Home | Category: Language and Hieroglyphics

HIEROGLYPHICS

Hierogliphics Stela of Nemtiui Egyptian writing in the form hieroglyphics is associated most with inscriptions and writing on tomb and temple walls. Hieroglyphics function as both logograms (signs representing things or ideas) and phonograms (pictured objects represented sounds, similar to letters in an alphabet). They also served as word-signs (signs which stood for entire words) and syllabic signs (signs which stood for syllables). In Egyptian times syllables were not grouped into a single word as they are in English today. They were written separately as were words and thus sometimes distinguishing between a word and a syllable of a word was difficult. There were no hieroglyphic vowels.

Hieroglyphics primarily represented the formal and ceremonial language for the pharaohs. They appeared on everything: paintings, obelisks, temple walls, coffins, tombs, documents, perfume containers. An estimated one third of the 110,000 Egyptian pieces in the British Museum have writing on them.

Simon Singh of the BBC wrote: “Hieroglyphs dominated the landscape of the Egyptian civilisation. These elaborate symbols were ideal for inscriptions on the walls of majestic temples and monuments, and indeed the Greek word hieroglyphica means 'sacred carvings', but they were too fussy for day-to-day scribbling, so other scripts were evolved in Egypt in parallel. These were the 'hieratic' and 'demotic' scripts, which can crudely be thought of as merely different fonts of the hieroglyphic alphabet. [Source: Simon Singh, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “Hieroglyphs were called, by the Egyptians, “the words of God” and unlike the simple elegance of modern writing systems, this early attempt at recording words, used a number of techniques to convey meaning. The picture symbols represent a combination of alphabet and syllabic sounds together with images that determine or clarify meaning and depictions of actual objects which are the spoken word of the thing they represent. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

“All writing systems probably evolved in this way but their original forms were lost as pictures were refined to a simple abstraction making writing an efficient tool for day to day business. Indeed, the ancient Egyptian Hieratic script served this function but the Egyptians deliberately preserved Hieroglyphs, in their original forms, because they believed them a gift from the gods which possessed magical powers. So they inscribed them on temple walls, tombs, objects, jewellery and magical papyri to impart supernatural power not for mundane day to day communication. The script was developed about four thousand years before Christ and there was also a decimal system of numeration up to a million.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs” by James Peter Allen (2000) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs: A Practical Guide” by Janice Kamrin (2004) Amazon.com;

“How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs” by Mark Collier (1998) Amazon.com;

“Hieroglyphs Without Mystery” by Karl-Theodor Zauzich (1992) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Hieroglyphs for Complete Beginners: The Revolutionary New Approach to Reading the Monuments” by Bill Manley (2012) Amazon.com;

“Hieroglyphic Dictionary: A Vocabulary of the Middle Egyptian Language” by Bill Petty (2012) Amazon.com;

“Illustrated Hieroglyphics Handbook” by Ruth Schumann Antelme (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Story of Writing: Alphabets, Hieroglyphs & Pictograms” by Andrew Robinson Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Language and Writing: The History and Legacy of Hieroglyphs and Scripts in Ancient Egypt” by Charles River Editors (2019) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Hieratic Texts; 1: 1 by Sir Alan Henderson Gardiner (1879-1963) Amazon.com;

“A Miscellany of Demotic Texts and Studies (The Carlsbert Papyri, 3)”

by Paul John Frandsen and Kim Ryholy (2000) Amazon.com;

Earliest Hieroglyphs

Hieroglyphics appeared about 5,200 years ago, about the same time as cuneiform writing emerged in Mesopotamia. "German excavations at Abydos in Egypt have revealed hieroglyphic inscriptions from [circa] 3200 B.C.," James Allen, a professor emeritus of Egyptology at Brown University, told Live Science. Similarly, Ludwig Morenz, an Egyptology professor at the University of Bonn in Germany, told Live Science that Egyptian hieroglyphs were created "around 3300/3200 B.C.." Allen said "the hieroglyphic system first appears pretty much fully formed, either because its beginnings were inscribed on perishable materials [that have not survived] or because it was invented by an unknown genius."[Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science February 13, 2024]

The earliest Egyptian hieroglyphics are among the written languages that have not been deciphered. Others include are the Minoan language of Crete; the pre-Roman writing from the Iberian tribes of Spain; Sinaitic, believed to be a precursor of Hebrew; Futhark runes from Scandinavia; Elamite from Iran; Mohenjo-Dam, the language of the ancient Indus River culture; and Archaic Sumerian, the earliest written language in the world."

