Home | Category: Late Dynasties, Persians, Nubians, Ptolemies, Cleopatra, Greeks and Romans

PERSIAN CONQUEST OF ANCIENT EGYPT

Egypt was conquered the Persians in 525 B.C. After experiencing a brief period of autonomy it was conquered again by the Persians around. 300 B.C. Egypt remained in Persian hands until they were defeated by Alexander the Great in 332 B.C., at which time Egypt fell under Greek control.

A weak Egypt was no match for Persia at the height of its power. After being conquered by the Persian king Cambyses, Egypt became a backwater province in a large empire. After five Persian rulers, the Egyptian retained control for 10 rulers until the Persian regained control. Among other things the Persians were known for being religiously tolerate and accommodating to the Jews in Egypt.

Cambyses established himself as pharaoh and appears to have made some attempts to identify his regime with the Egyptian religious hierarchy. Egypt became a Persian province serving chiefly as a source of revenue for the far-flung Persian (Achaemenid) Empire. From Cambyses to Darius II in the years 525 to 404 B.C., the Persian emperors are counted as the Twentyseventh Dynasty. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

The Persian Empire rose under Cyrus the Great in the sixth century B.C. In 525 B.C., the Persian emperor, Cambyses, pressed west into Egypt and captured King Psamtek III (526–525) at Pelusium in the eastern Delta. Egypt became part of the Persian Empire, run by an appointed official called the satrap; Manetho termed this period Dynasty 27. The emperor, Darius I (522–486), showed some interest in the country, but after his death Egyptian leaders began to wrest power away from Persia. The last three native dynasties (Dynasties 28, 29 and 30), each based in the Delta, attained Egyptian independence and saw a short-lived renaissance of native culture. In 341 B.C., however, Persia reestablished control of Egypt under the emperor Artaxerxes III (358–338), succeeded by Darius III (338–335). [Source: New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003]

See Separate Article: PERSIAN RULE OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BCE”

by Matt Waters (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period”

by Amélie Kuhrt (2007) Amazon.com;

“Persians: The Age of the Great Kings” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones Amazon.com;

“Egypt Under the Saïtes, Persians, and Ptolemies” (Classic Reprint) by E. A. Wallis Budge Amazon.com;

“Primary Sources, Historical Collections: Egypt Under the Saïtes, Persians, and Ptolemies”

by Budge Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis (2023) Amazon.com;

“Afterglow of Empire: Egypt from the Fall of the New Kingdom to the Saite Renaissance”

by Aidan Dodson (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Late New Kingdom in Egypt (c. 1300–664 BC) A Genealogical and Chronological Investigation (Oxbow Classics in Egyptology) by M. L. Bierbrier (2024) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greco-Roman and Late Antique Egypt” by Katelijn Vandorpe (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“A History of Ancient Egypt” by Marc Van De Mieroop (2011, 2021) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: A History from Beginning to End” by History Hourly (2017) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization” by Barry Kemp (1989, 2018) Amazon.com;

Cambyses II: the Persian Conqueror of Egypt

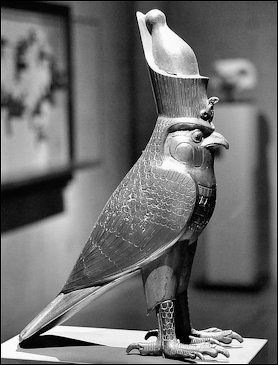

Horus image from the 27th dynasty

Cambyses II, son of Cyrus and Cassadane, was born in 558 B.C. and came to the throne during a major rebellion. He moved swiftly to put down the uprisings only to find that his brother, Smerdis, was a primary instigator behind it. In Persian, it was a tradition for the younger sibling to attempt a coup and usurp the throne of the elder brother. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato]

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: After the death of Cyrus, Cambyses inherited his throne. He was the son of Cyrus and of Cassandane, the daughter of Pharnaspes, for whom Cyrus mourned deeply when she died before him, and had all his subjects mourn also. Cambyses was the son of this woman and of Cyrus. He considered the Ionians and Aeolians slaves inherited from his father, and prepared an expedition against Egypt, taking with him some of these Greek subjects besides others whom he ruled. . [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

