Home | Category: Government, Military and Justice

BUREAUCRACY IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Egyptians had an efficient bureaucracy which collected taxes to finance grand projects. Even low bureaucrats sometimes viewed themselves as big shots. In Egypt a national bureaucracy supervised the construction of canals and monuments and pyramids by 2700 B.C.

The Egyptians were very bureaucratic. They liked to make records and lists. Only a handful of which have made it to modern times because they were written on papyrus. It has been suggested that the Egyptians affinity with bureaucracy was linked to reverence of the past and need to preserve it. Officials called “viziers” helped the king govern. The viziers acted as mayors, tax collectors, and judges. Other high officials who served the king included a treasurer and an army commander.

Sometimes the titles of an official offer no hint of what he actually does. t If we read the long list of titles in the tomb of Un'e the prince, the administrator of the south, the chief reciter-priest, the nearest friend of the king, the leader of great men, the sub-director of the prophets of the pyramids of King Pepi I, the director of the treasure-houses, the scribe of the drinks, the superintendent of the two fields of sacrifice," etc., we should never realise that this was the man of whom we read in another inscription, that his duties were to order stone to be cut for the pyramid of the king and to examine all the state property. Still less should we guess that in his youth Unas officiated as a judge, and that later he commanded the Egyptian army in a dangerous war. His titles in no way indicate what were the most famous achievements of his life, and meanwhile others who bear the title of “Commander of the soldiers “may never have been in action. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

A number of tombs of ancient Egyptian government officials have been unearthed. In March 2024, archaeologists announced the discovery of a tomb of Seneb-Neb-Af, a palace official in charge of the “administration of tenants,” and his wife Idet the “Priestess of Hathor and Lady of the Sycamore.” Archaeologists said the tomb dates to around 2300 B.C. and was decorated with colorful scenes of people herding donkeys and several people in a procession carrying a bird and other objects, possibly offerings. The tomb is located in The Dahshur archaeological site about 25 miles south of Cairo, in an area that was part of the ancient Memphis. See ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TOMB PAINTINGS factsanddetails.com [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, March 22, 2024]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

"The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom: The Highest Titles and Their Holders" by Naguib Kanawati and Nigel Strudwick Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Administration (Handbook of Oriental Studies: Section 1; The Near and Middle East) by Juan Carlos Moreno García (2013) Amazon.com;

“Local Elites and Central Power in Egypt during the New Kingdom”

by Marcella Trapani Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Society” by Danielle Candelora, Nadia Ben-Marzouk, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“State in Ancient Egypt, The: Power, Challenges and Dynamics” by Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia (2019) Amazon.com;

“Court Officials of the Egyptian Middle Kingdom” by Wolfram Grajetzki (2009)

Amazon.com;

“Akhenaten's Royal Court: The City at Amarna and Its Officials” by David W Pepper (2022) Amazon.com;

”Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians: Volume 1: Including their Private Life, Government, Laws, Art, Manufactures, Religion, and Early History (Cambridge Library Collection - Egyptology) by John Gardner Wilkinson (1797–1875) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization” by Barry Kemp (1989, 2018) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt and Early China: State, Society, and Culture” by Anthony J. Barbieri-Low and Marissa A. Stevens (2021) Amazon.com

Structure of the Ancient Egyptian Bureaucracy

Above the scribes and the superintendent of the scribes, stood a chief, and between the prophets and their superintendent were the subsuperintendents and the deputy superintendents. Then there were “first men," “chiefs. "“great men," “associates," as well as other dignitaries. There was wide scope for the ambition of the Egyptian official, who, if he longed for them, could always obtain high-sounding titles; there was such as the splendid title “Chief of the secrets," or, as we should say, of the privy council. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

There were privy councillors connected with all branches of the government. The officers of the palace became “privy councillors of the honourable house," ° the judges became “privy councillors of the secret words of the court of justice," “and the chiefs of the provinces became “privy councillors of the royal commands. " '" Me who directed the royal buildings was called “privy councillor of all royal works. " '' A general was the “privy councillor of all barbarian countries," and the high priest of Heliopolis, who also officiated as astrologer, was even called the “privy councillor of the heavens. " '' These titles were so meaningless that the Egyptians generally contented themselves with the first half of them, such as they would say “Chief of the secrets “in the same way as we should abbreviate our titles of privy councillor of the kingdom or of the admiralty, into privy councillor alone.