Why Were Hieroglyphs Invented?

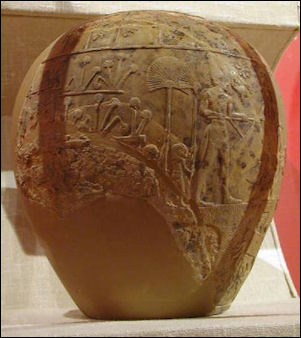

scorpion mace Why hieroglyphs were invented is a source of debate, Marc Van De Mieroop, a history professor at Columbia University, wrote in the second edition of his book "A History of Ancient Egypt" According to Live Science: At the time hieroglyphs were invented, Egypt was unifying into a single state and administration may have been a reason for their invention. It "is logical that a state of Egypt's size and complexity required a flexible system of accounting that could keep information on the nature of goods, their quantities, provenance and destination, the people in charge of them and the date of transaction," Van De Mieroop wrote in his book. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science February 13, 2024]

Another theory is that hieroglyphs were invented to help glorify gods and the king, Van De Mieroop wrote, noting that some early carvings showing kings contain hieroglyphs. "The glorification of the king may have been one of the driving forces in the script's invention," he wrote.

The Sumerians and Babylonians used their writing system primarily to keep records. Writing for the Egyptians took on more of religious role. Judging from the inscriptions and papyrus scrolls that have survived until today most texts dealt with spiritual matters and spells. The walls of tombs often featured more predictions of the dead's future life than records of historical events in his past life.

Hieroglyphics used in tomb paintings and religious objects were believed to be imbued with spiritual power. Many hieroglyphics were painted green because green represented youth, rebirth, spring, swamps, vegetation and resurrection. Sometimes hieroglyphic animals were depicted with disembodied heads or legs so that when they came alive in the afterworld they could not harm the pharaoh or his magic.

History of Hieroglyphics

Proto-hieroglyphics first appeared in 3400 B.C. in the form of stick figures inscribed in stone. The origin of this ancient form of writing remains a mystery and how drawing veered towards abstraction and became hieroglyphics is also not known. Artists often played with the appearance of the figures.

Hieroglyphic-style writing predating hieroglyphics was found in present day Israel in the 1930s. Many scholars believe that alphabet (with symbols representing sounds) was invented in Canaan and was introduced to Egypt, perhaps by Hebrew slaves working in mines in Egypt.

Egyptian writing during the Old Kingdom (2686 to 2125 B.C.) was used primarily for titles, epithets and bureaucratic records. There are virtually no Old Kingdom records of history, myths, legends or everyday life. Most of these things have been surmised from interpretations of tomb paintings and hieroglyphics, and texts written as many as 2000 years later.

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “Unlike other cultures the early picture forms were never discarded or simplified probably because they are so very lovely to look at. Hieroglyphs were called, by the Egyptians, “the words of God” and were used mainly by the priests. These painstakingly drawn symbols were great for decorating the walls of temples but for conducting day to day business there was another script, known as hieratic This was a handwriting in which the picture signs were abbreviated to the point of abstraction. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

Demise of Hieroglyphs

Hierogliphics The last known hieroglyphics were engraved in August 24, 394 on the Gate of Hadrian on the Nile island of Philae. According to the University of Memphis in Tennessee by that time, other writing systems such as Coptic were being used in Egypt. Knowledge of how to read and write hieroglyphs was lost and it wasn't until the 19th century, with the decipherment of hieroglyphs, that they were read again. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science February 13, 2024]

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “In AD 391 the Byzantine Emperor Theodosius I closed all pagan temples throughout the empire. This action terminated a four thousand year old tradition and the message of the ancient Egyptian language was lost for 1500 years. It was not until the discovery of the Rosetta stone and the work of Jean-Francois Champollion (1790-1832) that the Ancient Egyptians awoke from their long slumber. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Simon Singh of the BBC wrote: “Towards the end of the fourth century AD, within a generation, the Egyptian scripts vanished. The last datable examples of ancient Egyptian writing are found on the island of Philae, where a hieroglyphic temple inscription was carved in AD 394 and where a piece of demotic graffiti has been dated to 450 AD. The rise of Christianity was responsible for the extinction of Egyptian scripts, outlawing their use in order to eradicate any link with Egypt's pagan past. [Source: Simon Singh, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“The ancient scripts were replaced with 'Coptic', a script consisting of 24 letters from the Greek alphabet supplemented by six demotic characters used for Egyptian sounds not expressed in Greek. The ancient Egyptian language continued to be spoken, and evolved into what became known as the Coptic language, but in due course both the Coptic language and script were displaced by the spread of Arabic in the 11th century. The final linguistic link to Egypt's ancient kingdoms was then broken, and the knowledge needed to read the history of the pharaohs was lost. |::|

