QUARRYING IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Building a pyramid

Elizabeth Bloxam of University College London wrote: “Research into the technologies used to extract and transport stone from quarries is still an underdeveloped field of study in Egyptology, despite the large-scale use of these materials in antiquity. Ancient quarry sites are the “forgotten” archaeological sites, even though they can comprise material culture such as roads, settlements, epigraphic data, and often spectacular partly finished monumental objects. Moreover, ancient production sites can enhance our understanding of the lives of the non-elite in antiquity, in particular the social organizations of raw material procurement, an aspect that still remains poorly understood. [Source:Elizabeth Bloxam, University College London, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Ancient quarrying sites often present extensive cultural landscapes comprising a range of material culture; however, their research potential is still not fully recognized. Current research is re- shaping ideas about these poorly understood activities, for instance, the major use of stone tools and fire in extracting hard stones, transmission of stone-working technologies across often deep time depths, and the role of skilled kin-groups as a social construct rather than large unskilled labor forces. Although questions of chronology of extraction techniques, methods, and development of theoretical approaches to interpretation are still in their early stages, with a continued emphasis on archaeological and geological survey of these sites, the potential exists to further address some of these important questions.”

See Separate Article: ORNAMENTAL AND BUILDING STONE IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ; MINING IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Hatnub: Quarrying Travertine in Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw (2011) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Technology and Innovation” by Ian Shaw (2012)

Amazon.com;

”The Production, Use and Importance of Flint Tools in the Archaic Period and the Old Kingdom in Egypt” by Michał Kobusiewicz (2016) Amazon.com;

“Stone Tools in the Ancient Near East and Egypt: Ground Stone Tools, Rock-cut Installations and Stone Vessels from Prehistory to Late Antiquity” by Andrea Squitieri and David Eitam (2019) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Construction and Architecture” by Somers Clarke and R. Engelbach (2014) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Masonry: The Building Craft” by Somers Clarke and R. Engelbach | (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Pyramids” by Mark Lehner (1997) Amazon.com;

“How the Great Pyramid Was Built” by Craig B. Smith (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Builders of the Pyramids” by Zahi Hawass (2009) Amazon.com;

Materials That Were Quarried in Ancient Egypt

Elizabeth Bloxam of University College London wrote: “Stone. Rocks quarried and crafted in antiquity are usually placed into two broad categories as either “hard” stones or “soft” stones. “Hard” stones are usually igneous rocks such as basalt, granite, diorite, granodiorite, dolerite, and porphyritic rocks, but can also include metamorphic rocks such as gneisses, metagabbro, serpentinite, and sedimentary rocks such as silicified sandstone (often termed “quartzite”) and chert. Key hard stone sources exploited during the Pharaonic period are the deposits of granite and granodiorite in Aswan, silicified sandstone at Gebel el-Ahmar near Cairo and on the west bank at Aswan, basalt in the Northern Fayum at Widan el-Faras, and “Chephren gneiss” from Gebel el-Asr (“Chephren’s Quarry”) in Lower Nubia. The greatest range of other hard stone deposits are located in the Eastern Desert. [Source: Elizabeth Bloxam, University College London, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

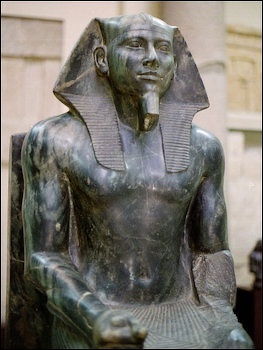

diorite statue of Khafre

““Soft” stones usually refer to sedimentary rocks such as sandstone, limestone, gypsum, and travertine. All these rocks occur in a range of geographical locations throughout Egypt, with limestone, sandstone, and travertine deposits largely situated inside the Nile valley between Cairo in the north and Esna in the south. Key soft stone deposits exploited during antiquity occur at Hatnub (travertine), in the region of the Muqattam hills near Cairo (limestone), and between Aswan and Edfu at Gebel el-Silsila. The exception to these Nile valley locations are sources of gypsum that occur most densely in the Northern Fayum.