From what we have said, it will be seen that the structure of the old Egyptian kingdom was somewhat lax. As long as the royal power was strong, the princes of the provinces, the so-called nomarchs, were officials governing under the guidance of the court, the center of government. As soon as this central power became weaker the nomarchs began to feel themselves independent rulers, and to consider their province as a small state belonging to their house. An external circumstance — the places they chose for their tombs, indicates whether a race of nomarchs considered themselves as officials or princes.

Family Served as Social Safety Net in Ancient Egypt

Anne Austin wrote in The Conversation: In cases where these provisions from the state were not enough, the residents of Deir el-Medina turned to each other. Personal letters from the site indicate that family members were expected to take care of each other by providing clothing and food, especially when a relative was sick. These documents show us that caretaking was a reciprocal relationship between direct family members, regardless of gender or age. Children were expected to take care of both parents just as parents were expected to take care of all of their children. [Source:Anne Austin, Assistant Teaching Professor, University of Missouri-St. Louis, The Conversation, May 3, 2021]

“When family members neglected these responsibilities, there were fiscal and social consequences. In her will, the villager Naunakhte indicates that even though she was a dedicated mother to all of her children, four of them abandoned her in her old age. She admonishes them and disinherits them from her will, punishing them financially, but also shaming them in a public document made in front of the most senior members of the Deir el-Medina community.

“This shows us that health care at Deir el-Medina was a system with overlying networks of care provided through the state and the community. While workmen counted on the state for paid sick leave, a physician, and even medical ingredients, they were equally dependent on their loved ones for the care necessary to thrive in ancient Egypt.

RELATED ARTICLES: HEALTH CARE IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

Ancient Egyptian Scribes

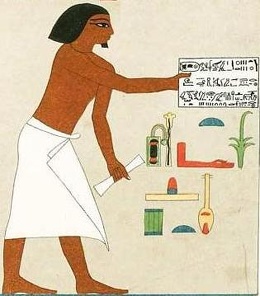

Many people that performed bureaucratic duties in ancient Egypt were scribes. Being a scribe in ancient Egypt was a high-status position in ancient Egypt, especially since only 1 percent to 5 percent of the ancient Egyptian population could read and write, according to the University College London. The ancient Egyptians believed that writing was invented by the ibis headed god Thoth and that words had magical powers.

"Officials with scribal skills belonged to the elite of the time and formed the backbone of the state administration," Veronika Dulíková, an Egyptologist at the Czech Institute of Egyptology of the Faculty of Arts at Charles University, in the Czech Republic, told Live Science. "They were therefore important for the functioning and management of the whole country. "[Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, June 28, 2024]

Scribes belonged to a caste. When students were being taught by the fathers they practiced their hieroglyphics on stones and potsherds before they wrote on papyrus. Describing the importance of the profession one ancient Egyptian poet wrote: "It's the greatest of all calling/ Thee is none like it in the land/Set your heart on books!/...There's nothing better than books!" "See, there's no profession without a boss/ Except for the scribe ; he is the boss." [Source: David Roberts, National Geographic, January 1995]

One papyrus, translated by Miriam Lichtheim, says, ''Happy is the heart of him who writes; he is young each day ... Be a scribe! Your body will be sleek, your hand will be soft ... You are one who sits grandly in your house; your servants answer speedily; beer is poured copiously; all who see you rejoice in good cheer.''

