Home | Category: Education, Health and Transportation

INFRASTRUCTURE IN ANCIENT EGYPT

from Secrets of the Pyramids secretofthepyramids.com

The Egyptians built canals and irrigation systems. They didn’t make so many roads. Roads were not so important because they relied on the Nile for transportation. In 2300 B.C. the ancient Egyptians built channels through the first cataract of the Nile, where the Aswan Dan stands today. This helped open the way for trade between the Pharaohs and Africa. Messages were sent along the Nile. Seals were the equivalent of signatures. They were applied on wet mud with a paint-roller like cylinder.

Ancient Egyptians are famous for their pioneering and mastery of hydraulics through canals for irrigation purposes and barges to transport huge stones. For example, according to CNN: Water from ancient streams flowed into a system of trenches and tunnels that surrounded the Step Pyramid. A theorized water treatment system would not only allow for water control during flood events, but also would have “ensured adequate water quality and quantity for both consumption and irrigation purposes and for transportation or construction,” said Dr. Guillaume Piton, a researcher with France’s National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment, or INRAE, based at the Institute of Environmental Geosciences of the University Grenoble Alpes. [Source Taylor Nicioli, CNN, August 6, 2024]

RELATED ARTICLES: TRANSPORTATION IN ANCIENT EGYPT factsanddetails.com ; LAND TRANSPORT IN ANCIENT EGYPT: CARRIAGES, LITTERS, CARTS africame.factsanddetails.com ; TRAVEL IN ANCIENT EGYPT factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Nile: History's Greatest River” by Terje Tvedt (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Gift of the Nile?: Ancient Egypt and the Environment (Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections) by Egyptian Expedition, Thomas Schneider, Christine L. Johnston (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Nile: Traveling Downriver Through Egypt's Past and Present” by Toby Wilkinson (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Nile and Ancient Egypt: Changing Land- and Waterscapes, from the Neolithic to the Roman Era”, Illustrated by Judith Bunbury (2019) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Irrigation: A Study of Irrigation Methods and Administration in Egypt (Classic Reprint) by Clarence T. Johnston (1901) Amazon.com;

“Garden of Egypt: Irrigation, Society, and the State in the Premodern Fayyum by Brendan Haug (2024) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Technology and Innovation” by Ian Shaw (2012)

Amazon.com;

“Engineering in the Ancient World” by J. G. Landels (2000) Amazon.com;

“Transport in Ancient Egypt” by Robert B. Partridge (1996) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Ships and Shipping” by William Franklin Edgerton (2023) Amazon.com;

“A Categorisation and Examination of Egyptian Ships and Boats from the Rise of the Old to the End of the Middle Kingdoms by Michael Allen Stephens (2012) Amazon.com;

“Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World” by Lionel Casson (1995) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Boats and Ships” by Steve Vinson (2008) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Construction and Architecture” by Somers Clarke and R. Engelbach (2014) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Towns and Cities” by Eric Uphill (2008) Amazon.com;

“Building in Egypt” by Dieter Arnold (1991) Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

“The World of Ancient Egypt: A Daily Life Encyclopedia" by Peter Lacovara, director of the Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016) Amazon.com

Postal Service in Ancient Egypt

Facilities for correspondence by letter seem to have been early developed; these were doubly valuable on account of the long distances we have alluded to above. We know that the art of polite letter-writing was considered one of the most necessary accomplishments to be acquired in the schools; but little is known concerning the sending of such letters. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

When, for instance, we read that the writer is disappointed of the answer he had been expecting to his letter, and finally writes to his friend that he is doubtful whether his boy by whom he had sent the letter had arrived, reference is evidently made to a private messenger. There are however passages which seem to indicate that there was an established communication by messengers regularly and officially sent out; we read for instance: “Write to me by the letter-carriers coming from thee to me," and “write to me concerning thy welfare and thy health by all those who come from thee; . . . not one of those whom thou dost send out arrives here.

