Home | Category: Themes, Early History, Archaeology / Language and Hieroglyphics

ROSETTA STONE

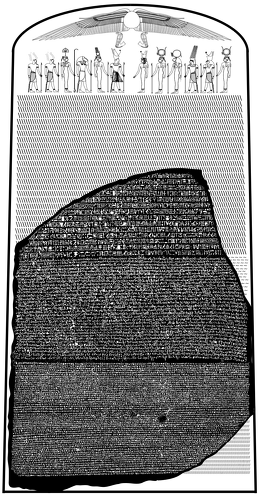

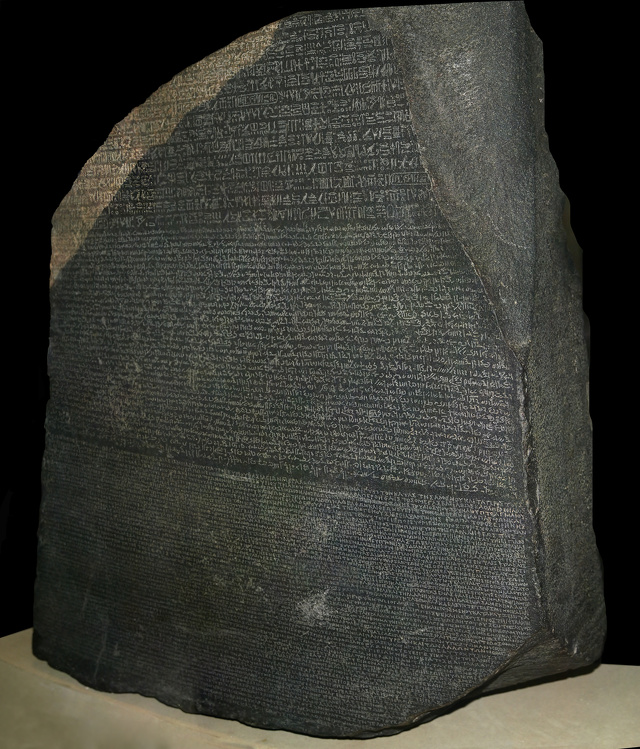

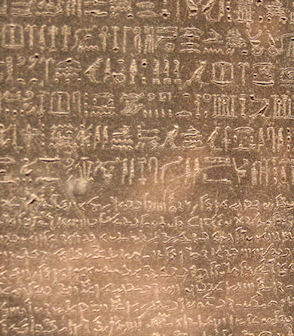

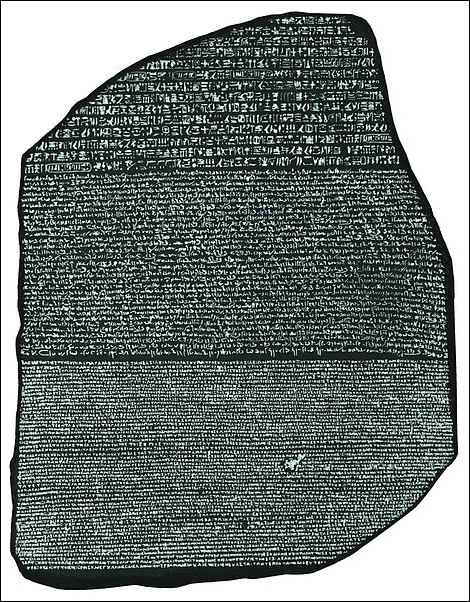

Rosetta text The Rosetta Stone is a black basalt slab 114 centimeter (45 inches) high and 74 centimeters (29 inches) wide. Inscribed in three languages: 53 lines of Greek, 32 lines of demotic (a cursive script used by the Egyptians between the seventh century B.C. and the A.D. fifth century) and 16 lines of hieroglyphics. Both the demotic script and hieroglyphics were initially indecipherable. It was written by a group of priest assembled in Memphis to mark the ascension to the throne of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes in 190 B.C. and carried a Memphis decree concerning the cult of the king.