Cambyses II once reportedly remarked to his mother that when he became a man, he would turn all of Egypt upside down. After eliminating his brother, he was now free to organize a long-anticipated expedition to bring the riches of Egypt into the Hittite Empire. And the time was ripe after Egypt weakened its military with two disastrous campaigns into Syria and Babylon by the unpopular pharaoh, Hophra. There was also a power struggle between Hophra’s regime and the supporters of Amassis, a popular military commander. This struggle ended in Hophra’s untimely demise. Amassis knew the danger that Cambyses II posed and looked to the Greeks for help, which proved fruitless. In fact, Polycrates of Samos actually offered his aid to the Hittites. +\

Cambyses II’s Campaign Against Egypt

“But now Cambyses II had a logistical problem. He had to march his army across fifty miles of desert. He was in luck. Phane of Halicarnassus, a Greek mercenary in the employ of Amassis, quarreled with his employer and now offered his services to the Hittites. He knew the Sheiks of the desert and arranged for their aid with provisions. Cambyses II was also building a fleet in his Phoenician ports to threaten from the sea. +\

“During this, Egypt was plagued by ill omens. Amassis died shortly before the invasion began, and it rained on the city of Thebes, an event that had been recorded no more than twice in one century. This put his heir, Psammeticus III, in a hard situation. He must defeat a numerically and better equipped enemy with a despairing populace and a country coming apart at the seams. Undeterred, he gathered all the troops he could muster (Greeks, Libyans, Cyrenaeans and Ionians), and set out to face the Hittites at Pelusium. Outnumbered, the Egyptians and their allies were put to flight and a rout began. Rather than finding a defensible position in the swamps of the delta, Psammeticus let Cambyses II pressure him all the way to Memphis and this move from a historical stand point has proved to be a debacle for anyone foolish enough to attempt it. +\

“During one battle, a Persian ambassador sailed up the Nile in a Mitylenean boat, and proposed terms of surrender to the Egyptian rebels in Memphis, Egypt. When the Egyptians saw the boat coming, they attacked it and smashed it to pieces as well as killing all of the crew members. The Persian army moved up to Memphis and forced the rebels to surrender prompting several other groups to offer gifts of tribute to Cambyses II. Ten days later, Cambyses II protested to the royal judges for justice. It was decided that ten Egyptians would die for every Persian who had been killed on the boat. In the end two thousand Egyptians had been executed. Many years after this had occurred, Egypt, like Babylon and Assyria, became a province of the Persian Empire.” +\

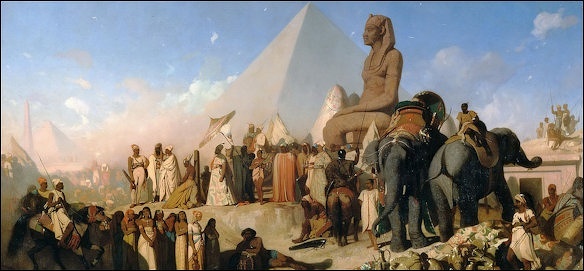

Cambyses's meeting with Psammetichus III

Cambyses II’ Conquest of Egypt

David Klotz of New York University wrote: “Herodotus provides the most coherent account of the Persian invasion of Egypt, a theme elaborated upon much later in the Coptic “Cambyses Romance”, and the Ethiopic “Chronicle “of John Nikiou. Cambyses reputedly attacked Egypt out of anger towards Amasis, who insulted Cyrus by sending Nitêtis, a daughter of Apries and not his own child, to wed the Persian king . Yet his foreign policy was a logical extension of his father’s campaigns, especially since Amasis had pledged Egypt into an alliance with Lydia, Babylon, and Sparta. With the logistical support of Arabian chiefs, Cambyses led his army through northern Sinai, from Gaza to Pelusium . After a short battle, Amasis’s heir, the short-lived Psammetichus III, and his mercenary army retreated to Memphis, only to surrender after a heavy siege. Libya and Cyrenaica quickly followed suit, and preemptively sent tribute to the Persian king. [Source: David Klotz, New York University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

“Cambyses humiliated Psammetichus III before the army in Memphis, and when the latter king refused to accept the Persian authority, he was condemned to death by drinking bull’s blood . Despite his ephemeral reign, Psammetichus III completed a temple to Osiris in Karnak and was posthumously commemorated by Udjahorresnet on his statue, and thus he was more than a “nebulous figure”. The Egyptian campaign began roughly in the winter of 526 B.C., and Cambyses was crowned by the summer of 525 B.C. at the latest.

