Home | Category: Education, Health and Transportation

MEANS OF TRANSPORTATION IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Heidi Köpp-Junk of Universität Trier wrote: “As means of overland travel, mount animals, sedan chairs, or chariots are known—and of course walking. For donkey riding, indirect evidence exists from the Old King-dom in the form of representations of oval pillow- shaped saddles depicted in the tombs of Kahief, Neferiretenef , and Methethi. These saddles were similar to the saddle of the Queen of Punt depicted in a New Kingdom scene in the temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri. Similarly, representations of donkey riding are known from the Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom. The earliest pictorial evidence of a ridden horse dates to the reign of Thutmose III. Horse riding is proven in connection with scouts, couriers, and soldiers and is a mode of locomotion that had an obvious emphasis on speed.” [Source: Heidi Köpp-Junk, Universität Trier, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

Steve Vinson of Indiana University wrote: “Egypt’s most important, most visible, and best-documented means of transportation was its watercraft. However, pack animals, porters, wheeled vehicles, sledges, and even carrying chairs were also used to move goods and people across both short and long distances, and each played an important role. The regular transportation of stone from quarries that might lie far from the river, and grain from the countless large and small farms that existed throughout the Nile Valley, also required the organization and maintenance of integrated transportation facilities and networks that involved both land and water transport. [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“Donkey and, later, camel caravans seem to have been the preferred mode of transport for goods along roads and tracks, as Pharaonic texts such as Harkhuf’s autobiography and the Tale of the Eloquent Peasant suggest, and as archaeological evidence—for example, the donkey hoof- prints from the Toshka gneiss-quarry road mentioned above—shows. The period in which the camel was introduced into, and domesticated in, Egypt remains controversial. Most faunal, iconographic, and textual evidence points to a date sometime in the first millennium B.C., but some have argued for an introduction of the camel as early as the Predynastic Period. The question is complicated because faunal or iconographic evidence for the presence of camels does not necessarily prove camel domestication.”

RELATED ARTICLES: TRANSPORTATION IN ANCIENT EGYPT factsanddetails.com ; INFRASTRUCTURE IN ANCIENT EGYPT: ROADS, COMMUNICATION, WATER TUNNELS africame.factsanddetails.com ; TRAVEL IN ANCIENT EGYPT factsanddetails.com ; LIVESTOCK AND DOMESTICATED ANIMALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Transport in Ancient Egypt” by Robert B. Partridge (1996) Amazon.com;

“Wheeled Vehicle and Ridden Animals in the Ancient Near East” by M. A. Littauer and J. H. Crouwel Amazon.com;

“The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World” by David W. Anthony (2010) Amazon.com;

“Chasing Chariots: Proceedings of the First International Chariot Conference” (Cairo 2012)

by Dr. Andre J. Veldmeijer and Prof. Dr. Salima Ikram (2018) Amazon.com;

“Bronze Age War Chariots” Illustrated (2006) by Nic Fields Amazon.com;

“Chariots in Ancient Egypt: The Tano Chariot, A Case Study”

by Dr. Andre J. Veldmeijer and Prof. Dr. Salima Ikram (2018) Amazon.com;

“Chariots and Related Equipment from Tut'ankhamun's Tomb” by M. A. Littauer, J. H. Crouwel (1985) Amazon.com;

“The Gurob Ship-Cart Model and Its Mediterranean Context: An Archaeological Find and Its Mediterranean Context” by Shelley Wachsmann, Alexis Catsambis, et al. Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The World of Ancient Egypt: A Daily Life Encyclopedia" by Peter Lacovara, director of the Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016) Amazon.com

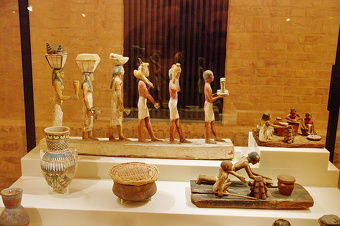

Litters, Sedan Chairs and Palanquins in Ancient Egypt

Men of rank of the Old Kingdom were carried in chairs known as litters, carrying chairs, sedan chairs and palanquins. These typically consisted of a seat with a canopy over it, which was carried on the shoulders of twelve or more servants; men walked by the side with long fans, and waved fresh air to the master, whilst another servant carried skin of water for his refreshment. During the Middle Kingdom we meet with a similar litter, but without a canopy. In one picture, a servant is seen carrying a kind of large shield-umbrella, which might be used not only to shade the master from the sun, but also on a stormy spring day to shelter him from the wind. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