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: The Rosetta Stone is, inarguably, one of the most famous archaeological artifacts in the world. Shortly after it was uncovered by French Napoleonic troops in Egypt in 1799, it was seized by the British and transferred to the British Museum, where it has remained prominently on display for the past 200 years. The carved gray granodiorite stela is strikingly elegant, but the stone’s significance lies more in its tripartite inscription than in its aesthetics. The juxtaposition of the three passages, identical but for each having been written in a different script — Egyptian hieroglyphics, Egyptian Demotic, and Ancient Greek — would prove to be key to solving the puzzle of deciphering ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics.

The Rosetta Stone contains a decree of Ptolemy V that stated that Egyptian priests agreed to crown Ptolemy V pharaoh in exchange for tax breaks. At the time, Egypt was governed by a dynasty of rulers descended from Ptolemy I, one of Alexander the Great's Macedonian generals. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, August 14, 2021]

The Rosetta Stone isn't complete. It is a broken part of a larger slab. But even though it's missing a big chunk of the hieroglyphs from its long-lost top section, many of the missing parts can be ascertained as the stone has the same message repeated three times in the three different kinds of writing. [Source Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, July 24, 2022]

Egyptian demotic script was used for "the contemporary language used in everyday speech as well as administrative documents," Foy Scalf, head of research archives and a research associate at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, told Live Science. In contrast, "the grammar of the hieroglyphic section imitates Middle Egyptian," the phase of the Egyptian language associated with Egypt's Middle Kingdom period, which spanned from about 2044 B.C. to 1650 B.C., he explained. "By the Ptolemaic period, Middle Egyptian was often used for very formal inscriptions, as Egyptian scribes considered it a classical version of their language whose imitation added authority to the text."

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Rosetta Stone, in Hieroglyphics and Greek: With Translations and an Explanation of the Hieroglyphical Characters, and Followed by an Appendix of Kings' Names” by Samuel Sharpe (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Writing of the Gods: The Race to Decode the Rosetta Stone” by Edward Dolnick (2022) Amazon.com;

“Cracking the Egyptian Code: The Revolutionary Life of Jean-François Champollion” by W. Andrew Robinson (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Keys of Egypt: The Race to Crack the Hieroglyph Code” by Lesley Adkins (2001) Amazon.com;

“Cracking Codes: The Rosetta Stone and Decipherment” by Richard Parkinson Amazon.com;

“The Rosetta Stone” by E. A. Wallis Budge (1904) Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt” by Kathryn A. Bard Amazon.com;

“Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt” by Steven Blake Shubert and Kathryn A. Bard (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Egyptology” by Ian Shaw and Elizabeth Bloxam (2020)

Amazon.com;

“Treasures of Egypt: A Legacy in Photographs from the Pyramids to Cleopatra” by National Geographic (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Ancient Egypt: Beyond Pharaohs”

by Douglas J. Brewer (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com; Wilkinson is a fellow of Clare College at Cambridge University;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

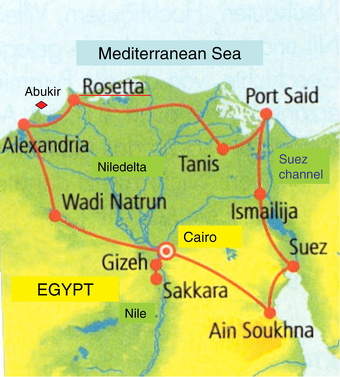

Discovery of Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone was unearthed in August 1799, a year after Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt,by French soldiers, excavating ruined Fort Rachid at the mouth of the Nile. The soldiers were part of French military expedition under a captain named Pierre Bouchard that was part of Napoleon's invasion of Egypt. The discovery took place during construction of a fort at the town of Rashīd. Rosetta is the French name for Rashid. Around the time the Rosetta Stone was found France went to war with Britain. When the French were forced out Egypt the stone fell into the hands of the British and was taken to the British Museum in 1802, were it remains today. Egypt wants the Rosetta Stone back.

