Home | Category: Government, Military and Justice

THREATS TO THE MESOPOTAMIA- EGYPTIANS

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: In its 3,000-year history as a state, ancient Egypt had a complicated, constantly changing set of relations with neighboring powers. With the Libyans to the west and the Babylonians, Hittites, Assyrians, and Persians to the northeast, Egypt by turns waged war, forged treaties, and engaged in mutually beneficial trade. But Egypt’s most important and enduring relationship was, arguably, with its neighbor to the south, Nubia

According to the Gale Encyclopedia of World History: The powerful Hittites of Anatolia (modern Turkey) posed a constant threat to the pharaohs of the New Kingdom, though an uneasy stalemate usually prevented full-scale conflict. Then, in 1208 B.C., a mysterious group known to its opponents as the Sea Peoples swept down from the Black Sea and plundered the eastern Mediterranean. Before turning to Egypt, they made an alliance with Libyan tribes to the west, thus threatening the kingdom from two sides. Only after a long and costly war were the forces of the pharaoh Merneptah (thirteenth century B.C.) able to defeat the invaders. [Source: Gale Encyclopedia of World History: Governments, Thomson Gale, 2008]

In the eighth century B.C. the rulers of the African kingdom of Kush, a longtime rival to the south, took advantage of chaotic conditions to reunify Egypt under their command. The dynasty they created — the twenty-fifth, sometimes called the Ethiopian dynasty — was a prosperous one, but it was cut short by yet another invasion, this time by the Assyrians in 670 B.C. . It is a testament to the strength of the Egyptian economy and the allure of its culture that these invasions did not overwhelm native traditions or political structures. Successful invaders, such as the Kushites, left native institutions in place and adapted themselves to the new environment.

Around 525 B.C. the Persian emperor Cambyses II (d. 522 B.C.), continuing the expansionary campaigns of his father, Cyrus II (around 585–c. 529 B.C.), defeated the pharaoh Psamtik III (sixth century B.C.) and turned Egypt into a satrapy (province) of his empire. Persian satraps (governors) ruled until 404 B.C. ; historians often refer to this first period of Persian dominance as the Twenty-seventh Dynasty, because the satraps were careful to adopt the outer trappings of the pharaohs. After the death of the emperor Darius II Ochus (d. 404 B.C.), Persian efforts were directed elsewhere, and a successful rebellion led to a brief resurgence under the twenty-eighth, twenty-ninth, and thirtieth dynasties. In 343 B.C. the Persians again asserted their dominance, only to be defeated in turn by the Greek-speaking forces of Alexander the Great (356–323 B.C.). Amid great turmoil, one of Alexander’s generals, Ptolemy I (around 366–c. 283 B.C.), seized power, thus inaugurating the so-called Ptolemaic period. The Ptolemies were Greek speakers who became increasingly attached to Egyptian culture. The most famous Ptolemy is probably Cleopatra VII (69–30 B.C.), whose death coincided with the beginning of Roman rule.

Akhenaton’s unpopularity among his soldiers was probably due to his failure to go abroad on campaigns, as this deprived them of the chance for booty. Egypt’s military power was formidable, and its foreign possessions stretched from northern Sudan to northern Syria. Reverses, however, were common and sometimes catastrophic.

See Separate Articles: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MILITARY: SOLDIERS, ORGANIZATION, UNITS, MERCENARIES africame.factsanddetails.com ; ANCIENT EGYPTIAN WEAPONS, CHARIOTS, FIGHTING BOATS AND FORTRESSES africame.factsanddetails.com ; ANCIENT EGYPT'S RELATIONS WITH OTHER STATES africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Qadesh 1300 BC: Clash of the Warrior Kings” (1993) by Mark Healy Amazon.com;

“Battles of the Ancient World 1285 BC - AD 451: From Kadesh to Catalaunian Field”

by Kelly Devries (2011) Amazon.com;

