Home | Category: Culture, Science, Animals and Nature

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN LITERATURE

Egyptian literature doesn’t get much attention, especially compared to its art and architecture. Most of what has been written in the ancient Egyptian language consists of spells, incantations, lists, medical and scientific texts and descriptions of the netherworld. The ancient Egyptians produced fables, heroic tales, love poems and descriptions of battles but nothing that has stood the test of time like the Greek myths or Homer’s epics.

A representative passage from the “Pyramid Texts” goes: “The King is the Bull of the sky, Who conquers at will, Who lives on the being of every God, Who eats their entrails.”

The “ Ebers Papyrus” (1550 B.C.) is said to be the oldest book in existence. The Ani Papyrus (1200 B.C.) was 78 feet long. Texts like “The Story of Sinuhe,” “The Eloquent Peasant,” “The Report of Wenamun , “The Tale of Woe,” and The Teaching of Ankhsheshonq” are interesting stories in their own right but also offer invaluable insights into ancient Egyptian society and the daily life or ordinary Egyptians.

Literary texts were also free to concentrate on perceived moral injustices in everyday experience, rather than the abstract principles of cosmic order and disorder. Roland Enmarch wrote: Middle Egyptian poetry provides the most explicit examples, such as the “Tale of the Eloquent Peasant”, which explores issues of social justice that implicitly raise theodicean questions. Another Middle Egyptian poem, the “Teaching for Merikare”, culminates in a hymn to the creator god who asserts his care for suffering humanity (“When they weep, he is listening”), yet also portrays the creator as a stern father “slaying his son for the sake of his brother” . Suffering, even if it seems inexplicably harsh to humanity, thus serves a higher divine purpose, becoming the creator’s tool for chastising his errant creations’ behavior. [Source: Roland Enmarch, Liverpool University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship. org ]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

"Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume I: The Old and Middle Kingdoms" by Miriam Lichtheim and Antonio Lopriano (2006) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume II: The New Kingdom” by by Miriam Lichtheim and Hans-W Fischer-Elfert (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Literature of Ancient Egypt;: an Anthology of Stories, Instructions, and Poetry” translated by William Kelly Simpson (1972) Amazon.com;

“Echoes of Egyptian Voices: An Anthology of Ancient Egyptian Poetry” translated by John Foster (1992) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Proverbs (Tem T Tchaas)” by Muata Ashby (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Teachings of Ptahhotep: The Oldest Book in the World” by Ptahhotep (1987) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptian Wisdom Texts” by Muata Ashby (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Tale of Sinuhe and Other Ancient Egyptian Poems (1940-1640 BC” by 1997) Amazon.com;

“Writings from Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkerson (2016) Amazon.com;

The Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, Stelae, Autobiographies, and Poetry” by William Kelley Simpson, Robert K. Ritner, et al. (2003) Amazon.com;

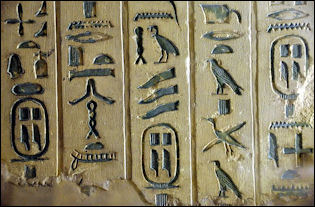

Variety and Expressiveness of Ancient Egyptian Writing

Andreas Pries wrote:Among the idiosyncratic aspects of ancient Egyptian life and culture, Egyptian writing has long received particular attention — not only in recent academic discourse, but already in Antiquity. Compared to other writing systems, hieroglyphs and, to a lesser extent, their cursive derivatives, hieratic and Demotic, demonstrate extraordinary potential to express different aspects of both meaning and sound when employed beyond their conventional use. [Source:Andreas Pries, University of Tübingen, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2023]

In its particular iconicity Egyptian writing, especially hieroglyphic writing, works even outside the framework of language and shares common features with Egyptian art. In the textual record non-standard creative writings highlight the potency and multidimensionality of Egyptian writing through the interplay of meaning, sound, and icon. The main characteristics of non-standard creative writings defined according to their varying forms and functions. In conclusion, a system of classification, as provided here, can further our understanding of the multitude of forms and functions involved, and thereby enhance appreciation of the potency of Egyptian writing.