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: At the time scholars had been trying to decipher hieroglyphics for hundreds of years. The significance of the stone likely would have gone unrecognized had it not been for the fact that Napoleon’s invasion included a cadre of French academics who had instructions to seize everything of cultural and historical significance. Bouchard passed the stone along to the scholars who worked on it until 1801 when the British defeated the French. With the exception of its relocation to a bunker during World War I, the stone has been in the British Museum since 1802. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, 2017]

Simon Singh of the BBC wrote: “In the summer of 1798, the antiquities of ancient Egypt came under particular scrutiny when Napoleon Bonaparte dispatched a team of historians, scientists and draughtsmen to follow in the wake of his invading army. In 1799, these French scholars encountered the single most famous slab of stone in the history of archaeology, found by a troop of French soldiers stationed at Fort Julien in the town of Rosetta in the Nile Delta. [Source: Simon Singh, BBC, February 17, 2011. After completing a PhD in particle physics, Singh worked at the BBC.|::|]

“The soldiers were demolishing an ancient wall to clear the way for an extension to the fort, but built into the wall was a stone bearing a remarkable set of inscriptions. The same piece of text had been inscribed on the stone three times, in Greek, demotic and hieroglyphics. The Rosetta Stone, as it became known, appeared to be the equivalent of a dictionary. |::|

“However, before the French could embark on any serious research, they were forced to hand the Rosetta Stone to the British, having signed a Treaty of Capitulation. In 1802, the priceless slab of rock-118cm (about 46 ½ in) high, 77cm (about 30in) wide and 30cm (about 12in) deep, and weighing three quarters of a tonne-took up residence at the British Museum, where it has remained ever since. |::| “The translation of the Greek soon revealed that the Rosetta Stone contained a decree from the general council of Egyptian priests issued in 196 B.C. Assuming that the other two scripts contained the identical text, then it might appear that the Stone could be used to crack hieroglyphs. |::|

“However, a significant hurdle remained. The Greek revealed what the hieroglyphs meant, but nobody had spoken the ancient Egyptian language for at least eight centuries, so it was impossible to establish the sound of the Egyptian words. Unless scholars knew how the Egyptian words were spoken, they could not deduce the phonetics of the hieroglyphs. |::|

Deciphering the Rosetta Stone

Hieroglyphics in their developed form were phonetic symbols not merely pictures. The first man in modern history to realize this was a German mathematician named Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680) who discovered that hieroglyphics were an early form of the Coptic language. Up until his discovery it was thought that the hieroglyphics were symbols of ideas and objects not the phonetic symbols that they really were.

The Rosetta stone was key to deciphering ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs but it took more than 20 years to translate. The Frenchmen Jean-Françious Champollion (1790-1832) is given credit with the deciphering the hieroglyphics using the Greek on the Rosetta Stone. and his knowledge of Coptic A child prodigy who delivered his first lecture on philology at the age of 16, Champollion became aware of the Rosetta Stone when he was 12 and, the story goes, he became obsessed with deciphering it. Before he reached the age of 20 he had mastered Arabic, Syriac, Hebrew, Latin and Coptic (a language related to ancient Egyptian).

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: At the time the stone was discovered, both hieroglyphics and demotic script were undeciphered, but ancient Greek was known. The fact that the same decree was preserved in three languages meant that scholars could read the Greek portion of the text and compare it with the hieroglyphic and demotic portions to determine what the equivalent parts were. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, August 14, 2021]

"The Rosetta inscription has become the icon of decipherment, in general, with the implication that having bilinguals is the single most important key to decipherment. But notice this: although copies of the Rosetta inscription were circulated among scholars ever since its discovery, it would take more than two decades before any significant progress in decipherment was made" Andréas Stauder, an Egyptology professor at École Pratique des Hautes Études in Paris, told Live Science.

Since Champollion "knew Coptic — the last stage of ancient Egyptian, written in Greek letters — he could figure out the sound value of hieroglyphs from the correspondence between the Egyptian hieroglyphs and the Greek translation on the Rosetta Stone," James Allen, a professor emeritus of Egyptology at Brown University, said. "Champollion's knowledge of Egyptian Coptic meant that he was able to see the connection between the ancient symbols he was studying and the sounds that he was already familiar with from Coptic words," said Margaret Maitland, principal curator of the Ancient Mediterranean at National Museums Scotland. Maitland pointed out that it was the Egyptian scholar Rufa'il Zakhûr who suggested to Champollion that he learn Coptic. Champollion studied Coptic with him and Yuhanna Chiftichi, an Egyptian priest based in Paris. Arab scholars had already recognized the connection between the ancient and later forms of Egyptian language [such as Coptic]," Maitland said. "Egyptian hieroglyphs could simply not have been deciphered without Coptic," Stauder said.

