Bentresh Stela , in which the ruler of a distant country, Bakhtan, refuses to return the cult statue of Chonsu-pA-jr-sxrw to Egypt. [Source: David Klotz, New York University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

Egyptian man in Persian clothes

“This reputation may have some basis in reality. The first few Ptolemies repeatedly claimed to have recovered lost Egyptian divine statues in Syro-Palestine, supposedly stolen by the Persians. These sources are often dismissed as a mere anti-Persian topos or Ptolemaic propaganda, but surprisingly detailed accounts of such discoveries are recounted in the Pithom Stela of Ptolemy II and the recently discovered decree of Ptolemy III from Akhmim. Moreover, certain 30th Dynasty texts refer to such temple destruction prior to the invasion by Artaxerxes III, and the systematic “damnatio memoriae “against Amasis’s monuments can only be attributed to Cambyses. Archaeological evidence in some cases is inconclusive, but various evidence suggests major disruptions, if not destruction, precisely in the late sixth century B.C.

“While the Ptolemies later emphasized the impieties and abuses of their predecessors, the Persian Period was not all repression and exploitation, and in fact there is evidence for acculturation and international contact during this era. Egyptian elite officials donned Persian garments and jewelry, just as indigenous officials later wore the Hellenizing “mitra “on their statues in the late Ptolemaic Period; in this way privileged native officials distinguished themselves as what Pierre Briant dubbed the “ethno-classe dominante”. Meanwhile, Persian dignitaries composed hieroglyphic dedications for Egyptian deities in the Wadi Hammamat. Religious

syncretism is evident on the Suez Canal stelae, where the Egyptian winged sun disk on one side is replaced by the Zoroastrian winged figure on the reverse; Atum, the original Egyptian creator god, was sometimes likened to Ahura Mazda. Kákosy suggested fire became more important in Late Period Egyptian religion and magic resulting from Zoroastrian influences at this time, but this natural element was important in all periods.

“This hybrid style is most apparent with Darius’s statue from Susa, although it is uncertain if it ever stood in Egypt. The hieroglyphic inscription mentions that Darius commissioned the effigy “so his name might be commemorated beside Atum, Lord of the Lands of Heliopolis, and Ra-Horakhty”, suggesting it was originally erected in a temple of Atum in Heliopolis or Pithom, near the Red Sea canal, but for some reason taken back to Persia and installed in the palace of Darius I at Susa. However, Atum and Ra- Horakhty may simply represent the closest Egyptian equivalents to Ahura Mazda, the god mentioned in the statue’s Cuneiform texts. As a similar example of an Egyptian monument commissioned abroad, one may compare the obelisk of Domitian now in Benevento; although erected in Rome, the hieroglyphic inscriptions dedicate that monument to Ra- Horakhty.

“Several Achaemenid-style royal heads with full, curly beards have been discovered in Egypt, but Darius I is depicted in traditional Egyptian poses at Hibis and Ghueita. Curiously, similar images of the bearded Egyptian god Bes were popular throughout the Achaemenid Empire, notably on the widespread theomorphic “Bes jars”.

“While Persian cultural influence may not have been great, this period witnessed intensified interactions with Greek states, especially Athens, culminating in the Athenian support of the rebel Inaros, and continued military and political alliances during Dynasties 29-30. Indeed, the increasing Hellenization of the Delta is confirmed in its material culture, which shows a wide diffusion of Aegean imports, but few properly Iranian forms. Notably, the earliest coin in Egypt, the “Ionian stater,” is first mentioned in a Demotic text from the reign of Artaxerxes I (412-411 B.C.).

“The Persian Period also introduced Egypt to foreign domination, being occupied by alien soldiers and administered in a new language (Aramaic), and thus presented valuable lessons for the subsequent Ptolemaic Dynasty. For example, most native Egyptian revolts against the Persians originated in the Western Delta, and this is precisely where the early Ptolemies concentrated their administration in Alexandria, while they offered numerous benefactions to Lower Egyptian temples and cities. Throughout the Ptolemaic Period (304–30 B.C.), enemies were often designated as “Medes”, while soldiers and low- status Greeks, who nonetheless enjoyed more privileges than common Egyptians, were mysteriously called “Medes” or “Persians” in administrative texts. Finally, the renewed settlements in the Western Oases (made possible in part through the introduction of Persian “qanat “technology; cf. Briant 2001, and frequent expeditions into the Eastern Desert and the Red Sea, led directly to to the heavy exploitation of both regions under Greek and Roman rule.”