See Separate Article: SCRIBES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Duties of Scribes in Bureaucracy

The scribe engaged in duties such “to be copied “or “to be kept in the archives of the governor. " The documents were then given into the care of the chief librarian of the department they concerned, and he placed them in large vases and catalogued them carefully. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Position, power, and riches could not indeed be won even by the most diligent, unless his superior, “his lord," as the Egyptians said, was pleased to bestow them upon him. The scribe was therefore obliged before all things to try and stand well with his chief, and for this purpose he followed the recipe, which has been in use during all ages: “Bend thy back before thy chief," taught the wise Ptahhotep of old, and the Egyptian officials conscientiously followed this maxim. Submission and humility towards their superior officers became second nature to them, and was expressed in all the formulas of official letter-writing. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Whilst the chief writes to his subordinates in the most abrupt manner: “Do this or that, when you receive my letter," and rarely omits to add admonitions and threats, the subordinate bows down before him in humility. He docs not dare to speak directly to him, and only ventures to write “in order to rejoice the heart of his master, that his master may know that he has fulfilled all the commissions with which he was intrusted, so that his master may have no cause to blame him. " No one was excepted from writing in this style; the scribe 'Ennana writes thus to “his master Oagabu, the scribe of the house of silver," and in the same way he assures “PaRaemheb the superintendent of the house of silver “of his respect. lcsides this official correspondence, personal submission and affection are also often expressed towards a superior, and a grateful young subordinate sends the following lines to his chief: ““I am as a horse pawing the ground; My heart awakes by day, And my eyes by night, For I desire to serve my master, As a slave who serves his master. '"

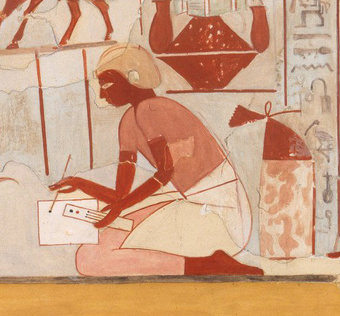

Posture of Scribes So Bad It Disfigured Their Skeletons

Ancient Egyptian scribes worked in hunched over positions that were so extreme, appears to have caused them to develop osteoarthritis in their joints and other skeletal issues — a finding based on an analysis of 69 adult male skeletons — 30 of whom were scribes — who were buried between 2700 and 2180 B.C. in a necropolis in Abusir published June 27, 2024 in the journal Scientific Reports. [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, June 28, 2024]

Scribes often performed repetitive administrative tasks that involved sitting in certain positions for prolonged periods of time, according to a statement. Jennifer Nalewicki wrote in Live Science: Researchers noticed that the scribes' skeletons showed more obvious degenerative changes in their joints, compared to the adult males who held other occupations. The areas most affected included the right collarbone, the right upper arm bone where it connects with the shoulder socket, the bottom of the right thigh bone where it meets the knee and the vertebra at the top of the spine.

The researchers also noticed unique indentations in both kneecaps of each scribe, and a "flattened surface on a bone in the lower part of the right ankle," according to the statement. The cause of these skeletal changes was likely due to scribes sitting for long periods in a cross-legged position or while kneeling on their left legs with their right legs bent upwards with the papyrus in their laps. And — much like today's office workers — the scribes hunched over as they wrote.

"In a typical scribe's working position, the head had to be bent forward and the spine flexed, which changed the center of gravity of the head and put stress on the spine," lead author Petra Brukner Havelková, an anthropologist in the Department of Anthropology at the National Museum in Prague, told Live Science. "And the correlation between [jaw disorders] and cervical spine dysfunction or neck/shoulder symptoms is well documented or supported by clinical studies. " She added, "We may realize that although they were high-ranking dignitaries who belonged to the ancient Egyptian elite, they suffered the same worries as we do today and were exposed to similar occupational risk factors in their profession as most civil servants today. "

There have also been numerous statues and wall art found in tombs showing scribes sitting in these exact positions performing their tasks. "The relief decoration in tombs and scribal statues give us an idea of the postures of the scribes of the time," Dulíková said. "They were in different sitting and standing positions. These are therefore very important for studying the physical changes involved. " The scribes' jaws and first bones in their right thumbs also appeared to be affected, bearing wear-and-tear not seen in the other skeletons. This was likely the result of the scribes chewing the ends of rush stems to create writing utensils, which they then pinched with their thumbs as they wrote. "Our research reveals that remaining in a cross-legged sitting or kneeling position for extended periods, and the repetitive tasks related to writing and the adjusting of the rush pens during scribal activity, caused the extreme overloading of the jaw, neck and shoulder regions," the authors wrote in the study.