“Cambyses then advanced with his army to Sais, capital of the preceding 26th Dynasty, where he disinterred the mummy of Amasis and abused his corpse. The posthumous attacks upon Amasis are further evidenced by the systematic erasure of his cartouches on both royal and private monuments throughout Egypt, and possible attacks specifically targeting his temples. While Amasis approved major temple construction projects throughout Egypt, none of his monuments stand today, but survive only as fragmentary blocks. Nonetheless, the “damnatio memoriae “did not last long, as the statue of Udjahorresnet, carved under Darius I, once again mentions Amasis, and his son Henat served in Amasis’s posthumous royal cult.”

Cambyses II as the Ruler of Egypt

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: After reducing Memphis after a short siege, Cambyses took steps to assure a legitimate path to the throne. He adopted the double cartouche of the Pharaohs, the royal costume, and laid claim to be the son of Re. He also embraced Egyptian religion and land usage methods, and had a tutor, Uazahor-resenet, to teach him Egyptian customs. Overall, Cambyses had a profound affect on Egypt, bringing new vigor and quality leadership as well as a genuine interest in the Egyptian way of life. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato +]

During his reign, Cambyses had destroyed several temples at Memphis and became a tyrant in the eyes of his people and court members. Some even thought he was crazy due to the outlandish things he would do such as having twelve Persian nobles buried in the ground up to their neck for reason at all. He had many killed because of comments that upset or offended him. It is said that Cambyses reigned for seven years and five months. In an attempt to rush off on one of his horses, Cambyses was wounded in the thigh when a portion of the scabbard of his sword fell off. He soon died from the effects of the wound, which caused the limb to mortify and affect the bone.” +\

Persian army of Cambyses II

David Klotz of New York University wrote: ““Much like the Roman Emperor Caracalla centuries later, Cambyses seems to have entered Egypt with good intentions, respecting local temples and religious customs. Yet after his failed campaigns, Cambyses stormed back to Memphis, reportedly leaving behind a trail of looting, destruction, and impiety that gave him one of the worst reputations in the ancient world. Many classical authors report that Cambyses stole precious objects from the temples, and the careful damage to the cartouches of Amasis throughout Egypt suggests attacks were primarily directed against his structures during this time. Upon his return to Memphis, the testy Cambyses could not bear to witness celebrations for the newly crowned Apis and he reportedly murdered the sacred calf. Scholars frequently debate the fragmentary evidence from the Serapeum, but the extant records do not entirely disprove the accusations Herodotus recorded. Even if Cambyses granted an official Apis burial early in his reign, this does not mean he could not have killed another during a fit of rage. [Source: David Klotz, New York University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

“Whether the charges of impiety leveled against Cambyses are exaggerations or ideologically charged fabrications of anti- Persian propaganda, documentary evidence indicates that he significantly reduced the fiscal resources of most temples in Egypt. Dillery argued that Herodotus’s native Egyptian informants did not objectively narrate their history, but instead resorted to literary tropes to frame recent events within their mythological worldview. If anything, native accounts of Cambyses recall legends surrounding Seth, the god of chaos, charged with committing numerous impieties in Egypt during the Late Period. A decree of Cambyses is preserved on a Demotic papyrus. Although Cambyses may have simply intended to boost the Egyptian economy, the clergy remembered this period as a regrettable hiatus in temple donations, falling between the more beneficent reigns of Amasis and Darius I.”

Cambyses Military Campaigns as the Ruler of Egypt

After Cambyses firmed up his control of Egypt, he planned expeditions against the Carthaginians, the dwellers in the Oasis of Jupiter Ammon, and the Nubians. He ended up leaving the Carthaginians in peace due to lack of support, but did attempt to bring down Oasis the dwellers and the Nubians. But his armies were unprepared for the harsh conditions and misguided in terms of directions. Cambyses, out of frustration and hopelessness, decided to abandon his plan of attack. “ [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato +]

David Klotz of New York University wrote: “After the interlude at Sais, Cambyses headed south to campaign against Nubia. Kahn recently assumed Cambyses marched entirely on foot, but Herodotus only employed the neutral Greek verb “polemein “to describe this campaign. While this expedition ended in disaster, he apparently captured at least part of Lower Nubia, and official Achaemenid monuments record Kush in their list of subjects beginning with Darius I. The installation of Persian garrisons at Elephantine and Syene reflects the continued engagement with Egypt’s southern frontier during this period. However, the pottery from the Second Cataract fort at Doginarti, previously ascribed to the Saite- Persian Period, has more recently been dated to Dynasties 25-26, and thus no longer confirms Achaemenid domination south of Elephantine. [Source: David Klotz, New York University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