sedan chair of Queen Hetepheres

Steve Vinson of Indiana University wrote: “Carrying chairs appear in the First Dynasty, and images of aristocrats or rulers being carried in such vehicles—some exceptionally elaborate—can be found throughout the Pharaonic Period. Evidence for the use of these chairs beyond the Pharaonic Period is not commonly encountered, but carrying chairs certainly continued to be used—or at least remembered—into the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods. A carrying chair figures in the Ptolemaic First Tale of Setne Khaemwas, in which the character Setne (following his hallucinatory sexual encounter with the femme fatale Tabubue) encounters a “pharaoh” (actually a manifestation of the dead Naneferkaptah, from whose tomb Setne had stolen the magic book that is at issue in the tale), who is being carried on such a chair by his entourage.” [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

Heidi Köpp-Junk of Universität Trier wrote: “The sedan chair was an elite means of transport. Primarily men appear as occupants; there are only a few depictions of, and texts referring to, women in carrying chairs. Very occasionally other types of chair, such as the donkey litter, are depicted, but these are only attested in the 5th Dynasty. Significantly, the carrying chairs of the New Kingdom were depicted only in a religious context; it therefore appears that a change in the chair’s function took place from a non-religious to a religious use. [Source: Heidi Köpp-Junk, Universität Trier, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Palanquins were used for short journeys and presumably for long distances as well, being the only suitable means of highly esteemed passenger transportation in the Old and Middle Kingdom . From their first appearance, the litter was a status symbol, used by the king and royal family. From the 3rd Dynasty, the group of users expanded to include high officials. In the New Kingdom, again the occupants were solely the pharaoh and his family. At this point the chariot replaced the carrying chair and the elite used it as a prestigious means of locomotion.”

Donkeys in Ancient Egypt

Donkeys were widely used as beasts of burden and a means of travel. The donkey is as it were created for the particular conditions found in Egypt; it is an indefatigable and, in good examples, also a swift animal, and is able to go everywhere. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

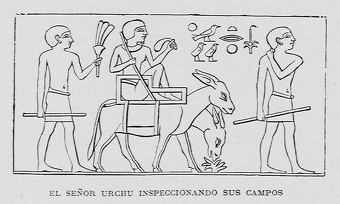

Yet it seems to have been considered scarcely proper to use it for riding; we never find any one represented riding on a donkey, though there is an unmistakable donkey-saddle in the Berlin Museum, which vouches for this practice, at any rate during the New Kingdom. Nevertheless there was no impropriety in a man of rank traveling in the country in a kind of seat fastened to the backs of two donkeys, as we see by a pleasing representation of the time of the Old Kingdom.

In an image called “Journey in a Donkey Sedan-chair” two runners accompany their master, one in front to clear the way for him, the other to fan him and to drive the donkey. In a letter from the New Kingdom there is the mention of the shoeing of a donkey with bronze.

Wheeled Vehicles in Ancient Egypt

human-pulled cart from Ancient Egypt

Heidi Köpp-Junk of Universität Trier wrote: “Roughly half a dozen two-wheeled carts and nearly 30 types of four- to eight-wheeled wagons, equipped with discs or spokes, are known from ancient Egypt. They were only used for the transfer of freight, and not for passengers. Carts and wagons transported the loads that were too heavy for donkeys and oxen, whereas sledges were used for even larger weights, thus avoiding the risk of broken axles . This explains why sledges were not replaced by carts and wagons: their different load capacities complemented one another. [Source: Heidi Köpp-Junk, Universität Trier, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

Steve Vinson of Indiana University wrote: “The Egyptians of the Pharaonic Period did have at least some wheeled vehicles. Most evidence for these comes from depictions or archaeological remains of chariots, which appear for the first time at the very end of the Second Intermediate Period and then come to be common military and royal vehicles in the New Kingdom. The use of carts for basic transportation in the Pharaonic Period is much harder to trace, either archaeologically or iconographically, but at least one Eighteenth Dynasty Theban tomb- relief fragment does show a wheeled cart or wagon drawn by oxen in an agricultural scene. [Source:Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“Whether the dearth of parallels to this scene shows that such carts were only rarely used in Egypt, or whether the motif was not taken up in other tombs simply because it was not part of the traditional iconographic vocabulary of agricultural scenes, is difficult to say. Supply carts are also shown in reliefs accompanying the account of Ramesses II’s battle against the Hittites at Kadesh, but of course the venue here is not Egypt proper. A cart drawn by four oxen in the middle of a war scene of Ramesses III’s account of the defeat of the Tjeker would similarly suggest the vehicle’s foreign origin. Wheeled vehicles from earlier periods are rare. As noted above, they became common in Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt.

