Home | Category: Art and Architecture

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TOMB PAINTINGS

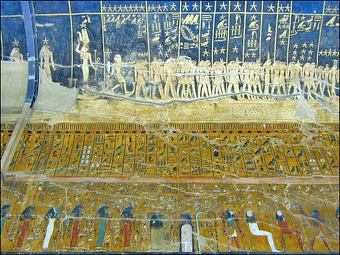

The wealthy were buried in elaborate tombs that were decorated with paintings from their lives and hieroglyphics that described their family, their achievements, offerings made at their funeral and a lists of feast days. Sometimes they featured battle scenes and scenes from everyday life like bread making, grain grinding and beer making.Tombs of kings, queens and nobles were typically decorated with murals with images of deities and people known to the deceased. Sometimes there were images of the daily lives of ordinary people. Images in tombs are often accompanied by texts from the “Book of the Dead” , which sometimes explain what is going on in the picture. Some of the greatest existing works of Egyptian art are the tomb paintings in the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens, particularly the tomb of Neferteri.

We are thankful to ancient Egyptian tombs and the ancient Egyptian belief that the afterlife was similar to life on earth and the deceased needed to bring things from their earthly life, including workers to perform chores, with them to the land of the dead. Artwork and grave goods that were entombed with the dead for these purposes has give us insights in the life of the ancient Egyptian and supplied us with wonderful works of art.

Tomb art includes depictions of ancient farmers working their fields and tending livestock, fishing and bird hunting, practicing carpentry, wearing costumes, and performing religious rituals and burial practices. "Many people think of the site as just a cemetery in the modern sense, but it's a lot more than that," Harvard University Egyptologist Peter Der Manuelian told National Geographic. "In these decorated tombs you have wonderful scenes of every aspect of life in ancient Egypt — so it's not just about how Egyptians died but how they lived. " Inscriptions and texts also allow research into Egyptian grammar and language. "Almost any subject you want to study about Pharaonic civilization is available on the tomb walls at Giza," Der Manuelian says. [Source: Brian Handwerk, National Geographic, December 21, 2023]

Heirakonpolis contains one of the oldest tomb painting. Created in 3200 B.C., it features stick-like figures. Some of the tombs there have been dated to 5000 B.C. Some tomb paintings date back to the Old Kingdom. In the wall painting with Egyptian hieroglyphics from Tomb 24, Giza there are lots of images of people wearing wraparound white linen skirts doing various activities, such as herding cattle, carrying tools, scribing, and worshiping.

RELATED ARTICLES:

PAINTING IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PERSPECTIVE, POSES, FLATNESS AND DIMENSIONS IN ANCIENT EGYPTIAN PAINTING africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Egyptian Tombs: The Culture of Life and Death” by Steven Snape (2011) Amazon.com;

“Cultural Expression in the Old Kingdom Elite Tomb” by Sasha Verma (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Tomb in Ancient Egypt” by Aidan Dodson, Salima Ikram (2008) Amazon.com;

“Foreigners in Ancient Egypt: Theban Tomb Paintings from the Early Eighteenth Dynasty” by Flora Brooke Anthony (2016) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Painting and Relief” by Gay Robins (2008) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Wall Paintings” by Francesco Tiradritti and Sandro Vannini (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Valley of the Kings: Tombs and Treasures of Egypt's Greatest Pharaohs” (1996) by C. N. Reeves, Richard H. Wilkinson, Nicholas Reeves, Amazon.com;

“The Treasures of the Valley of the Kings: Tombs and Temples of the Theban West Bank in Luxor” by Kent Weeks and Araldo De Luca (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings” by Richard H. Wilkinson and Kent R. Weeks Amazon.com;

“The Tomb of Queen Nefertari: Egyptian Gods and Goddesses of the New Kingdom” by Ruth Shilling (2020) Amazon.com;

“House of Eternity: The Tomb of Nefertari” by John McDonald (1996)