“In general terms during the Pharaonic period, the greatest use of hard stones occurred between the Predynastic (late 4th millennium B.C.) into the mid Old Kingdom (mid 3rd millennium B.C.). Stone vessels, life-sized statuary, and elements in monumental architecture were key uses of the largest range of hard stones, peaking between the 4th and 5th Dynasties. Aswan red granite and basalt were the most extensively exploited hard stones utilized in architectural elements of the Old Kingdom pyramid complexes at Giza and Abusir. The utilitarian use of largely hard stones for tools, grinding equipment, and other domestic purposes was constant throughout antiquity. Soft stones such as sandstone and limestone were used almost continuously in the construction of monumental buildings from the Early Dynastic into the Roman Period. Travertine was also an important soft stone exploited in antiquity, particularly for stone vessels and also monumental architecture.

See Separate Article: ORNAMENTAL STONE IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Soft Stone and Hard Quarrying in Ancient Egypt

Greg Dawson of Minnesota State University, Mankato wrote: “Limestone was quarried one of two ways it was either obtained from the surface rock, or else they tunneled and found the rock they needed. It is known that they possessed excellent copper tools such as saws and chisels which were capable of cutting any kind of limestone. Chisels and wedges were the tools of choice, the chisels were used for cutting the rock away from the sides, and the wedges were then used to detach the base for the block. In tunnel quarrying a shaft was cut between the roof and the rock to be detached, this was done to allow a man to get behind the rock by chipping at it vertically. On two sides two other men made splits down the two sides so that they could remove it from where it was. Wedges were then inserted into the holes that were made and driven down in to achieve a split in the rock, wet wooden wedges were also used in this procedure because they would swell up when the got wet and would crack the rock that way. This put them in a very tight spot to work. [Source: Greg Dawson, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“In surface quarrying the same exact method was used except that they had more of an advantage because it gave them more room to move around, but the rock that they got from open mine quarrying was not as fine a grade of limestone as the kind that they could find buried in the earth. +\

“Quarrying of the harder stones such as granite was a more labor intensive task, they had to use a hard greenish stone called dolerite, and pounded around the base of the stone to try to detach it from its base. In order to get to the higher quality rock they would light fires on the granite to get it to a certain temperature. Cold water would then be thrown on it to cool it fast this would cause the outer layers to crack and fall off leaving the harder rock from the inside for them to use. +\

Quarrying Technology and Tools in Ancient Egypt

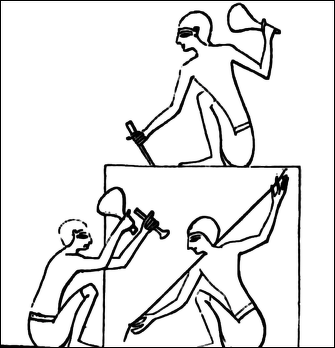

Stone working tools

James Harrell of the University of Toledo wrote: “Throughout the Dynastic Period until near the end of the Late Period, building stones were quarried with copper (and later bronze) chisels and picks. The chisels were hammered with wooden mallets and the metal pick heads were hafted on wooden handles. It is probable that chert (or flint) pick heads were also used, as these are harder, although more brittle, than the metal tools, but so far there is little archaeological evidence for this. Implements of copper and the harder bronze were tough enough to work the softer stones, but were quickly blunted and abraded. They were entirely unsuited for the harder crystalline, dolomitic, and silicified limestones and well- cemented sandstones, and for such materials

Building stones were typically extracted from the quarries as rectangular blocks. Vertical trenches were first cut along the back and two lateral sides of an intended block, and then the block’s open front face was undercut to complete the separation from bedrock. In a final step, using the same tools, the now loose block was often dressed (trimmed) to adjust its size and shape. This basic approach to quarrying remained unchanged from the Old Kingdom down to Roman times. During the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, however, hammered iron wedges set in lines of pre-cut wedge-shaped holes were sometimes used to split limestone and sandstone, especially the harder varieties. The extracted stone blocks were transported from the quarries and to the construction sites on sledges during the Dynastic Period and on wagons thereafter. Transport by boat was also common when the construction sites were distant from the quarries.

“There were two quarrying innovations introduced early in the New Kingdom. The first of these, dating to the Amarna Period, was the extraction of limestone and sandstone blocks with standardized dimensions that were small enough for one workman to carry. These are the so-called talatat blocks, which measure about 52 centimeters (one cubit) by 26 centimeters (a half-cubit) by 26 cm. Unique to these blocks was a new method for detaching them from the bedrock. A series of closely spaced, roughly cylindrical, horizontal holes were cut underneath the block from front to back. The partitions between these holes would have been progressively cut away, leaving some in place for support, until the block was free. A second advance, first appearing during the reign of Amenhotep III, was in the limestone and, at Gebel el-Silsila, sandstone galleries, where annotated lines were painted on ceilings to mark the quarrying progress. Numerous quarries have these markings, but the best example is at el- Dibabiya. Quarrying of talatat blocks ceased by the end of the 18th Dynasty, but the marking of gallery ceilings continued into the Late Period.”