Early Greek historians (or rather, ethnographers) and philosophers were captivated by the fact that different types of writing were in use in Egypt at the same time to serve different purposes and to function even in an iconic, extra-linguistic context. Particularly, although not exclusively, the hieroglyphic script and its strong iconicity (or rather, pictoriality; for the difference between the two categories, were main topics of interest.

The various scripts of genuine Egyptian origin all represent a logo-phonetic writing system that consists of phonetic, logographic, and classifier signs and thus combines the expression of meaning and sound. On that note, the use of hieroglyphs, hieratic, and Demotic is aimed at both the semantic and the phonetic notation of language. Furthermore, there is no fixed orthography for Egyptian words, nor is there a limited inventory of signs. Theoretically, an indefinite number of new or modified signs could be added to this open inventory as long as their meaning is more or less self-evident to their recipients. But custom and tradition had a strong impact on what writings were possible in any given context and at any given time, though besides these standard writings the use of variant and also unconventional spellings is widespread.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Egyptian Writing: Extended Practices” by Andreas Pries escholarship.org

Development of Ancient Egyptian Literature

With the exception of religious texts we know little of the literary conditions that existed before the time of the Middle Kingdom; several tales of that period have however come down to us, and the contents of these show that they were of popular origin. The Egyptians of the Middle Kingdom (2040–1782 B.C.) seem to have been especially fond of stories of travel, in which the hero relates his own adventures. Out of the half-dozen books which we possess of this period, two at least contain narratives of this kind, whilst we have not a single one of later date. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

In the New Kingdom (1570-1069 B.C.), instead of the subtle refinement which in previous times had predominated in light literature, the stories became quite simple both as regards their contents and their form. Nothing can be more homely than the tales of the New Kingdom with their monotonous though popular language destitute of all rhetoric and exaggeration. The subject of the most ancient of these stories, which, judging from the language, seems to have been written in the Hyksos' time, is connected with old historical incidents — incidents that had lived in the memory of the nation because the pyramids, the greatest monuments in the country, served ever to call them to mind.

The simplicity of the style, which distinguishes these stories of the New Kingdom from those of the Middle Kingdom, is also a characteristic of the later literature; evidently fashion had reverted to a great extent to the truth of nature. Yet we must not imagine this rebound to have been of a very deep nature, the books of the Middle Kingdom were always considered by scholars to be patterns of classical grace/ and in the official texts they imitated their heavy style and antique phraseology without producing, according to our opinion, anything very pleasing. A story like the above, simply related in the conversational manner of the New Kingdom, appeals to us far more than the elegant works of the learned litterateurs, who even when they made use of the spoken language, always believed themselves obliged to interlard it with scraps from a past age.

Hieroglyphic Texts

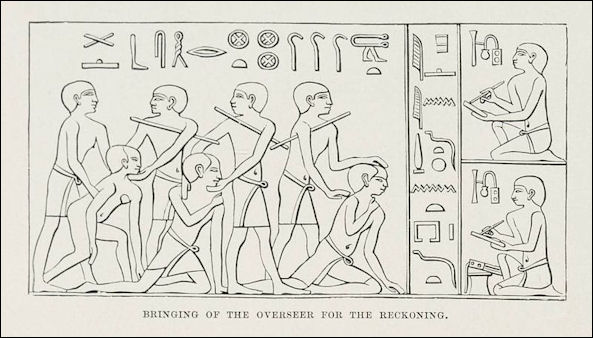

pyramid text Most documents and important information was written in papyrus texts. The hieroglyphics found on tomb walls and works of art tended to be formulaic and offered little information that wasn’t already known.

Three important papyrus texts have survived to this day are: “The Pyramid Texts” , “Book of the Dead” and the “ Coffin Text”. They consisted mostly spells intended to bring about salvation and comfort the dead in the next world.