“On Ancient Warfare: Perspectives on Aspects of War in Antiquity 4000 BC to AD 637"

by Richard A Gabriel (2018) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Warfare: Tactics, Weaponry and Ideology of the Pharaohs” by Ian Shaw Amazon.com;

“Warfare in Ancient Egypt” by Bridget McDermott (2004) Amazon.com;

“Warfare and Weaponry in Dynastic Egypt” by Rebecca Angharad Dean (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Fortifications of Ancient Egypt 3000–1780 BC” by Carola Vogel and Brian Delf (2010) Amazon.com;

“War & Trade with the Pharaohs: An Archaeological Study of Ancient Egypt's Foreign Relations” by Garry J. Shaw (2020) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun's Armies” by John Coleman Darnell (2007) Amazon.com; history at time

“Warfare in New Kingdom Egypt” by Paul Elliott (2017) Amazon.com;

“War in Ancient Egypt: The New Kingdom” by Anthony J. Spalinger (2008) Amazon.com;

“Bronze Age War Chariots” Illustrated (2006) by Nic Fields Amazon.com;

“Chariots in Ancient Egypt: The Tano Chariot, A Case Study”

by Dr. Andre J. Veldmeijer and Prof. Dr. Salima Ikram (2018) Amazon.com;

“Saite Forts in Egypt: Political-Military History of the Saite Dynasty”

by Květa Smoláriková (2008) Amazon.com;

“Warships of the Ancient World: 3000–500 BC” by Adrian K. Wood, Giuseppe Rava (Illustrator) (2013) Amazon.com;

Egypt Becomes More Militaristic in the New Kingdom

The Ancient Egyptians became more militaristic in the New Kingdom. The army had been trained in the war against the Hyksos, and the nobles had imbibed a taste for fighting; the political conditions also of the neighbouring northern countries at that time were such that they could not just then make any very serious opposition; consequently the Egyptians began to act on the offensive in Syria. At the same time it was a very different thing to carry on war with the civilised Syrians instead of with the or Lybians, and in place of the old raids for the capture of slaves, the driving off of cattle, and the devastation of fields, we find regular warfare. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Strategies were developed. Thutmose III tells us the story of his great expedition in full detail; for instance, where his forefathers would have used high-flown language about the annihilation of the barbarians, he speaks of the various routes that lead over Mount Carmel. The tone of the tomb-inscriptions of these kings seems to us most un-Egyptian and strange — they speak of war, not as a necessary evil, but as the highest good for the country. In the official reports of this period, which enumerate the military expeditions of these kings, the “first expedition “is spoken of before a second has taken place, as if there were no doubt that each monarch would take the field several times.

Amongst the kings of the 19th dynasty this view had become such an accepted fact, that delight in fighting was considered as great a virtue in a ruler as reverence for i. mon. When it was announced to the king that the “chiefs of the tribes of the Libyans “had banded themselves together to despise the “laws of the palace, his Majesty then rejoiced thereat. For the good god exults when he begins the fight, he is joyful when he has to cross the frontier, and is content when he sees blood. He cuts off the heads of his enemies, and an hour of fighting gives him more delight than a day of pleasure."

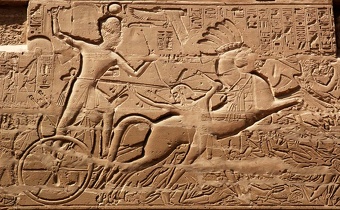

The Pharaoh in person now commanded in battle, and the temple pictures continually represent him in the thickest of the fight. Like his soldiers, he lays aside all his clothing, even to his loincloth and the front flap of his skirt; in a leathern case in his chariot he has his short darts, which he hurls against the enemy, while from his great bow he sends out arrow after arrow amongst them. He even takes part in the hand-to-hand fight, and his dagger and sickle-shaped sword are close at hand. In fact, if we may trust these representations of battle scenes, the king was indeed the only warrior who, with the reins of his horses tied round his body, and without even a chariot-driver, broke through the ranks of the enemy; we may surmise however that this was but a flattering exaggeration on the part of the sculptor in which even the poets scarcely ventured to join. "