Analysis of Ancient Egyptian Stone Extraction Technologies

Elizabeth Bloxam of University College London wrote: “Most of the hard and soft stone sources known in Egypt were exploited to varying degrees and purposes since prehistory into at least the Roman Period. The nature of the deposit, in terms of its physical properties, was a key factor in how the rocks were extracted. Although later quarrying is always destroying evidence of the earliest extraction techniques, it is generally agreed that the earliest hard stone quarrying in the Predynastic for ornamental objects, such as stone vessels, utilized more easily accessible boulders or “blocky” remains of hard stones. It was not until the quest for hard stones used in monumental architecture and life-size statuary that it became necessary to target bedrock. [Source: Elizabeth Bloxam, University College London, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

wooden butterfly braces used in working stone

“There is still considerable debate about the technologies of both hard and soft stone extraction, in particular the extent to which metal tools were used. Given the constant re-use of metal, there is an obvious bias in the archaeological record, because such material in the form of tools is rarely found in production sites. Stone tools are without exception the most common implements found in production sites. Yet in accordance with Arnold and also from subsequent studies, there is generally an undervaluing of the role that stone tools did actually play in both the extraction and dressing of stone blocks, even after the introduction of metal technologies . Moreover, in the hard stone granite and silicified sandstone quarries in Aswan and the gneiss quarries at Gebel el-Asr (“Chephren’s Quarry”), fresh evidence suggests that stone tools in combination with fire were key technologies used in ornamental stone production from the Old Kingdom into at least the Ptolemaic Period. Similarly, the use of fire-setting to extract graywacke in the Wadi Hammamat has recently been discovered by the author. Charcoal, burnt flakes of stone, and often fired mud-bricks are key remains left by this process in primary extraction and also in secondary production for channeling, trimming, and shaping blocks. Pounding with stone tools to further flatten and smooth surfaces is also attested by the clearly visible marks left by these tools on partially worked objects found in the quarries.

“Although it is extremely difficult to determine when fire-setting was gradually phased out as a technology in hard stone quarrying, the current view is that with the introduction of iron technology by the Ptolemaic Period, the “wedging” technique took precedence. Typified by the distinctive “trapezoidal” wedge holes left on quarry faces, these have been subject to intense scrutiny, in terms of technology as well as establishing chronologies of quarrying. Metal tools such as picks and chisels seem to have been employed in some part of the process of cutting the wedge holes, given the distinctive marks left by these tools on quarry faces; yet controversy still remains as to whether wood or metal wedges were employed to finally split the stone.

carving and shaping building stones

“The use of metal in the extraction of soft stones is also problematic; the suggestion from studies of the Gebel el-Silsila sandstone quarries is that “softer copper chisels” were utilized during the Old and Middle Kingdoms, with “harder bronze chisels” coming into use by the New Kingdom. The blocks were then believed to have been levered out using wooden beams. Fresh arguments have suggested that the use of pointed picks and axes has been largely overlooked, and similar to hard stone quarrying, stone tools may have had a greater use in the dressing and quarrying of soft stones with metal chisels employed only for special purposes. In addition, recent research undertaken at the Wadi el-Nakhla limestone gallery quarries near Deir el-Bersha, particularly those of the Late Period, has revealed grids of red ocher lines on the roof that presumably had some practical purpose in designating work areas for the quarriers.

“It is important to remember that similar to hard stone quarrying, geological awareness was key in determining the best method of extraction. With this aspect in mind, it has to be noted that in the well-preserved Old Kingdom gypsum quarries at Umm el-Sawan, the combination of locally acquired fossilized wood, minimally worked into rod-shaped pieces, found associated with stone hammers largely of chert occurs in significant quantities to suggest their wholesale use as tools.

“Finishing of objects in the quarries seems to be dependent upon how far the stone had to travel to the Nile. At the Aswan granite quarries, which lie directly on the Nile, objects seem to have been almost completed in the quarries. The famous “unfinished obelisk” and New Kingdom Osiride statue, which still lie attached to the bedrock, are such examples. In quarries outside of the Nile valley, evidence from discarded objects suggests that they were only partially completed to form rough outlines of their intended final form, probably to reduce the transport weight.”