Periodic Egyptian revolts, usually aided by Greek military forces, were unsuccessful until 404 B.C., when Egypt regained an uneasy independence under the short-lived, native Twenty-eighth, Twenty-ninth, and Thirtieth dynasties. Independence was lost again in 343 B.C., and Persian rule was oppressively reinstated and continued until 335 B.C., in what is sometimes called the Thirty-first Dynasty or second Persian occupation of Egypt. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

Temples in the 27th Dynasty

Christiane Zivie-Coche wrote: In spite of the Greek historians’ traditionally anti-Persian sentiment underscoring the aggressive manipulations of the Achaemenids in Egypt, the kings of the 27th Dynasty (the First Persian Period) apparently did not pillage or destroy the Egyptian temples, nor did they kill the sacred Apis bull, a sacrilegious crime often attributed to the Persian rulers. Little evidence from this period has survived in the Nile Valley or the Delta, apart from stelae found during the excavation of the Suez Canal. [Source: Christiane Zivie-Coche, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris Sorbonne, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“In contrast, evidence from the Kharga Oasis is extremely well preserved, if not abundant. There, the temple at Hibis remains the only witness to the scope and nature of the building activities during the Late Period, before the start of the Ptolemaic Period. Construction at Hibis may have begun in the 26th Dynasty, but the temple was primarily built during the succeeding (27th) dynasty and decorated mostly by Darius. The temple was completed during the rule of the 30th-Dynasty king Nectanebo II. The construction follows the plan of the traditional Egyptian temple, but underwent a number of modifications.

“The temple at Hibis was dedicated to Amun, “Lord of Hibis.” It contains, on one side, an adaptation of the Theban theology and, on the other, several rooms dedicated to Osiris. The decorative program encompassed notable peculiarities that have not been found elsewhere. The decorated naos has nine registers on its walls, which contain approximately 700 representations of both gods and of what may perhaps be divine statues. At the head of these representations, the king is shown in each register performing a ritual. Grouped by “sepat” (geographic-religious entities) they present an overview of the active cults of the time, organized by region. Interestingly, each “sepat” takes a form of Osiris. In spite of the brevity, or complete absence, of explanatory texts, the richness of these images, many of which are unique, provides an extraordinary glimpse into the theological developments of the Late Period. By comparing these images with the earlier glosses in the mythological Delta Papyrus , or with the later Ptolemaic temple inscriptions, we find a consistent number of cults. Thus the Egyptian pantheon, or at least a large part of it, was brought together on the walls of the cella of the Amun temple at Hibis. The naos was, in effect, conceived of as a microcosmos wherein the gods of Egypt were gathered and the yearly rebirth of Osiris celebrated. This is a very different vision than that provided by Ptolemaic temple-reliefs, wherein the king was portrayed leading a procession of geographic divinities towards the main god of the temple. The latter emphasized the organization of the religious provinces, each “sepat” being listed with their principal god, their town, and the geographical divisions.

“The hypostyle hall of the Hibis temple was also decorated in an unusual fashion. The walls were laid out as an enormous papyrus roll decorated with vignettes and containing a series of hymns to Amun. Several passages of these hymns are known from earlier texts, such as the “magical” Papyrus Harris and the hymn to the ten “bas” of Amun from the Edifice of Taharqa at Karnak, which is one of the first examples of a religious hymn reproduced on a wall painting — a common feature in the later Ptolemaic temples. During the 27th Dynasty a mudbrick temple dedicated to Osiris-“iw” was built in the southern part of the Kharga Oasis. Excavation of this temple (at the site of Ayn Manawir, near Dush) has yielded numerous bronze statues of the god as well as a large quantity of demotic ostraca.

Herodotus on a Fifth Century B.C. Greek Temple in Egypt

Fifth Century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: Hellenic usages they will by no means follow, and to speak generally they follow those of no other men whatever. This rule is observed by most of the Egyptians; but there is a large city named Chemmis in the Theban district near Neapolis, and in this city there is a temple of Perseus the son of Danae which is of a square shape, and round it grow date-palms: the gateway of the temple is built of stone and of very great size, and at the entrance of it stand two great statues of stone. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A.D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

Within this enclosure is a temple-house and in it stands an image of Perseus. These people of Chemmis say that Perseus is wont often to appear in their land and often within the temple, and that a sandal which has been worn by him is found sometimes, being in length two cubits, and whenever this appears all Egypt prospers. This they say, and they do in honour of Perseus after Hellenic fashion thus — they hold an athletic contest, which includes the whole list of games, and they offer in prizes cattle and cloaks and skins.

When I inquired why to them alone Perseus was wont to appear, and wherefore they were separated from all the other Egyptians in that they held an athletic contest, they said that Perseus had been born of their city, for Danaos and Lynkeus were men of Chemmis and had sailed to Hellas, and from them they traced a descent and came down to Perseus: and they told me that he had come to Egypt for the reason which the Greeks also say, namely to bring from Libya the Gorgon's head, and had then visited them also and recognised all his kinsfolk, and they said that he had well learnt the name of Chemmis before he came to Egypt, since he had heard it from his mother, and that they celebrated an athletic contest for him by his own command.