Thomas Young and the Decipherment of the Rosetta Stone

Thomas Young was an English physician, polymath, and one of the brightest minds of his generation. Simon Singh of the BBC wrote: “When Young heard about the Rosetta Stone, he considered it an irresistible challenge. In 1814 he went on his annual holiday to Worthing and took with him a copy of the Rosetta Stone inscriptions. Young's breakthrough came when he focused on a set of hieroglyphs surrounded by a loop, called a cartouche. He suspected that these highlighted hieroglyphs represented something of significance, possibly the name of the Pharaoh Ptolemy, who was mentioned in the Greek text. [Source: Simon Singh, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“If this were the case, it would enable Young to latch on to the phonetics of the corresponding hieroglyphs, because a pharaoh's name would be pronounced roughly the same regardless of the language. Young matched up the letters of Ptolemy with the hieroglyphs, and he managed to correlate most of the hieroglyphs with their correct phonetic values. The decipherment of the Egyptian script was underway. He repeated his strategy on another cartouche, which he suspected contained the name of the Ptolemaic queen Berenika, and identified the sound of further hieroglyphs. |::|

“Young was on the right track, but his work suddenly ground to a halt. It seems that he had been brainwashed by the established view that the script was picture writing, and he was not prepared to shatter that paradigm. He excused his own phonetic discoveries by noting that the Ptolemaic dynasty was not of Egyptian descent, and hypothesised that their foreign names would have to be spelt out phonetically because there would not be a symbol within the standard list of hieroglyphs. Young called his achievements 'the amusement of a few leisure hours.' He lost interest in hieroglyphics, and brought his work to a conclusion by summarising it in an article for the 1819 supplement to the Encyclopaedia Britannica.” |::|

Champollion was given clues by Young who theorized the hieroglyphics were phonetic and had an alphabetical base using a bilingual-Greek-hieroglyphic text on an obelisk in Philae, Egypt. He found that seven elongated ovals or cartouches spelled something phonetically — the name of Ptolemy and also found the name of Cleopatra.

Jean-François Champollion and the Decipherment of the Rosetta Stone

Jean-François Champollion was a historian and brilliant linguist. By the age of 16 he was fluent in Latin and Greek and six ancient languages, including Coptic, derived from ancient Egyptian. Because he understood Coptic he was able to translate the meanings of the ancient Egyptian words and crack the hieroglyphic code. In the 1820s, Champollion compiled a long list Egyptian symbols with their Greek equivalents and figured out that hieroglyphics were not only alphabetic but syllabic, and in some cases determinative, meaning that they depicted the meaning of the word itself. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Simon Singh of the BBC wrote: “Champollion's obsession with hieroglyphs began around 1801 when, as a ten-year-old, he saw a collection of Egyptian antiquities, decorated with bizarre inscriptions. He was told that nobody could interpret this cryptic writing, whereupon the boy promised that he would one day solve the mystery. “Champollion applied Young's technique to other cartouches, but the names, such as Alexander and Cleopatra, were still foreign, supporting the theory that phonetics was only invoked for words outside the traditional Egyptian lexicon. Then, in 1822, Champollion received some cartouches that were old enough to contain traditional Egyptian names, and yet they were still spelt out, clear evidence against the theory that spelling was only used for foreign names. [Source: Simon Singh, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

The proper names of Ptolemy, Cleopatra and Ramses gave Champollion the necessary clues to crack the ancient Egyptian written language. Using his knowledge of Coptic, Champollion went much further than Young and devised a complete system of decipherment rules and basic grammar. He realized that hieroglyphic language was alphabetic in principal but included pictorial signs representing complete words and other signs, when attached to words, represented the word’s category (e.g. "an animal name").

Champollion focused on a cartouche containing just four hieroglyphs: the first two symbols were unknown, but the repeated pair at the end signified 's-s'. This meant that the cartouche represented ('?-?-s-s'). At this point, Champollion brought to bear his vast linguistic knowledge. Although Coptic, the descendant of the ancient Egyptian language, had ceased to be a living language, it still existed in a fossilised form in the liturgy of the Christian Coptic Church. Champollion had learnt Coptic as a teenager, and was so fluent that he used it to record entries in his journal. However, he had not previously considered that Coptic might also be the language of hieroglyphs. |::|