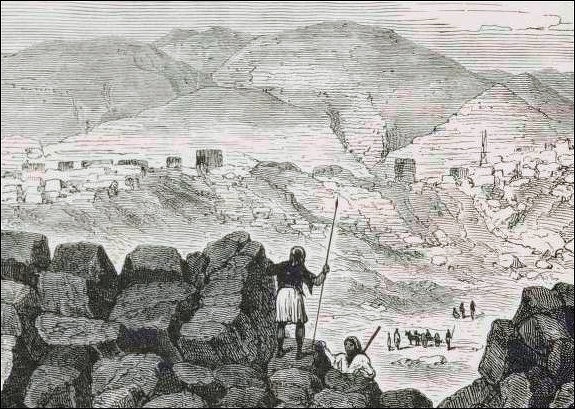

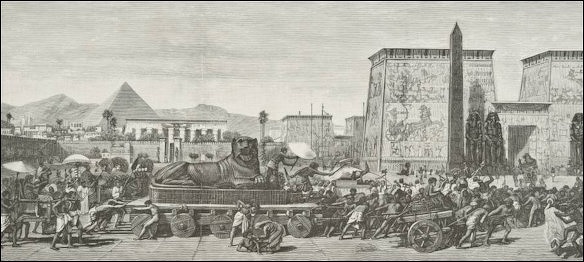

Quarries of Tourah (1878)

transporting stone blocks

Logistics of Stone Transport in Ancient Egypt

Elizabeth Bloxam of University College London wrote: “Transport infrastructure in quarries can vary according to the nature of the ground surface—and steep descents—over which the stone had to travel on its journey to the Nile. The importance of water in the transport process of large objects was clearly vital, the termini of most quarry roads linking in some way to the Nile or its nearest tributaries. New Kingdom quarry roads associated with the transport of large ornamental objects from the silicified sandstone quarries at Gebel Gulab on the west bank at Aswan are some of the most extensive and best preserved in Egypt . These networks comprise secondary paved roads that lead directly into New Kingdom quarries from where large objects were extracted. The roads all converge onto a central artery, which traverses Gebel Gulab and then changes character into more ramp-like structures to ease passage of the stone down towards the Nile. [Source: Elizabeth Bloxam, University College London, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The world’s oldest paved quarry road connects the Old Kingdom basalt quarries of Widan el-Faras with the shores of ancient Lake Moeris at Qasr el-Sagha in the Northern Fayum. Constructed from local sandstone, limestone, basalt, and fossilized wood, the terminus of the 11 kilometers road at a quay utilized the waters of Lake Moeris during high Nile floods. Although determining the levels of the Nile flood during the Old Kingdom still remains controversial, there is indirect evidence to make a correlation between high Nile floods and the transport of basalt on a large scale to the pyramids on the Giza plateau at this time.

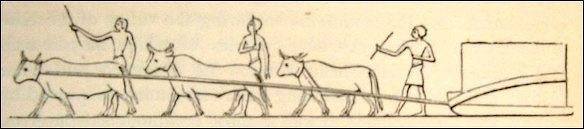

“Due to the lack of archaeological evidence in relation to vehicles associated with the movement of stone, there still remains the archaeological problem as to what type of vehicle was used in the overland transportation of stone. In general, there has been a tendency to rely on the iconographic record to explain these practices, these suggesting the use of low-lying sledges. The Middle Kingdom Djehutihotep transport scene as well as a New Kingdom (18th Dynasty) depiction found in the Tura limestone quarries of a sledge conveying a block of stone drawn by oxen are often referred to. To what extent rollers were used under the sledges is still a matter of debate, although the use of unfixed rollers with sledges to move heavy weights over large distances has been proven impractical.

“Of the quarry roads described above, there are no wear marks, fixed tracks, or other indicators as to how the stone was moved over them. However, rare vehicle tracks associated with several loading ramps at Gebel el-Asr (“Chephren’s Quarry,” Old Kingdom) have certainly suggested that other types of conveyance, other than low-lying sledges, were used to transport stone from this quarry to the Nile. In essence, it seems as if adaptation to local geomorphological conditions was key, and ways to minimize overland transportation were clearly sought. Recent research in the Aswan granite quarries has indicated that the construction of canals into the “unfinished obelisk quarry” was clearly to avoid any overland movement of these objects.