Thirty First Dynasty 343 – 332 B.C.: Brief Second Persian Period

from the 31st Dynasty

The 31st Dynasty, the second Persian Dynasty, was only a decade long. There appears to have been a great deal of internal strife, with both Artaxerxes III and Arses — two Persian leaders —being killed off by their successors. Artaxerxes’ first attempt to conquer Egypt, which had been independent since 404 B.C., ended in failure. He tried again a few years later and defeated Nectanebo II at Pelusium in the Nile delta. The walls of Egypt’s cities were destroyed, its temples were plundered, and Artaxerxes was said to have killed the Apis bull with his own hands. The Persians then proceeded to squander most of Egypt's treasures. The period ended when Alexander the Great claimed Egypt and defeated the Persians. Darius III was the last king of the Persian Empire. Considered by many to be of a good natured weakling, he assumed the throne in 336 B.C. and was assassinated by his own men in 330 B.C. while trying to escape from Alexander the Great. Leaders from the 31st Dynasty were: Artaxerxes III 343-338 B.C.; Arses 338-336 B.C.; and Darius III 336-332 B.C. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

David Klotz of New York University wrote:“Scholars divide the Persian Period in Egypt into two separate eras, the First Domination (Dynasty 27,525-402 B.C.) and the brief Second Domination that ended with the arrival of Alexander the Great (Dynasty 31, 343-332 B.C.). To distinguish from other stages of Iranian history, this era is also called Achaemenid, named after the eponymous founder of the dynasty, Achaemenes. In both periods, Egypt was governed by a Persian satrap. [Source: David Klotz, New York University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

“After almost fifty years of independence, prosperity, and hegemony in the Eastern Mediterranean, Egypt succumbed once again to the invading Persian army of Artaxerxes III in 343 B.C., and the native king Nectanebo II fled to Ethiopia for refuge. The second Persian domination lasted only nine years, finally ending when Alexander the Great captured Heliopolis in 332.

“The Egyptian chronology of this period is further complicated by the mysterious king Khababash. His precise origins remain obscure, and scholars have alternately proposed he might be a Persian official, Libyan rebel, or Ethiopian chief. The latter option may be the most likely, as his name resonates with regional ethnonyms, and he could have allied with Nectanebo II after the latter fled to the south. Little is known of his brief reign, but he buried an Apis bull in Memphis, and the Satrap Stela credits him with restoring temple lands to Buto.”

Persian Rulers of 31st Dynasty: the Second Persian Dynasty

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “After a period of independence for Egypt, Artaxerxes III of Persia conquered Egypt on his 2nd attempt. He had previously tried to conquer Egypt in 351 B.C., but was unsuccessful. In 342 B.C., he succeeded. He was able to dethrone Netanebo II, which ended the 30th Dynasty. Artaxerxes III left no historical records in Egypt, besides coins inscribed with his name in Demotic. Various biographical texts have been dated to this period, but with two major exceptions—Tjaihapimu, son and heir to Nectanebo II, and the Sakhmet priest Somtutefnakht from Herakleopolis. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

When Artaxerxes III took over Egypt, he had the city walls destroyed, started a reign of terror, and set about looting most of the Egyptian treasures, including temple items that were taken back to Persia. Persia gained a significant amount of wealth from this looting. During the rule of Artaxrexes III, sacred animals to the Egyptians were killed, cities were destroyed and the Egyptian people were either taken into slavery or were forced to pay incredibly high taxes. One of his aims was to weaken Egypt enough that it could never revolt against Persia. For the 10 years that Persia controlled Egypt, religion was persecuted, sacred books were stolen, and Egyptians in general were treated very badly. +\

The reign of Artaxerxes III ended when he was poisoned in 338 B.C. after only five years of control over Egypt by one of his previous advisers, the eunuch Bagoas. Artaxerxes III’s son Arses became the ruler of Persia. It is unclear whether Arses had control over Egypt, or a Nubian prince named Khabbash was in control of Egypt during Arses’ reign. Whoever was in charge, Bagoas also removed Arses from power in 335 B.C., and Darius III became the ruler of Persia and Egypt.

“Darius III's control over Egypt was tenuous and short lived. During his four years as ruler, the Persians did little to help him exert control over the Egyptian empire. When Alexander the Great began to move against Egypt in 332 B.C. Darius III allowed him to take it without contest. By turning over control so easily, he saved his own life and was given a high office in Babylon by Alexander as a reward. +\

Dynasty 31: Second Persian Period (343–332 B.C.)