“In later centuries, scholars who saw the hieroglyphs tried to interpret them, but they were hindered by a false hypothesis. They assumed that hieroglyphs were nothing more than primitive picture writing, and that their decipherment relied on a literal translation of the images they saw. In fact, the hieroglyphic script and its relatives are phonetic, which is to say that the characters largely represent distinct sounds, just like the letters in the English alphabet. It would take a remarkable discovery before this would be appreciated. |::|

Linear Hieroglyphs

Lucía Díaz Iglesias-Llanos wrote: Linear hieroglyphs formed a script comprising signs that maintained the iconic power of hieroglyphs but were more schematically written. Although they are attested from as early as the Old Kingdom, they became visually distinct from other writing types only from the Middle Kingdom onward. This script was restricted to specific functions and contexts, mainly related to the ritual and funerary domains. Linear hieroglyphs displayed specific traits and conventions in the forms of the signs (covering a wide spectrum of formality, iconicity, and embellishment) and the layout of the texts (with an arrangement that favored columns of rightward-facing signs that were to be read in a retrograde manner). They had the added values of prestige and expense and were often indexical of temple manuscripts. There is an urgent need to compile repertoires of linear hieroglyphs to help further define aspects such as forms of signs, regional variety, historical changes, technological issues, and the influence of other Egyptian scripts. [Source: Lucía Díaz Iglesias-Llanos, Estudió Historia en la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2023]

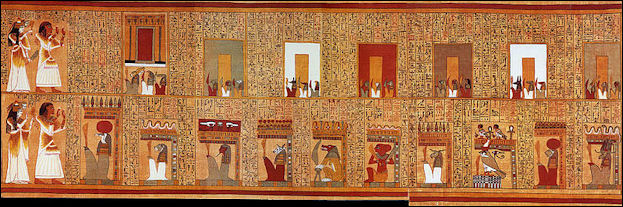

By the time of the joint reign of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III in the 15th century B.C. , linear hieroglyphs dominated Book of the Dead productions, replacing the hieratic script that had been used for the earliest examples of the late Second Intermediate Period and early New Kingdom on coffins and shrouds. The association of linear hieroglyphs with this corpus of funerary literature was so intense that this script has been traditionally called Totenbuchschrift in the academic literature. In fact, linear hieroglyphs found their most extensive use on papyri decorated with spells. The publication of Book of the Dead sources of the Theban recension has grown considerably in the last few decades.

Book of the Dead

During the early New Kingdom, royal burial chambers were sometimes decorated with the Amduat and the Litany of Ra, displayed on the walls with linear hieroglyphs and stick-like figures mimicking an unrolled papyrus. The choice of script might have been indicative of ancient “secret” papyri. Moreover, the preliminary versions of the texts copied in some tombs in the Valley of Kings were executed in red with signs akin to linear hieroglyphs, while more detailed hieroglyphic graphemes were written on top of them with black ink and later carefully carved out. In the New Kingdom, master copies used for transferring compositions onto the walls of tomb chambers decorated with linear hieroglyphic texts, and in some cases also with monumental hieroglyphs, were most likely written in linear hieroglyphs.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Linear Hieroglyphs” by Lucía Díaz Iglesias-Llanos, escholarship.org

Reading Hieroglyphics

Hieroglyphic symbols are pleasing to the eye but difficult to understand. They also took scribes a lot of effort to make. Texts written with them are generally tedious religious hymns, tomb wall inscriptions, or lists of a rulers achievements. Texts written on papyri in hieratic — a less time-consuming cursive writing used by pharaohs alongside cursive hieroglyphs and primarily written in ink with a reed brush on papyrus — are often much more interesting.