Amazon.com;

“In the Tomb of Nefertari: Conservation of the Wall Paintings” by Robert Steven Bianchi and John K. McDonald (1993) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife” by Erik Hornung and David Lorton (1999) Amazon.com;

“Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt” by John H Taylor (2001) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Art” Multilingual Edition by Salima Ikram (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Ancient Egypt: Revised Edition” by Gay Robins (2008) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Art” by Rose-Marie Hagen, Rainer Hagen, Norbert Wolf (2018) Amazon.com;

“Reading Egyptian Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Egyptian Painting and Sculpture”

by Richard H. Wilkinson (1994) Amazon.com;

“Principles of Egyptian Art” by H. Schafer and John Baines (1986) Amazon.com;

Images in Ancient Egyptian Tomb Paintings

According to the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago: “The Egyptians painted idealised scenes from daily life on the walls of their tombs: scenes of agricultural work such as harvesting crops, tending cattle and fishing, scenes of artisans at their work, including goldworkers and boat-builders and domestic scenes of banquets with musicians, dancers and guests. The scenes in the tomb represented the hoped for after-life, in which there were fertile fields and harmony and happiness at home; representing it in the tomb was thought to ensure an ideal existence in the next world.[Source: ABZU, University of Chicago Oriental Institute, oi-archive.uchicago.edu ]

Tombs typically contained: 1) images of the deceased performing tasks from everyday life or doing some great deed or achievement; 2) images of the deceased making offerings or sacrifices to Gods such as Anabus, Isis and Orissis; 3) images of cobras, gods with weapons or scorpions on their head intended to keep evil spirits from entering the tomb and protect the deceased; 4) images of deceased at the gates of the Nether World asking for permission to enter. To pass through each gate the deceased had to say the name of the gate and the god that guards it.

The deceased is often pictured proceeding on a journey to the nether world, on which he or she comes in contact with different gods and acquires their power and then caries their symbols with him or her. The ceilings of the tombs often feature a dark blue sky with thin, tightly-packed, five-pointed golden stars. There are often images of farmers, cooks, musicians, rowers — people who could carry out duties in the afterlife.

The head of the deceased is often pictured on the body of the bird Alba, whose duty it was to carry the soul of the dead to the Nether World. Maate, the winged Goddess of Justice and the winged serpent are often present, with her wings spread, on lintels over doorways in the tombs of pharaohs and their wives in the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens.

Painting in the Royal Tombs of Ancient Egypt

Royal tombs were supposed to be decorated entirely in relief en creux, but it is seldom that this system of work is found throughout, for if the Pharaoh died before the tomb was finished, his successor generally filled up the remaining spaces cheaply and quickly with painting. When the details of a figure are worked out by the modeller, this is evidently considered a great extravagance, and is often restricted to the chief figure in a representation. Thus, for instance, in the tomb of Seti I., the face of this king alone is modelled, while his body and all the other numerous figures are given in mere outline. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

On the art in Amenhotep II’s burial chamber in KV35 (Valley of the Kings Tomb No. 35), Maite Mascort wrote in National Geographic: A pillar, one of six dominating Amenhotep II’s burial chamber, is decorated with an image of the pharaoh receiving life from the god Osiris. The roof is decorated with stylized rows of stars, representing the night sky. Two rows of decorated pillars shows the pharaoh being received into the afterlife by the gods. Unlike other New Kingdom tombs, the art is confined to the burial chamber, and the color scheme is minimal. Historians consider the art in KV35 to be exemplary, undertaken by a highly accomplished artist. [Source: Maite Mascort, National Geographic, June 15, 2023]

