Home | Category: Art and Architecture

PERSPECTIVE AND UNNATURAL POSES IN ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ART

"Walk In The Garden" on limestone, New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, c 1335 BC:; A relief of a royal couple in the Armana style, thought to be Akhenaten and Nefertiti

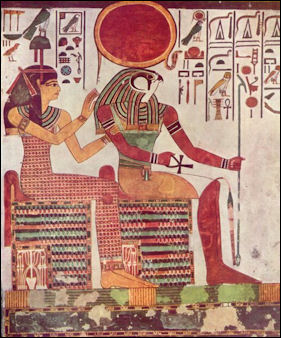

The Egyptians never developed perspective. Human heads often looked like the heads of flounders and soles — profiles with two frontal eyes placed on them. The human body was also twisted in an awkward position in which the shoulder faced the viewer but the waist and legs faced sideways. Quantity — such as number of prisoners killed in a battle or animals killed on a hunting trip — was expressed with the items painted in long rows. Ordinary people and servants were generally depicted as considerably smaller than gods, pharaohs, and other important people.

Different points of view often appeared in the same picture. An image of fisherman might include a side view of the fishermen and a top view of the fish swimming in a pond. It was considered important to show all the important features of a person which some say is why individuals are drawn with combined front and side views. The head is usually a side profile with the eyes drawn as they appear from the front. The shoulders and skirts are also presented from a front view.

Reliefs and paintings were often shown in profile with the eyes, eyebrows, shoulder and upper torso present on one head. While unnatural, these perspectives have become conventions of Egyptian art. Dorthea Arnold, curator of Egyptian art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, told Smithsonian, "These artistic conventions set the way to show people: axial, not symmetrical, afrontal confrontation, a set number of poses. It was almost like a language. Yet it was elastic, capable of any number of variations within the formula. It showed how creative the artist could be within the canon."

RELATED ARTICLES:

PAINTING IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TOMB PAINTINGS africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Art of Ancient Egypt: Revised Edition” by Gay Robins (2008) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Painting and Relief” by Gay Robins (2008) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Wall Paintings” by Francesco Tiradritti and Sandro Vannini (2008) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Art” Multilingual Edition by Salima Ikram (2018) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Art” by Rose-Marie Hagen, Rainer Hagen, Norbert Wolf (2018) Amazon.com;

“Reading Egyptian Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Egyptian Painting and Sculpture”

by Richard H. Wilkinson (1994) Amazon.com;

“Principles of Egyptian Art” by H. Schafer and John Baines (1986) Amazon.com;

“Atlas of Egyptian Art” by Émile Prisse d'Avennes (1991) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Statues: Their Many Lives and Deaths” by Simon Connor (2022) Amazon.com;

“Highlights of the Egyptian Museum” by Zahi Hawass (2011) Amazon.com;

“Hidden Treasures of Ancient Egypt: Unearthing the Masterpieces of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo” by Zahi Hawass (National Geographic, 2004) Amazon.com;

“The Royal Women of Amarna: Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt" (1996) Amazon.com;

“Eternal Egypt: Masterworks of Ancient Art from the British Museum”

by Edna R. Russmann (2001) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt At The Louvre” by Guillemette & Marie-Helene Rutschowscaya & Christiane Ziegler (trans Lisa Davidson). Andreu (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Egypt and the Ancient Near East”

by New York The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Peter F Dorman, et al. (1988) Amazon.com;

Human and Animal Figures in Ancient Egyptian Art

In the endeavor to show every part of the body, if possible in profile, as being the most characteristic point of view, the Egyptian artist designed a body, the incongruities of which wore quite contrary to nature. As a whole we may consider it to be in profile, for this is the usual position of the head, the arms, the legs, and the feet. In the profile of the head, however, the eye is represented en face, whilst the body comes out in the most confused fashion. The shoulders are given in front view, whilst the wrist is in profile, and the chest and lower part of the body share both positions. With the chest, for instance, the further side is en face, the nearer in profile, the lower part of the body must be considered to be three-quarter view, as we see b} the position of the umbilicus. The hands are usually represented in full and from the back, hence we find that in cases where the hands are drawn open or bent, the thumb is almost always in an impossible position. The feet are always represented in profile, and probably in order to avoid the difficulty of drawing the toes, they are always drawn both showing the inner side, though in finished pictures, when the calves of the legs are drawn, the inner and outer sides are rightly distinguished from each other. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