Vanessa Thorpe wrote in The Observer, “The script of a papyrus is read from one side across to the other, depending on which way round the depicted animal heads are facing. The spells and incantations appear alongside the images they evoke and they commonly deal with the sort of problems faced in life, such as the warding off of an illness. They are usually rather straightforward: prose rather than poetry. "Get back, you snake!" reads one for protection against poisonous serpents. For the ancient Egyptians, the act of simply writing something down formally, or painting it, was a way of making it true. As a result, there are no images or passages in The Book of the Dead that describe anything unpleasant happening. Setting it down would have made it part of the plan. There was, however, always a heavy emphasis on dropping the names of relevant gods at key points along the journey.[Source: Vanessa Thorpe, The Observer, October 24, 2010]

A hymn to the god Amen with a prayer for the queen, written in around 1300 B.C., goes: "Prize from the Chief Wife of the King, his beloved...Nefertiti, living, healthy, and youthful forever and ever."

Ancient Egyptian Religious Texts and Myths

The Pyramid Texts are among the oldest texts. They were based on inscriptions of spells found in the burial chambers of the pyramids and dated to around 2600 B.C. They were like an early compendium on the Egyptian religion. The Amduat (“The Book of the Netherworld”) and The Book of the Dead are based on them. A typical spell from the Pyramid Texts went: “O Osiris, the King, may you be protected. I give to you all the gods, their heritages, their provisions, and all their possessions, for you have not died."

According to ancient Egyptian creation myth, before the world emerged from the waters of chaos the Sun god Ra appeared. He was so powerful that all he had to do was say the name of something and it came into being. "I am Khepera at the dawn, and Ra at noon and Tum in the evening," he declared and the first day was created. When he cried "Nut" the goddess of the sky took her place between the horizons. And when he the shouted "Hapi" the sacred river Nile began flowing through Egypt. After filling the world with beautiful things Ra said the words "man" and "women" and thus people were created. Ra then transformed himself into man, thus becoming the first pharaoh. [Source: Roger Lancelyn Green, Tales of Ancient Egypt]

The Osiris Story is one of the best-known Ancient Egyptian myths. Mark Smith of the University of Oxford wrote: “According to a widespread Egyptian tradition, the god Osiris was born in Thebes on the first epagomenal day, the 361st day of the year, asthe eldest child of Geb and Nut. Like other Egyptian deities, his hair was blue-black in color. He married his younger sister Isis, with whom he had initiated a sexual relationship while both were still in their mother’s womb, and was crowned king of Egypt. At the age of 28 the god was murdered by his brother, Seth. According to some sources, the killer justified his act with the claim that he had acted in self- defense. After the murder of her husband, Isis searched for and discovered his corpse, which was then reconstituted through mummification. Using her potent spells and utterances, she was able to arouse Osiris and conceive her son Horus by him. Thus a sexual relationship that began before either deity was actually born continued even after one of them had died. [Source: Mark Smith, University of Oxford, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

RELATED ARTICLES:

BOOK OF THE DEAD AND OTHER ANCIENT EGYPTIAN RELIGIOUS TEXTS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

BOOK OF THE DEAD TEXTS, HYMNS, RITUALS AND SPELLS africame.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN CREATION GODS AND MYTHS africame.factsanddetails.com

CREATION OF MANKIND AND THE MYTH OF THE HEAVENLY COW africame.factsanddetails.com ;

OSIRIS (GOD OF THE DEAD AND THE AFTERLIFE): MYTHS, CULTS, RITUALS africame.factsanddetails.com

Wisdom Literature in Ancient Egypt

Wisdom literature is a genre of literature common in the ancient Near East. It consists of statements by sages and the wise that offer teachings about divinity and virtue. The earliest known wisdom literature dates back to the middle of the 3rd millennium B.C. and originates in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. Much of wisdom literature can be broadly categorized into two types - conservative "positive wisdom" and critical "negative wisdom" or "vanity literature": In ancient Egypt, literature belonged to the sebayt ("teaching") genre of literature which flourished during the Middle Kingdom of Egypt and became canonical during the New Kingdom. Notable works of this genre include the “Instructions of Kagemni”, “The Maxims of Ptahhotep”, the “Instructions of Amenemhat, the Loyalist Teaching.