The Rameses cartouche clearly demonstrated the fundamental principles of hieroglyphics. It showed that the scribes sometimes exploited the rebus principle, which involves breaking long words into phonetic components, and then using pictures to represent these components. For example, the word belief can be broken down into two syllables, 'bee-leaf'. Hence, instead of writing the word alphabetically, it could be represented by the image of a bee and a leaf. In the Rameses example, only the first syllable ('ra') is represented by a rebus image, a picture of the sun, while the remainder of the word is spelt more conventionally. The significance of the sun in the Rameses cartouche is enormous, because it indicates the language of the scribes. They could not have spoken English, because this would mean that the cartouche would be pronounced 'Sun-meses'. Similarly, they could not have spoken French, because then the cartouche would be pronounced 'Soleil-meses'. The cartouche only makes sense if the scribes spoke Coptic, because it would then be pronounced 'Ra-meses'. [Source: Simon Singh, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Competition to Crack the Code of the Rosetta Stone

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Almost immediately after it was discovered in 1799, the Rosetta Stone was recognized as the potential key to decoding hieroglyphics and the long-lost language of the ancient Egyptians. Although several renowned intellectuals tackled the inscription, the competition to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphics essentially became a contest between Young and Champollion. One of the difficulties facing both men was determining whether Egyptian hieroglyphics even constituted a spoken language. Did the written characters and pictures denote letters, syllables, or words, or were they solely ideographic symbols representing an idea or action like today’s “no smoking” icons or emojis. These convey concepts, but do not represent speech. [Source:Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2017]

“Fueled by their rivalry, both men made progress, especially in determining that when certain hieroglyphic symbols were grouped together within an oval enclosure, or cartouche, they represented the personal name or title of a ruler. Because the Rosetta Stone inscription records the name “Ptolemaios” so frequently, it was possible to identify the cartouche and hieroglyphic characters that spelled out the Greek pharaoh’s name in the Egyptian text on the stone. It was a stunning breakthrough: Individual hieroglyphic symbols could represent letters or sounds. But while letters could be recognized, neither man knew anything about the language itself. Champollion then began to follow a different path. He looked to Egyptian Coptic, the little-known surviving liturgical language of Egyptian Christians, as he believed it might have been related to ancient Egyptian.

In 1822, Champollion finally solved the riddle — he was able to read hieroglyphics. He had wondered if the first hieroglyph in the cartouche, the disc, might represent the sun, and then he assumed its sound value to be that of the Coptic word for sun, 'ra'. This gave him the sequence ('ra-?-s-s'). Only one pharaonic name seemed to fit. Allowing for the omission of vowels and the unknown letter, surely this was Rameses. The spell was broken. Hieroglyphs were phonetic and the underlying language was Egyptian. Champollion dashed into his brother's office where he proclaimed 'Je tiens l'affaire!' ('I've got it!') and promptly collapsed. He was bedridden for the next five days.” |::|

Legacy of Deciphering the Rosetta Stone

Champollion had discovered that while hieroglyphs were sometimes ideograms, representing an object directly — the character of a lion can actually mean “lion” — they had phonetic value as well. For example, in hieroglyphics, the lion symbol also represents the letter L, the snake the letter J, the open hand the letter D. A somewhat poignant footnote to Champollion’s work is that he never actually saw the Rosetta Stone.

“Champollion went on to show that for most of their writing, the scribes relied on using a relatively conventional phonetic alphabet. Indeed, Champollion called phonetics the 'soul' of hieroglyphics. Using his deep knowledge of Coptic, Champollion began a prolific decipherment of hieroglyphs. He identified phonetic values for the majority of hieroglyphs, and discovered that some of them represented combinations of two or even three consonants. This sometimes gave scribes the option of spelling a word using several simple hieroglyphs or with just one multi-consonantal hieroglyph. |::|

“In July 1828, Champollion embarked on his first expedition to Egypt. Thirty years earlier, Napoleon's expedition had made wild guesses as to the meaning of the hieroglyphs that adorned the temples, but now Champollion could reinterpret them correctly. His visit came just in time. Three years later, having written up the notes, drawings and translations from his Egyptian expedition, he suffered a severe stroke. He died on 4th March 1832, aged 41, having achieved his childhood dream.” The stress of the intensive work is believed to have contributed to his death. His wasn't fully appreciated until 30 years later after German scholars figured the full complexity of the hieroglyphics and gave accurate translations for texts misunderstood by Champollion. Today hieroglyphics can be read about as well as the writing for most languages.