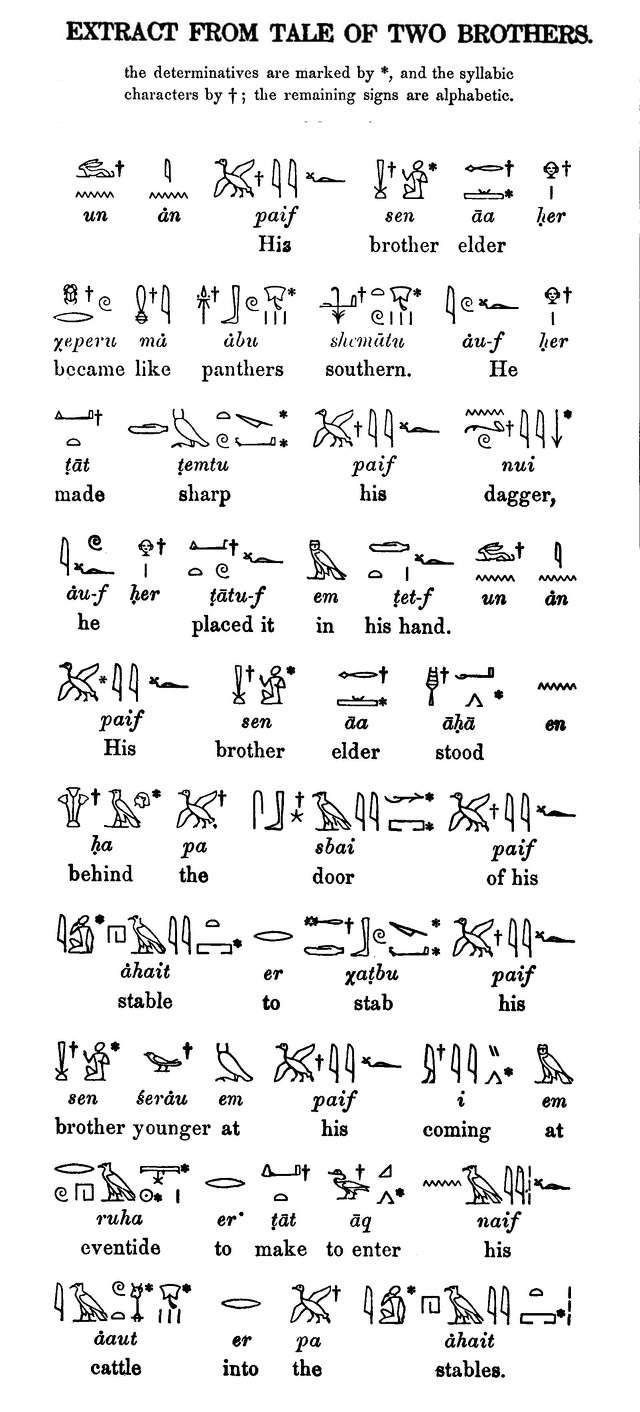

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “Hieroglyphs are written in rows or columns and can be read from left to right or from right to left. You can distinguish the direction in which the text is to be read because the human or animal figures always face towards the beginning of the line. Also the upper symbols are read before the lower. Alphabetic signs represent a single sound. Unfortunately the Egyptians took most vowels for granted and did not represent such as ‘e’ or ‘v’. So we may never know how the words were formed. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

“Syllabic signs represent a combination of two or three consonants. Word-signs are pictures of objects used as the words for those objects. they are followed by an upright stroke, to indicate that the word is complete in one sign. A determinative is a picture of an object which helps the reader. For example; if a word expressed an abstract idea, a picture of a roll of papyrus tied up and sealed was included to show that the meaning of the word could be expressed in writing although not pictorially. ^^^

“Ancient Egyptian history covers a continuous period of over three thousand years. To put this in perspective – most modern countries count their histories in hundreds of years. Only modern China can come anywhere near this in terms of historical continuity. Egyptian culture declined and disappeared nearly two thousand years ago. The last vestiges of the living culture ceased to exist in AD 391 when the Byzantine Emperor Theodosius I closed all pagan temples throughout the Roman Empire.

Hieroglyphic Alphabet and Grammar

The hieroglyphic alphabet contains 24 letters and includes: a vulture for the "A" sound; a leg for "B"; a water line for "N"; a winged seed for "I"; and an owl for "M"; a snake for "dj"; a horned viper snake for "F"; and a basket with a handle for "K." There were no hieroglyphic vowels.

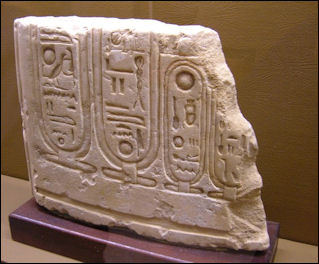

Hieroglyphic texts are filled with titles and names. For example a walking duck followed by a circle with a bull’s eye means "son of [the sun god] Ra." This combination of symbols often preceded the name of a pharaoh.