The author of one piece of wisdom literature is supposed to be a learned man and a wit; he calls himself a “proficient in the sacred writings, who is not ignorant; one who is brave and powerful in the work of the Seshat (goddess of wisdom)l a servant of the lord of th god Thoth in the house of the books. " He is “teacher in the hall of the books," and is “a prince to his disciples.” His opponent Nechtsotep has little to boast of in comparison with such advantages; he is indeed “of a wonderful good heart . . . has not his equal amongst all the scribes, wins the love of every one; handsome to behold, in all things he is experienced as a scribe, his counsel is asked in order to know what is most excellent," but with all these good qualities, he lacks that eloquence in which the author so greatly excels. The latter is able indeed to boast that “whatever comes out of his mouth is dipped in honey. " ° This superiority of his own style over that of Nechtsotep forms the chief subject of the book. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

"Thy letter reached me," writes the author to Nechtsotep, "just as I had mounted the horse that belongs to me, and I rejoiced and was glad over it. " His pleasure however was not of long duration, for on examining it more closely, he says: “I found it was neither praise nor blameworthy. Thy sentences confuse one thing with another, all thy words are wrong, they do not express thy meaning. It is a letter laden with many periods and long words. What thy tongue says is very weak, thy words are very confused; thou comest to mc involved in confusion and burdened with faults. " '

It seems that the author now intends to contrast this circumstantial misshapen letter with his answer; he wishes to show how Nechtsotep ought to have written, and for this purpose he repeats to him a part of his letter in more elegant form. He manages of course to take his choice out of the many rolls “Nechtsotep had sent, so as to be able at the same time to direct all manner of little sarcasms at his opponent. The latter had boasted of his warlike deeds, and described with pride his expeditions through Syria; in the author's repetition these deeds are also related, but as a rule rather ironically.

Before the author touches upon this subject which forms the main part of his book, he considers it necessary to defend himself from two personal attacks, which his friend had ventured to make against him. He had reproached him that he was a bad official, “with broken arm, and powerless. " The answer to this is: "I know many people who are powerless and whose a7'in is broken, miserable people with no backbone. And yet they are rich in houses, food, and provision. No one can thus reproach me. " Then he cites to him examples of lazy officials, who nevertheless have made a career, and as it appears are the good friends of his antagonist: he gives their names in full as proof The other attack is easier to parry; Nechtsotep had reproached him with being neither a scribe nor an officer, his name not being recorded in the list. “Let the books but be shown to thee," the author answers him, “thou wilt then find my name on the list, entered in the great stable of King Ramses H. Make inquiries onl}from the chief of the stable; there are incomings that are entered to m}name. I am indeed registered, I am indeed a scribe. " "

The author then begins the promised recapitulation of the deeds of Nechtsotep, the deeds of “that most excellent scribe, with an understanding heart, who knows everything, who is a lamp in the darkness before the soldiers and enlightens them. "-' He reminds him how well he had transported the great monuments for the king, and had quarried an obelisk 120 cubits long at Aswan,' and how afterwards he had marched to the quarries of Hammamat with 4000 soldiers that he might there “destroy that rebel. " '" Now however he is striding through Syria as a inahar, as a hero, a viaryna, a nobleman styling himself with pleasure b)these foreign titles. '' The author has here come to the subject which affords him the best opportunity for his raillery.

We see that, in the principal part of the book, the attack of the author on Nechtsotep merely consists in harmless teasing, and as a proof that he really does not mean to wound, he adds the following gracious conclusion to his epistle: “Regard this in a friendly manner, that thou mayest not say that I have made thy name to stink with other people. Behold I have only described to thee how it befalls a mahai; I have traversed Syria for thee, I have described to thee the countries and the towns with their customs. Be gracious to us and regard it in peace. " "