“Frustrated in Nubia, Cambyses returned north, dispatching an expedition against the Oases, apparently via the desert roads linking Thebes to Kharga, only to perish in an unexpected sandstorm. Here, Cambyses was maintaining the foreign policies of the preceding Saite dynasty, who had already begun endowing large settlements and temples in the Egyptian Oases , while simultaneously forging diplomatic ties with the nascent Hellenistic colony of Cyrene in northern Libya. Libya was nominally under Persian control, and the Western Desert underwent significant development under Darius I and his successors.”

Udjahorresnet: A Savior of Egypt or a Persian Collaborator?

It was this Udjahorresnet, high priest and overseer of maritime shipping— not a military admiral as is often claimed—under the reign of Amasis, who halted the imminent destruction of Sais. Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Although the Persian conquest of Egypt was undoubtedly a traumatic, destabilizing event, many Egyptian officials made their peace with the new rulers. Most notable among these was Udjahorresnet, a high-ranking courtier during the reigns of both the final two 26th Dynasty pharaohs, Amasis and Psamtik III, and the first two Persian pharaohs, Cambyses and Darius I. Udjahorresnet is believed to have belonged to a powerful family based in the Nile Delta city of Sais, the capital of the 26th, or Saite, Dynasty. Under Amasis and Psamtik III, Udjahorresnet held a lengthy list of titles, including prince, count, royal seal bearer, sole companion of the pharaoh, true beloved king’s friend, scribe, inspector of council scribes, chief scribe of the great outer hall, administrator of the palace, and overseer of the royal kbnwt vessels. After the Persians seized power, he retained all these titles except the last one and assumed the new position of chief physician. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2023]

Udjahorresnet is one of the few known high officials of the 26th Dynasty to retain his rank under the Persians. His resilience has led some past scholars to label him a collaborator — or even a traitor — who sold out his country to maintain his elevated position. But some now argue that, far from being a turncoat, Udjahorresnet parlayed his closeness to the Persian kings to help preserve Egypt’s traditions of religion and rulership in a time of foreign domination. “On a military level, there was no chance to withstand the Persian invasion, so he was faced with the question of how to go on, how to deal with a very challenging political situation,” says Melanie Wasmuth, an Egyptologist at the University of Helsinki. “It seems that Udjahorresnet made the deliberate decision to convince at least some of his colleagues that the least problematic choice was to come to an agreement with the Persian rulers and fight for a kind of semiautonomy to make sure that as much of Egyptian culture as possible would survive.”

David Klotz of New York University wrote: “ On his oft-discussed statue in the Vatican, Udjahorresnet recounts how he personally interceded with Cambyses during his visit to Sais. Udjahorresnet explained the theological significance of Sais and the local goddess Neith, provided the Great King with an Egyptian titulary, and persuaded him to banish foreign soldiers from the sacred precinct: [Source: David Klotz, New York University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

“His Majesty himself went to the temple of Neith, and kissed the ground for her Majesty, very greatly, like all kings have done. He made a great offering of all good things for Neith, the Mother of God, and the great gods within Sais, like all good kings have done. That his Majesty did this, was because I had made him understand the greatness of her (Neith’s) Majesty: she is the very mother of Ra himself!”

“To label Udjahorresnet a “collaborator” may be unfair. As a prominent member of the indigenous and learned elite, he was perhaps one of the few Egyptians capable of rescuing the temple of Sais from the invading army. Aside from recognizing Cambyses as the new legitimate king—the same way Egyptians had accepted the usurper Amasis a few decades earlier—there is no evidence that Udjahorresnet acted against his fellow Egyptians for personal gain. Instead, he enjoyed a respectable reputation among indigenous Egyptians: he received an impressive tomb in Abusir—work apparently began on this uncompleted sepulture in years 41/42 of Amasis—even though he may have been buried abroad . Furthermore, almost two centuries later, a priest from Sais restored one of his statues in the Ptah temple at Memphis specifically in order to “keep his name alive,” perhaps to honor his rescue of the Neith temple.”