Various combinations of symbols can represent objects, pronouns, possessive pronouns and question words. Some hieroglyphic letters serve as prepositions: The owl can represent "of" or "with"; the water line can represent "to" or "for." Other hieroglyphic letters can represent personal pronouns. A horned snake can be "he," "him," "his" and "it" and a basket with a handle can represent "you."

Use of Symbols in Hieroglyphics

Hieroglyphs are said to have been invented by the Egyptian god Troth. In spite of the complexity of ancient Egyptian languages, basic hieroglyphic writing is one easiest of all the forms of ancient writing to read. Nevertheless the Egyptians were not content with this simple system. Even in prehistoric times they developed it in quite a peculiar manner. They endeavored to make the language clearer and more concise by the introduction of word symbols.

In order to express the word nefer (lute) normally three letters would be neccssary, but for the sake of simplicity they drew the lute itself instead of writing the three consonants; the advantage of the latter plan was that the reader knew exactly what word was meant, which was not so apparent if a picture was drawn and it was it not clear what the picture represented.

A great number of picture signs were introduced into the writing, giving the hieroglyphs their peculiar character. In many cases they have quite superseded the purely phonetic writing of the word. Then the Egyptians went a step further a put pictures into phrases or words. For instance to write “homeowner” the house itself was always drawn with other symbols.

There were also a great number of words which could not be drawn such as “son” or “to go out”. With these substituted words with a similar sound which could be easily drawn were often used. For example the word “son. was replaced “sa” (the goose) because it wasy to wrote. The word for son occurred much more frequently than goose. Many short words, the signs for which were used in other words, lost their meaning and became mere syllabic signs which could be employed in any word in which that syllable occurred.

In picture-writing of this kind it was impossible to guard against all misunderstandings, and the reader might often feel doubtful as to what idea was intended by a certain sign. For instance, with the sign of the ear, it might be impossible to know whether it stood for “masd'rt” (ear), or for “sod'm” (to hear), or 'odn, to substitute. It was was used as a sign for all these words. Whether a sign was to be used for the whole word, whether consonants were to be added, or how many of these there ought to be, was decided in each word by custom. “Hqt” (beer) was written phonetically only, whilst “hqat” (dominion) was written with the sign for the word and the two terminal consonants.

Determinatives in Hieroglyphics

The hieroglyphic language also contains determantives, which aided in specifying the meaning of words and, when grouped with other letters or symbols have a specific meaning. These include a symbol for a man, a fish, an ax and a tree. Determinatives with a phonetic sound include a walking duck (the sound "SA"), a flying duck (the sound "PA"), eye ("IR"), scarab ("KHpR") and ANKH.

The Egyptians wrote, like nearly all the nations of antiquity, without any division of the words, and there was therefore the danger of not recognising the words aright. It would be possible, for instance to read one particular group of signs as “ro H” (the mouth of) or masd'rt (the ear), or mes art (“born of the bird”) or “cJia” signifying two flowers. This danger was avoided in a most ingenious manner. At the end of the various words were added the so-called determinatives, signs indicating the class of idea to which the words belonged. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Thus after all words signifying man, they wrote, after those in which the mouth was concerned QTj, after abstract ideas r —, and so on. All ambiguity was thus avoided. If after there followed QAaLit would signify name; T with ""xO signified night, because there followed the determinatives of the sky and the sun; and “Txo” j. was determined with certainty by the figure of the ear to be the word inasd'crt, the ear.

These determinatives are the latest invention of Egyptian writing, and we are able to observe their gradual introduction; in the oldest inscriptions they are used but rarely, whilst in later times there is scarcely a word which is not written without one or even several determinatives. Which determinative ought to belong to a certain word, or in which line it ought to be written, is again decided by custom.

Altogether there were about 500 signs in general use When the orthography or the various words has been learnt by practice, it is easy to read a hieroglyphic text. The determinative shows throughout how the words are divided, and it enables us also at the first glance to recognise approximately with what sort of word we have to do. We must not underestimate this advantage in a language where the vowels are usually omitted.

Decorative Hieroglyphics

The appearance of the hieroglyphs is also much more pleasing than that of the cuneiform; when the signs are careful!y drawn and colored with their natural colors, they present an aspect both artistic and uplifting.

