Home | Category: Culture, Science, Animals and Nature

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN CULTURE

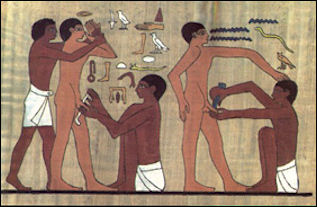

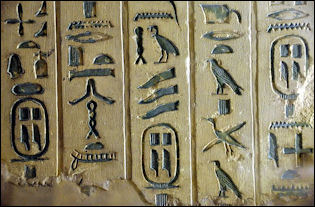

Circumcision from Sakkara The study of ancient Egyptian culture — whether it be art, music, dance, theater, literature or whatever — is based mostly on identifying scenes associated with each of these art forms from monuments, temples and tombs and translating and interpreting the inscriptions and texts found with them. Some information has been gleaned from artifacts found in burials.

One of the biggest problems with ancient Egyptian culture — particularly the art that is found in temples and tombs that have been excavated — is that it is so idealized and propagandized it is often difficult to derive meaningful information from it. This was a problem with a lot of ancient art. Artists tended to present the world as the commissioner of the art wanted it depicted rather than as it really was. Some of the most interesting Egyptians art is depicts scenes from everyday life such as people hunting and fishing and baking bread and purifying water.

In his book “The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” Toby Wilkinson deftly illuminates the pageantry and cultural sophistication of pharaohnic Egypt and highlights the fact that “the Egyptians were adept at recording things as they wished them to be seen, not as they actually were,” and that tomb decoration was “designed, above all, to reinforce the established social order,” for instance, showing a tomb’s owner dominating every scene, towering in size over his family and workers.” [Source: Michiko Kakutani, New York Times March 28, 2011]

Herodotus devoted nearly all of Book 2 of “Histories” to describing the achievements and the curiosities of the Egyptians. Over time the Greeks and Romans wiped out Egyptian culture. Later archaeologists and historians pieced together portraits of ancient Egypt’s kings, including Narmer, the first ruler of a united Egypt (whose reign began around 2950 B.C.) ; the warrior king Thutmose III, who secured Egypt’s control over the Transjordan; the eccentric Akhenaten who declared himself a co-regent with the sun; and Ramesses II, who ruled for an astonishing 67 years and would be immortalized in Shelley’s poem “Ozymandias.”

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Egyptian Culture” by Katherine Gleason (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw (1995) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptian Culture Revealed” by Moustafa Gadalla (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Burden of Egypt” by John A. Wilson (1951) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt and Early China: State, Society, and Culture” by Anthony J. Barbieri-Low and Marissa A. Stevens (2021) Amazon.com

“Visual and Written Culture in Ancient Egypt” by John Baines (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Culture Of Ancient Egypt” by John A. Wilson (1951) Amazon.com;

Ancient Egyptian Literature

pyramid text Egyptian literature doesn’t get much attention, especially compared to its art and architecture. Most of what has been written in the ancient Egyptian language consists of spells, incantations, lists, medical and scientific texts and descriptions of the netherworld. The ancient Egyptians produced fables, heroic tales, love poems and descriptions of battles but nothing that has stood the test of time like the Greek myths or Homer’s epics.

A representative passage from the “Pyramid Texts” goes: “The King is the Bull of the sky, Who conquers at will, Who lives on the being of every God, Who eats their entrails.”

The “ Ebers Papyrus” (1550 B.C.) is said to be the oldest book in existence. The Ani Papyrus (1200 B.C.) was 78 feet long. Texts like “The Story of Sinuhe,” “The Eloquent Peasant,” “The Report of Wenamun , “The Tale of Woe,” and The Teaching of Ankhsheshonq” are interesting stories in their own right but also offer invaluable insights into ancient Egyptian society and the daily life or ordinary Egyptians.

Literary texts were also free to concentrate on perceived moral injustices in everyday experience, rather than the abstract principles of cosmic order and disorder. Roland Enmarch wrote: Middle Egyptian poetry provides the most explicit examples, such as the “Tale of the Eloquent Peasant”, which explores issues of social justice that implicitly raise theodicean questions. Another Middle Egyptian poem, the “Teaching for Merikare”, culminates in a hymn to the creator god who asserts his care for suffering humanity (“When they weep, he is listening”), yet also portrays the creator as a stern father “slaying his son for the sake of his brother” . Suffering, even if it seems inexplicably harsh to humanity, thus serves a higher divine purpose, becoming the creator’s tool for chastising his errant creations’ behavior. [Source: Roland Enmarch, Liverpool University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship. org ]

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN LITERATURE africame.factsanddetails.com

Music in Ancient Egypt

Visitors to ancient Egypt often wrote about the abundance of music, dance, storytelling and songs in the kingdom and described feasts and ceremonies with musicians playing harps, lyres, tambourines, sistrums, “ mizmaar” (a reed flute), drums, lutes, cymbals and flutes. How Egyptian music sounded is not known.

