Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex) / Culture, Science, Animals and Nature

PETS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Pet cheetah in Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptians kept pets. Pet cats date back to ancient Egypt. Dogs go back thousands of years before that. The Egyptian may have succeeded in domesticating cranes, ibex, gazelles, oryx and baboons. Bas reliefs show men trying to tame hyenas by tying them up and force feeding them meat.

Robert Partridge of the BBC wrote: “Animals of all kinds were important to the Ancient Egyptians, and featured in the daily secular and religious lives of farmers, craftsmen, priests and rulers. Animals were reared mainly for food, whilst others were kept as pets. The bodies of sacred animals and some pets were often mummified and given elaborate burials. The bodies of some rams were mummified and equipped with gilded masks and even jewellery. Great cats were hunted, and their skins were greatly prized, but they were not always killed and the smaller cats, such as the cheetah, were often tamed and kept as pets. A gilded figure of a cheetah, with the distinctive 'tear' mark, was found on one of Tutankhamun's funerary beds. “ [Source: Robert Partridge, BBC, February 17, 2011]

In a 2021 study published in World Archeology, Polish scientists announced the discovery of a 2000-year-old pet cemetery on the coast of the Red Sea, near the ancient port of Berenice, in southwest Egypt and said it provided evidence that people in the ancient world kept animals as pets not only for utilitarian purposes. “The fundamental conclusion is a noticeable desire of human beings to be in the company of animals, resulting not only from their functional or economic benefits," the study reads. [Source: Daily Paws, March 20, 2021]

Archaeologists examined the site from 2011–2020. They discovered 585 bodies clearly identified as animals, but there were plenty of additional remains the scientists couldn't identify, indicating many more animals were buried there. No human remains, though, were found. More than 91 percent of the identifiable animals are domestic cats, scientists said. Just over 5 percent are dogs while 2. 7 percent are monkeys. Archaeologists also found one Barbary falcon, one Rüppell's fox, and two macaques, which are another kind of primate. The project's lead researcher Marta Osypińska, a zooarchaeologist at the Polish Academy of Sciences, told Live Science that there were no signs that the animals had been killed by people — which has been evident at other sites. In fact, the animals were all "carefully buried," some wrapped in blankets or next to shells or other mementos.

“The study was also able to determine the ages of some of the animals, along with their sexes and whether they suffered from specific diseases — which, evidently, their humans cared for. The scientists could even tell that some of the animals had eaten fish. The study added that the smaller dogs and macaques have no real service value. It seemed evident that these animals were likely just human companions when they were alive. “We think that in Berenice the animals were not sacrifices to the gods, but just pets," Osypińska told Live Science.

See Separate Articles:

WILD ANIMALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SACRED ANIMALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: CULTS AND WORSHIP africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ANIMAL MUMMIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

BABOONS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Cat In Ancient Egypt” by Jaromir-Malek Amazon.com;

“Cats in Ancient Egypt: A Captivating Guide” (2025) Amazon.com;

“Beloved Beasts”by Salima Ikram (2006) Amazon.com;

“Divine Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2015) Amazon.com;

“Soulful Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt” by Edward Bleiberg, Yekaterina Barbash , et al. (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptians and the Natural World: Flora, Fauna, and Science” by Prof. Dr. Salima Ikram, Jessica Kaiser, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt's Wildlife: An AUC Press Nature Foldout”

by Dominique Navarro and Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Egypt's Wildlife: Past and Present” by Dominique Navarro (2016)

Amazon.com;

“A Guide to Extinct Animals of Ancient Egypt” by Anthony Romilio (2021) Amazon.com;

“Between Heaven and Earth: Birds in Ancient Egypt” by Rozenn Bailleul-LeSuer (2012) Amazon.com;

“Egypt - Ancient and Modern: History, Birds and Wildlife” (Birding Travelogues)

by Mark Dennis and Sandra Dennis (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt” by Richard H. Wilkinson (2003) Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Wild Animals as Pets in Ancient Egypt

The Egyptians were fond of cheetahs and kept herds of gazelles and antelopes. Oryxes and other kinds of antelope were kept as household pets. Even though the Egyptians may have tamed elephants there is no evidence they were domesticated like elephants in ancient Carthage. Elephants in elaborate tombs were found in cemetery in Hierakonpolis, dated to 3500 B.C. One of the elephants was ten to eleven years old. That is the age when young males are expelled from the herd. Modern animals trainers say elephants at that age are young and inexperienced and can be captured and trained.