Carts and Carriages in Ancient Egypt

During the New Kingdom, litters fell into disuse except on ceremonial occasions; the reason seems to have been that in the meantime a far better means of conveyance had been introduced into Egypt — the horse and carriage. It has been conjectured that the Egyptians owed the horse and carriage to their conquerors the Hyksos; but this has not been proved, though, on the other hand, we may consider it as certain that they were introduced during the dark period between the Middle and the New Kingdom, for horses and chariots are represented for the first time on the monuments of the 18th dynasty. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The word htor, which in later times signified horse, occurs once at any rate as a personal name on a stela of the 13th dynasty; but as the original meaning of this word signifies two animals yoked together it might therefore be used in the older period to indicate two oxen ploughing, as well as in later times in speaking of the horses of a carriage.

From the Semites, and indeed from the Canaanites, that the Egyptians borrowed the two forms of cartm which became the fashion during the New Kingdom, and were used until quite late times — the “merkobt” and “agolt. Whether there were vehicles of any kind in Egypt before the introduction of the above must remain uncertain.

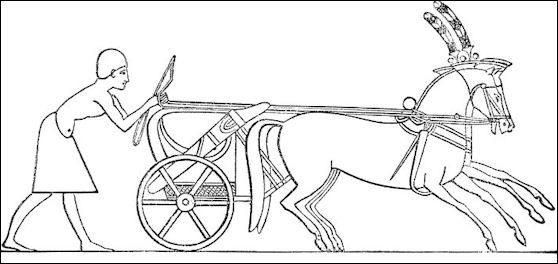

Concerning the agolt, we only know that it was drawn by oxen, and used for the transport of provisions to the mines; " it was therefore a kind of baggage waggon. More is known about the merkobt, which was used for driving for pleasure, for traveling," for hunting in the desert,' and in war. It was a small very light vehicle, in which there was barely room for three persons to stand, so light in fact that it was said by an Egyptian poet that a carriage weighed five deben and its axle weighed three — this must of course be a gross exaggeration, for the very lightest carriage would weigh more than eight deben (less than a kilogram)

The merkobt'' was essentially a chariot. It never had more than two wheels; these were carefully made of different wood or metal, and had four, or more usually six spokes. The axle carried the body of the carriage, which consisted of a floor, surrounded in front and at the sides with a lightly-hung wooden railing. The pole was let into this flooring, and for better security was fastened by straps to the railing; at the end of the pole there was a cross-bar, the ends of which were bent into a hook form, and served for the fastening of the harness.

Ancient Egyptian Harnesses and Carriage Gear and Personnel

The harness used on ancient Egyptian carriages was of a remarkable simplicity. Traces were at this time unknown to the Egyptians; round the breasts of the two horses there passed a broad strap, which was fastened to the transverse bar of the pole, and by this alone the carriage was drawn. In order that this strap should not rub the necks of the horses, the Egyptians put behind it underneath a broad piece of leather, to the metal covering of which the strap was fastened; a smaller strap was passed from the back piece under the belly to the pole, to prevent the broad strap from shifting from its place. Reins were used to guide the horses; they passed over a hook in the back piece to the bits in the mouths of the horses. The fashion of head-gear resembled that used everywhere at the present day, and from the time of the 19th dynasty blinkers also were employed.

All Egyptian carriages were built in the above manner, and were only distinguished from each other by the greater or less luxury of the equipment. In many the straps of the harness and the leather covering of the frame of the carriage were colored purple; all the metal parts were gilded; the plumes of the horses were stuck into little heads of lions, and even the wheel-nail was carved into the shape of a captive Asiatic.

This rich equipment alone shows what value the Egyptians put upon their carriages and horses. Wherever it is possible they are represented, and it is a favorite theme of the litterateurs of the time to describe and extol them. The coachman, the Kat!ana (a foreign term by which he was called), is found in every household of men of rank; ' and at court the office of “first Kat'ana to his Majesty “was such an important post that it was held even by princes. The favorite horses of the king, the “first great team of his Majesty," bear high-sounding names; thus, for instance, two belonging to Seti I. are called “Amun bestows strength," and “Amun entrusts him with victory," the latter bears also the additional name “Anat (the goddess of war) is content. " ' We learn from these names that the horses were trained to go into battle; and consequently fiery high-spirited horses were preferred. Thus the horses of Ramses II. required, in addition to the driver, three servants to hold them by the bridle,' and in other places Egyptian horses are usually represented rearing or pawing the ground impatiently.