In addition to these peculiarities, the Egyptians usually observed two general laws, both of which had a great influence on the drawing of the human figure. One arm or foot was in advance of the other, it must always be the further one from the spectator; a figure therefore which looked towards the right could only have the left arm or foot in advance, and vice versa. The reason of this law is self-evident; if the right arm were extended, it would cut across the body in an ugly and confusing manner.

It is more difficult to find an explanation for the other law, by which all figures in their rightful position were supposed to look to the right, thus turning the right side to the spectator. This position was a fundamental rule with the Egyptian artist,' and whenever he was at liberty to represent the figure as he pleased, he always made it turn to the right; when for any reason he was obliged to draw it looking toward the left, he contented himself with simply reversing his design, regardless of the contradictions to which such a course gave rise. The statues of the Old Kingdom show us that the pleated part of the gala skirt was always on the right side, and in all the drawings in which the figure is turned to the right it is also represented thus. From the statues we see further that the long scepter was always held in the left hand, and the short one in the right; this is also correctly shown in all figures that are drawn looking towards the right. On the contrary, in the figures which are only mechanical inversions of those turned to the right, the sceptres as well as the sides of the skirt always change places.

The same rules were observed in the drawing of animals, which were represented in profile with the exception usually of a few parts of the body, like the eyes and sometimes the horns, which would be more characteristic drawn en face. Animals also always advance that foot or arm which is the further from the spectator; birds even are not excepted from this rule.

Why Does Ancient Egyptian Painting Look Flat

Nefertari tomb painting Why did the ancient Egyptians depict people, animals and objects on a flat, two-dimensional plane? Martin McGuigan wrote in Live Science: Drawing any object in three dimensions requires a specific viewpoint to create the illusion of perspective on a flat surface. Drawing an object in two dimensions (height and breadth) requires the artist to depict just one surface of that object. And highlighting just one surface, it turns out, has its advantages. "In pictorial representation, the outline carries the most information," John Baines, professor emeritus of Egyptology at the University of Oxford in the U. K. told Live Science. "It's easier to understand something if it is defined by an outline. " [Source: Martin McGuigan, Live Science, July 10, 2022]

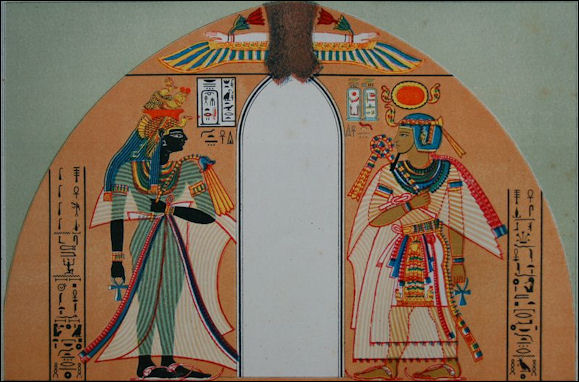

When drawing on a flat surface, the outline becomes the most important feature, even though many Egyptian drawings and paintings include details from several sides of the object. "There is also a great focus on clarity and comprehensibility," Baines said. In many artistic traditions, "size equals importance," according to Baines. In wall art, royalty and tomb owners are often depicted much larger than the objects surrounding them. If an artist were to use a three-dimensional perspective to render human proportions in a realistic scene with a foreground and background, it would go against this principle.