The same letter from which we have quoted the latter passage gives us also a possible indication of the manner in which small consignments were sent from one to another. The writer excuses himself for only sending fifty loaves of bread to his correspondent; the messenger had indeed thrown away thirty because he had too much to carry; he had also omitted to inform him in the evening of the state of things, and therefore he had not been able to arrange it all properly. "'

Vast Tunnel Found Beneath Ancient Egyptian Temple

In 2022, scientists announced the discovery of a vast water tunnel — about two meters (6.6 feet) high — beneath a temple in Taposiris Magna, an ancient city located west of Alexandria, Egypt. It's thought that, at one time, the massive tunnel was used to transport water to local people. Discovered by an Egyptian-Dominican Republic archaeological team, the Egyptian tunnel is 1.3 kilometers (4,281 feet) long. [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science December 27, 2022

Ancient Egyptian builders constructed the tunnel at a depth of about 20 meters (65 feet) beneath the ground, Kathleen Martínez, a Dominican archaeologist and director of the team that discovered the tunnel, told Live Science. "[It] is an exact replica of Eupalinos Tunnel in Greece, which is considered as one of the most important engineering achievements of antiquity," Martinez said. The Eupalinos tunnel, in Samos, a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, also carried water. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, November 14, 2022]

According to Live Science: The archaeology of the Taposiris Magna temple is complex. Parts of it are submerged under water and the temple has been hit by numerous earthquakes over the history of its existence, causing extensive damage. The tunnel at Taposiris Magna dates to the Ptolemaic period (304 B.C. to 30 B.C.), a time when Egypt was ruled by a dynasty of kings descended from one of Alexander the Great's generals.

Finds within the tunnel included two alabaster heads: one of which likely depicts a king, and the other represents another high-ranking person, Martinez said. Their exact identities are unknown. Coins and the remains of statues of Egyptian deities were also found in the tunnel, Martinez said.

At the time the tunnel was built, Taposiris Magna had a population of between 15,000 and 20,000 people, Martinez said. The tunnel was built beneath a temple that honored Osiris, an ancient Egyptian god of the underworld, and Isis, an Egyptian goddess who was Osiris's wife.

Roads in Ancient Egypt

Steve Vinson of Indiana University wrote: “Although land transportation is less visible to us in the iconographic record than travel by boats or ships, there is an abundant and growing archaeological inventory of formal roads and informal overland routes that show the crucial importance of land transport for the functioning of Egypt’s economy and culture. In the area of the flood-plain itself, ancient routes are often difficult to trace, with the exception of paved, ceremonial roads like the avenue of sphinxes linking the Karnak and Luxor temples. The ubiquity of canals, basins, and dykes will certainly have complicated land-travel, particularly during flood season; although dykes will also have provide raised routes that could be traversed to avoid fields, especially in times of high water. Outside of the flood plain, archaeological exploration of Egypt’s desert transportation networks is an extremely promising field. [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“Comparatively few paved roads have been discovered from Pharaonic Egypt, but they are not unknown: a paved road linking Widan al-Faras and Qasr al-Sagha in the northern Fayum appears to have been constructed in the early third millennium B.C., and was described as the world’s earliest paved road. The road, 2.4 meters wide, was paved with slabs of sandstone and logs of petrified wood. Another early paved road was constructed to link quarries at Abusir to the Fifth Dynasty pyramids about 1.2 kilometers away. This more-substantial road was approximately ten meters (or 20 cubits) wide, built on a 30- centimeter-deep bed of mud-brick and local clay, and finished off with a paving of field- stones mortared together with clay.

Road in Giza used to transport stones to the Pyramids

“Although road surfaces were not often paved along their entire route, stone fill at least may have been used to even out the surface of a path; one example comprises the stone causeways constructed on a 17- kilometer route linking Amarna and Hatnub. Over relatively short distances, reinforced and stabilized tracks for hauling heavy loads of stone to pyramid construction sites were laid using heavy wooden members from derelict ships, then covering them over with limestone chips and mortar. In other cases, roads might simply consist of a track systematically cleared of gravel and debris, and marked with stelas, cairns, and campsites.