Tomb of Seti I

The Tomb of Seti I is the largest and most decorated tomb in the Valley of the Kings. Known to scholars as KV17, its is extends 88 meters (290 feet) from entrance hall to burial chamber and goes on 173 meters (570 feet) further in what may be an attempt to construct a tunnel to the underworld. Ritual features in the tomb include a well chamber, and scenes from Egyptian funerary texts. One of these, from the Book of Gates, depicts the journey of a soul through the underworld.[Source: José Lull, National Geographic History, June 26, 2020]

José Lull wrote in National Geographic History: Not only are the tomb’s artworks breathtaking to see, they also provided today’s Egyptologists with the earliest, most complete set of funerary texts from ancient Egypt. Wall paintings depict detailed scenes from the Book of Amduat and texts from the Litany of Re, a collection of invocations and prayers to the solar deity. The giant sarcophagus is decorated with scenes from the Book of Gates — an Egyptian text that recounts the passage of a soul through the underworld — and is today regarded as one of the most important artifacts from Egypt’s 19th dynasty.

Extensive conservation efforts are being carries out to protect and preserve Seti’s tomb. In 2016 the Factum Foundation used the latest technology to scan and photograph the entire complex not only to preserve and study its artworks, but also to create high-precision facsimiles that can be printed to erect full-size models of the tomb in full color. Visitors can experience the majesty of a pharaoh’s resting place without endangering the original. The excavation of the tomb is largely complete, but its aura of enigma will linger, it seems, for centuries to come.

See Separate Article: FAMOUS TOMBS IN ANCIENT EGYPT'S VALLEY OF THE KINGS africame.factsanddetails.com

Tomb of Nefertari

The Tomb of Nefertari (in the Valley of the Queens near Luxor) is the most beautiful tomb in the Valley of the Queens or the Valley of the Kings and one of the most extraordinary works of art in the world. Over 3,200 year old, it is in amazingly good condition for its age and features extraordinary wall murals, painted with vivid colors, great skill and a wonderful sensitivity for detail.

Regarded as a close representation of the "House of Eternity," the tomb of Queen Nefertari is composed of seven chambers—a hall, side chambers and rooms connected by a staircase—and features paintings made on engraved outlines of humans, deities, animals, magic objects, scenes of everyday life and symbols such as ibis heads, scarabs, papyrus, lotuses, vultures and cobras.

On being inside the tomb, Marlise Simons wrote in the New York Times,"The effect is rich like a house hung with jewelry, and it has an intensity that appeals strongly to modern eyes. But what makes these galleries just as moving is the fine detail of the images, their exquisitely carved relief and the gestures of endearment that give the figures life...There is are sweetness and intimacy that makes contact across the centuries seem somehow possible."

See Separate Article: TOMB OF NEFERTARI: CHAMBERS, PAINTINGS, MEANING OF THE ART africame.factsanddetails.com

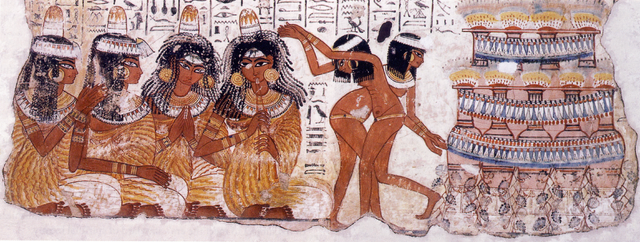

Tomb of Nebamun

The lost Tomb of Nebamun was an ancient Egyptian tomb from the 18th Dynasty located in the Theban Necropolis on the west bank of the Nile at Thebes (present-day Luxor). The tomb was the source of a number of famous decorated tomb scenes that are currently on display in the British Museum, London. Nebamun lived around 1350 B.C.. He was a middle-ranking official scribe and grain counter at the temple complex in Thebes.