Thus our book closes. The kindest critic will scarcely maintain that it is distinguished by much wit, and still less will he be inclined to praise it for the virtues of clear description and elegant style. Yet in Egypt it enjoyed great repute, and was much used in the schools. What seems so prosy to us, appeared to the educated literary Egyptian of the time of the New Kingdom charming and worthy of imitation, “dipped in honey," to retain the strong expression of our author. The older books, all of which seem to date from the Middle Kingdom, are intended not only to teach wise living and good manners, but also to warn from a frivolous life; the instructions they contain are always couched in the following form: some ancient sage of former days — the great king Amenemhat I., or a learned governor of the Old Kingdom, imparts to his son as he is growing up the wisdom which has led him so happily through life. hven in their outward form these maxims show that they emanate from a man who does not care for idle chatter; they either approach the impossible in laconic expression, or they conceal thoughts under a multitude of illustrations, or again they are remarkable for the artificial composition of the sentences. An example of this obscure language, which as a rule is quite incomprehensible to us, has already been given in the earlier part of this chapter.

Recitation and Speech Acts in Ancient Egypt

Erika Meyer-Dietrich of the University of Uppsala in Sweden wrote: “Ancient Egyptian texts have been found with instructions on how they should be performed. Recitation, speech acts, and declamation are related to the action of speaking out loud in religious- ritual and juridical contexts, as well as for entertainment. Recitations are used in contexts that demand a correct wording or the power of words as utterance. Speech acts are performative or operative texts, which have an effect by being spoken out loud and result in a change of the persons or objects that are addressed by the text. Declamations are a performance of literary compositions to an audience. The basis on which texts can be considered as part of a recitation, speech act, or declamation are not only in-text terms but also indications of their performance- context, their localization in an accessible place, and their performance by an authorized person. [Source: Erika Meyer-Dietrich, University of Uppsala, Sweden, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Egyptian wisdom literature (such as the Instruction of Ptahhotep on Papyrus Prisse 5, 4 - 7) and narratives (the Tale of the Eloquent Peasant, for example) clearly establish the relationship between speaker and listener. The pronounced word is the heard one. It is through listening that knowledge is gained. Sinuhe is motivated to stay where he hears the Egyptian language. The importance of listening corresponds to the emphasis on language as a bond that connects speaker and hearer. The relationship involves people across gender borders and ontological borders. In addresses to the living, the deceased requests that the offering formula be read aloud. With the sound of their voice, visitors who read the formula give rise to the actual existence of that, which they are evoking for the benefit of the deceased. The relationship works on an ethical level. It integrates people into society.

“The Egyptian idea, which regards the word that leaves the speaker’s mouth as a creative act , conveys the belief that the spoken word is powerful. The word of the creator is communicated to the multitude (as we see in Coffin Texts I 325a, Book of the Dead 38: 2, and Stela Turin 1791). The asymmetry of the few who recite and the many who hear the recitation is emphasized in the Middle Kingdom (for example, in Stela Cairo CG 20017) and the Second Intermediate Period (see the inscription in Tomb el-Kab). “Raising the voice” (rdj xrw) announces someone’s arrival (such as we see in the Harper’s Song in Theban Tomb 178). This cultural attitude concerning the potential and the spread of the language justifies a perspective on texts as communicative acts that are orally performed.”

Recitation in Ancient Egypt

Erika Meyer-Dietrich of the University of Uppsala in Sweden wrote: “The concept of the spoken word as the perceived one is in line with the evaluation of pronunciation that is obvious in the rich use of recitation markers in the texts. A distinction between the pronounced word as such and declamation understood as skilled and professional recitation is unattainable. The Egyptian obsession with the written word can be observed in the scribes’ playful attitude in puns and alternative spellings. In the available source material, this is not matched by an apparent obsession with the way words have to be performed in the texts. The most valuable source for instructions on how to recite religious texts has survived in the Ptolemaic and Roman Book of the Temple (Quack 2002). According to this book, the children of high-ranking priests were trained in musical performance of hymns, appropriation of traditional texts (reciting by heart), and explanation of problems (comments). A “book of recitation after” is listed among the scriptures. The education of scribes who worked as magicians, teachers (jmj-r sbAw) in the House of Life, chironomists, music teachers (jmj-r Hsw), and religious specialists such as lecture priests or stolists (Hm-nTr) andthe Great of the Pure Ones (aA wabw), who recited the daily temple ritual, shows the importance of recitation in ritual. [Source: Erika Meyer-Dietrich, University of Uppsala, Sweden, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The scarce evidence of terms employed for techniques of recitation gives rise to a lexicographical problem regarding the audible dimension of words. 4dAdA (“to tremble (with the voice)”), suggested as tremolo, wSA (“to start singing”), and tjA (“to scream”) are mentioned in the Book of the Temple. Singing without instruments may indicate a rhythmic performance of lyrics, hymns, prayers, and laments as a kind of Sprechgesang. Njs (“to call”) is treated as reading aloud). 9sw (“to call”) and Snj nt-a (“to recite the ritual”) is, used for the recitation of spells.