Udjahorresnet Statue — the Primary Source on Udjahorresnet

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine:Udjahorresnet is known largely from a two-foot-tall basalt statue that is believed to have stood in the temple of the creator goddess Neith in Sais and that dates to the first few years of the rule of Darius I. Neith was the city’s patron goddess and her cult was ancient even by Egyptian standards, dating back as far as the Predynastic period, some 5,000 years ago. The goddess was credited with separating night from day and giving birth to the sun god Re. Her cult center at Sais was well established by the time of the Old Kingdom (ca. 2649–2150 B.C.), and the Saite pharaohs rebuilt a New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1070 B.C.) temple to the goddess on a gargantuan scale. In the nineteenth century, explorers found that the temple’s enclosure wall measured 90 feet thick and surrounded an area of roughly half a mile by a third of a mile. In addition to its religious significance, the temple was an important economic and political institution that was home to workshops, artists, and craftspeople. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2023]

Udjahorresnet’s statue is covered with an extensive autobiographical hieroglyphic inscription that includes recollections of his interactions with Cambyses and Darius I. In his dealings with Cambyses in particular, says Marissa Stevens, an Egyptologist and assistant director of the Pourdavoud Center for the Study of the Iranian World at the University of California, Los Angeles, Udjahorresnet outlines how he helped transform the Persian king from a foreign invader into a proper Egyptian pharaoh. Udjahorresnet first describes Cambyses as “great chief of all foreign lands,” a contrast with his description of the Saite pharaohs as “king of Upper and Lower Egypt.” Once Cambyses has conquered Egypt, Udjahorresnet upgrades him slightly, calling him “great ruler of Egypt and great chief of all foreign lands.” Stevens notes that the Egyptian terms “ruler” and “chief” tended to connote otherness and were applied to enemy leaders. Only once Udjahorresnet has conferred upon Cambyses an Egyptian throne name does he describe him in terms befitting a true pharaoh: “king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Mesutire.” “At every stage,” says Stevens, “Cambyses becomes more Egyptianized in his titles until he’s gone through a full initiation.”

Many aspects of Udjahorresnet's statue are typically Egyptian. It captures him standing in the traditional Egyptian pose, with his left foot in front of his right. He holds a small shrine, or naos, in which the god of the afterlife, Osiris, is depicted. It is thus known as a naophorous, or naos-carrying, statue, a style that was very popular in Egypt at the end of the 26th Dynasty and dated back at least a millennium before that. Likewise, significant portions of the statue’s inscription address common Egyptian themes. Udjahorresnet details his offerings to Osiris, lists the ways he has honored Neith, enumerates how he protected his family and saved the people of Sais from an unspecified “very great disaster,” and appeals to the gods to remember his pious deeds. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2023]

However, Henry Colburn, an archaeologist specializing in ancient Iran at New York University, points out that other elements of the statue suggest Udjahorresnet’s identity was more complicated. For instance, he wears a long kilt over a sleeved jacket. These Egyptian garments, says Colburn, combine to resemble the Persian court robe worn by courtiers, soldiers, and the king himself in reliefs at the capital of the Achaemenid Empire, Persepolis, which was founded by Darius I. In addition, Udjahorresnet wears a typically Achaemenid bracelet with a lion head at each end. Likely referring to this bracelet, Udjahorresnet claims in the inscription that his masters gave him golden ornaments as a reward for his service. Colburn notes that this seems to fit into an Egyptian tradition in which pharaohs would give favored courtiers “gold of honor” — though in this case the pharaohs were likely Persian. “He’s got things that make sense if you look at the statue with Persian eyes, and that make sense if you look at the statue and read the inscriptions with Egyptian eyes,” Colburn says. “It’s very remarkable that way.”

The blending of Egyptian and Achaemenid features in Udjahorresnet’s statue is all the more notable as the Achaemenid Empire did not require those it conquered to assimilate. Indeed, its leaders took great pride in the diversity of its subject peoples. “It’s important to the Persians for Egypt to retain a specific identity as Egypt,” says Colburn. “I think they never really exerted any pressure to conform, so it’s remarkable that you get people like Udjahorresnet who do it anyway.” Statues of several other Egyptian officials who served under the Persian pharaohs help to place Udjahorresnet’s choices in context. Ptahhotep, who was overseer of the treasury, probably at the temple of the creator god Ptah in the city of Memphis, made choices similar to Udjahorresnet’s in how he was depicted in his naophorous statue. He also wears Egyptian garments that combine to mimic Persian attire, as well as an Achaemenid-style torc with an ibex head at each end around his neck. However, an official named Horwedja, who served as finance minister, presents as entirely Egyptian in his naophorous statue. He wears a short Egyptian kilt and no jewelry. According to Colburn, Horwedja’s position placed him at a higher rank with greater access to the Persian king or satrap, the king’s governing representative in Egypt, than Ptahhotep — though he was not as elevated as Udjahorresnet. “The standard cynical thinking would be that the highest-ranking Egyptians were most apt to adopt Persian identities,” says Colburn, “but the example of Horwedja shows that that’s not true at all.”