The other reason for depicting many objects on a flat, two-dimensional plane is that it aids the creation of a visual narrative. "One only has to think of [a] comic strip as a parallel," Baines said. There are widely accepted principles that organize how ancient Egyptian visual art was created and interpreted. "In origin, writing was in vertical columns and pictures were horizontal," Baines said. The hieroglyphic captions "give you information that is not so easily put in a picture. " More often, these scenes don't represent actual events "but a generalized and idealized representation of life. "

Egyptian visual art used "more or less universal human approaches to representation on a flat surface," Baines said. Egyptian art influenced art in the ancient Near East," such as ancient Syrian (or Levantine) and Mesopotamian art, Baines said. The same conventions can be seen in many other ancient traditions of art. Maya art also uses pictorial scenes and hieroglyphic script. Although classical Greek and Roman art is an exception, there are even examples of similar artistic conventions for two-dimensional drawing and painting from medieval Europe. As Baines explained, "It's a system that works very well and so there's no need to change it. "

Realism and Deviations from Traditional Styles in Ancient Egyptian Art

Ancient Egyptian did not consider their traditional style as the only possible way of drawing; for even during the Old Kingdom they emancipated themselves to a certain extent from this traditional style. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

In a tomb of the 4th dynasty, for instance, we meet with individual figures which are treated in a perfectly natural manner — they turn their backs to us, or advance the wrong leg and commit similar crimes allowed indeed by nature but not by Egyptian art. These figures are also drawn with such certainty of touch that we cannot regard them as mere experiments or isolated attempts; the artists who sketched them were evidently accustomed to work in this free style. In this ancient period therefore, there must have been, besides the strict old-fashioned style, a younger freer school of art, though the latter was evidently not regarded with so much respect as the former. Whoever liked might have his house decorated in this style, but it was not considered suitable for the tomb of a man of rank. Here it was only right that the formal traditional style should have undivided sway, and if an artist sometimes allowed himself a little liberty, it was at most with one of the unimportant figures. In fact, whenever we meet with one of these unconventional figures in a tomb, it is generally in the case of a fisher or a butcher, or perhaps of an animal such as a gazelle.

During the Old Kingdom we meet with a realistic school, which was never of much account, side by side with the official conventional art, and in later times also we find the same conditions everywhere — they are as it were the sign manual of the whole history of Egyptian art. The pictures of the Old Kingdom have one conspicuous merit — the clearness of the drawing. This result is evidently obtained by the artist placing his figures close together in horizontal lines. Even the most complicated scenes, the confusion of the hunt, a crowded herd, are rendered distinct and comprehensible, thanks to this division into lines one above the other. The ancient artist was always conscious of the extent of his power. He moreover preferred to walk in the old ways, and to follow the same lines as his predecessors.

Amenhotep I

Three-Dimensional Painting in Ancient Egypt

Not all pictorial representation in ancient Egypt was purely two-dimensional. Some scholars say that a painting of Nefertari in her tomb in the Valley of the Queens features the first example of three-dimensional painting, with facing using the technique of Chiaroscuro. The first full frontal representation of a Pharaoh was discovered by Spanish archaeologists in 2004. The 3,500-year-old portrait was found sketched on a plaster-coated board in a Luxor tomb and thought to depict Tutmosis III.

According to Baines, "Most pictorial art was placed in an architectural setting. " Some compositions on the walls of tombs included relief modeling, also known as bas relief, in which a mostly flat sculpture is carved into a wall or mounted onto a wall. In the tomb of Akhethotep, a royal official who lived during the Fifth Dynasty around 2400 B.C., we can see two scribes (shown below) whose bodies are sculpted into the flat surface of the wall. As Baines explained, the "relief also models the body surface so you can't say that it's a flat outline" because "they have texturing and surface detail in addition to their outlines. " [Source: Martin McGuigan, Live Science, July 10, 2022]

In many examples dating as far back as 2700 B.C. in the Early Dynastic Period, artists painted on top of a relief to add even more detail, as seen in the image of the two scribes in a relief from Mastaba of Akhethotep at Saqqara, Old Kingdom from around the 5th Dynasty, ca 2494-2345 B.C. It shows two scribes facing each other. One is writing on a tablet, whilst the other is holding up some parchment. Above them are several hieroglyphs and below there are two images of flying birds.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024