Tomb of Nebamun tomb was discovered around 1820 by a young Greek, Giovanni ("Yanni") d'Athanasi. D'Athanasi and his workmen hacked out the pieces he wanted with knives, saws and crowbars. These were sold to the British Museum in 1821, D'Athanasi later died in poverty without ever revealing the tomb's exact location, which was not revealed at the time of its discovery in order to maintain secrecy during a period of competition between excavators, and was later lost. A scientific analysis in 2008-09 indicated the tomb's location in the vicinity of Dra' Abu el-Naga'. [Source Wikipedia]

The tomb's plastered walls were richly and skilfully decorated with lively fresco paintings, depicting idealised views of Nebamun's life and activities. The best-known of the tomb's paintings include Nebamun fowl hunting in the marshes, dancing girls at a banquet, and a pond in a garden. In 2009, the British Museum opened up a new gallery dedicated to the display of the restored eleven wall fragments from the tomb.[4][8] They have been described as the greatest paintings from ancient Egypt to have survived, and as one of the Museum's greatest treasures.

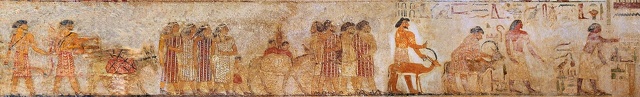

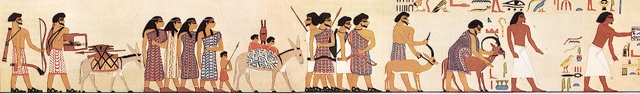

Paintings from Beni Hassan Tombs

Marley Brown wrote in Archaeology magazine: “The decorated tombs of Beni Hassan, a cemetery site on the east bank of the Nile in central Egypt, not only bear the stamp of the artisans who decorated them, but also reflect the lives lived by the deceased. The tombs date to the 11th and 12th Dynasties of Egypt’s Middle Kingdom (2050–1650 B.C.) and offer some of the best-preserved examples of how artists and tomb owners conceived of the natural world. Originally surveyed between 1893 and 1900 by Egyptologist Percy E. Newberry, they are now being reexamined by a team of researchers from Australia’s Macquarie University. According to project director Naguib Kanawati, the tombs at Beni Hassan are among the most complete and important of Middle Kingdom Egypt. The works depict a great range of fauna and flora, including species rarely seen in Egyptian art. They have proven especially revealing of the relationships Egyptians had with animals. [Source: Marley Brown, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2018]

The military capability of the region, governed by many of the interred, is a common theme. A painting of soldiers training and taking part in a naval siege appears in the tomb of an individual named Amenemhat. Many of the tombs at Beni Hassan include full-panel representations of animals in their natural habitats, including marsh and desert scenes that show a keen observation of animal behavior. “Sometimes they simply reflect everyday activities,” says Linda Evans, an Egyptologist and ethologist at Macquarie. “We see men driving herds of cattle, donkeys, sheep, and goats, which would have been a common sight in the surrounding fields. Other images show wild animals being hunted in the deserts or encountered in the marshes along the Nile. ”

“The degree of detail in the paintings can give the impression that they might be an accurate record of extant flora and fauna for the time in which they were produced. But according to Lydia Bashford, whose research at Macquarie focuses on birds in ancient Egyptian culture, the paintings are unlikely to be reliable as sources. “Investigations into tomb decoration and agency have shown that artists frequently replicated the content and scenes from contemporary tomb walls and those of earlier periods,” she says. Furthermore, she explains that certain animal species held significant cultural meaning, and so their images were often reproduced whether the animals were present or not.

“The team has surveyed 39 tombs from Beni Hassan’s upper section, all of which are cut into the limestone cliff face. Of those, 12 are embellished with artwork and belonged to government officials of the eastern Egyptian province called the Oryx nome. Paint made from ground minerals was sometimes applied directly to the limestone, or onto a finish made of gypsum plaster. Though the motifs of the Beni Hassan paintings are diverse, much of the subject matter depicted in them is similar from tomb to tomb, suggesting that specific scenes were considered an essential part of any memorial. “My gut feeling is that there were expectations that you would have certain images in your tomb,” says Evans. “They were a reflection of the tomb owner as a member of the king’s administration, and as somebody who was responsible for maintaining what the Egyptians called maat, which is the concept of balance in the universe. ”

“Taken as a whole, the tomb paintings have much to say about the variety of realms of ancient Egyptian existence and, at the same time, intimate some sense of an Egyptian cosmology. As Bashford puts it, “An image can be both what appears to us to be a scientific representation and simultaneously contain layers of symbolic meaning. ” Going forward, researchers using far more advanced techniques than were available to Newberry aim to study the architectural, artistic, and administrative developments of Middle Kingdom Egypt.