Among the most impressive of these early roads are two routes that appear to begin near the Mastaba el-Faraun at Dahshur and lead to the northern and southern Fayum, respectively. These routes were discovered in 1887 by Petrie, who reported that each is remarkably broad—on average more than 25 meters in width—marked along each side with mounds of rubble that had been swept from the road surface, which is otherwise unpaved. The more southerly road is also furnished with distance markers, regularly placed at intervals of about 3.3 kilometers.”

Many of the roads in the desert, mountains, and rural areas are tracks. Some tracks are surprising hard and smooth. Generally, though, they are bumpy and in poor condition. After it rains they often become impassable. Off the beaten track, people on the move have to deal with quagmires (during the rainy season), deep sand, deep ruts, big rocks, dust, steep hills, landslides, and washed out surfaces. They also presumably had to deal with various animals in the roads.

World's Oldest Paved Road Found in Egypt

The world's oldest known paved road is a 7½-mile-long, 6-foot-wide road made of slabs of limestone and sandstone, located near the Danshur pyramids, 43 miles southwest of Cairo. Built between 2600 and 2200 B.C. the road was used to transport basalt on human-drawn sleds from a quarry on the Nile to building sites. Similar roads have not been found near other quarries. Scientist speculate the paving stones made rolling the basalt stones much easier.

John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “In the Old Kingdom of ancient Egypt, a time of grand architecture beginning about 4,600 years ago, demand for building stones for pyramids and temples led to the opening of many quarries in the low cliffs near the Nile River. To make it easier to transport the heavy stones from one of these quarries, the Egyptians laid what may have been the world's first paved road. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, May 8, 1994]

Research geologists mapping the ancient Egyptian stone quarries have identified a seven-and-half-mile stretch of road covered with slabs of sandstone and limestone and even some logs of petrified wood. The pavement, they concluded, facilitated the movement of human-drawn sleds loaded with basalt stone from a nearby quarry to a quay for shipment by barge across the lake and on the Nile to construction sites.

"Here is another technological triumph you can attribute to ancient Egypt," Dr. James A. Harrell, a professor of geology at the University of Toledo, Ohio, told the New York Times. Dr. Harrell and Dr. Thomas Bown, a research geologist at the United States Geological Survey in Denver, mapped the road in 1993 and reported their findings at a meeting of the Geological Society of America. They said that pottery fragments at a quarry and a camp for the ancient stone workers, both discovered near the road, helped date the site to the period of the Old Kingdom, about 2600 to 2200 B.C., when major technological advances were being made, but before Egypt's political zenith. The oldest previously known paved road, made of flagstone and dated no earlier than 2000 B.C., was in Crete.

Pyramids area

The Egyptian paved road, with an average width of six and a half feet, ran across desert terrain 43 miles southwest of modern Cairo. Remnants of the road were first observed early this century, but its full extent and significance were not recognized until last year, when Dr. Bown and Dr. Harrell discovered a large basalt quarry at one end of the road.This dark volcanic stone was favored in monumental construction for pavements inside mortuary temples at Giza, the site of the Great Pyramids, and also for royal sarcophagi. Egyptologists have suggested that the black rock was popular for funerary uses because it symbolized the dark, life-giving Nile mud. Water Link to Nile

The road ran from the quarry to the northwest shore of ancient Lake Moeris, now vanished, which would have provided a water link to the Nile each summer in flood time. The only surviving trace of the lake is a much-reduced body of water called Birket Qarun.As the two geologists reported, the pavement stones bore no deep grooves or other marks that might have been made by direct contact with the wooden runners of the stone-laded sleds. They speculated that logs were laid over the stones.

No similar paved roads have been found near other quarries, Dr. Harrell said, noting that perhaps the distances involved made pavement impractical. Apart from some construction ramps associated with the pyramids, the geologists said, there are no other paved roads known from ancient Egypt. Wheeled wagons were not generally used there until many centuries after this road was built.