Hyksos Invade Ancient Egypt

Around 1700 B.C., the Hyksos — a mysterious Semitic tribe from Caucasia in the northeast — invaded Egypt from Canaan and routed the Egyptians. The Hyksos were a chariot people. They and the Hittites were the first people to use chariots in the Middle East, an advancement that gave them an advantage over the people they conquered. The Hyksos introduced the horse and chariot to the Egyptians, who later used them to expand their empire. In Egyptian the word Hyksos means “ruler of foreign lands”.

Hyksos rule over Egypt was relatively brief. They established themselves for a while in Memphis and exactly how they came to power is not clear. Later they established a capital in Avaris, along the Mediterranean in the Nile Delta. During the Second Intermediate Period they ruled northern Egypt while Thebes-based Egyptians ruled southern Egypt. In the 2nd Intermediate Period, the four rulers during 15 and 16 dynasties were Hyksos. The Hyksos were thrown out of Egypt in 1567 B.C.

The Hyksos are sometimes referred to as the Shepherd Kings or Desert Princes. In the A.D. 1st century The Roman-Jewish historian Josephus described the Hyksos as sacrilegious invaders who despoiled the land. One ancient text on the Hyksos reads: “Hear ye all people and the folk as many as they may be, I have done these things through the counsel of my heart. I have not slept forgetfully, (but) I have restored that which has been ruined. I have raise up that which has gone to pieces formerly, since the Asiatics were in the midst of Avaris of the Northland, and vagabonds were in the midst of them, overthrowing that which had been made. They ruled without Re, and he did not act by divine command down to (the reign of) my majesty. (Now) I am established upon the thrones of Re....” [Source: James B. Pritchard, “Ancient Near Eastern Texts,” Princeton, 1969, web.archive.org, p. 231]

Chronicles that portray Hyksos rule as cruel and repressive were probably Egyptian propaganda. More likely they came to power within the existing system rather than conquering it and ruled by respecting the local culture and keeping political and administrative systems intact. Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “The Hyksos presented themselves as Egyptian kings and appear to have been accepted as such. They tolerated other lines of kings within the country, both those of the 17th dynasty and the various minor Hyksos who made up the 16th dynasty.” [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

“The Hyksos brought many innovations to the Egyptians: looms, new methods of bronze working, irrigation and pottery as well as new musical instruments and musical styles. New breeds of animals and crops were introduced. But the most important changes were in the area of warfare; composite bows, new types of daggers and scimitars, and above all the horse and chariot were all introduced by the Hyksos. It has been said that the Hyksos modernized Egypt and ultimately the Egyptians themselves benefited from their rule. [Sources: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com, Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

19th century view of the Hyksos invasion

Military Campaigns of Thutmose III

In a 19 year period of his rule Thutmose III (ruled 1479-1425) led military campaigns at a rate of almost one a year, including a victory over the Canaanites at Megiddo in present-day Israel. There are lengthy descriptions of his battles on the rock walls of Karnak. They include tales of soldiers hiding in baskets delivered to enemy cities and boats hauled 250 miles overland for a surprise attack. In the reliefs Thutmose himself is depicted as a sphinx trampling Nubians and a warrior smiting an Asiatic lion.

One of Thutmose’s greatest military victory occurred in Joppa (present-day Jaffa, Israel) in 1450 B.C. According to a rare papyrus text, the Egyptians secured victory after employing Trojan-horse-like deception. After the city failed to fall during a siege, the commanding general Djehuty sent baskets to the city that were said to contain plundered goods. At night Egyptian soldiers emerged from the baskets and opened the city gates.

Thutmose III drive towards the Euphrates claimed new lands for Egypt and brought in tributes. Wall paintings from the period show Babylonians, Syrians, Nubians and Canaanites offering presents to the pharaoh and bowing in subservient positions. The military campaign is also blamed for triggering a series of conflicts that would ultimately would deal the Egyptians a costly defeat at the hands of the Assyrians.