Images in Beni Hassan Tombs

Marley Brown wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Some panels depict events that officials were required to oversee every year, such as grain harvest and shipment to other parts of the kingdom. “These are standard scenes,” Evans says. “The deceased is telling the world, ‘Look, I’m a good guy, I did the right thing, I did what was expected of me. I helped the king maintain order by doing my job. ’” Some scenes were also intended to show off the power of the Oryx nome. The strength of the local army appears as a theme in the same location in three separate tombs in which the walls are divided into two sections: the upper showing many rows of wrestlers, presumably soldiers undergoing training, and the lower depicting the siege of a fortress and troops crowding onto boats. According to Melinda Hartwig, curator of Egyptian, Nubian, and ancient Near Eastern art at Emory University’s Michael around Carlos Museum, “In the Beni Hassan tombs, wrestling scenes are common and are found alongside battle scenes. These wrestling scenes depict all kinds of grips and holds that give us a window into ancient Egyptian sport, or, in these cases, more likely physical training for soldiers. ” [Source: Marley Brown, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2018]

“Differences in the content of the paintings across the site might reflect the individuality of tomb owners and the wide array of themes they wished to include. “No two scenes are exactly the same,” says Evans. “You have the artists bringing in their own idiosyncrasies, in terms of their choice of where to place certain images, and their abilities. ” Evans speculates that an artist might also have been told, “‘I would like you to include this,’ so long as it was not something that was wildly outside of decorum or expectations of what was supposed to be on their wall. ”

“Beni Hassan has yielded images of animals hardly ever seen in Egyptian art, such as bats, pigs, and an incredibly rare image of a pelican. The bird is shown in the process of taking flight and was found in the tomb of an official named Baqet II. Nearby, in the tomb of Baqet III, dozens of species of birds are depicted along with the Egyptian names for each, almost as though the deceased had been an avid bird watcher or amateur ornithologist. “The tomb of Baqet III comprises one of the most magnificent collections of ancient birds depicted in Egyptian art,” says Bashford.

Perhaps due to local worship of a feline goddess called “the scratcher,” the tombs at Beni Hassan have an abundance of cat images, including this one of a cheetah approaching a hedgehog. In one of the tomb paintings a hunter leads both a dog and a mongoose on leashes. The latter, a predator, likely has an allegorical role. An image of a falcon-headed canine is rare and thoroughly reflective of the symbolic approach often taken at Beni Hassan in its depictions of animals. This pelican beginning to take flight, unusual in Egyptian art, displays anatomical accuracy, and typifies the special attention paid to birds at the site.

Meaning of Images in Beni Hassan Tombs

The Beni Hassan tomb paintings, including this one belonging to an official named Khnumhotep II, depict a variety of themes relating to the lives of the deceased, and reflect their sense of the cosmos. Khnumhotep II is depicted in his tomb catching waterfowl in a net, which scholars say symbolizes the deceased exerting control over forces of chaos — often represented by birds in Egyptian art. Marley Brown wrote in Archaeology magazine: “It is important to note, according to Evans, that animal images often had a symbolic function, and potentially carried a deeper spiritual or magical meaning to the Egyptians. “The tomb was a very potent space in ancient Egypt,” she says, “so the paintings generally, and the animal images in particular, may have had multiple functions. ” [Source: Marley Brown, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2018]