Wealthy Egyptians at all times kept menageries, in which they brought up the animals taken by the lasso or by the dogs in the desert, as well as those brought into Egypt by way of commerce or as tribute. From the neighbouring deserts they obtained the lion and the leopard (which were brought to their masters in great cages), the hyena, gazelle, ibex, hare, and porcupine, were also found there; from the incense countries and from the upper Nile came the pard, the baboon, and the giraffe; and from Syria the bear and the elephant. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

They felt still greater delight when these animals were tamed, when the Ethiopian animal the kderi was taught to dance,'' and to understand words; or when the lion was trained to conquer his savage nature and to follow his master like a dog. Ramses II. possessed a tame lion which accompanied him to battle,° and which lay down in the camp at night before the tent of the royal master. Pet apes are found at all periods; these were imported from foreign parts. " Xebemchut, an Egyptian courtier in the reign of King Khafre, possessed two uncouth long-maned baboons, and, accompanied by them, he with his wife inspected the work of his artisans, and certainly the great lord mightily enjoyed the inspection of his people which the apes undertook for their part. ' ]\Iost people however contented themselves with one small monkey, which we sometimes see sitting under a chair busy pulling an onion to pieces, or turning out the contents of a basket; and though as a rule the monkey was

Possibly the imaginative huntsman hoped also to obtain as a prize one of those marvellous animals spoken of by everybody, but which no living man had ever seen the griffon, the swiftest of all animals, which was half-bird, half-lion; or the sphinx, that royal beast with the head of a man or of a ram, and the body of a lion; or the winged gazelle, or even the sag, the creature uniting the body of a lioness with the head of a hawk, and whose tail ended in a lotus flower. All these animals and many others of similar character were supposed to exist in the great desert, and Khnumhotep, the oft-mentioned governor of Middle Egypt under the 12th dynasty, caused a panther with a winged face growing out of his back to be represented amongst the animals in his great hunting scene. He was probably of the opinion that such a creature would cause the neighbourhood of Beni Hasan to be unsafe.

Cats in Ancient Egypt

cat mummies Domesticated cats were present in ancient Egypt at least as early as 2000 B.C. So strong was the Egyptian love of cats that laws were established protect them from injury and death. Cats were mummified, buried in bronze coffins, and honored with elaborate funerals and a period of mourning.

Cats are believed to have been domesticated around 3000 B.C. to get rid of grain-eating rodents. The first domesticated cats are believed to have been African wild cats, small pale yellow creatures with black feet. It's not clear when domesticated cats first arrived, but archaeologists have found cat and kitten burials dating as far back as 3800 B.C., Live Science reported.

Robert Partridge of the BBC wrote: Cats were kept to protect food stores from rats, mice and snakes, and were kept as pets. They are shown in paintings beneath their owners' chairs, or on their laps. Egyptian cats resembled modern tabby cats. The Egyptian name for cat is 'miw'. Cats also had a symbolic or religious meaning, as represented by the goddess Bastet, and in later periods of Egyptian history cat mummies were used as offerings to the gods.” [Source: Robert Partridge, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Egypt's most well known cat is the sphinx. The Great Sphinx of Giza is 73-meter (240-foot) -long monument that has the face of a man and the body of a lion. It is perhaps the most famous example of a monument with feline features, although historians aren’t exactly sure why the Egyptians went to the trouble of carving the sphinx.

