Home | Category: Death and Mummies

JUDGMENT PROCESS FOR THE DEAD IN ANCIENT EGYPT

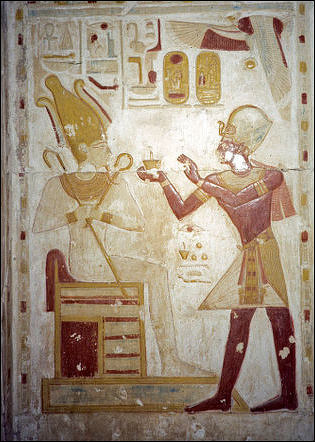

The ancient Egyptians believed that the dead could reach a kind of paradise where they could live forever but they had to be judged first for the life they had led. The ancient Egyptians thought everyone possessed ka, or life force, and ba, a soul. Upon death, the ka left the body first, wandering aimlessly. The ba remained in the body until burial. Then, the ba — guided by spells and images painted on the tomb walls and amulets attached to the body — proceeded on a journey through the underworld. The falcon-headed god Horus led the ba through doorways of fire and cobras and past demons with knives to the halls of judgment, where the deceased was tested. [Source: Ann R. Williams, October 19, 2022; Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

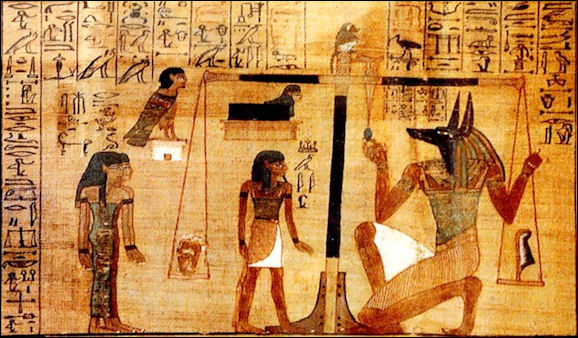

Overseen by the jackal-headed god Anubis, the heart was weighed against a feather of Maat, the goddess of truth, justice and cosmic harmony. If the person had committed a great number of harmful deed the person's heart would be heavier than the feather and the person's soul would be obliterated. On the other hand, if their deeds were generally good, they passed forward and had the opportunity to successfully navigate the underworld.

During part of this ritual — the “Negative Confession” — the deceased had to deny committing theft, murder, causing others distress, and other transgressions. Osiris, king of the underworld, and other gods presided as judges. If the deceased failed this test, a monster goddess named Ammut — part lion, part crocodile, and part hippopotamus — devoured the soul, dooming the deceased to a perpetual coma.

The heart is believed to be the center of intelligence in ancient Egyptian cosmology and plays an important role in the afterlife journey.To protect the organ, it was common for the heart to be separately embalmed and then returned to the body during mummification. If the heart balances, the ba reunites with the ka (which had been wandering aimlessly), creating a spirit called akh. The spirit emerges in the bright realm ruled by the crowned Osiris, called the Field of Reeds, a land of beautiful mountains and rivers. Here, the deceased is reunited with his loved ones, including his pets. The utopian life is now his for eternity.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN VIEWS ON DEATH AND THE AFTERLIFE africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“King Tut. the Journey Through the Underworld” by Sandro Vannini (2020) Amazon.com;

“In the Tomb of Nefertari: Conservation of the Wall Paintings” by Robert Steven Bianchi and John K. McDonald (1993) Amazon.com;

“Becoming Osiris: The Ancient Egyptian Death Experience” by Ruth Schumann Antelme and Stéphane Rossini (1998) Amazon.com;

”The Attitude of the Ancient Egyptians to Death and the Dead: The Frazer Lecture for 1935" by Alan H. Gardiner Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Ideas Of The Future Life” by E. A. Wallis Budge (1899)

Egyptian Amduat: The Book of the Hidden Chamber” by Erik Hornung (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Sungod's Journey Through the Netherworld: Reading the Ancient Egyptian Amduat” by Andreas Schweizer-Vüllers (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Egyptian Heaven and Hell: Volume I, II and III ” by E. A. Wallis Budge (1906) Amazon.com;