Pity the Poor Ancient Egyptian Official in a Far-Away Post

Manifold were the small troubles which had to be endured by the official in his career. A certain official trusting in the fact that his superior was a “servant of Pharaoh, standing below his feet," such as living at the court, ventured to depart a little from the instructions he had received touching a distant field in the provinces and when he did he could be harshly punished

A scribe had not only to fear severity from those above him, but also annoyances from his colleagues and his comrades. Each high official watched jealously that no one should meddle with his business, and that the lower officials should give up their accounts and the work of the serfs to him and not to one of his colleagues. He was always ready to regard small encroachments on his rights as criminal deviations from the good old customs, and to denounce them as such to the higher powers, and when not able to do this, he vexed his rival in every way that he could,

Another misfortune which could always befall an official was to be sent to a bad locality. There were such in Egypt, and those who had to live in the oases or in the swamps of the Delta had good right to complain. A letter has come down to us written by one of these unfortunate scribes to his superior; he was stationed in a place otherwise unknown to us — Oenqcn-taue, which he said was bad in every respect. If he wished to build, “there was no one to mould bricks, and there was no straw in the neighbourhood. " What was he to do under these circumstances? "I spend my time," he complains, “in looking at what there is in the sky { such as the birds), I fish, my eye watches the road . . . I lie down under the palms, whose fruit is uneatable. Where are their dates? They bear none! “Otherwise also the food was bad; the best drink to be got was beer from Qede.

Two things there were indeed in plenty in Oenqen-taue: flies and dogs. According to the scribe there were 500 dogs there, 300 wolf-hounds and 200 others; every day they came to the door of his house to accompany him on his walks. These were rather too many for him, though he was fond of two, so much so that, for want of other material to write about, he describes them fully in his letter. One was the little wolf-hound belonging to one of his colleagues; he ran in front of him barking when he went out. The other was a red dog of the same breed with an exceptionally long tail; he prowled round the stables at night. The scribe had not much other news to give from Oenqen-taue, except the account of the illness of one of his colleagues. Each muscle of his face twitches. “He has the Uashat'ete illness in his eyes. The worm bites his tooth. " This might be in consequence of the bad climate.

Another scribe, a native of Memphis, writes how much he suffers from ennui and home-sickness in his present station; his heart leaves his body, it travels up-stream to his home. “I sit still," he writes, “while my heart hastens away, in order to find out how things are in Memphis. I can do no work. My heart throbs. Come to me Ptah, and lead me to Memphis, let me but see it from afar. " He was indeed considered fortunate who escaped these unpleasant experiences, and remained at home, or was sent to the same station with his father; his friends all congratulated him. Thus Seramun, the chief of the mercenaries and of the foreigners, writes to Pahripedt, the chief of the mercenaries, who has been sent to the same place in the Syrian desert where his father was already stationed: “I have received the news you wrote to me: the Pharaoh, my good lord, has shown me his good pleasure; 'the Pharaoh has appointed me to command the mercenaries of this oasis. ' Thus didst thou write to me. Owing to the good providence of Ra, thou art now in the same place with thy father. Ah! bravo! bravo! I rejoiced exceedingly when I read th\letter. May it please Ra Harmachis that thou shouldst long dwell in the place with thy father. May the Pharaoh do to thee according to thy desire.

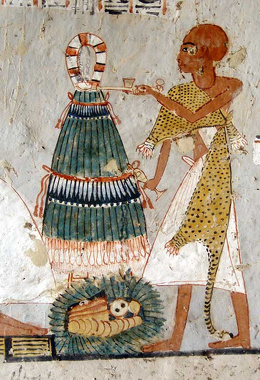

Priests in Ancient Egypt

Priests also performed bureaucratic duties and temples supplied many government-like services. Priests linked with temples were the next most important class of people in ancient Egypt after the king. They too were sometimes regarded as gods. In the Late and Middle Kingdoms priests were selected by the pharaoh. By the New Kingdom there was a priestly class. Powerful priesthoods were based in Memphis and Thebes.