Cats were "mummified in the millions" and buried as offerings. Priests carefully watched over temples cats. Their movements were sources of omens. In the 19th century so many mummified cats were exhumed that they were shipped to Britain as ballast, then ground into fertilizer."

Lions were said to accompany the pharaohs in battle and were give names like “Slayer of his Foes.” Killing a lion was regarded as an act of extraordinary bravery. Inscriptions describe the breeding and burial of lions. Thus far only one lion mummy has been found. Sakhmet (also spelled Sekhmet), was depicted as having the head of a lion on the body of a woman. She was known as a protective deity, particularly during moments of transition, including dawn and dusk. [Source: Benjamin Plackett, Live Science, April 17, 2021]

Fondness for Cats in Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptians are famed for their fondness of cats. Cats were associated with Bastet, the goddess of fun, pleasure and protection and the bringer of good health. The belief that cats have nine lived is believed to have originated in Egypt based on the fact that cats can survive long falls. There were temples for Bastet, where mummified cats were left as offerings and kittens were bred by the thousands to meet the demand for offerings.

The ancient Egyptians produced lovely sculptures of cats. Cats were so adored that the ancient Egyptians named or nicknamed their children after them. These included the name "Mitt"' (which means cat) for girls, according to University College London. Herodotus wrote that cats were considered so important that exporting them was illegal and killing one was a crime punishable by death. Owners of cats that died naturally were required to shave off their eyebrows as a mark of respect when mourning the loss.

Benjamin Plackett wrote in Live Science: There's no shortage of cat-themed artifacts — from larger-than-life statues to intricate jewelry — that have survived the millennia since the pharaohs ruled the Nile. The ancient Egyptians mummified countless cats, and even created the world's first known pet cemetery, a nearly 2,000-year-old burial ground that largely holds cats wearing remarkable iron and beaded collars. [Source: Benjamin Plackett, Live Science, April 17, 2021]

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The Pyramid texts of ancient Egypt describe a royal guard dog that was anointed with perfumed ointment, wrapped in linen, ceremonially buried in a coffin paid for out of the royal purse, and laid to rest in a custom-built tomb.When the Achaemenid king Cambyses II conquered Pelusium in Egypt in 525 B.C. he apparently placed dog, cats, sheep and other sacred animals in his ranks so that the Egyptians would stop fighting. It worked so well that he conquered the city. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, January 16, 2022]

Ancient Egyptian artwork featuring cats includes a faience (glazed ceramic) ring of a cat with its kittens, dating to Egypt's Ramesside- Third Intermediate period (1295–664 B.C.) and a bronze and gold cat dating to Egypt's Late Period, Dynasty 26 or later (664-30 B.C.). The head of lioness-headed deity Sekhmet dates to Egypt's New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, reign of Amenhotep III, 1391-1353 B.C. An amulet with Sekhmet datesto Egypt's Third Intermediate period (1070–664 B.C.).

A cosmetic vessel in the shape of a cat dates to Egypt's Old Kingdom (1990–1900 B.C.). A cat amulet crafted from faience dates to Egypt's Third Intermediate period or later (1070–664 B.C.). Cuff bracelets decorated with cats, dating to Egypt's New Kingdom (1479–1425 B.C.). A painting of a cat sitting under a chair was found in the Tomb of Ipuy (New Kingdom/Ramesside (1295–1213 B.C.). A cat, likely a representation of the goddess Bastet, atop of a box for an animal mummy. It dates to the Late Period–Ptolemaic Period (664–30 B.C.).