Udjahorresnet and the Persian Rulers Cambyses and Darius I

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Udjahorresnet’s statue is covered with hieroglyphic inscriptions that describe his interactions with the Persian pharaohs Cambyses (reigned 526–522 B.C.) and Darius I (reigned 522–486 B.C.).The throne name that Udjahorresnet selected for Cambyses, Mesutire, translates to “Offspring of Re,” empha-sizing the legitimacy of Cambyses’ rule by invoking the Egyptian religious pantheon. Cambyses’ direct predecessors also had throne names connecting them with the sun god — Psamtik III was Ankhare, “Living Ka of Re,” and Amasis was Khenemibre, “Joined with the Heart of Re.” But Cambyses’ throne name boasted the most intimate connection with the god. “Cambyses most likely had many Persian officials who served as his advisers, but none of them would have been able to come up with the nuance of what Udjahorresnet did in that moment,” Stevens says. “By giving him a closer relationship to the deity than had ever been seen before, Udjahorresnet is indicating that Cambyses didn’t just have the right to rule, he is very much sanctioned by the gods in his takeover of Egypt.” [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2023]

To further establish Cambyses’ bona fides as pharaoh, Udjahorresnet prompted him to turn his attention to the temple of Neith in Sais. At Udjahorresnet’s urging, the inscription states, Cambyses expelled a group of “foreigners” who had taken up residence in the temple, purified it, and restored it to its proper functioning, including employing temple personnel and celebrating feasts and festivals. Finally, Cambyses visited the temple himself and “touched the ground before her very great majesty as every king had done….This his majesty did because I caused him to know the importance of her majesty.” Stevens explains that “Udjahorresnet is doing two very important things with that part of his autobiography: He is being the loyal adviser to the king and simultaneously he is saying, ‘I am so devout and such a good Egyptian, I reminded pharaoh that this is what a good king does to restore Sais to its former glory.’” Likewise, she suggests, Cambyses recognized, quite possibly under Udjahorresnet’s tutelage, the importance of securing the former capital of the dynasty he had overthrown. “Udjahorresnet describes the temple as being in disarray and then Cambyses rebuilds it,” Stevens says. “That’s a very common Egyptian trope, and the fact that he’s utilizing this trope was a strategy, because he knew people would pick up on it: ‘Oh, Cambyses is investing in temple spaces and in the workshops and the craftspeople and the artists who are attached to these temples.’”

Exactly how Udjahorresnet managed to become such a close adviser to Cambyses is unclear. His connection to Sais and his deep understanding of the workings of its temple of Neith were certainly key factors. Wasmuth suggests that, based on the titles he held under the Saite pharaohs, in particular his role as overseer of the royal kbnwt vessels, Udjahorresnet was likely a younger son of a major priestly family. The translation of kbnwt has been debated, with some scholars arguing that it denotes military ships such as triremes, and others arguing that it can describe a shipping fleet. An inscription from Udjahorresnet’s sarcophagus also identifies him as overseer of foreign mercenaries. “It’s clear that at some point he was a major figure in the Egyptian military,” Wasmuth says. “In priestly families, this was not typically a job that was taken by the eldest son, who would inherit the priestly office.” Udjahorresnet’s prospects seem to have improved under Cambyses, when he became chief physician, a position known to involve direct access to the king.