Tomb paintings show musicians playing various instruments. One shows four women, thought to be professional entertainers, playing a harp, a lute, oboes and a lyre. The women appear to be dancing while they are playing. A small sculpture shows a musician kneeling as he plays a harp. Tomb paintings show the development of harps from something that resembled a hunter's bow to elaborate carved triangular instruments that resembled some kinds of modern harps.

Music was a key element in Egyptian religion. Some scholars believe it aimed to soothe the gods and encourage them to provide for their worshippers. Emily Teeter, an Egyptologist and research assistant at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago told Archaeology magazine: "For years people have debated what kind of music it was. But there's no musical notation left, and we're not sure how they tuned the instruments or whether they sang or chanted." Some scholars have suggested it may have sounded like rap because there was a string emphasis on percussion, and with this presumably rhythm. Images often show people stamping their feet and clapping. Examples of song lyrics are recorded on temple walls. Some of the songs were sung at at the Festival of Opet in Thebes when the cult images of the gods Amun, Mut, and Khonsu were brought by boat down the Nile and carried in a procession to renew the pharoah's divine essence. One lyric from the festival goes: “Hail Amun-Re, the primeval one of the two lands, foremost one of Karnak, in your glorious appearance amidst your [river] fleet, in your beautiful Festival of Opet, may you be pleased with it.” [Source: Julian Smith, Archaeology, Volume 65 Number 4, July/August 2012]

See Separate Article: MUSIC IN ANCIENT EGYPT factsanddetails.com

Dance in Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptians were a dance-loving people. Dancers were commonly depicted on murals, tomb paintings and temple engravings. Ideographs show a man dancing to represent joy and happiness. Pictorial representations and written records from as early as 3000 B.C. are offered as evidence that dance has a long history in the Nile kingdom. According to the “International Encyclopedia of Dance”, “dance was part of the Egyptian ethos and featured prominently in religious ritual and ceremony on social occasions and in Egyptian funerary practices regarding the afterlife.”The study of ancient Egyptian dance is based mostly on identifying dance scenes from monuments, temples and tombs and translating and interpreting the inscriptions and texts that accompanied them. [Source: “ International Encyclopedia of Dance”, editor Jeane Cohen]

According to the “International Encyclopedia of Dance”, dances were performed “for magical purposes, rites of passage, to induce states ecstacy or trance, mime; as homage; honor entertainment and even for erotic purposes.” Dances were performed both inside and outside; by individuals pair but mostly by groups at both sacred and secular occasions.

Dance rhythms were provided by hand clapping, finger snapping, tambourines, drums and body slapping. Musicians played flutes, harps, lyres and clarinets, Vocalizations included songs, cries, choruses and rhythmic noises. Dancers often wore bells on their fingers. They performed nude, and in loincloths, flowing transparent robes and skirts of various shapes and sizes. Dancers often wore a lot of make-up, jewelry and had strange hairdos with beads, balls or cone-shaped tufts, Accessories included boomerangs and gavel-headed sticks. “ Ab” , the hieroglyph for heart, was a dancing figure.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN DANCE factsanddetails.com

Ancient Egyptian Sports and Recreation

Egypt seemed to have no organized sports like Greece. Paintings depict wrestling matches as a battle of a superior over a weakling, not a match of equals. Men sometimes engaged in tug of wars and women played the vine game. Hieroglyphics from 4000 B.C. show the spread of boxing throughout the Nile. Tomb painting between 3400 and 1500 B.C. have images of running, swimming, rowing, and archery.

The Egyptians, Greeks and Romans played ball games. Hockey is one of the oldest stick and ball games. Early forms of hockey were played in ancient Egypt, Greece and Persia. Bowling evolve independently in Egypt, Polynesia and Germany. The ancient Egyptians played a game that was similar to modern bowling. Implements for a game similar to bowling were found in the tomb of a child buried around 5200 B.C.

Magic as a form of entertainment was known to the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans. A magical invocation from the New Kingdom funerary vase read: "You who come to disturb, I shall not let you disturb! You who come to strike, I shall not let you strike!"Book: “Magic in Ancient Egypt” by Geraldine Pinch, a professor of Egyptology at Cambridge University.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN SPORTS AND GAMES factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024