Why the Rosetta Stone Has Three Kinds of Writing?

The Rosetta Stone is inscribed with three ancient texts — two Egyptian and one Greek. Two of the texts are different scripts for the same language. All this, begs the question why does it have three different kinds of writing in the first place?Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science: The reason stems from the legacy of one of Alexander the Great's generals. The Greek text on the stone is linked with Egypt's Ptolemaic dynasty, founded by Ptolemy I Soter, a Greek-speaking Macedonian general of Alexander’s. Alexander conquered Egypt in 332 B.C., and Ptolomy I Soter seized control of the country nine years later following Alexander's death. (Cleopatra, who died in 30 B.C., was the last active ruler of the Ptolemaic line.) The stone isn't associated with Ptolemy I Soter, but with his descendant Ptolemy V Epiphanes, whose priests had the inscribed message composed in three different scripts that each played important social roles during the Ptolemaic dynasty.[Source Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, July 24, 2022]

Ancient Greek grew to become widely used in ancient Egypt among the educated class during the Ptolemaic dynasty, and there were modern scholars who still understood it at the time of the Rosetta Stone's discovery. The use of hieroglyphics began to die out after the Romans took over Egypt in 30 B.C., with the last known Egyptian hieroglyphic writing appearing in the fourth century A.D.

The context in which the decree was inscribed sheds light on why it was written in three different scripts, Scalf said. When the priests assembled in Memphis to carve the stone, the political situation in Egypt was complicated. "Ptolemy V Epiphanes was only a small child when his father Ptolemy IV Philopator died in 204 B.C., leaving the Egyptian empire to be run by regents," Scalf said. "The transition of power came at an unfortunate time for the royal administration."

The Seleucid Empire of western Asia — founded by the Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator in 312 B.C. — took advantage of the power vacuum following Ptolemy IV Philopator's death and invaded areas on the western Mediterranean coast to undermine Ptolemaic control there, Scalf noted. Simultaneously, Egypt was dealing with a major revolt of native groups that had begun late in Ptolemy IV Philopator's reign. Given the complex politics that Ptolemy V Epiphanes faced, the assembly of the priests at Memphis for his coronation was likely rich with several layers of meaning.

"Memphis was the traditional capital of the pharaonic empire, and thus a coronation there held symbolic value for the king and his court," Scalf said. "The gathering for the coronation at Memphis likely served as an important connection with the past, an intentional symbol of the consolidated rule of Ptolemy V Epiphanes over Egypt, as well as an acquiescence to the Egyptian priesthood's desire to meet in their sacred city of Memphis rather than Alexandria (the capital of Ptolemaic Egypt)," he noted.

Champollion's table of hieroglyphic phonetic characters with their demotic and Coptic equivalents (1822)

Contents of the Rosetta Stone

The message on the Rosetta Stone was likely written by a council of priests in the Egyptian city of Memphis, an ancient capital about 25 kilometers (15.5 miles) south of Cairo. The priests carved the stone in 196 B.C., during the ninth year of the reign of Ptolemy V Epiphanes (lived from 210 B.C. to 180 B.C.), who inherited the throne at age 5 and was officially crowned at age 13. It celebrates his coronation as ruler of Egypt. [Source Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, July 24, 2022]

The inscription of the decree on stones set up throughout Egypt followed a previous pattern for official pronouncements. "Similar trilingual decrees had been promulgated before, such as those by Ptolemy IV Philopator after the battle of Raphia in 217 B.C., and by Ptolemy III Euergetes in the Canopus Decree of 238 B.C.," Scalf told Live Science. "Thus, while such a decree was not necessarily a standard matter, it followed a well-established precedent."

According to Live Science: The Rosetta Stone catalogs some of Ptolemy V Epiphanes' accomplishments, such as gifts to temples, tax cuts and the quelling of a portion of Egypt's internal revolts. In return for these services to Egypt, the priests pledged a number of actions to support Ptolemy V Epiphanes, such as constructing new statues, adding better decorations to his shrines, and holding festivals for his birthday and day of accession to the throne, Britannica noted. "The decree helped him flex his influential and propagandistic muscle by depicting him as the legitimate king who fights on behalf of the Egyptians and portraying the Egyptian priesthood as supporting him," Scalf said.