Ancient Egyptian Chariots

Chris Carpenter to Minnesota State University, Mankato wrote: “The Egyptians didn't invent the chariot but as things go they did improve upon the idea... The Egyptian chariot was unique in that it was constructed to be handsome and light in weight. This was probably due to a lack of wood along the Nile River. [Source: Chris Carpenter, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com, Edwin Tunis, “Wheels: A Pictorial History,” Thomas Y. Crowell Company; New York, 1955 pg. 13-15. +]

Heidi Köpp-Junk of Universität Trier wrote: “The earliest written evidence for chariots dates to the 17th Dynasty. It was used for warfare, hunting, sports, and also for travel. Its application in warfare is well attested and often discussed. A number of hunting scenes displaying pharaohs on chariots are known; some are attested for private persons as well. A rare instance of its sportive role is shown in a representation of Amenhotep II at Karnak. Chariot races such as those known from ancient Rome are not attested in Pharaonic Egypt. [Source: Heidi Köpp-Junk, Universität Trier, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The chariot was the supreme mode of locomotion for the elite for private and public purposes and an important status symbol in the New Kingdom. It was used for visits and inspections by pharaohs, such as Amenhotep II, Thutmose IV, and Akhenaton, as well as high officials. Women are also depicted in chariots.

“The suitability of the chariot for long-distance travel was limited since its fragile spoked wheels needed even and compact soil; it was not capable of being driven cross-country on uneven, sandy, or rocky ground, especially at high speeds. The oldest chariot found in Egypt, now in the Museum of Florence, has a total weight of only 24 kg, and the tread of its wheels is only 2 centimeters wide. With some accommodations, chariots were nevertheless brought on long-distance journeys: when the ground was prepared in advance or geologically solid enough, they could be used, even in the desert. According to a text from the reign of Ramesses IV, an expedition to the Wadi Hammamat consisted of 8,361 members, including one royal chariot-driver, 20 stable masters, 50 charioteers and, according to Schulman, the same number of chariots belonging to them. Papyrus Anastasi describes the crossing of a mountain pass leading from the coastal plain to Megiddo, with chariots being taken along. Over uneven, rough, or hilly terrain, a chariot could be carried on the shoulders of a single man; due to its light weight it did not need to be dismantled.

“The chariot was the fastest, but also the most expensive, means of travel. Apart from the chariot itself, horses had to be bought and maintained, and a staff needed to be employed for the maintenance and care of both. Therefore, at the beginning of the 18th Dynasty, only the king and a few high officials could afford them. In contrast, about 2,000 chariots have been estimated for the Egyptian army of the 19th Dynasty. This gives an indication of the increasing use of the chariot. How many additional chariots were privately owned is uncertain.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN WEAPONS, CHARIOTS, FIGHTING BOATS AND FORTRESSES africame.factsanddetails.com

.jpg)

chariot

Design of Ancient Egyptian Chariots

Chris Carpenter to Minnesota State University, Mankato wrote: “The Egyptians designed the chariot with the human standing directly over the axle of the chariot. By accomplishing this there was less stress put on the horse(s) because the rider’s weight was distributed to the chariot than to the horse. [Source: Chris Carpenter, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com, Edwin Tunis, “Wheels: A Pictorial History,” Thomas Y. Crowell Company; New York, 1955 pg. 13-15. +]

“The design of the chariot of two wheels and were squeaky and creaked. Basically they were heard wherever they went. The Egyptians didn’t like this idea, and they lined the hubs and covered the axle with copper or bronze plates. The design of the chariot consisted of a number of new and unique ideas to make their chariot stand out. The hub was long and slender, and the spokes were light and nicely shaped. The fellies were one to and held by a spoke. The fellies, inserted in the spoke, were bent, shaped, and joined with a long lap. The tires were made of wood and were shaped in sections. They were attached to the wheel lashing made of rawhide. This lashing technique was unique in that they passed it through slots in the tire sections. The reasoning for this was to keep the lashing from coming in contact with the ground, thus extending its life by lessening the wear and tear. +\