“Death and Burial in Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2015) Amazon.com

”Burial Customs in Ancient Egypt: Life in Death for Rich and Poor”, Illustrated,

by Wolfram Grajetzki (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Egyptian Book of the Dead (Penguin Classics) by Wallace Budge and John Romer (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day” The Complete Papyrus of Ani Featuring Integrated Text and Full-Color Images, Illustrated, by Dr. Raymond Faulkner (Translator), Ogden Goelet (Translator), Carol Andrews (Preface) (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the Egyptian Book of the Dead” by Rita Lucarelli and Martin Andreas Stadler (2023) Amazon.com;

“Osiris and the Egyptian Resurrection, (Volume 1), Illustrated, by Sir Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge (1857-1934) Amazon.com;

“Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt” by Jan Assmann (2005) Amazon.com;

“Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt” by John H Taylor (2001) Amazon.com;

Ancient Egyptian Journey to Afterlife

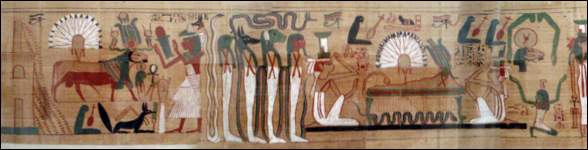

After death, the Egyptians believed the dead went on a spiritual journey, along which they encountered demons and other malevolent creatures, who tried to slow and disrupt the journey. The dead were generally unable to negotiate all the obstacles by themselves and needed the help of the gods. The falcon-headed god Horus, for example, helped lead the dead through doors of fire and cobras.

Preserving the body as mummy aided the journey in the afterlife. The dead were sometimes buried with spells to aid them in navigating the underworld. Many tombs were filled with spells and incantations from the “Book of the Dead” that were supposed to help them get past the obstacles and solicit help from guardian gods that could help them. Sometimes people were buried with manuscripts of the entire “ Book of the Dead”. A 16-meter (52-foot) -long copy of this was recently found in a tomb at Saqqara. [Source:Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

Egyptians believed that the dead could enter the afterlife in one of three ways: 1) through the underground world of the dead ruled Osiris: 2) a pharaohs rebirth in the morning; and 3) the pharaohs rise at night into the stars.

According to one text the journey to the afterlife could take several earthly lifetimes. The pharaohs undertook the journey in a boat. On Thutmose III’s journey the river dried up and the boat became a snake that moved across the sand; helpful deities helped slay his enemies whose body parts were tossed into flaming pits. The dead pharaoh was reborn when a scarab nudged the sun out of the underworld to usher in a new day.

Ancient Egyptian Views on Judgement After Death

Ancient Egyptians appear to have believed in a Judgement Day after death and that ascension to heaven was linked with moral deeds and good behavior in real life. They believed that during a judgement ceremony the heart of the dead was weighed on a scale against the feather of truth to determine the fate of its owner in the afterlife. One line from the “ Book of the Dead” goes: “Oh my heart that I have had when on earth, don’t stand up against me as a witness, don’t make me a case against me beside the great god.” The feather of truth, it is said, was an ostrich feather, a symbol of Maat, the god responsible for keeping the cosmos in order.

The heart-weighing ceremony was watched over by the gods Osiris, Maat, Thoth, Anubis and Horus. Anubis weighed the heart while Osiris and the others watched as judges. Orisis’s officers were composed of terrible demons, who guarded his gates, or who sat as assessors in his great hall of judgment. In this hall of the truths, by the side of the king of the dead, there squatted forty-two strange demonic forms, with heads of snakes or hawks, vultures or rams, each holding a knife in his hand. Before these creatures, the eater of blood, eater of shadows eye of flame, breaker of bones, breath of flame, leg of fire, and others of like names, the deceased had to appear and confess their sins. If they they could declare that they had neither stolen, nor committed adultery, nor reviled the king, nor committed any other of the forty-two sins, and if the great balance on which his heart was weighed showed that they were was innocent, then Thoth, the scribe of the gods, wrote down his acquittal. Horus then took the deceased by the hand and led the new subjects to their father Osiris.[Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Those whose heart weighed the same as the feather moved on to the Egyptian equivalent of heaven. Those whose heart weighed too little or too much disrupted the order of the universe and were condemned to the Egyptian equivalent of hell. They were snatched by a monster that was part crocodile, lion and hippopotamus and devoured and condemned to a life in a coma. Mummies were believed to sometimes lie about their sins to win passage to the afterlife.