Broad spaces of architecture were often brightened up by this form of decoration, and we may even say that most of the inscriptions on the walls and pillars of the Egyptian buildings are really purely decorative. This is the reason of the empty character of the contents of these inscriptions; with the object of decorating the architecture with a few lines of brightly-colored hieroglyphs, the architect causes the gods to be assured for the thousandth time that they have put all countries under the throne of the Pharaoh their son, or he informs us a hundred times that his Majesty has erected this sanctuary of good eternal stones for his father the god.

It is evident, from the carefulness with which the Egyptians considered the arrangement and order of the hieroglyphs, that they regarded these monumental inscriptions chiefly as decorative. It is an inviolable law in Egyptian calligraphy that the individual groups of hieroglyphs forming the inscription must take a quadrangular form.

Desire for decorative effect is seen in the fact that when two inscriptions are placed as pendants to each other, the writing runs in opposite directions. As a rule the characters run from right to left, so that the heads of the hieroglyphs look towards the right; in the above case however the signs in the inscription on the right have to be content with following the reverse direction.

The ornamental character of hieroglyphics was in no way an advantage for the sense; the scribe, when making his pretty pictures, forgot only too easily that the individual signs were not ornamental. but that they had a certain phonetic value. The indifference to faults which thus arose was increased by another bad peculiarity of Egyptian writing. The frequent use of signs for whole words, which was allowed by the language, rendered the scribe more and more indifferent to the use of an insufficiency of phonetic signs.

Hieroglyphic Texts

Most documents and important information was written in papyrus texts. The hieroglyphics found on tomb walls and works of art tended to be formulaic and offered little information that wasn’t already known.

Three important papyrus texts have survived to this day are: “The Pyramid Texts” , “Book of the Dead” and the “ Coffin Text”. They consisted mostly spells intended to bring about salvation and comfort the dead in the next world.

Vanessa Thorpe wrote in The Observer, “The script of a papyrus is read from one side across to the other, depending on which way round the depicted animal heads are facing. The spells and incantations appear alongside the images they evoke and they commonly deal with the sort of problems faced in life, such as the warding off of an illness. They are usually rather straightforward: prose rather than poetry. "Get back, you snake!" reads one for protection against poisonous serpents. For the ancient Egyptians, the act of simply writing something down formally, or painting it, was a way of making it true. As a result, there are no images or passages in The Book of the Dead that describe anything unpleasant happening. Setting it down would have made it part of the plan. There was, however, always a heavy emphasis on dropping the names of relevant gods at key points along the journey.[Source: Vanessa Thorpe, The Observer, October 24, 2010]

A hymn to the god Amen with a prayer for the queen, written in around 1300 B.C., goes: "Prize from the Chief Wife of the King, his beloved...Nefertiti, living, healthy, and youthful forever and ever."

Difficulty Deciphering Hieroglyphics

Deciphering ancient written texts such as hieroglyphics can be a Sisyphean undertaking. Hieroglyphic writing contains signs that represent sounds and other signs that represent ideas said James Allen, an Egyptology professor at Brown University. Up until the scholar Jean-François Champollion (1790-1832) started studying hieroglyphs, "scholars basically believed that all hieroglyphs were only symbolic" Allen told Live Science, noting that Champollion's most important "contribution was to recognize that they could also represent sounds." [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, August 14, 2021]

"There are basically three kinds of decipherment problems," Allen told Live Science. Egyptian hieroglyphic writing falls into the category of a case in which "the language is known, but not the script," said Allen. Put another way, scholars already knew the ancient Egyptian language from Coptic, but did not know what the hieroglyphic signs meant.Another decipherment problem is where "the script is known, but not the language," Allen said. "Examples are Etruscan, which uses the Latin alphabet, and Meroitic, which uses a script derived from Egyptian hieroglyphs. In this case, we can read the words, but we don't know what they mean," Allen said. (The Etruscans lived in what is now Italy, and the Meroitics lived in northern Africa.) The third type of decipherment problem is where "neither the script nor the language are known," Allen said, noting that an example of this is the Indus Valley script from what is now modern-day Pakistan and northern India, as scholars don't know what the script is or what language it represents.