“One theme that seems to run across many of the tombs at Beni Hassan as an allegory of sorts is the idea of the dominion of the local officials over forces of chaos or disorder. Evans says that hunting scenes, in particular, can be thought of in a similar way to images of local leaders upholding their commitment to the king. Ancient Egyptians, she explains, often saw birds as emblematic of problems such as societal disharmony or, especially, invasion by foreigners. Therefore, imagery such as that on display in the tomb of Khnumhotep II, which shows a hunter hauling in a net of water birds, can be read as symbolic of victory over the potential calamities they represent. In another example, perhaps the only one of its kind in Egyptian art, a hunter leads a mongoose on a leash. While the tombs at Beni Hassan are replete with scenes in which hunters are shown with dogs, the leashed mongoose serves as a potent metaphor. “If you look at all of the scenes of the river marsh areas, they are always full of life,” Evans explains. “You’ve got birds above the thicket. You can see hippos, fish, and crocodiles underwater. They appear to be simply a celebration of nature. But when I saw the leashed mongoose, I suddenly thought I’d been misreading them. The tomb owner is actually showing his ability to use these as hunting tools, to kill birds, the symbols of chaos. The mongoose is acting on the side of maat. ”

“Ancient Egyptian deities were often represented as animals and this too is on display at Beni Hassan. According to Evans, local people worshipped a cat goddess called Pakhet, meaning “the scratcher. ” Therefore, many of the depictions of cats in the cemetery complex likely had spiritual significance. “There are many images of cats at the site, including leopards, lions, caracals, servals, and African wildcats,” she says. These images are likely also significant because it is not until the Middle Kingdom that the first evidence of domestic cats begins to appear in tomb scenes.

“Elsewhere, in the tomb of an individual known as Khety, researchers have found one of the most arresting images at Beni Hassan — a four-legged creature with the head of a bird. It has been the source of much scholarly discussion since Newberry first recorded it. “The Middle Kingdom tomb paintings at Beni Hassan cover almost two centuries,” says Hartwig, “and give specific details about birds, dogs, and human activities. In the artists’ attempts to reproduce many types of animal life, they also included composite creatures, like the falcon-headed canine, which was probably derived from myth. ” The Egyptians often used this type of imagery to convey the complex nature of divine or demonic forces.

4,300-Year-Old Egyptian Tomb with Stunning Paintings of Donkeys

In March 2024, archaeologists in Egypt announced they discovered a 4,300-year-old tomb with remarkable wall paintings of donkeys threshing grain on a floor. The tomb is located at Dahshur, a site with royal pyramids and a vast necropolis that's about 33 kilometers (20 miles) south of Cairo. The paintings were found in a mastaba, a rectangular mud-brick tomb with a flat roof and sloping sides. There were also other scenes of life in ancient Egypt, such as ships sailing the Nile river, and goods being sold at a market, the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science published March 24, 2024]

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: Hieroglyphic inscriptions found on the tomb's walls say the burial belongs to a man named Seneb-Neb-Af and his wife Idet. The inscriptions state that Idet was a priestess of Hathor — a sky goddess associated with sensuality, maternity and music — while Seneb-Neb-Af held several positions in the royal palace that involved dealing with the administration of tenants.

It's hard to know exactly what duties Seneb-Neb-Af had, Stephan Seidlmayer, an archaeologist with the German Archaeological Institute who is leading excavations at the site, told Live Science. A nearby town was controlled by the palace, and he may have decided who got to live there and been in charge of administering funds for the community, Seidlmayer said.

The date of the site was determined based on the style and content of the inscriptions, the design of the mastaba and the style of the pottery, Seidlmayer said. He noted that the couple probably lived in the late fifth dynasty or early sixth dynasty, around 4,300 years ago. At this time, pyramids were still being constructed in Egypt, but they were smaller than those that had been built in the fourth dynasty at places like Giza.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024