Why were cats so deeply loved valued in ancient Egypt? Much of this reverence is because the ancient Egyptians thought their gods and rulers had cat-like qualities, according to a 2018 exhibition on the importance of cats in ancient Egypt held at the Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art in Washington, D. C. Specifically, cats were seen as possessing a duality of desirable temperaments — on the one hand they can be protective, loyal and nurturing, but on the other they can be pugnacious, independent and fierce. Cats were likely also loved for their abilities to hunt mice and snakes. Benjamin Plackett wrote in Live Science: To the ancient Egyptians, this made cats seem like special creatures worthy of attention, and that might explain why they built feline-esque statues. [Source: Benjamin Plackett, Live Science, April 17, 2021]

Herodotus on Cats in Ancient Egypt

Fifth Century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: Of the animals that live with men there are great numbers, and would be many more but for the accidents which befall the cats. For when the females have produced young they are no longer in the habit of going to the males, and these seeking to be united with them are not able. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A.D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

To this end then they contrive as follows — they either take away by force or remove secretly the young from the females and kill them (but after killing they do not eat them), and the females being deprived of their young and desiring more, therefore come to the males, for it is a creature that is fond of its young. Moreover when a fire occurs, the cats seem to be divinely possessed; for while the Egyptians stand at intervals and look after the cats, not taking any care to extinguish the fire, the cats slipping through or leaping over the men, jump into the fire; and when this happens, great mourning comes upon the Egyptians.

And in whatever houses a cat has died by a natural death, all those who dwell in this house shave their eyebrows only, but those in which a dog has died shave their whole body and also their head. The cats when they are dead are carried away to sacred buildings in the city of Bubastis, where after being embalmed they are buried; but the dogs they bury each people in their own city in sacred tombs

Cat Mummy Industry in Ancient Egypt

Benjamin Plackett wrote in Live Science: There's evidence of a more sinister side to the ancient Egyptians' feline fascination. There were likely entire industries devoted to the breeding of millions of kittens to be killed and mummified so that people could be buried alongside them, largely between about 700 B.C. and A. D. 300. In a study published in 2020 in the journal Scientific Reports, scientists carried out X-ray micro-CT scanning on mummified animals — one of which was a cat. This enabled them to take a detailed look at its skeletal structure and the materials used in the mummification process. [Source: Benjamin Plackett, Live Science, April 17, 2021]

When the researchers got the results back, they realized the creature was a lot smaller than they had anticipated. "It was a very young cat, but we just hadn't realized that before doing the scanning because so much of the mummy, about 50 percent of it, is made up of the wrapping," said study author Richard Johnston, a professor of materials research at Swansea University in the United Kingdom. "When we saw it up on the screen, we realized it was young when it died," less than 5 months old when its neck was deliberately broken.

"It was a bit of a shock," Johnston told Live Science. That said, the practice of sacrificing cats wasn't rare. "They were often reared for that purpose," Johnston said. "It was fairly industrial, you had farms dedicated to selling cats. " That's because many of the creatures were offered as a votive sacrifice to the gods of ancient Egypt, Mary-Ann Pouls Wegner, an associate professor of Egyptian archaeology at the University of Toronto previously told Live Science. It was a means to appease or seek help from deities in addition to spoken prayers. It's not exactly clear why it was considered desirable to buy cats to be buried with.

Dogs in Ancient Egypt

Robert Partridge of the BBC wrote: “'Man's best friend' was considered not just as a family pet, but was also used for hunting, or for guard duty, from the earliest periods of Egyptian history. Pet dogs were well looked after, given names such as 'Blackey' or 'Brave One', and often provided with elaborate leather collars. The mummy of a dog, probably a royal pet; was found in a royal tomb in the Valley of the Kings. [Source: Robert Partridge, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Jarrett A. Lobell and Eric Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine, “The ancient Egyptians also cherished their dogs, not only as deities ("The Dog Catacomb"), but also as companions in this life — and the next. A mummy of a small dog that dates to the fourth century B.C. was found in the sacred Egyptian city of Abydos in 1902 alongside that of a man identified on his coffin as Hapi-Men. Both mummies are now in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Hapi-Men and his companion, "Hapi-Puppy," were recently part of a project to reexamine several mummies from the museum's collection. Hapi-Puppy was taken to the University of Pennsylvania Hospital for a CT scan that confirmed he was indeed a dog (not a cat, as was also thought possible.) [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell and Eric Powell, Archaeology magazine, September/October 2010]