See Separate Article: THUTMOSE III (1480-1426 B.C.): ANCIENT EGYPT’S GREATEST RULER? africame.factsanddetails.com

Battle of Kadesh

Some regard the Battle of Kadesh as the first true battle. Ramses II desired northern Syria because of vital routes linking the Caucasus and Anatolia with Mesopotamia. The region was controlled by the Hittites, whose power and prosperity was mostly dependent on control of these routes and metal sources. Although Ramses II inscriptions proclaim victory at the key battle of Kadesh (Qadesh), it seems more likely that Ramses was turned back by the Hittite king Muwatalli. Many historians view the battle at Kadesh as a disaster for the Egyptians — a near defeat caused poor military intelligence on the part of the Egyptians and salvaged only with the help of last-minute arrival of reinforcements from the Lebanese coast. In Ramses II' accounts of the event, which, cover entire walls of some of his monuments, the battle was a dramatic and glorious Egyptian victory achieved single-handedly by Ramses himself. This battle took place in the 5th year of Ramses (c 1275 B.C. by the most commonly used chronology).” [Source: Crystal Links]

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “As was usual in those days, the threat of foreign aggression against Egypt was always at its greatest on the ascension of a new Pharaoh. Subject kings no doubt saw it as their duty to test the resolve of a new king in Egypt. Likewise, it was incumbent on the new Pharaoh it make a display of force if he was to keep the peace during his reign.” [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

“On his second campaign against the Hittites, Ramses found got himself in trouble attacking “the deceitful city of Kadesh”. “He had divided his army into four sections: the Amun, Ra, Ptah and Setekh divisions. Ramses himself was in the vanguard, leading the Amon division with the Ra division about a mile and a half behind. He had decided to camp outside the city – but unknown to him, the Hittite army was hidden and waiting. They attacked and routed the Ra division as it was crossing a ford. With the chariots of the Hittites in pursuit, Ra fled in disorder – spreading panic as they went. They ran straight into the unsuspecting Amun division. With half his army in flight, Ramses found himself alone. With only his bodyguard to assist him, he was surrounded by two thousand five hundred Hittite chariots. ^^^

See Separate Article: RAMSES II, THE HITTITES AND THE BATTLE OF KADESH africame.factsanddetails.com

Wars During the Reign of Ramses III

Pierre Grandet wrote: “Ramesses III fought three wars, all of them defensive campaigns against attempted invasions of Egypt: in year five, against the Libyans; in year eight, against the “Peoples of the Sea”; and in year eleven, against a second Libyan wave. The rapid succession of these attempts, the interaction between their actors, and their chronological connection to the destruction of Hatti and of other states in the ancient Near East generally lead to the conclusion that they were caused by some common factor, or factors, that have yet to be clearly identified. [Source: Pierre Grandet, 2014, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

The Sea Peoples annihilated the Hittite Empire and looked they might do the same to the Egyptians. The Great Harris Papyrus, the longest know papyrus, describes how many people throughout the region were made homeless. ‘The foreign countries plotted on their Islands and the people were scattered by battle all at one time and no land could stand before their arms.’

The Sea Peoples were well armed and desperate. Mark Millmore wrote in iscoveringegypt.com: “The Sea Peoples were on the move. They had, by now, desolated much of the Late Bronze Age civilizations and were ready to make a move on Egypt. A vast horde was marching south with a huge fleet at sea supporting the progress on land. To counter this threat Ramses acted quickly. He established a defensive line in Southern Palestine and requisitioned every available ship to secure the mouth of the Nile. Dispatches were sent to frontier posts with orders to stand firm until the main army could be brought into action. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

See Separate Article: RAMSES III (1195 – 1164 B.C.): THE LAST GREAT PHARAOH africame.factsanddetails.com

Defeat of the Sea People

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024