Judgment after Death in Ancient Egypt (Negative Confession)

Martin Stadler of Würzburg University wrote: “According to Egyptian funerary beliefs, judgment after death was a process the deceased had toundergo in order to become “justified” and thus qualify for entrance into the hereafter. In this sense judgment can be considered to have been an initiation ritual. From the Middle Kingdom onward, judgment comprised a series of “posthumous” trials set in various Egyptian cities of particular mythic and cultic significance (featured in The Book of the Dead, spells 18 and 20, with precursors in the Coffin Texts and other Middle Kingdom sources). These trials, based upon the mythological judgment and subsequent justification of Osiris, constituted a model for each deceased’s justification. The most popular concept of judgment after death was expressed in BD spell 125, which supplied both the relevant text to be recited (including the “negative confession” proper) and a depiction of the judgment scene. First attestations of BD spell 125 do not predate the New Kingdom; we therefore have good reason to assume that the concept of judgment after death was not fully developed before that period. However, there are precursors in the Coffin Texts, which themselves may have precursors reaching as far back as the Old Kingdom (based on the discovery of Pyramid Texts containing spells that were previously known only from Middle Kingdom coffins). [Source: Martin Stadler, Würzburg University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“The roots of the belief in judgment after death possibly lie in the addresses to visitors found in tombs of the 4th Dynasty. Some of these texts threaten entrants who violate the ritual purity of the tomb or mortuary cult with a judgment in the hereafter before the Great God. Certain elements of the belief, such as the scale upon which the heart (or other body part) of the deceased would be weighed in judgment, are present in the Coffin Texts. The concept of judgment after death first appears fully developed, however, in Book of the Dead papyri of the New Kingdom and is depicted as such in the relevant vignettes therein. BD spell 125 has survived in numerous copies, chiefly in cursive hieroglyphs and hieratic, but a demotic version (dated to 63 CE by its colophon) is also known.

“The concept of judgment after death appears in sources other than The Book of the Dead. In The Book of Gates, for example, first attested in King Horemheb’s tomb (KV 57), the judgment hall of Osiris is featured. There the judgment process is conceptualized as being complexly linked to the solar journey through the netherworld, during which the sun god is vindicated, thus providing a model for the deceased. There are also references to a judgment after death in Egyptian wisdom texts, including The Instruction of Merikara (E 53–56) and The Demotic Wisdom Book.

“Some researchers have proposed, on the basis of Diodorus I 91–93, that a judgment of the deceased was “performed” as a drama at the tomb during the burial rites and have tried to find support in Egyptian sources for the proposition. Opponents of this hypothesis consider that Diodorus likely demythologized what he had heard about Egyptian religion and the mythic judgment after death.”