a vision of Israeli slaves in Egypt produced in 1878

Social Context of Quarrying in Ancient Egypt

Elizabeth Bloxam of University College London wrote: “Assessing the social context of quarry and mining expeditions in the Pharaonic period in terms of numbers involved and hierarchies has been difficult to determine, given that associated settlement evidence is scant. Even in quarries outside of the Nile valley, such as Gebel el-Asr (“Chephren’s Quarry”), Widan el-Faras, and Umm el-Sawan, only small ephemeral camps characterized by low-level dry-stone walls and the use of natural rock overhangs have provided any evidence of habitation. Ceramics are also minimal in these and other quarry sites; hence, estimating the numbers of people involved in these activities is problematic and why there has been a reliance on textual sources. However, even taking into account poor preservation, recent findings cannot attest to quarry labor forces being over a maximum of 200 individuals, thus largely contradicting the Wadi Hammamat quarry inscriptions, which list expeditions into the tens of thousands. [Source: Elizabeth Bloxam, University College London, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“In terms of provisioning of the labor force in quarries remote from permanent settlements and crucial access to water, evidence from excavation of two small camps and several wells at Gebel el-Asr (“Chephren’s Quarry”) in the Western Desert has given us some decisive insights. Constituting dwellings for no more than 25 people, one-third of each camp was devoted to food production, in particular bread making. In addition to consumption of local fish, birds, and mammals, access to water was relatively easy from shallow wells only up to one meter in depth. The shallowness of the wells has provided important insights into the climatic conditions that prevailed during the Old Kingdom exploitation, indicating seasonally wetter periods far removed from what we see today.

“Grappling with the archaeological problems of fragmentary data, particularly in terms of understanding the social organization of resource exploitation in the Pharaonic era, it has been important to reassess our ideas about the make up of quarry and mining labor forces from concepts in other areas of the social sciences. In particular cross-cultural comparison, anthropology, social archaeology, and landscape archaeology have provided useful models through which production data can be reinterpreted. Developing such methodologies is important if we are to understand the social context behind these activities, away from largely unreliable explanations via just a few written sources. Recent research is now widening the gap between the textual version of practice vis-à-vis the archaeological record.

“It has recently been argued that small groups of specialists, rather than large detachments of unskilled workers, made up quarrying and mining labor forces. These groups, loosely structured around kinship ties, might explain the general observation of undeniably skilled practice and transmission of specific extraction technologies over many generations.”

Building Stones in Ancient Egypt

unfinished stones for Menkaure's pyramid

James Harrell of the University of Toledo wrote: “The building stones of ancient Egypt are those relatively soft, plentiful rocks used to construct most temples, pyramids, and mastaba tombs. They were also employed for the interior passages, burialchambers, and outer casings of mud-brick pyramids and mastabas. Similarly, building stones were used in other mud-brick structures of ancient Egypt wherever extra strength was needed, such as bases for wood pillars, and lintels, thresholds, and jambs for doors. Limestone and sandstone were the principal building stones employed by the Egyptians, while anhydrite and gypsum were also used along the Red Sea coast. A total of 128 ancient quarries for building stones are known (89 for limestone, 36 for sandstone, and three for gypsum), but there are probably many others still undiscovered or destroyed by modern quarrying. [Source: James Harrell, University of Toledo, OH, Environmental Sciences, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“The building stones of ancient Egypt are those relatively soft, plentiful rocks used to construct most Dynastic temples, pyramids, and mastaba tombs. For the pyramids and mastabas made largely of sun-dried mud- brick, building stones were still employed for the interior passages, burial chambers, and outer casings. Similarly, building stones were used in other mud-brick structures of ancient Egypt (e.g., royal palaces, fortresses, storehouses, workshops, and common dwellings) wherever extra strength was needed, such as bases for wood pillars, and lintels, thresholds, and jambs for doors, but also occasionally for columns. Ptolemaic and Roman cities along the Mediterranean coast, Alexandria chief among them, followed the building norms of the rest of the Greco- Roman world, and so used stone not only for temples but also for palaces, villas, civic buildings, and other structures. Limestone and sandstone were the principal building stones used by the Egyptians. These are sedimentary rocks, the limestone consisting largely of calcite (CaCO3) and the sandstone composed of sand grains of mostly quartz (SiO2) but also feldspar and other minerals. The Egyptian names for limestone were jnr HD nfr n ajn and jnr HD nfr n r-Aw, both translating as “fine white stone of Tura-Masara” (ajn and r-Aw referring, respectively, to the cave-like quarry openings and the nearby geothermal springs at Helwan). Sandstone was called jnr HD nfr n rwDt, or occasionally jnr HD mnx n rwDt, both meaning “fine, or excellent, light-colored hard stone.” Although usually translated as “white,” here HD probably has a more general meaning of “light colored.” Sandstone is not normally considered a hard rock (rwDt), but it is often harder than limestone. In the above names, the nfr (fine) or HD or even both were sometimes omitted, and in the term for sandstone the n was later dropped.