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “New Kingdom sources provide more clues about the internal functioning of temples, including information on the social background of priests and on the conflicts of interest that took place among them. The organization of the nascent New Kingdom monarchy relied heavily on the integration of local elites through the mediation of temples, especially during its earliest steps, following the expulsion of the Hyksos. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

Sataimau of Edfu, for instance, was a scribe and priest who served at the temple of Edfu in the reign of Ahmose, the first king of Dynasty 18. He was, in fact, from an elite family closely connected to the monarchy and achieved career advancement with successive appointments to two significant posts in the temple. These were remunerated with part of the offerings presented to the sanctuary and with the income derived from the cult of a royal statue, including about 40 hectares of land (one hectare being roughly equivalent to 2.5 acres).

See Separate Article: PRIESTS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

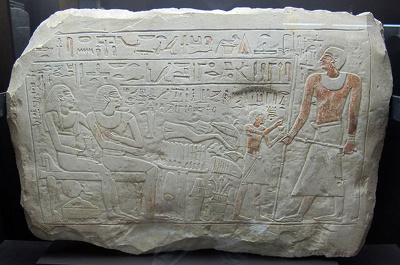

Treasury Officials in Ancient Egypt

The treasury department was arguably the most important bureaucratic office in ancient Egypt. At the head of it was a high official who called himself with bold exaggeration, the “governor of all that exists, or that does not exist. " At the king's command he gave out of his treasury, sacrifices for the gods and sacrifices for the deceased, and it was he who “fed the people," such as he gave to the state officials their salaries in bread and meat. Even during the Old Kingdom the position of the lord high treasurer was a very high one, and in later times his influence was, if possible, still greater; he is entitled such as “the greatest of the great, the chief of the courtiers, the prince of mankind; he gives counsel to the king, all fear him, and the whole country renders account to him. " One is mentioned as the “captain of the whole country, the chief of the north country," and another the “chief commander of the army. " Yet, notwithstanding their high rank, they performed the duties of their office in person; we meet with one in the quarries of Sinai, another journeying to Arabia, and another on his way to the Nubian gold mines. It was incumbent on them personally to endow one of the great temples at home with the precious things they brought from foreign countries. ' [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The second official of the treasury, the “treasurer of the god," whose chief business consisted in the supervision of the transport of precious things, is to be met with in the mines,' in Nubia, or on the way to Arabia. ' He is still the “conductor of the ships," and the “director of the works," but his title has been changed to correspond with the spirit of these times, in which the hierarchy of the bureaucracy was more emphasised than during the Old Kingdom; he is therefore called in the first place the “cabinet minister of the hall of the treasurer," or the “cabinet minister (or “chief cabinet minister") of the house of silver," ' at the same time he retains his old title, but only as a title, not as designating his office. The “cabinet minister “also held a high place at court; one boasts that “he had caused truth to ascend to his master, and had shown him the needs of the two countries," and another relates that he had “caused the courtiers to ascend to the king. " The titles of the lower treasury officials were also changed, and instead of using their old designation of c treasurer, they preferred the more fashionable one of "assistant to the superintendent of the treasurer."

We have already seen that many of the chief treasurers claim by their titles to be the highest official in the state. As such however we must generally regard the “governor and chief judge"; he may of course at the same time be the “chief treasurer. " Frequently during the Middle Kingdom this “chief of chiefs, director of governors, and governor of counsellors, the governor of Horus at his appearing," receives the government of the capital town; ' in later times this becomes the rule.

Documents from the House of Silver

Numerous documents have come down to us, showing how the accounts were kept in the department of the “house of silver," and in similar departments; the translation of these is however extremely difficult, owing to the number of unknown words and the abbreviations they contain. These documents show exactly how much was received, from whom and when it came in, and the details of how it was used. This minute care is not only taken in the case of large amounts, but even the smallest quantities of grain or dates are conscientiously entered. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Nothing was done under the Egyptian government without documents: lists and protocols were indispensable even in the simplest matters of business. This mania for writing (we can designate it by no other term) is not a characteristic of the later period only; doubtless under the Old and the Middle Kingdom the scribes wrote as diligently as during the New Kingdom. The pictures in the old tombs testify to this fact, for whether the grain is measured out, or the cattle are led past, everywhere the scribes are present. They squat on the ground, with the deed box or the case for the papyrus rolls by them, a pen in reserve behind the ear, and the strip of papyrus on which they are writing, in their hands. Each estate has its own special bureau, where the sons of the proprietor often preside. We find the same state of things in the public offices: each judge is also entitled “chief scribe," and each chief judge is the "superintendent of the writing of the king "; one of the great men of the south is called