Among the most important outcomes of the decree "was establishing a number of benefits for the powerful Egyptian priesthood in exchange for their support of the young king," Scalf said. "These benefactions demonstrate the power negotiations at play between the ruling house and other invested parties such as the priesthood, who had significant influence in the public's perception of the king."

Great Revolt at the Time the Rosetta Stone was Written

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: “While many people may be familiar with the basics of the Rosetta Stone, few perhaps know what the text says or understand the events that influenced the stela’s creation. The stone was once part of a series of carved stelas that were erected in locations throughout Egypt amid events of the Great Revolt (206–186 B.C.). These monuments were inscribed with the Third Memphis Decree, which was issued by Egyptian priests in Memphis in the year 196 B.C. to celebrate Ptolemy V’s achievements and affirm the young king’s royal cult. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2017]

“It is sometimes forgotten that the Ptolemaic rulers were actually Greek. Ptolemy V (r. 205-180 B.C.) came to power as a child of six when his father, Ptolemy IV (r. 222-205 B.C.), died. Ptolemy V was no more than 14 when the decree was written. The decree, nonetheless, chronicled his victory in the Nile Delta over a faction of native Egyptians who were violently rebelling against Hellenistic rule. While specifics of the revolt [sometimes referred to as the Great Revolt] remain obscure today, the little that is known has been drawn from a few surviving texts and inscriptions, including the Rosetta Stone.

“The Great Revolt was at least a hundred years in the making, and it would alter Greco-Egyptian relations forever, archaeologist Jay Silverstein says, “The Great Revolt is a fascinating and forgotten piece of history that offers some interesting insights on Egyptian ethnicity, imperialism, and Hellenism.” Other than a brief period between 402 and 343 B.C., by the late third century B.C. Egypt had been occupied by foreign invaders for more than three hundred years. Greek (specifically Macedonian) rule over Egypt began with Alexander the Great, who conquered the territory in 332 B.C. and “liberated” Egypt from the oppressive Persian Empire. After his death in 323 B.C., Alexander’s trusted general Ptolemy I inherited the kingdom, ushering in a period of Ptolemaic dynastic rule that would last until the death of Cleopatra in 30 B.C.

“Initially, relations between the Greek Ptolemaic rulers and the Egyptian masses proceeded smoothly, if cautiously. However, as the third century B.C. progressed, Greco-Egyptian affairs deteriorated. An influx of Greek colonists to Egypt, along with worsening economic conditions, spawned resentment. A grassroots nationalistic movement also began to take hold, fueled in part by Egyptian soldiers who had served in Ptolemy IV’s army in the Battle of Raphia in 217 B.C. Having gained confidence and experience in the Ptolemaic army, many veterans returned home unwilling to accept their role as second-class citizens and actively pushed for the return of Egyptian leadership. By 206 B.C., the pot boiled over and armed rebellion against Greek rule broke out.

“While the insurrection was centered mostly in Upper Egypt around Thebes, where a new pharaoh of Egyptian lineage was installed, the turmoil also extended to the Nile Delta. Parts of the Rosetta Stone document the brutal victory of Ptolemy V’s forces over insurgents in a town to the west of Thmuis: “He went to the fortress…which had been fortified by the rebels with all kinds of work.…The rebels who were inside of it had already done much harm to Egypt and abandoned the way of the commands of the king.…The king took that fortress by storm in short time. He overcame the rebels who were within it and slaughtered them.”