“From Early Dynastic times onward, limestone was the construction material of choice for temples, pyramids, and mastabas wherever limestone bedrock occurred—that is, along the Mediterranean coast and in the Nile Valley from Cairo in the north to Esna in the south. Where sandstone bedrock was present in the Nile Valley, from Esna south into Sudan, this was the only building stone employed, but sandstone was also commonly imported into the southern portion of the limestone region from the Middle Kingdom onward. The first large-scale use of sandstone occurred in the Edfu region where it was employed for interior pavement and wall veneer in Early Dynastic tombs at Hierakonpolis and for a small 3rd Dynasty pyramid at Naga el- Goneima, about 5 kilometers southwest of the Edfu temple. Apart from this pyramid, the earliest use of sandstone in monumental architecture was for some Middle Kingdom temples in the Theban region (e.g., the Mentuhotep I mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri and the Senusret I shrine at Karnak). From the beginning of the New Kingdom onward, with the notable exception of Queen Hatshepsut’s limestone mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri, most Theban temples were built either largely or entirely of sandstone. Further into the limestone region, sandstone was also used for the Ptolemaic and Roman Hathor temple at Dendara, portions of the Sety I and Ramesses II temples at Abydos, and the 18th Dynasty Aten temple at el-Amarna. The preference for sandstone over limestone as a building material coincided with the transfer of religious and political authority from Memphis in Lower Egypt to Thebes in the 18th Dynasty. The Egyptians also recognized at this time that sandstone was superior to limestone in terms of the strength and size of blocks obtainable, and this permitted the construction of larger temples with longer architraves.

“The Serabit el-Khadim temple in the Sinai is of sandstone, and temples in the Western Desert oases were built of either limestone (Fayum and Siwa) or sandstone (Bahriya, Fayum, Kharga, and Dakhla), depending on the local bedrock. In the Eastern Desert, limestone was used for the facing on the Old Kingdom flood-control dam in Wadi Garawi near Helwan (the “Sadd el-Kafara”; Fahlbusch 2004), and sandstone was the building material for numerous Ptolemaic and Roman road stations. Both types of bedrock in the Nile Valley and western oases hosted rock-cut shrines and especially tombs, and these are the sources of many of the relief scenes now in museum and private collections. Limestone and sandstone were additionally employed for statuary and other non-architectural applications when harder and more attractive ornamental stones were either unaffordable or unavailable. In such cases, the otherwise drab- looking building stones were usually painted in bright colors. Conversely, structures built of limestone and sandstone often included some ornamental stones, most notably granite and granodiorite from Aswan, as well as silicified sandstone, but also basalt and travertine in the Old Kingdom.”