According to anthropologist Janet Monge, who led the scan study, Hapi-Puppy died at about two years of age, more like an adolescent than a baby, and had the same size, stockiness, and power of a Jack Russell terrier. "Hapi-Men must have loved his dog, and after his death, it seems that the dog pined away and died soon enough to have been mummified and buried with his master," says Salima Ikram of the American University in Cairo. According to Ikram, this practice was not uncommon. "There are much earlier Middle Kingdom (2080-1640 B.C.) tombs that depict a man and his dog, and both are named so that they can survive into the afterworld together," she says.

Hunting Dogs in Ancient Egypt

Pharaoh houndsPacks of dogs were usually employed in desert hunting; they were allowed to worry and to kill the game. The hunting dog was the great greyhound with pointed upright ears and curly tail; this dog is still in use for the same purpose on the steppes of the Sudan. It is a favorite subject in Egyptian pictures to show how cleverly they would bury their pointed teeth in the neck or in the back paws of the antelopes. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

These graceful dogs also ventured to attack the larger beasts of prey. A picture of the time of the Old Kingdom represents a huntsman who, having led an ox to a hilly point in the desert, lies in wait himself in the background with two greyhounds. The ox, finding himself abandoned, bellows in terror; this entices a great lion to the spot, and the huntsman watches in breathless suspense, ready in a moment to slip the leash from the dogs and let them fall on the lion, while the king of animals springs on the head of the terrified ox.

Under the Old Kingdom, besides the T'esem, we meet with a small earless dog, which was also used for coursing; it may be that in former times they also tamed the prairie dogs. Under the 11th dynasty there were certainly three different breeds of dog known in Egypt, and later there appear to have been even more. It is interesting that the names given by Egyptian huntsmen to their dogs were often foreign ones. Of the four dogs represented on the stela of the ancient King 'Entef, the first two are called Behka'e and Pehtes, which, as the accompanying inscription informs us, mean “gazelle “and “black "; it is not quite clear what the fourth name Teqeru signifies, the third is 'Abaqero, in which Maspero has recognised with great probability the word Abaikour, the term by which the Berberic nomads of the Sahara still call their greyhounds. "

Greyhounds in Ancient Egypt

Greyhounds are regarded as the world's oldest breed of dog along with the dingo, New Guinea singing dog, and African basenji. They were pictured in mural from a settlement in Turkey dating to 4000 B.C. By some reckonings the oldest dog breed, the saluki, is thought to have emerged in 329 B.C.

Greyhounds were raised and bred by Egyptians and were pictured in ancient Egyptian tomb paintings. The oldest reference to a greyhound is a carving of the Tomb of Amten in the Nile Valley, dated between 2900 and 2751 B.C. It shows three images greyhound or greyhound-type dogs. Two are attacking deer and one is attacking an animal that looks like a wild goat.

Extremely fast and maneuverable, greyhounds were used for hunting animals such as gazelles and wolves and coursing hares. Over the centuries they have been used to pursue all kinds of animals including deer and foxes. Their natural prey is hares.

Greyhounds were linked with royalty, who treated their dogs so well that ordinary people resented them because they were treated better than people. The dogs of some pharaohs had 2,000 attendants.

Probably no wealthy household was complete without the splendid great greyhounds," still employed in the Sudan. They were most precious to the huntsman, for they were swifter than the gazelle and had no fear even of a lion. The Egyptian who was no sportsman however also loved to have these beautiful creatures about him; they accompanied him when he went out in his sedan chair, and lay under his chair when he was in the house. If we may believe the representations of a Memphite tomb, Ptahhotep, a high official under the 5th dynasty, insisted upon keeping his three greyhounds with him, even while he was listening to the harps and flutes of his musicians, in spite of the howls with which these dogs of the Old Kingdom seem to have accompanied the music. These greyhounds, the T'esem, do not appear to have been natives of Egypt; under the New Kingdom at any rate they seem to have been brought from the incense countries of the Red Sea. Nevertheless this breed of dog was always popular in Egypt, and a tale of the time of the 20th dynasty relates how a prince preferred to die rather than part from his faithful greyhound. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Dog Catacombs in Ancient Egypt