“The weight that is put on the perception of words is not sufficient to classify texts as read in reality. This even applies to texts with recitational instructions or markers that clearly characterize them as recitation and to texts that are iconographically represented as spoken. Written markers that designate the text as words to be uttered are: Dd mdw (“to say words”), r-Dd (“in order to say”), and TAz (“spell”). Uninterrupted speech is indicated by Ddj (“to carry on without pausing”). Markers indicating that words have to be repeated in the same or in a reversed order are: zp 2 (“once again,” literally “twice”), Dd mdw 4 (“to be recited four times”), and TAz-pXr (“vice versa”). In tombs of private individuals, iconography provides an imagined speaker- situation for uttered words. Texts are accompanied by a representation of the speaker with a gesture of recitation. In tombs from the 5th - 11th Dynasty, the lecture priest holds the unrolled papyrus scroll. Sometimes the tomb owner is represented as the speaker. He is depicted as a man with one arm lifted up in invocation like the determinative A 26 in Gardiner’s sign list. The hand held to the mouth is a gesture of a call. When the speaker is introduced in the form of a picture or the first person pronoun, it is possible to understand the text recited in an appropriate context as ritual activity.

“Within their cultural context, the interaction on a symbolic level renders the pronunciation of words and their perception in no respect less real. A consequence of the imagined performance of texts that are located in inaccessible places is that the performance is congruous with the text. Performance is an activity that defines itself by being acted out. Imagined speech acts lack the discrepancy between text as prescript and recitation as acting. Therefore, a prerequisite for texts that can be suggested as part of a recitation is the possible discrepancy between text and performance constituted by the accessibility for the actor and the visibility of the text. To include recitation by heart reduces the condition for performance to accessible spaces. The locations can be exclusive, e.g., temples for the daily cult, tomb chapels, and the embalming hall, or public, e.g., procession routes on the occasion of religious festivals. In order to transfigure offerings, speech acts were performed in the temple and the necropolis. The recommendation in the Calendar for Good and Bad Days to “hurry and spend the day in a festive mood with spells” calls for recitations on the occasion of festivals. Biographies, Harper’s Songs, and funerary papyri mention in this context the recitation for the ba of a god as being advantageous. It is reasonable to assume that location and time for magical spells differed from the performance in public spaces. To cure a seriously ill individual, the spells must have been recited at any time and in any place, including private homes.”

Performative Speech Acts in Ancient Egypt

Erika Meyer-Dietrich of the University of Uppsala wrote: “Texts that were recited on a regular basis have survived, inscribed in temple walls and as papyrus documents. The most important papyri are the Ramesseum Dramatic Papyrus from the Middle Kingdom, the libraries that were attached to the temples from the Late Period, and magical papyri, the latest of them written in Greek. Ritual texts are multifunctional. In papyri for ritual use, different types of text can be combined: instructions, comments, narrative passages, and performative expressions. In view of the dimension of time, performative texts can be categorized as prescriptive, operative, and interpretative texts. Only the operative parts of ritual texts function as speech acts, that is, the words have the power to do things the very moment they are uttered. To be operative, words have to address somebody and do what they do because of their connotations that attach certain values to them. Prayers, hymns, and aretalogies addressing a god use a salutation, the second personal pronoun, names, titles, and epithets. [Source: Erika Meyer-Dietrich, University of Uppsala, Sweden, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Words as deeds act simultaneously on two levels. They work on the level of operative texts as performed and on the level of speech acts as activity in its own right, which is the change of the social or ontological status of the addressed persons and objects. Both activities are dialectically related. Expected results of acting by speech influence how speech acts are performed. A possible criterion to distinguish operative texts from non-operative texts is that ritual as activity constitutes itself as different and in contrast to other activities. Roeder puts forward the criterion of semantic power to create a ritual environment that is believed to exist. According to Egyptian terms, three different operative text-types can be discerned: 1) the sAx (“to transfigure”), which indicates the effect of speech acts to transform the addressee into a person who can act, or a profane object into a religious one by recitation; 2) protective and therapeutic spells to save from harm or cure the addressee and curse the enemy; and 3) sHtp (“to satisfy”), which are hymns to appease the addressee.