There are a number of lessons that scholars working on undeciphered scripts can learn from the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs. "One of the main theses of our book is that it's generally better to consider an ancient script in its cultural context," said Diane Josefowicz, a writer who holds a doctorate in science history and co-authored the recently published book "The Riddle of the Rosetta: How an English Polymath and a French Polyglot Discovered the Meaning of Egyptian Hieroglyphs" (Princeton University Press, 2020). Josefowicz noted that Thomas Young (1773-1829), a British scientist who also tried to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs, "approached the decipherment like a crossword puzzle because he didn't really care about ancient Egypt," Josefowicz told Live Science. "Champollion was much more interested in Egyptian history and culture, and because of this he was one of the first to make extensive use of Coptic, a late form of ancient Egyptian, in his study of hieroglyphics," Josefowicz said.

Being able to relate an undeciphered script to a language or language group is vital, Stauder added. Champollion needed to know Coptic in order to understand Egyptian hieroglyphs, said Stauder, who noted that scholars who deciphered ancient Mayan glyphs used their knowledge of modern Mayan languages while deciphering the glyphs.Stauder noted that scholars who are trying to decipher Meroitic are making more progress because they now know that it is related to the Northeast Sudanese language family. "The further decipherment of Meroitic is now greatly helped by comparison with other languages from the Northeast Sudanese and the reconstruction of substantial parts of the lexicon of proto-Northeast-Sudanese based on the currently spoken languages of that family" Stauder said. Maitland agreed, saying, "languages that still survive but are currently under threat could prove crucial to progress with still undeciphered ancient scripts."

Rosetta Stone — the Key to Deciphering Hieroglyphics

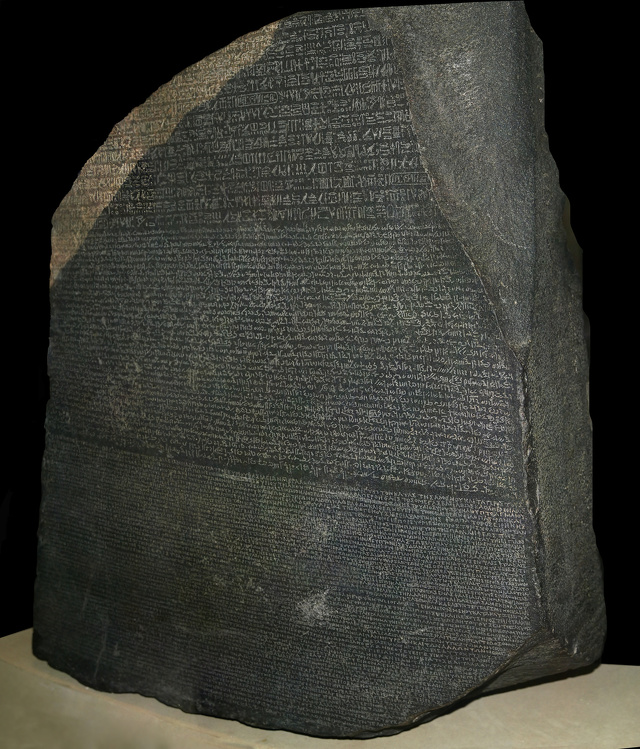

The Rosetta Stone is a black basalt slab 114 centimeter (45 inches) high and 74 centimeters (29 inches) wide. Inscribed in three languages: 53 lines of Greek, 32 lines of demotic (a cursive script used by the Egyptians between the seventh century B.C. and the A.D. fifth century) and 16 lines of hieroglyphics. Both the demotic script and hieroglyphics were initially indecipherable. It was written by a group of priest assembled in Memphis to mark the ascension to the throne of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes in 190 B.C. and carried a Memphis decree concerning the cult of the king.

The Rosetta Stone was unearthed in August 1799 by French soldiers, excavating ruined Fort Rachid near the town of Rosetta at the mouth of the Nile. Around the time the stone was found France went to war with Britain. When the French were forced out Egypt the stone fell into the hands of the British and was taken to the British Museum in 1802, were it remains today. Egypt wants the Rosetta Stone back.

The Rosetta stone was key to deciphering ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs but it took more than 20 years to translate it. The Frenchmen Jean-Françious Champollion (1790-1832) is given credit with the deciphering the hieroglyphics using the Greek on the Rosetta Stone. Champollion became aware of the Rosetta Stone when he was 12 and, the story goes, he became obsessed with deciphering it. Before he reached the age of 20 he had mastered Arabic, Syriac, Hebrew, Latin and Coptic (a language related to ancient Egyptian).

See Separate Article: Rosetta Stone africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024