There were scribes who personally assisted the heads of the various departments, as such as the governor, the “prince “of a town, or the “superintendent of the house of silver "; '"' these officials doubtless often exercised great influence as the representatives for their masters. The monarch also always had his private secretary; during the Old Kingdom we find the “scribe in the presence of the king," “During the Middle Kingdom the “scribe witness in the presence of the king," and during the New Kingdom the "royal vassal and scribe of Pharaoh."

Tomb of Wahtye a high-ranking priest and official who served under King Neferirkare Kakai during the Fifth Dynasty of Egypt around 2500 BC

Rich Officials in Ancient Egypt

Owing to the power and to the gifts bestowed by the favor of the king, riches now began to make their appearance amongst the officials; and whoever could afford it, indulged in a beautiful villa, a fine carriage, a splendid boat, numerous Africans — as servants, and house officials — gardens and cattle, costly food, good wine, and rich clothing. The following example will give an idea of the riches which many Egyptian grandees gained in this way. It was an old custom in Egypt, which has lasted down to modern days, that on New Year's Day “the house should give gifts to its lord. " Representations in the tomb of a high official of the time of Amenhotep II (his name is unfortunately lost) show us the gifts he made to the king as a “New Year's present. " “There are carriages of silver and gold, statues of ivory and ebony, collarettes of all kinds, jewels, weapons, and works of art. " [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The statues represent the king and his ancestors, in various positions and robes, or in the form of sphinxes with the portrait head of the monarch. Amongst the weapons are axes, daggers, and all manner of shields, there are also coats of mail, several hundred leather quivers of various shapes, 680 shields of the skin of some rare animal, 30 clubs of ebony overlaid with gold and silver, 140 bronze daggers and 360 bronze sickle-shaped swords, 220 ivory whip-handles inlaid with ebony, etc. In addition, numerous vases of precious metal in curious Asiatic forms, two large carved pieces of ivory representing gazelles with flowers in their mouths, and finally there is a building overgrown with fantastic plants bearing gigantic flowers, amongst which tiny monkeys chase each other. This was probably part of a kind of service for the table in precious metal.

The splendid Theban tombs in which the chiefs of the bureaucracy of the New Kingdom rest, give us also the same idea of great riches. There were of course comparatively few of the officials who rose to such distinction; the greater number had to live on their salaries, which consisted as a rule of payment in kind — corn, bread, beer, geese, and various other necessaries of life, which are “registered in the name “of the respective official. '' We hear, however, of payments in copper also; a letter from Amenem'epct to his student I'aibasa assigns to the former 50 Uten (about four kilograms) of copper “for the needs of the serfs of the temple of Heliopolis. "

It seems, however, that the storehouses of ancient Egypt were scarcely better supplied than the coffers of the modern country; we have at any rate in the letters of that time many complaints of default of payment. A servant named Amenemu'e complains to the princes that “in spite of all promises no provisions are supplied in the temple in which I am, no bread is given to me, no geese are given to me. " A poor chief workman only receives his grain after he has "said daily for ten days ' Give it I pray. ' “The supplies might indeed often await the courtesy or the convenience of a colleague. “What shall I say to thee? “complains a scribe: “give ten geese to my people, yet thou dost not go to that white bird nor to that cool tank. Though thou hast not many scribes, yet thou hast very many servants. Why then is my request not granted? “'

To supplement his salary the official had often the use of certain property belonging to the crown. In this matter proceedings were very lax, and the widow of an official generally continued to use the property after her husband's death. In fact, in one case, when the mother of an official died, who had had the use of one of the royal carriages, the son tried to obtain permission from his chief, for his sister who had been left a widow a year before, to use the aforesaid carriage. Although his superior did not at once agree to the request, yet he did not directly refuse him; he told him that if he would visit him when on his journey, he would then see what he could do. There is the reverse side to this apparent generosity of the Egyptian government; it is evident that he who uses state property is bound to pay a certain percentage of what it enables him to earn; he only holds it in pledge.