“A religious-ritual or juridical setting is a plausible scenario for speech acts. In the Coffin Texts, the perception of words confirms a successful illocutionary act. Statements like “my words have been heard” legitimate the deceased. The reference to words that were heard in trial or before the tribunal of the gods shows that, like the religious-ritual, also a juridical context is supposed to render a quotation functional and authentic as a speech act. Non-religious recitations may have been uttered in the court of law, which took place in “the gate of justice.” As religious or juridical activity, recitation has to be performed by specialists who embody the required practical knowledge and who are endowed with the power to do what they are doing. A condition for operative speech in regard to the situation is a cultural convention that agrees on the criteria for persons who are authorized to recite words in a certain context. The power to act is referred to and thereby reproduced in the speech act itself as the performer’s self- representation in the daily temple ritual. The power is institutionalized. It sanctions priests to take on the role of a divine being on the occasion of festivals, to recite formulae in the ritual of embalming and for the funeral, and to read liturgies for a deceased individual during lunar feasts and other calendrical festivals. It permits scribes and magicians to pronounce spells that affect the cause of life or cure somebody.

“The ritual knowledge required in terms of competence and performance classifies recitation both as ritual practice and as performing art. It demands a state of purity, preparation for the act itself, speaker competence, and ritual mastery. The state of purity is described in the Book of the Dead and on stelae: “One has to recite the spell clean and pure, not having approached women and not having eaten small cattle or fish” The special preparation for the speech act is the purification of the mouth and, according to one source, also the ears; they were purified with salt or with incense. Speaker competence includes “ritualization,” which means the use of language as speech act in a ritual.”

Ritualization in Ancient Egypt

wo priests, one with a papyrus roll, the other with a vase for libations

Erika Meyer-Dietrich of the University of Uppsala wrote: “Ritualization forms texts to distinguish them from daily spoken language. This can be done by using an archaic type of language for religious texts. It explains the appearance of Late Middle Egyptian, also called égyptien de tradition, that coexisted with later Egyptian for more than a millennium. Ritualization is the structuring of recited texts in a rhythmic manner by employing the language’s natural rhythm, caesuras, alternating speakers, choral passages, and refrains. Moreover, speaker competence includes the knowledge of the ritual language, intimacy with the use of language, the range of meaning attached to words in a ritual, and their possible connotations. The speaker embodies a practical knowledge of how to perform the ritual. Recitation as ritual practice is the capability to put forward expected values that are attached to words. This is accomplished by positioning them first in the text, accompanying them with gestures for recitation, singing them, or reading them in an appropriate manner according to situation, purpose, and intended effect. [Source: Erika Meyer-Dietrich, University of Uppsala, Sweden, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“A connotational device of positioning, called “honorific anticipation,” is testified in writing. Signs and names referring to the divine or royal sphere precede the rest of the sentence independent of their actual syntactic position to express a cultural attitude vis-à-vis the person it represents. The question arises whether such a cultural attitude is exclusively graphic or can be assumed for oral performance. Ritual practice is using words in a way that highlights or minimizes certain inherent aspects by means of stress, tone, pitch, lengthening, pauses, and rhythm. While the investigation of such audible resources must remain hypothetical, the researcher should keep them in mind. Connecting ritually performed speech acts with other activities in the ritualization process synchronizes them with the ritual environment. Therefore, correct timing is essential for the act itself to work in the intended manner.