“A pole that is attached to a yoke pulls the chariots. The yoke is attached to the horses’ back by a saddle-pads using girths around the bellies to hold them in place. The Egyptian had two types of chariots, and according to the source the only difference seems to be in the wheels. The Egyptian war-chariot had six spokes while the carriage chariots had only four. The reasoning behind this difference is probably due to the extra support needed in the war-chariot based on the stress that can be put on them is higher than that of the carriage chariot.” +\

First Wheels and Wheeled Vehicles

The wheel, some scholars have theorized, was first used to make pottery and then was adapted for wagons and chariots. The potter’s wheel was invented in Mesopotamia in 4000 B.C. Some scholars have speculated that the wheel on carts were developed by placing a potters wheel on its side. Other say: first there were sleds, then rollers and finally wheels. Logs and other rollers were widely used in the ancient world to move heavy objects. It is believed that 6000-year-old megaliths that weighed many tons were moved by placing them on smooth logs and pulling them by teams of laborers.

Early wheeled vehicles were wagons and sleds with a wheel attached to each side. The wheel was most likely invented before around 3000 B.C.”the approximate age of the oldest wheel specimens — as most early wheels were probably shaped from wood, which rots, and there isn't any evidence of them today. The evidence we do have consists of impressions left behind in ancient tombs, images on pottery and ancient models of wheeled carts fashioned from pottery.◂

Evidence of wheeled vehicles appears from the mid 4th millennium B.C., near-simultaneously in Mesopotamia, the Northern Caucasus and Central Europe. The question of who invented the first wheeled vehicles is far from resolved. The earliest well-dated depiction of a wheeled vehicle — a wagon with four wheels and two axles — is on the Bronocice pot, clay pot dated to between 3500 and 3350 B.C. excavated in a Funnelbeaker culture settlement in southern Poland. Some sources say the oldest images of the wheel originate from the Mesopotamian city of Ur A bas-relief from the Sumerian city of Ur — dated to 2500 B.C.”shows four onagers (donkeylike animals) pulling a cart for a king. and were supposed to date sometime from 4000 BC. [Partly from Wikipedia]

In 2003 — at a site in the Ljubljana marshes, Slovenia, 20 kilometers southeast of Ljubljana — Slovenian scientists claimed they found the world’s oldest wheel and axle. Dated with radiocarbon method by experts in Vienna to be between 5,100 and 5,350 years old the found in the remains of a pile-dwelling settlement, the wheel has a radius of 70 centimeters and is five centimeters thick. It is made of ash and oak. Surprisingly technologically advanced, it was made of two ashen panels of the same tree. The axle, whose age could not be precisely established, is about as old as the wheel. It is 120 centimeters long and made of oak. [Source: Slovenia News]

First Domesticated Horses

The first domesticated horses appeared around 6000 to 5000 years ago. The first hard evidence of mounted riders dates to about 1350 B.C. Uncovering information about ancient horsemen however is difficult. They left behind no written records and relatively few other groups wrote about them. For the most part they were nomads who had few possession, and never stayed in one place for long, making it difficult for archeologists — who have traditionally excavated ancient cities and settlements of settled people — to dig up artifacts connected with them.

For similar reasons it is difficult to work out how different horsemen groups interacted and how individuals within the group behaved. What little is known about group interaction has been learned mostly from the work of linguists. Most of what is known about their behavior is based on observations of modern groups or a hand full of descriptions by ancient historians.

Based on these sources, scholars believe that early nomadic horsemen lived in small groups, often organized by clan or tribe, and generally avoided forming large groups. Small groups have more mobility and flexibility to move to new pastures and water sources. Large groups are much more unwieldy and more likely to generate feuds and other internal problems. On the steppe there generally was enough land for all so the only time horsemen needed to unite was to face a common threat.

The Eurasia steppe is the only place that horses survived after the last Ice Age. Domestication is believed to have occurred around 3000 B.C. when horses suddenly appeared in places where they hadn't been seen before like Turkey and Switzerland. It is difficult to pin down when domestication took place partly because the bones of wild horses and domesticated horses are virtually the same. [Source: William Speed Weed, Discover magazine, March 2002]

Ramesses II on a chariot

Horses are believed to have been domesticated from wild horses from Central Asia about 6,000 years ago. Ancient men viewed horses primarily as a source of meat and hunted them like other animals. One effective method of hunting horses was driving them over cliffs.

See Separate Article ANCIENT HORSEMEN AND THE FIRST WHEELS, CHARIOTS AND MOUNTED RIDERS factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024