Building Stone Quarries in Ancient Egypt

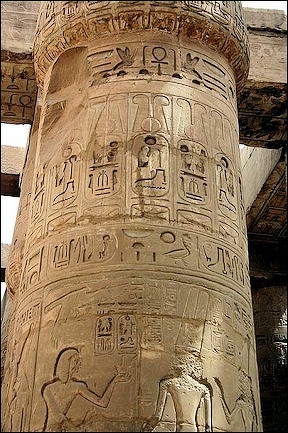

stones in the great columns of the Hypostyle Hall in Karnak Temple

There are 128 known building-stone quarries of ancient Egypt, including 89 for limestone, 36 for sandstone, and three for gypsum, one of the latter also supplying anhydrite. Most of the quarries are still either largely or entirely intact. James Harrell of the University of Toledo wrote: “From descriptions of the quarry and the stone found there “it can be seen that the character of limestone or sandstone from a given quarry will vary according to the formation supplying it. Because of their great value in cement production, far more geological information has been published on the limestone formations than on those of sandstone or gypsum, and this difference is reflected in the level of detail in the formation descriptions. The geologic ages of sedimentary rock layers (and consequently also formations) decrease from south to north in the Nile Valley due to their northerly inclination, and this means that quarry-stone characteristics also change in a downriver direction. With rare exception, it is not yet possible to identify by analytical means the specific quarry supplying a given building- stone sample, but the formation and, hence, general location in the Nile Valley can usually be established by petrographic microscopy. Although the list of known ancient quarries is long, it is still far from complete. There are undoubtedly many more quarries awaiting discovery, as well as others that are forever lost because they have been destroyed through urban growth, modern quarrying, or natural erosion and weathering. Modern quarrying of limestone for the cement industry and sandstone for rough construction blocks is responsible for most of the destruction. Although not destroyed, numerous sandstone quarries are no longer accessible because they are now under Lake Nasser. [Source: James Harrell, University of Toledo, OH, Environmental Sciences, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“The building stones used at ancient construction sites usually came from nearby quarries. This has been convincingly demonstrated by Klemm and Klemm for the Memphite necropolis, although few actual limestone quarries are known for this region (others are probably buried under wind-blown sand or obscured by weathering of exposed outcrops). A good example of one of the known quarries is beside the 4th Dynasty Khafra pyramid at Giza. Notable exceptions to the local derivation of building stones are the high-quality limestones from Tura and Masara and sandstone from Gebel el-Silsila. These quarries, which are among the largest in Egypt, provided large, fracture-free blocks of uniform color and texture, and these were employed at sites distant from the quarries. The Tura and Masara limestones, for example, were used extensively for the exterior casing on Old and Middle Kingdom pyramids and mastabas in the Memphite necropolis as well as for the linings of interior passages and burial chambers within these structures. It has been claimed that this limestone was carried as far as Upper Egypt for other construction applications but this is unconfirmed. The Gebel el-Silsila sandstone was the principal building material for temples the quarry. When there was no good source of local building stone, rock was usually brought from quarries upriver because it was easier to float a heavily loaded boat down the Nile than to sail it upriver against the current, even with a good northerly wind.

“Limestone from the ancient quarries was typically light gray on unweathered surfaces, but was also sometimes nearly white or pale yellowish to pinkish. The rock is relatively soft due to its abundant calcite and generally high porosity. The so-called “indurated” (i.e., more consolidated than normal) limestone owes its greater hardness to either more coarsely crystalline calcite (in crystalline limestone), or the presence of secondary dolomite (CaMg[CO3]2; in dolomitic limestone) or secondary quartz (SiO2; in silicified or cherty limestone). Non- carbonate components are often present in the limestones, especially quartz silt/sand and clay minerals, and these were deposited in the original lime sediment. The extensively recrystallized limestones, which megascopically resemble metamorphic marble, are considered ornamental stones as are some of the colored limestone varieties— dark gray to black bituminous limestone, buff limestone, and red-and-white limestone breccia.

“The quarried sandstone was usually light to medium brown in color with occasional yellowish, reddish, or purplish shadings. The hardness of the rock depends on the amount and type of cementing agent holding the sand grains together. The most common cements in Egyptian sandstones are quartz, iron oxides, calcite, and clay minerals (also referred to as “clay matrix”). The iron oxide is mainly yellowish to brownish goethite or limonite (nFeO[OH] or FeOOHnH2O, respectively) but also sometimes reddish hematite (Fe2O3). The clay is whitish in color and usually either illite (of variable composition but similar to muscovite mica, KAl2[AlSi3O10][OH]2), kaolinite (Al2Si2O5[OH]4), montmorillonite ([Na,Ca]0.3[Al, Mg]2Si4O10[OH]2nH2O), or a mixture of these. When these cements are sparse, the rock is friable (i.e., easily crumbled), and when abundant and filling all the intergranular pore spaces, the rock is well- indurated. The sandstones with abundant quartz cement are the hardest of all and are referred to as silicified sandstone, one of the main ornamental and utilitarian stones. Both limestone and sandstone (and other rock types as well) darken on weathered surfaces and where long exposed to the elements will develop a patina known as “desert varnish.” This has a variable composition but normally consists of iron and manganese oxides plus clay minerals. It thickens and darkens with age, eventually becoming nearly black, especially on sandstone.”