Late in his career, Udjahorresnet appears to have been an adviser to Darius I at the Persian court in Susa in modern-day Iran. According to the inscription on Udjahorresnet’s statue, Darius I sent him back to Egypt to restore an institution called the House of Life, possibly at the temple of Neith in Sais, that had fallen into disarray. Scholars debate what exactly the House of Life was, though it seems to have been a sort of library where essential religious texts were stored. Colburn believes this assignment was a step down from Udjahorresnet’s previous roles under the Persian kings. “It’s important, but it’s nothing like the high courtly position he seems to have had before,” says Colburn. “It’s possible this was a sort of retirement gig. Perhaps Udjahorresnet wanted to go back to Egypt and so the king arranged a comfortable position for him.” This may have reflected a desire to be buried in the land of his ancestors. Wasmuth, however, suggests that the House of Life was also an important repository of medical knowledge and that Darius I may have tasked Udjahorresnet with attending to the institution at a time when Egyptian physicians in his court had failed to properly treat an ankle injury he had suffered. “It’s equally possible that this wasn’t a retirement position, but another important placement in which Darius sends one of his exceedingly loyal, close advisers back to Egypt to make sure things go there as planned,” she says.

Udjahorresnet’s Legacy

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Udjahorresnet was ultimately buried in his home country, in the Abusir necropolis near Memphis. Despite the inclusion of some Persian-inflected attire in his statue, Udjahorresnet’s resting place is a typically Egyptian shaft tomb. Evidence found there during excavations from 1980 to 1993, including tablets in the foundation deposits inscribed with the names of the pharaoh Amasis, suggests that it was under construction around 530 B.C. The inscriptions on the burial chamber’s walls and the inner and outer sarcophagi are all standard Egyptian texts designed to ensure a smooth transition to the afterlife. Archaeologists also uncovered several figurines inscribed with text identifying Udjahorresnet as chief physician. As this was a title he assumed only under the Persian kings, work on the tomb clearly continued after the fall of the Saite pharaohs. No trace of Udjahorresnet’s body has been found in the tomb, and in the past some scholars have suggested that he was never actually buried in it. But, Ladislav Bareš, an Egyptologist at the Czech Institute of Egyptology, who was part of the team that excavated the tomb, points out that it was heavily looted and says that a cache of mummification materials found close to the tomb establishes that Udjahorresnet was indeed buried there. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2023]

Udjahorresnet's naophorous statue is the only depiction of him known to exist today. Based on statue fragments that have been discovered in both Memphis and Cairo, Wasmuth argues that there were likely at least two additional inscribed naophorous statues of him, which she believes stood in the temple of Ptah in Memphis and the temple of the creator god Atum or of Re-Horakhty in the religious center of Heliopolis. Re-Horakhty was a merger of Re and the sky god Horus. “It’s really, really exceptional to have the same type of statue displayed in two or more different temples,” she says. “To me, this argues for a very deliberate display strategy that needs to be explained.” In this case, Wasmuth suggests, the goal was likely to promote the legitimacy of the rule of Egypt by Persian pharaohs, for whom being accepted by the country’s major temple institutions was essential. “The temples are potentially a hotbed for rebellion,” Wasmuth says, “because they are so tied to the Egyptian kingship concept and have the greatest potential to lose something under Persian rule.”

There is evidence suggesting that Udjahorresnet was venerated long after his death, a prestigious distinction for a nonroyal Egyptian figure. One of the few others to be accorded this honor was Imhotep, the architect of the step pyramid at the necropolis of Saqqara for the pharaoh Djoser (reigned ca. 2630–2611 B.C.). Wasmuth points to a fragment of a statue of Udjahorresnet that was discovered in the 1950s in Memphis, where it had been reused in the construction of a pillar. The fragment includes an inscription indicating it was commissioned by a priest of Neith in the fourth century B.C. “I made the name of the chief physician Udjahorresnet live 177 years after his time, since I had rediscovered his statue in a state of ruin,” the inscription reads. This suggests that Udjahorresnet’s achievements were still known and seen as worthy of celebration.

This 11-inch-tall wooden door shows Darius I (right), in the guise of an Egyptian pharaoh, making an offering to the jackal-headed god Anubis (center). The goddess Isis stands behind Anubis.Given that the creation of the new statue may have coincided with a later period when the Persians again ruled Egypt, from 340 to 332 B.C., it’s possible that Udjahorresnet’s example of cooperation was seen as particularly relevant. “You could argue,” says Colburn, “that the Persians were back, so Udjahorresnet, who had developed a way to work with them, once again becomes a useful exemplar.” Udjahorresnet’s model of perpetuating Egyptian traditions under foreign control would be extremely useful over the next few centuries. Egypt experienced nearly 300 years of Macedonian and Greek rule — with the foreign rulers adopting the title of pharaoh and building new temples to the Egyptian gods — before finally being absorbed by the Romans in the first century B.C.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024