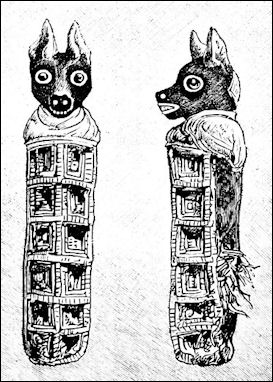

dog mummies Paul Nicholson wrote in Archaeology magazine, “ In 1897, French Egyptologist Jacques De Morgan published a map of the necropolis of Saqqara, the burial place of Egypt's first capital city, Memphis. The map includes the only known plan of the "Dog Catacombs" at the site, but no information about the date or circumstances of their discovery. In fact, virtually nothing is known of these catacombs. [Source: Paul Nicholson, Archaeology magazine, September/October 2010. Nicholson is Director, Cardiff University-Egypt Exploration Society Mission to the Dog Catacombs]

Last year, I began a Cardiff University-Egypt Exploration Society mission to the catacombs, which date from the Late and Ptolemiac Periods (747-30 B.C.), the last dynasties before the Romans conquered Egypt. We hope to learn if the De Morgan plan is accurate and see if we can find any clues to the early history of the catacombs' exploration. Right now we are completely remapping the catacombs and looking for clues to the circumstances of their discovery, such as travelers' graffiti and lamps from earlier explorers.

The first catacomb, one of two main locations for dog burials at Saqqara, was the subterranean element of the Temple of Anubis — the jackal-headed god of the dead — a little to the south. According to the map, the temple had a long corridor that was probably a ceremonial route and numerous shorter tunnels on each side filled with thousands of mummified dogs and animal remains. The majority of these animals would have been votive offerings by pilgrims who hoped that the deceased animals would intercede with the deity on their behalf. Others, however, may have been representatives of the god and lived within the temple compound. Some of the dogs that were buried in special niches in the tunnel walls, rather than being piled in the great mass of remains, may be those animals. Many seem to have lived to considerable age, while other animals met their deaths after only a few months.

But the question remains — are they really all dogs, as the catacombs' name suggests? Preliminary examination by the American University in Cairo's Salima Ikram, the project's animal bone specialist, suggests that many of the mummified animals, now mostly lacking their wrappings, are indeed dogs. But according to Ikram, "Anubis was a kind of super-canid, so it is likely that jackals, foxes, and maybe even hyenas were mummified and given as offerings to Anubis." There is also still debate about exactly what kind of canid Anubis was meant to represent. Although the concept of dog breeds is a modern one, we hope to discover more information about the species, types, ages, and genders of the animals in the catacombs to understand how the god was perceived.

Ancient Egyptian Child Buried with 142 Dogs

According to Heritage Daily, Russian archaeologists affiliated with the Center for Egyptological Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences uncovered the remains of an 8-year-old child and 142 dogs in a late antique Egyptian necropolis at Deir el-Banat, 100 kilometers (62 miles) to the west of Cairo, when they came across the unusual human-canine burial. Galina Belova, who examined the canine remains, concluded that all the dogs died at the same time. Given that there was no sign of violence, Belova suggests that perhaps the dogs may have drowned.[Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, January 29, 2023]

Candida Moss wrote in Daily Beast: Though dog burials are well known in ancient Egypt, it is unclear why the child was buried alongside (or, better, atop) the canine remains. To add to the strangeness, the child’s head was covered by a “linen bag” something that is unusual even though there is a precedent for it. Heritage Daily reports that the burial is something of a “mystery. ”