Tomb of Ramses II’s Treasurer

A 3,200-year-old tomb was built for an official named Ptah-M-Wia at the ancient Egyptian necropolis of Saqqara, near Cairo. He was a senior official and economic minister in the 19th Dynasty during the reign of pharaoh Ramses II (r. ca. 1279–1213 B.C.). Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: Ptah-M-Wia was head of the treasury centuries before the invention of minted coins; at that time people made payments with goods, rations or precious metals. Ptah-M-Wia was in charge of making "divine offerings" at one of the temples built by Ramses II at Thebes. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, November 2, 2021]

Benjamin Leonard wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Like the adjacent burials of other officials of the period, the mudbrick tomb is laid out in the style of a temple, with an entranceway, two courtyards, and, at the western end, a chapel where funerary rites were performed. The plastered walls of one of the courtyards are decorated with paintings depicting the sacrifice of a bull and a procession of people bearing offerings. In the other courtyard, which contains Ptah-M-Wia’s as-yet-unopened burial shaft, excavators found seven square pillars inscribed with the djed symbol, which is associated with Osiris, the god of the underworld. [Source: Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology Magazine, March/April 2022]

Inscriptions on limestone blocks at the tomb’s entrance list the various titles Ptah-M-Wia held throughout his career. “He was the head of the treasury of the temple of Ramses II in Thebes,” says archaeologist Ola El Aguizy of Cairo University. “He was also the head of cattle and head of offerings to all the gods of Upper and Lower Egypt. ” It’s unclear how long Ptah-M-Wia lived, who his relatives were, and whether his tomb was built before or after those nearby. Says El Aguizy, “We have to uncover the rest of the tomb and go into the burial shaft to better understand his life and genealogy. ”

Tomb of the Ancient Egyptian Dignitary Who Read Top Secret Documents

In June 2022, a team of archaeologists in Egypt announced that they had discovered the 4,300-year-old tomb of a man named Mehtjetju, an official who claimed that he had access to "secret" royal documents. "The dignitary bore the name Mehtjetju and was, among other things, an official with access to royal sealed — that is secret — documents," according to the hieroglyphs on the tomb, Kamil Kuraszkiewicz, a professor at the University of Warsaw's faculty of Oriental Studies, said in a statement. Mehtjetju's tomb was found next to the Step Pyramid of Djoser, which was constructed about 4,700 years ago in Saqqara. Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: It's no coincidence that Mehtjetju's tomb is next to the Step Pyramid, the first pyramid built by the ancient Egyptians. Djoser "was an important and revered king from the glorious past," and officials sometimes wanted to be buried beside his pyramid, even centuries after Djoser died, Kuraszkiewicz told Live Science. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, July 1, 2022]

Mehtjetju lived sometime during the reign of the first three pharaohs of the sixth dynasty: Teti (reign ca. 2323 B.C. to 2291 B.C.), Userkare (reign ca. 2291 B.C. to 2289 B.C.) and Pepi I (reign ca. 2289 B.C. to 2255 B.C.). Mehtjetju would have served one or more of those pharaohs. His other titles included "inspector of the royal estate" and he was also a priest of the mortuary cult of the pharaoh Teti, according to the statement.

So far, archaeologists have excavated the façade (entrance) of the tomb's chapel, finding hieroglyphic inscriptions, paintings and a relief depicting Mehtjetju. No family members are mentioned in the hieroglyphic inscriptions, but the burial chamber has not been excavated yet and the tomb seems to be part of a larger complex that may hold his family's remains, Kuraszkiewicz told Live Science. Mehtjetju's high social status meant he could hire skilled artisans to build the tomb, according to the archaeologists, who said the façade's reliefs were crafted by a skilled hand. However, some of the tomb's rock is brittle and eroded, prompting conservators to intervene during the excavation.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo except Tomb of Ramses II’s Treasurer from Egyptian Ministry of Tourism & Antiquities

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024