Weighing of the heart

Book of the Dead Spell 125: the Judgement Procedure

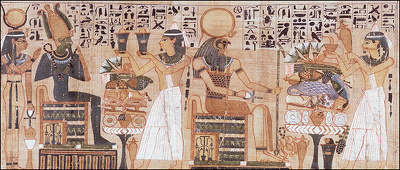

Martin Stadler of Würzburg University wrote: “The vignette of the judgment after death, attested from the mid-18th Dynasty onward, gives us an idea of the actual trial procedures. Although its association with Book of the Dead spell 125 is well known, the vignette is also found in accompaniment to other BD spells associated with the judgment. After the New Kingdom, the representation is found in a variety of contexts—coffins, shabti chests, mummy bandages, shrouds, and in one instance, a relief in the small Ptolemaic temple of Deir el-Medina. Although the set of figures displayed in the judgment scene changes over time, a typical representation comprises the introduction of the deceased to the judgment hall by a deity (Anubis, Thoth, Maat, or the Goddess of the West); a scale on which the deceased’s heart is weighed against a feather (the symbol of maat: cosmic order and justice); a devourer (a beast that is part lion, part crocodile, and part hippopotamus), who stands by, ready to eat the heart of—and thereby annihilate—the sinful deceased; Thoth, who records the result in writing; and the enthroned Osiris, presiding as chief judge. All or some of a group of 42 judges are also shown. Abbreviated versions of the vignette exist, as well as more elaborate depictions. [Source: Martin Stadler, Würzburg University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“According to its title, BD spell 125 is to be recited by the deceased when entering the judgment hall. It is intended to ensure that the individual will pass through the judgment phase and be found ethically worthy to enter the realm of Osiris. To this end, the deceased claims to know the names of the judges and asserts his purity. As the knowledge he displays reveals familiarity with cults, rituals, and cult topography, it presents him as one who is versed in religious matters. In the spell’s main section, the deceased addresses each of the 42 judges by his name and cult center. Each address is followed by the deceased’s denial of having committed a specific sin, hence the term “negative confession.” The 42 negative confessions confirm the speaker’s equanimity—that is, they confirm that his behavior did not undermine or disturb the societal peace (for example, through theft, adultery, murder, or adding to the balance) and that he acted according to the cultic prescriptions, such as that of respecting the cultic chastity. Together with Egyptian instructions that parallel BD spell 125, and autobiographical texts that commemorate the achievements of individuals of the Egyptian elite, the negative confession is a major source of ancient Egyptian ethical standards. A life lived in accordance with these standards was a life lived according to maat. Over the more than 1500 years of the spell’s tradition, the set of negative confessions remained remarkably stable, varying from (BD) manuscript to manuscript only in sequence. Variations are particularly noticeable between the redactions of the New Kingdom, Third Intermediate Period, and Late Period, where it is apparent, at least in some cases, that scribes had re- or misinterpreted words or phrases when copying.

Guide To The Afterlife — Custodian For Goddess Amun

“Some scholars have suggested that BD spell 125 is an adaptation of the oaths of purity sworn by priests during their initiations. This suggestion is prompted by the texts of two priestly oaths whose structure and content are reminiscent of the negative confession of BD 125. The oaths, however, are written in Greek on papyri of Roman date. It has been argued that the recent discovery that the oaths are in fact translations from Egyptian constitutes further support for the suggestion. The oaths’ Egyptian version is contained in the so-called Book of the Temple, a manual on the ideal Egyptian temple. However, there are no known manuscripts of The Book of the Temple that predate the Roman Period. Therefore, the text might be much younger than the first witnesses of BD spell 125, although a Middle Kingdom date for the Egyptian priestly oaths has been advocated on the basis of The Book of the Temple’s Middle Egyptian grammar. This dating method has not been unanimously accepted by Egyptologists; thus it cannot be definitely excluded that there is a reverse dependence, i.e., that the priestly oaths are, in fact, adaptations of BD spell 125. The known and available Egyptian sources do not presently allow a decisive conclusion, but it can be stated that there is a relationship between ritual texts pertaining to the temple context and texts that were used for funerary rituals, or as mortuary compositions.”

Ancient Egyptian Netherworld (Heaven) and Underworld

For those whose heart balanced on the scale, their “ba” and “ka” united to form an “ akh” , or spirit, which emerged in Osiris’s underworld. One hieroglyphic reads: “I have come forth in this daytime in my true form as a living spirit. The place of my heart’s desire is among the living in this land forever.”

judgement of the dead in the presence of Osiris

For the Egyptians, the netherworld — their version of heaven — was a pleasant place not all that different from their real world in the Nile Valley. That is why they were buried with treasures, jars of beer, knives and food — things they thought they could use in the netherworld. One Egyptologist told Smithsonian magazine: “being dead was one of the modes of existence, but a finer one. You were more perfect when you were dead.” By contrast the Romans and Greeks believed in a gloomy underworld and the Mesopotamian believed in a world like the real world but not very pleasant.