Naqada culture dog from around 3500 BC

Unusual archaeological discoveries make for splashy news items, so it’s worth thinking through the options in greater detail. The Daily Beast spoke to archaeologist and ancient historian Dr. Mark Letteney, a postdoctoral fellow at MIT, about how archaeologists approach strange artifacts and what we might make of this burial. In the case of this burial of dogs, the broader data set includes Greco-Roman and late antiquity Egyptian burials. When something unusual is found, said Letteney, he usually turns to those who specialize in that thing. In this case Letteney looked to specialists in burial (Dr. Liana Brent, a mortuary archaeologist) and canine burials in particular (Dr. Victoria around Moses, a zooarchaeologist who specializes in dog sacrifice and burial).

As it turns out, dog internment is in evidence almost everywhere you find human burials in the ancient Mediterranean world. “In Italy,” said Letteney, “we have good evidence for, and studies of, dog sacrifice, and particularly puppies” by scholars like Victoria Moses, Jacopo De Grossi Mazzorin, Claudia Minniti, and Barbara Wilkens. Inhabitants of Rome purportedly crucified dogs for their failure to warn them about a stealth attack by the Gauls in the fourth century B.C. (they were awakened by geese instead).

Though this is not at all clear from news reports, the discovery itself was made in November 2007 and, thus, the Belova and Savinetsky findings have received some scholarly attention. In her article “Man’s Best Friend for Eternity: Dog and Human Burials in Ancient Egypt,” Dr. Salima Ikram, a Distinguished Professor of Egyptology at the American University in Cairo, discusses the phenomenon of dog burials in ancient Egypt and tackles this find in particular. Ikram notes that while the dogs had been “crudely mummified” the child itself was preserved through natural desiccation. Ikram notes that the burial is highly unusual and does not fit with standard practice in which dogs served a kind of amuletic purpose. It is possible, she notes, “that the child had been a caretaker of dogs raised to be votive offerings” and that, when it died, the child was honored by being placed alongside its charges. Ikram notes that a similar burial, in which a human was buried on top of thousands of dogs, was unearthed in a gallery at the Temple of Anubis (Anubeion) at Saqqara. If this reading is correct then the co-burial of the child and the dogs would be mutually beneficial: “the dogs would be guaranteed care [in the afterlife], and the child would be assured an eternal existence, the goal of every Egyptian. ”

With respect to this particular find, said Letteney, we should exercise caution about some of the reported details of the excavation. The confident statement that the child was 8 years old at the time of their death is difficult to confirm. Letteney explained that while it is easy enough to identify a child (because the bones are small and there’s no evidence that the subject had gone through puberty) it’s difficult to be precise. “There is no way to say, ‘this child was 8 years old’ based on bones alone,” said Letteney, “It is impossible. You can give a range, and the best archaeologists can often say with older children is ‘pre-pubescent,’ which generally is indicated as ‘under 14 or so.’” (This is why, in her work, Ikram describes the child as “under 14 years of age. ”) Gender is even more challenging: only a tombstone or gender specific grave goods allow us to tentatively deduce the sex of a deceased child.

Did the Ancient Egyptians Worship Animals

cat killing the demon Apep

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “Some of the most interesting and misunderstood information about the Ancient Egyptians concerns their calendarical and astrological system. Of the greatest fallacy about Ancient Egypt and it's belief in astrology concerns the supposed worship of animals. The Egyptians did not worship animals, rather the Egyptians according to an animals astrological significance, behaved in certain ritualistic ways toward certain animals on certain days. For example, as is evidenced by the papyrus Cairo Calendar, during the season of Emergence, it was the advisement of the Seers (within the priestly caste), and the omens of certain animals they saw, which devised whether a specific date would be favorable or unfavorable. +\ [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“The basis for deciding whether a date was favorable or unfavorable was based upon a belief in possession of good or evil spirits, and upon a mythological ascription to the gods. Simply, an animal was not ritually revered because it was an animal, but rather because it had the ability to become possessed, and therefore could cause harm or help to any individual near them. It was also conceived of that certain gods could on specific days take the form of specific animals. Hence on certain days, it was more likely for a specific type of animal to become possessed by a spirit or god than on other days. The rituals that the Egyptians partook of to keep away evil spirits from possessing an animal consisted of sacrifice to magic, however, it was the seers and the astrologers who guided many of the Egyptians and their daily routines. Hence, the origin of Egyptians worshipping animals, has more to do with the rituals to displace evil spirits, and their astrological system, more so than it does to actually worshipping animals.” +\