Road Networks in Ancient Egypt

Steve Vinson of Indiana University wrote: “Overland routes branched off from the Nile Valley to take Egyptian work crews to quarrying regions in the eastern desert, from which building stone, semi-precious stones, and gold were obtained for Egyptian elite consumption and for export; the same routes continued on to the Red Sea coast, and so constituted a vital link between the Nile and the maritime routes in the Red Sea and Indian Oceans. Westward overland routes linked the Nile Valley to the oases in the western deserts, and the oases to each other. As we read in the Sixth Dynasty autobiography of Harkhuf, one of these routes, designated the “oasis road,” appears to have left the Nile Valley around Abydos, and then to have continued south towards Nubia, thus complementing the Nile River route. At the very end of the Second Intermediate Period, this oasis route was the venue of one of the world’s first recorded espionage missions: agents of the Seventeenth Dynasty Theban king Kamose intercepted a message from the Hyksos king in the Delta city of Avaris to a newly crowned Nubian king, south of Egypt, urging him to join the Hyksos in an alliance to crush Kamose’s bid to re-establish a united monarchy in Egypt. Clearly, the Hyksos had hoped that use of the desert routes would enable their couriers to bypass the Egyptians. [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

map of the rock tombs of Amarna from 1903

“In the north, the “Way (or Ways) of Horus” was the name for a road along the northern Sinai Peninsula leading into southern Palestine, but other desert routes penetrated the peninsula itself . Archaeological evidence, including incised Egyptian storage jars, shows that the north Sinai route was already in heavy use in the late Predynastic and Early Dynastic Periods, connecting Egypt with both Canaanite communities and what appear to have been Egyptian settlements . Indeed the appellation “Way of Horus” (wAt 1r) occurs in the Pyramid Texts. The route was certainly used at all times by merchants, but in periods in which the Egyptian state had interests in Palestine, it was a strategic military route as well. This was especially marked in the New Kingdom, particularly in the reign of Thutmose III, who launched repeated campaigns in Syria-Palestine. Throughout the New Kingdom there is substantial evidence of Egyptian military traffic along the route. In the Ramesside Period, the route was marked by fortified garrisons and way stations, depicted in a relief of Sety I on the northern exterior wall of the Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak. Even further afield, merchant caravans traveled overland between Egypt and Mesopotamia.

“Desert routes in Egypt tended to follow natural wadis, such as the Wadi Hammamat, which connected the Nile Valley to the Red Sea. Routes were often marked with stone cairns to keep travelers on their way, as well as stelas, huts, and small shrines. The provision of water along desert routes was important and the discovery of water sources could be seen as an act of divine favor. In all periods, heavily used routes gradually accumulated debris in the form of potsherds or other trash left by travelers, and are also often marked by rock-art sites. Much such evidence has been discovered and admirably published by the Theban Desert Road survey under the direction of John Darnell of Yale University, who has intensively explored the network of roads used to short-cut the Nile’s Qena Bend with a number of routes running from the vicinity of Thebes/Luxor in the southeast, northwest towards Hu, and from there, eastward towards the oases. Darnell has established that this area was well traveled during multiple periods of Pharaonic history, and his results suggest how much more there is to learn about Egyptian road networks.

“In the Roman Period especially, desert routes are also marked by guard-posts and watch-towers , and along some routes, at least, tolls were charged for people and goods; presumably this was to provide revenue to support the cost of maintaining and protecting the routes. The famous “Koptos Tariff” was inscribed near Koptos under the Roman emperor Domitian in his ninth year (89 – 90 CE). The inscription lays out charges assessed for various classes of persons, animals, or items traveling or being transported along the desert route. Tolls varied widely—a “Red Sea skipper” paid eight drachmas, while “women for companionship” were assessed 108 drachmas.”