Khabebesh (343–332 B.C.)

Artaxerxes III Ochus (343–338 B.C.)

Arses (338–336 B.C.)

Darius III Codoman (335–332 B.C.)

Temples in the 31st Dynasty

Christiane Zivie-Coche wrote: “After the devastation that took place during the Second Persian Period, Egypt went through a period of major development that included the reconstruction of existing temples and the creation of new religious structures — an ambitious project that was continued and intensified during the Ptolemaic Period. It should be emphasized that, prior to the Second Persian Period, both the temple design and the cults celebrated within had witnessed profound transformations, such as the creation of the “wabet” (the open court dedicated to the celebration of the New Year), the addition of chambers for the cult of Osiris, and the creation of the birth house, or mammisi, where the birth of the child-god was celebrated. The latter was a continuation of a development that had begun in the Third Intermediate Period, in which an emphasis on birth replaced that of the royal-divine marriage. [Source: Christiane Zivie-Coche, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris Sorbonne, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

Khons-the-Child, son of Amun and Mut, is held in high favor, but most often represented is the child-god Horus, in his various forms as Harpocrates “Horus the Infant”; Harsiese “Horus, Son of Isis”; or Harendotes “Horus, the Avenger of his Father.” His reputation has been linked to the Late-Period popularity of Isis and Osiris, which is manifest in the grand Osirian festivals held in the month of “Khoiak” to celebrate the rebirth of the deceased god, and in the establishment of an Iseum in several locations, such as Behbet el-Haggar and Philae. At the same time a complex and subtle theology of Amun was developed at Thebes. Amun himself, worshiped in his temples at Karnak and Luxor, honored, in his form of Amun of Ipet, a mortuary cult performed every 10 days for the deceased ancestor gods buried in the Mount of “Djeme”, located on the west bank, not far from the cemetery area. It is questioned whether the god may have actually visited himself every ten days, or whether “substitution cults” performed the cult in his place.

“It should be noted that the last indigenous dynasties saw the start of the development of enormous animal-necropoli, such as the Anubieion at Saqqara, where tens of thousands of mummified falcons, ibises, cats, and dogs were deposited, and which reflects a practice — different from that of the sacred-Apis cult — that would become especially popular in the Ptolemaic Period.

32nd Dynasty: Alexander the Great in Egypt

Alexander the Great defeated the Persian leader Darius III at Issus in 333 B.C. and then headed towards Egypt, where he was welcomed as liberator. He stayed less than a year, but in that time he was crowned as pharaoh. He founded a harbor town on the northwest coast of the Delta, named Alexandria in his honor. In the division of Alexander's empire after his death in 332 B.C., Egypt was given to his general, Ptolemy, son of Lagus, who established himself as Ptolemy I Soter (305–285), king of Egypt and founder of the house of the Ptolemies.

In November 332 B.C. Alexander entered Egypt, an unhappy vassal of Persia. He received a hero's welcome. In Memphis, the Egyptian capital, he made a sacrifice to Apis, the sacred Egyptian bull, and was recognized as a pharaoh. Hieroglyphics of Alexander's adventures adorn temples in Luxor. He was officially a Pharaoh of the 32nd Dynasty from 332 to 323 B.C.

In 331 B.C., Alexander the Great trekked 300 miles across the Sahara desert for no military reason to Siwa Oasis (near Libyan border), where he met with the oracle at the Zeus-Amum temple and asked questions about his future and divinity. The oracle greeted Alexander as the son of Amun-Re and gave him the favorable omens he wanted for an invasion of Asia. The 24-year-old Alexander arrived at Siwa by camel. He asked the oracle whether was the son of Zeus. He never revealed the answer to that question.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of Alexander's military campaign was the founding of Alexandria. Arrian wrote that "he himself designed the general layout of the new town, indicating the position of the market square, the number of temples...and the precise limits of its outer defenses." After Alexander died, Alexandria grew into the center of Hellenistic Greece and was the greatest city for 300 years in Europe and the Mediterranean.

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “The arrival of the Macedonians marked the end of political autonomy of Egypt. Egypt's new rulers, Alexander and the Ptolemies, tipped the balance of world power firmly towards the west. They preserved the basic framework of Egyptian society, while they operated according to the rules of their own culture. Alexander and the Greeks had the same problem as the Persians, the empire was so extensive that they could not rule the whole entity according to the same set of laws. In order to insinuate the Greeks into Egypt's theocratic method of government, Alexander was obliged to seek the assistance of the very fixture that had supported the pharaohs: the priesthood. Slowly the Greco/Roman culture began to replace the Egyptian cultural milieu. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

See Separate Article: ALEXANDER THE GREAT IN EGYPT AND GAZA europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024