It is not so clear what the netherworld was like. The Amduat said the dead were reborn like the rising sun and lived a physical life in which one could have sex and be taken care of by servants. It also said the dead were able to communicate with the living. Other texts describe an underworld paradise and place called the Field of Reeds.

In the Book of the Dead, the Field of Reeds is depicted as a lush, plentiful version of the Egyptian way of living. There are fields, crops, oxen, people and waterways. The deceased person is shown encountering the Great Ennead, a group of gods, as well as his or her own parents. While the depiction of the Field of Reeds is pleasant and plentiful, it is also clear that manual labour is required. For this reason burials included a number of statuettes named shabti, or later ushebti. These statuettes were inscribed with a spell, also included in the Book of the Dead, requiring them to undertake any manual labour that might be the owner's duty in the afterlife. t is also clear that the dead not only went to a place where the gods lived, but that they acquired divine characteristics themselves. In many occasions, the deceased is mentioned as "The Osiris – [Name]" in the Book of the Dead. [Source Wikipedia]

Overall though the nature of the afterlife is difficult to define, because of the differing traditions within Ancient Egyptian religion. In the Book of the Dead, the dead confined to the subterranean Duat after meeting up with the god Osiris, who was . There are also spells to enable the ba or akh of the dead to join Ra as he travelled the sky in his sun-barque, and help him fight off Apep. A monster called the "Devourer of the Dead" waited in the underworld for those who had "stolen rations of bread," "pried into the affairs of others," and "had sex with a married woman."

Influence of Egyptian Afterlife Ideas on Christianity

Jo Marchant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: After Cleopatra ended her life in 30 B.C., bringing the Ptolemaic era to an end, Rome ruled Egypt. Whereas the Greeks had integrated into Egyptian culture, the Romans remade it, imposing their laws and administrative systems and, in time, their newly adopted Christian faith. At Saqqara, the last Egyptian mummies date to the third century A.D. Despite the cultural triumph of Rome, however, some Egyptian iconography lives on in Christian narratives. Many scholars have noted similarities between Egyptian and Christian religious symbolism, for example in stories of the goddess Isis and her son Horus and the Virgin Mary and her son Jesus. “A lot of the iconography in Christianity is derived from ancient Egypt,” says Ikram, of the American University in Cairo. [Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, August 2021]

Which is not to say that these images were necessarily appropriated directly; rather, in antiquity these influences ran in many directions. The historian Diarmaid MacCulloch, of Oxford, notes that Christian ideas of the afterlife in particular drew heavily on Greek belief, which by then had developed a “vocabulary” for concepts such as Plato’s notion that the human soul “might reflect a divine force beyond itself.” Plato, for his part, was influenced by Pythagoras, who is thought to have studied in Egypt in the sixth century B.C. “By the time Christians were beginning to construct their own literature,” MacCulloch writes in Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years, “their writers clearly found such talk of the individual soul and of resurrection completely natural.”

The ancient Egyptians offered a more positive view of the afterlife than the Greeks. In classic Greek literature, for example, the dead were mere shadows inhabiting a dark underworld. The Babylonian and Jewish traditions had very exclusive notions of heaven; eternal life was reserved for the gods. But Egyptian texts covering the walls inside the Saqqara pyramids describe the king’s soul rising up after death to join the sun in the sky. By around 2000 B.C., resurrection spells were written onto coffins directly, enabling even ordinary citizens such as Ta-Gemi to make the journey to idyllic, golden fields. Although the details of the afterlife changed over time, the most desirable postmortem destination during the Ptolemaic period was the “Field of Reeds,” an agricultural paradise with unfailing harvests and eternal spring. [Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, August 2021]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024