Roads at Amarna

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “The city incorporated several thoroughfares, generally running north-south, the most important of which is now known as the Royal Road. It linked the palaces at the north of the Amarna bay to the Central City and then continued southwards, with a slight change of angle, through the Main City. It is just possible that part of its northern span was raised on an embankment, a mud-brick structure north of the North Palace, cleared briefly in 1925, perhaps serving as an access ramp. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The line of the road from the North Palace through the Central City, if projected southwards, also passes directly by the Kom el-Nana complex near the southern end of the site, suggesting that it was used in laying out the city. Thereafter, the Royal Road probably remained an important stage for the public display of the royal family as they moved between the city’s palaces and temples.

The low desert to the east of the city was crisscrossed by a network of roadways : linear stretches of ground, c. 1.5-11 meters in width, from which large stones have been cleared and left in ridges along the road edges. The most complete survey of the road network is that of Helen Fenwick; its full publication is pending. The roads probably served variously as transport alleys, patrol routes, and in some cases as boundaries, and suggest fairly tight regulation of the eastern boundary of the city. Particularly well-preserved circuits survive around the Workmen’s Village and Stone Village. The roadways are among the most vulnerable elements of Amarna’s archaeological landscape, although protected in part by their isolated locations.”

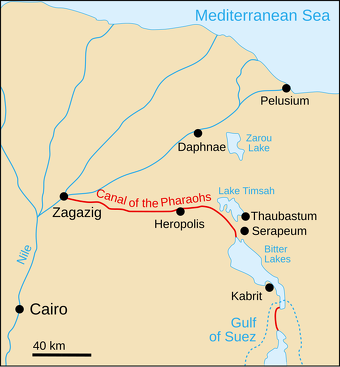

Canal of the Pharaohs

The Canal of the Pharaohs, also called the Red Sea Canal, Ancient Suez Canal or Necho's Canal, is a precursor of the Suez Canal, constructed in ancient times and kept in use, with intermissions, until being closed in A.D. 767 for strategic reasons during a rebellion. It followed a different course from its modern counterpart, by linking the Nile to the Red Sea via the Wadi Tumilat. Work began under the pharaohs. According to Darius the Great's Suez Inscriptions and Herodotus, the first opening of the canal was under Persian king Darius the Great, but later ancient authors like Aristotle, Strabo, and Pliny the Elder claim that he failed to complete the work. Another possibility is that it was finished in the Ptolemaic period under Ptolemy II, when engineers solved the problem of overcoming the difference in height through canal locks.

The canal was probably first cut or at least begun by Necho II (r. 610–595 BC), in the late 7th century B.C. Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “Psammetichus had a son, Necos, who became king of Egypt. It was he who began building the canal into the Red Sea, which was finished by Darius the Persian. This is four days' voyage in length, and it was dug wide enough for two triremes to move in it rowed abreast. It is fed by the Nile, and is carried from a little above Bubastis by the Arabian town of Patumus; it issues into the Red Sea. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

Digging began in the part of the Egyptian plain nearest to Arabia; the mountains that extend to Memphis (the mountains where the stone quarries are) come close to this plain; the canal is led along the foothills of these mountains in a long reach from west to east; passing then into a ravine, it bears southward out of the hill country towards the Arabian Gulf. Now the shortest and most direct passage from the northern to the southern or Red Sea is from the Casian promontory, the boundary between Egypt and Syria, to the Arabian Gulf, and this is a distance of one hundred and twenty five miles, neither more nor less; this is the most direct route, but the canal is far longer, inasmuch as it is more crooked. In Necos' reign, a hundred and twenty thousand Egyptians died digging it. Necos stopped work, stayed by a prophetic utterance that he was toiling beforehand for the barbarian. The Egyptians call all men of other languages barbarians. 159.

“Necos, then, stopped work on the canal and engaged in preparations for war; some of his ships of war were built on the northern sea, and some in the Arabian Gulf, by the Red Sea coast: the winches for landing these can still be seen. He used these ships when needed, and with his land army met and defeated the Syrians at Magdolus,66 taking the great Syrian city of Cadytis67 after the battle. He sent to Branchidae of Miletus and dedicated there to Apollo the garments in which he won these victories. Then he died after a reign of sixteen years,

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024