“Ritual mastery is the ability “to take and remake schemes from the shared culture that can strategically nuance, privilege or transform”. This allows ritual specialists to pronounce texts unmodified or to give them subtle nuances. The relationship between historical developments in ritual discourse and performance causes minor changes, e.g., of personal pronouns in texts. These changes may support their actual performance. Developments in the spoken language and changes in cultural conceptions influence ritual recitation. One example is the change in the use of ritual language that appeared during the reign of Thutmose III.”

Declamation of Literature

Erika Meyer-Dietrich of the University of Uppsala wrote: “Except for ritual speech acts, literature is the type of texts that were probably recited in ancient Egypt. The sources comprise tales, travel narratives, dialogs, teachings, and poetry. Isolated calls and speaker labels that are included in a wider concept of narratology are not part of a recitation. No archaeological finds testify to reading in public or private circles. However, several circumstances promote the assumption that literary texts were performed orally. They are comprehensively investigated in Parkinson’s treatment of Middle Kingdom literature as social practice. The word Sdj (“to recite”) is used for ritual texts, spells, letters, and biographies, implying a declamatory method of delivery. The style of literary compositions reflects a performative oral setting. However, it is not clear whether these characteristics of text composition testify to the performance of texts or otherwise. Written in order to be heard, the author may invent a fictive audience for the text. [Source: Erika Meyer-Dietrich, University of Uppsala, Sweden, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Red Chapel detail

“The criteria of visibility and accessibility for recited texts also apply to literature. Within their fictional framework, literary compositions are enacted communication. In contrast to ritual texts, declamation of literature is not operative as performative speech in the sense that the words uttered do things. Their performance is limited to the level of words that are delivered in a declamatory manner. The second level of speech acts as activity in its own right is not relevant to literature. Literary performance also differs in its time dimension. In contrast to future-oriented speech acts, the performance of literature is retrospective. Narratives tell something that has taken place. In teachings, things that have yet to happen are presented as consequences.

“In the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.), structuring points mark the rhythm of speech. In the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.), paragraph markers, units of thought—also called parallelismus membrorum or thought couplets, which is the use of language in its natural rhythm in the sense of structuring a narrative —metrics, and devices for a poetic style indicate the rhythm of speech. The performer combines the customary use of language with a sensitivity of reading that is discernible in how he follows the plotline. The performance of literature in an elite context is attainable in the prologue to the Tale of the Eloquent Peasant. Evidence for told folklore is scarce. Educated scribes were the storytellers. Other professions that are trained in rhythmic performance of texts, e.g., singers, chironomists, and priests, cannot be excluded as possible performers of literary compositions. Among the holdings of the temple library of Tebtunis were teachings and narratives. In the Myth of the Sun’s Eye, the god Thoth in his shape as a baboon tells stories to appease and to entertain Tefnut. It has been suggested that the lines written with red ink and the remark xrw.f m-mjtt (“his voice likewise”) instruct the storyteller to use the same intonation every time the baboon is speaking.

“The narrator tells literary works as entertainment or moral instruction. For that purpose, the language, colloquial or elevated, functions as rhetoric resource for the storyteller or lecturer. A rhetorical element that is discernible in literature is dialectical positions. The partners in the fictive dialogs are named. The author introduces a following recitation by “he says.” Often he also mentions the listener in a dialog with “he said to me.” In the Middle Kingdom, examples of speech that are not introduced by such a remark are rare. The introductory remark “NN says” appears seventy times in Papyrus Westcar. The story takes place in a scenario that the listener recognizes.

“An introductory remark, for example, sDd.j (“I shall tell you”), introduces the narrative passages in the Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor and anchors the story in the moment when it is told. The quoted passages raise the empathy of the listeners. The choice of citations or sayings increases familiarity. Enclitic particles and exclamatory devices address an audience. Devices that raise the listener’s empathy in performance are the style of literary compositions, refined language, and means of articulation, e.g., emphatic constructions and topicalization.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024