What the Rosetta Stone Says

The Translation of the first half of the Greek Section of the Rosetta Stone reads: 1. In the reign of the young one who has succeeded his father in the kingship, lord of diadems, most glorious, who has established Egypt and is pious. 2. Towards the gods, triumphant over his enemies, who has restored the civilised life of men, lord of the Thirty Years Festivals [The Sed Festival, originally held at thirty-year intervals after a king’s coronation, in order to renew a king’s physical powers.], even as Hephaistos [the creator god Ptah] the Great, a king like the Sun [the sun god Ra], 3. Great king of the Upper and Lower countries [The South and North of Egypt], offspring of the Gods Philopatores, one of whom Hephaistos has approved, to whom the Sun has given victory, the living image of Zeus [name for the Egyptian god Amun], son of the Sun, Ptolemy 4. Living for ever, beloved of Ptah, in the ninth year, when Aetos son of Aetos was priest of Alexander, and the Gods Soteres, and the Gods Adelphoi, and the Gods Euergetai, and the Gods Philopatores and 5. The God Epiphanes Eucharistos; Pyrrha daughter of Philinos being Athlophoros of Berenike Euergetis; Areia daughter of Diogenes being Kanephoros of Arsinoe Philadelphos; Irene 6. Daughter of Ptolemy being Priestess of Arsinoe Philopator [Eponymous priests; priests and priestesses, always with Greek names, attached to the royal cult, who served in their office for a year and were arranged in two colleges in a completely Greek institution]; the fourth of the month of Xandikos, according to the Egyptians the 18th Mekhir. DECREE. There being assembled the Chief Priests and Prophets and those who enter the inner shrine for the robing of the

“7. Gods, and the Fan-bearers and the Sacred Scribes and all the other priests from the temples throughout the land who have come to meet the king at Memphis, for the feast of the assumption 8. By Ptolemy, the ever-living, the beloved of Ptah, the God Epiphanes Eucharistos, the kingship in which he succeeded his father, they being assembled in the temple in Memphis this day declared: 9. Whereas king Ptolemy, the ever-living, the beloved of Ptah, the god Epiphanes Eucharistos, the son of King Ptolemy and Queen Arsinoe, the Gods Philopatores, has been a benefactor both to the temples and 10. To those who dwell in them, as well as all those who are his subjects, being a god sprung from a god and goddess (like Horus the son of Isis and Osiris, who avenged his father Osiris) (and) being benevolently disposed towards

“11. The gods, has dedicated to the temples revenues in money and corn and has undertaken much outlay to bring Egypt into prosperity, and to establish the temples, 12. And has been generous with all his own means; and of the revenues and taxes levied in Egypt some he has wholly remitted and others he has lightened, in order that the people and all the others might be 13. In prosperity during his reign; and whereas he has remitted the debts to the crown being many in number which they in Egypt and in the rest of the kingdom owed; and whereas those who were

“14. In prison and those who were under accusation for a long time, he has freed of the charges against them; and whereas he has directed that the gods shall continue to enjoy the revenues of the temples and the yearly allowances given to them, both of 15. Corn and money, likewise also the revenue assigned to the gods from vine land and from gardens and the other properties which belonged to the gods in his father’s time; 16. And whereas he directed also, with regard to the priests, that they should pay no more as the tax for admission to the priesthood than what was appointed them throughout his father’s reign and until the first year of his own reign; and has relieved the members of the

“17. Priestly orders from the yearly journey to Alexandria; and whereas he has directed that impressment for the navy shall no longer be employed; and of the tax in byssus [fine linen] cloth paid by the temples to the crown he 18. Has remitted two-thirds; and whatever things were neglected in former times he has restored to their proper condition, having a care how the traditional duties shall be fittingly paid to the gods; 19. And likewise has apportioned justice to all, like Hermes (name for the Egyptian god Thoth] the great and great; and has ordained that those who return of the warrior class, and of others who were unfavourably 20. Disposed in the days of the disturbances [A reference to the years since 205 B.C., during which Upper Egypt had been ruled by two rebel native pharaohs], should, on their return be allowed to occupy their old possessions; and whereas he provided that cavalry and infantry forces and ships should be sent out against those who invaded

“21. Egypt by sea and by land, laying out great sums in money and corn in order that the temples and all those who are in the land might be in safety; and having 22. Gone to Lycopolis [A town in the ninth nome (administrative area) of the Delta, probably near Busiris but not identified with certainty] in the Busirite nome, which had been occupied and fortified against a siege with an abundant store of weapons, and all other supplies (seeing that disaffection was now of long 23. Standing among the impious men gathered into it, who had perpetrated much damage to the temples and to all the inhabitants of Egypt), and having 24. Encamped against it, he surrounded it with mounds and trenches and elaborate fortifications; when the Nile made a great rise in the eighth year (of his reign), whichusually floods the 25. Plains, he prevented it, by damming at many points the outlets of the channels (spending upon this no small amount of money), and setting cavalry and infantry to guard.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024