Animal Cults in Ancient Egypt

Two kinds of cult animal existed in ancient Egypt: 1) animals associated with a given deity that lived in a temple and were ceremonially interred; 2) creatures killed and mummified to act as votive offerings. The former existed in the earliest times, while the latter date from the Late Period (712–332 B.C.) and later. Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol wrote: “While there continues to be debate over precise definitions, it seems broadly agreed that cult animals in Egypt fall into two distinct groups. The first are specific specimens of a given species that were held to be an earthly incarnation of a particular deity, or at least in whom the deity could become incarnate. Resident in the god’s temple, they would be the subject of a suite of rituals, and would often receive elaborate treatment at death. These will be referred to as “Sacred Animals.” The other group are representatives of a species whose embalmed remains could be offered by pilgrims coming to seek the favor of a deity (“Votive Animals”). There would normally only be one example of the first kind at a time; deposits of the second kind could run into the hundreds or even thousands within a short period of time. Animals were also, of course, employed in temples as sacrificial victims. [Source: Aidan Dodson, University of Bristol, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Many of the gods and goddesses of ancient Egypt had animal forms. Obvious examples are the cat of Bastet, the ram of Khnum, the cow of Hathor, and the falcon of Horus, which reflected the deities’ iconic theriomorphic forms. However, Amun could also appear in the form of a goose, while a considerable number of deities had a bovine form. It is from the latter that our best evidence for the ritual that might surround a sacred animal comes. On the other hand, while it seems that bulls were allowed to live out their natural lives (although cf. below), other creatures were more ephemeral, for example a new falcon of Horus was installed each year at Edfu.

“A multiple burial-place...has been uncovered for the rams of Khnum on Elephantine, and remains deriving from such an installation have been found for the rams of Banebdjed at Mendes. It is likely that the baboons buried in niches in the walls of the catacombs at Tuna el-Gebel represent a succession of sacred animals of Thoth. However, the latter also contain very large numbers of embalmed ibises, which are clearly representatives of the other variety of cult-animal, the votive creature.

“Judging by the uniformity of their age at death and standardized treatment, it seems clear that votive animals were bred specifically for the purpose on an industrial scale, killed when they reached a given size, and then mummified for sale to pilgrims at a number of sacred places around Egypt. The range of treatments and elaboration of wrappings suggests the production of something for every pocket. It seems that they were deposited in a temple by pilgrims – perhaps with a prayer to the god whispered in its ear – and when the temple became cluttered, they were taken to an appropriate burial place. At Abydos, ibis mummies were buried within the confines of the 2nd Dynasty Shunet el-Zebib enclosure, but subterranean arrangements are found at Tuna, Western Thebes, Tell Basta, and various other locations. Most important of all, however, are the series of catacombs at Saqqara.

“As elsewhere, the catacombs of the Sacred Animal Necropolis at Saqqara seem to have been begun during the Late Period, and adjoin the aforementioned burial of the Mothers of Apis. They form part of a complex of temples and shrines located some 700 meters northeast of the Serapeum, together with major enclosures on the desert edge, and an as-yet little known set of chapels north and south of the Serapeum. Separate catacombs exist of ibises, baboons, falcons, and dogs, while cats were interred in extensions of New Kingdom tomb chapels on the edge of the Saqqara escarpment. In addition to literally millions of mummified animals and birds, a number of deposits of bronze divine figures were also made in the Sacred Animal Necropolis, clearly also votives brought by pilgrims.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024