Quarrying Building Material in Ancient Egypt

Quarries in the Giza area

James Harrell of the University of Toledo wrote: “The quarrying of building stones in ancient Egypt was usually done in “opencut” (or “open-cast”) workings on the sides of hills and cliffs, but in some cases the workers followed desirable rock layers underground and in the process created cave- like “gallery” quarries. Unquarried rock pillars were left to support the roofs in the larger galleries but cave-ins have subsequently occurred at some of these sites. Galleries are relatively common for limestone and such excavations locally penetrate over 100 meters into hillsides. [Source: James Harrell, University of Toledo, OH, Environmental Sciences, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“A gallery that is part of the 18th Dynasty limestone quarry on Gebel Sheikh Said, now largely destroyed, is unique for the 1.6 by 0.5 meters temple plan painted on one of its bedrock pillars. Presumably the stone for the temple was to come from this quarry, but the plan does not correspond to any of the known limestone temples in Egypt. Many of the limestone galleries later became the sites of Coptic Christian hermitages and monasteries, with some of the latter still active today, such as, for example, at Deir el-Amir Tadros, Deir Abu Mina, Deir el-Aldra Maryam, and Deir el- Ganadla, all near Assiut. With the exception of the Gebel el-Silsila quarry, galleries were never cut in sandstone.

“The choice of quarry location would have been based on several factors, including the quality of the stone (appearance, soundness, and attainable block size), and proximity to the construction site or Nile River if water transport was needed. That quality was more important than ease of accessibility is evidenced by the many workings on hillsides and cliffs that are high above the more easily reached rock outcrops at lower elevations.

“Gypsum deposits in the form of veins within limestone and other sedimentary rocks are common throughout Egypt, and many of these occurrences were probably exploited during the Dynastic Period for gypsum plaster. Nowhere are these veins thicker or more numerous than in the Fayum’s Umm el- Sawan and Qasr el-Sagha quarries, the former being the source of gypsum used for Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom vessels, and both also supplying the raw material for ancient Egypt’s gypsum plaster. The anhydrite and gypsum along the Red Sea coast, in contrast, occur in bedded sedimentary formations and these would have been the source of gypsum plaster and building stones in the Ptolemaic and Roman settlements of this region. While there were probably many workings for these rocks, only one quarry is known. This is near Wadi el-Anba’ut and was primarily a source of ashlar blocks (both anhydrite and gypsum) for the nearby Roman port at Marsa Nakari.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Bir Umm Fawakhir images, Carol Meyer, Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago.

Hammamat Quarries

Wadi Hammamat is a dry river bed in Egypt's Eastern Desert, about halfway between Al-Qusayr and Qena. It was a major mining region and trade route east from the Nile Valley in ancient times. Quarrying expeditions to the Eastern Desert are recorded from the second millennia B.C. The site is described in the earliest-known ancient geological map, the Turin Papyrus Map. Rocks found here include basalts, schists, bekhen-stone (an especially prized green metagraywacke sandstone used for bowls, palettes, statues, and sarcophagi) and gold-containing quartz.The Narmer Palette, from 3100 B.C., is one of a number of early and predynastic artifacts that were carved from the distinctive stone of the Wadi Hammamat. Pharaoh Seti I is recorded as having the first well dug to provide water in the wadi, and Senusret I sent mining expeditions there. [Source Wikipedia]

It stands to reason that the powerful monarchs of the 12th dynasty, who were such great builders, did not neglect the Hammamat quarries. Under the first of these kings, for instance, 'Entef, the lord high treasurer, succeeded, after searching for eight days, in finding a species of stone, “the like of which had not been found since the time of the god. " No one, not even the hunters of the desert, had known of this quarry. Under Amenemhat III. also, no fewer than 20 men of the mountains, 30 stone masons, 30 rowers (?), and 2000 soldiers were employed for the transport of the monuments from Hammamat. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

During the period subsequent to this account the inscriptions almost cease or contain no particulars. '' Yet we must not therefore conclude that from this time the quarries were little worked; numberless proofs of the contrary are to be found in the buildings of the 13th dynasty, as well as in those of the New Kingdom. It was again the business-like everyday character that the work assumed, that led to the cessation of the inscriptions. Hammamat, at this epoch, when nothing in the way of building was considered too difficult, was placed almost in the same rank as Tura and Gebel Silsila. Though we hear no more of the want of water or of the difficulty of communication, yet a new danger seems now to have arisen. From the above-mentioned satirical writing — • certainly an untrustworthy source of information — we hear of a military expedition ''' being sent to Hammamat “in order to destroy those rebels "; exclusive of officers, the number of troops employed is given as 5000, the text therefore cannot refer to one of the petty wars frequently carried on with the wretched Bedouins of these mountains. If in other respects we may believe the account, there must have been' a mutiny amongst the workmen to necessitate the employment of so great a number of soldiers.

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024