Home | Category: Death and Mummies

ANCIENT EGYPTIANS AND THE AFTERLIFE

Ramses IV mummy The Egyptians believed that life and death was a cycle that was repeated everyday with the coming and going of night and day, the passage of the seasons, the rise and fall of rulers. Reams of literature was devoted to death. "To speak the name of the dead is to make him live again." To speak the name of the dead restores the "breath of life to him who has vanished." So say the inscriptions of ancient Egypt. Those judged worthy boarded a boat to paradise while sinners died a second death, their heart eaten by a monster that is part crocodile, part lion and part hippo.

Funerary literature says that the dead “went away alive” (Pyramid Texts 213, §134a), and the Letters to the Dead confirm that the dead indeed remained active members of social systems despite the demise of their bodies. [Source: Julia Troche, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2018]

The notion of an afterlife and judgement was embraced by the ancient Egyptians millennia before it was among Christians. Attaining the afterlife was of supreme importance. During the Old Kingdom it seems that only the pharaohs were privileged enough to enjoy eternal life. Ordinary and even aristocratic Egyptians were not. Later prominent priest, bureaucrats and noblemen were welcomed into the exclusive club. Eventually anyone that could save money for a small tomb and a ritualistic funeral could achieve immortality.

"Abhorrence of death," writes scholar Daniel Boorstin, "did not lead them to fear the dead or ancestor worship. Tomb robbery could hardly have been so prevalent in all periods of the Egyptians had been haunted by fear of the dead. Excavators almost never find an unrobbed tomb. The way was to not to fear death but to deny it...Because the dead had reason to fear the living...inscribed on the walls of the chamber and the side of the sarcophagus were spells against intruders."

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN VIEWS ON JUDGEMENT, THE NETHERWORLD (HEAVEN) AND UNDERWORLD africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Becoming Osiris: The Ancient Egyptian Death Experience” by Ruth Schumann Antelme and Stéphane Rossini (1998) Amazon.com;

”The Attitude of the Ancient Egyptians to Death and the Dead: The Frazer Lecture for 1935" by Alan H. Gardiner Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Ideas Of The Future Life” by E. A. Wallis Budge (1899)

“King Tut. the Journey Through the Underworld” by Sandro Vannini (2020) Amazon.com;

Egyptian Amduat: The Book of the Hidden Chamber” by Erik Hornung (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Sungod's Journey Through the Netherworld: Reading the Ancient Egyptian Amduat” by Andreas Schweizer-Vüllers (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Egyptian Heaven and Hell: Volume I, II and III ” by E. A. Wallis Budge (1906) Amazon.com;

“Death and Burial in Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2015) Amazon.com

”Burial Customs in Ancient Egypt: Life in Death for Rich and Poor”, Illustrated,

by Wolfram Grajetzki (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Egyptian Book of the Dead (Penguin Classics) by Wallace Budge and John Romer (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day” The Complete Papyrus of Ani Featuring Integrated Text and Full-Color Images, Illustrated, by Dr. Raymond Faulkner (Translator), Ogden Goelet (Translator), Carol Andrews (Preface) (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the Egyptian Book of the Dead” by Rita Lucarelli and Martin Andreas Stadler (2023) Amazon.com;

“Osiris and the Egyptian Resurrection, (Volume 1), Illustrated, by Sir Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge (1857-1934) Amazon.com;

“Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt” by Jan Assmann (2005) Amazon.com;

“Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt” by John H Taylor (2001) Amazon.com;

Ancient Egyptian Preparations for Death

The Egyptians were obsessed with death and the afterlife, much more so than the Mesopotamians and Greeks. Death was regarded as something one must prepare for during life and take care of after death. This is why Egyptians bodies were mummified, their tombs were fill possessions for the afterlife and their prayers went out to hundreds deities, all of whom had to be placated with chants, rituals and offerings. The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus put it this way: “The Egyptians say their houses are only temporary lodgings and their graves are their real houses.”

Ann R. Williams wrote in National Geographic History: No religion can avoid the subject, but the ancient Egyptians built their faith around it. The worldly life, proclaimed the priests, was just a prelude to eternal life beyond the grave. The ancient Egyptians lived this life to the fullest, and expected to continue doing so upon death. [Source: Ann R. Williams, October 19, 2022]

But to ensure a flourishing afterlife, certain provisions were required, including a preserved body (aka a mummy), a stocked tomb, and animal companions. Even then, eternal life was not guaranteed, until the deceased found their way through the underworld, where they were tested by the god of judgment. Here are the specific steps the ancient Egyptians took to guarantee life ever after.

Egyptian View of the Spirit and the Soul

The Egyptians did not believe in single soul; they believed in a number of different entities that together comprised what Westerners think of as a soul. There is some debate among scholars as to how many components there were. Some say four. Others say six. Yet others say eight. The primary component was 1) the “ ka” , a life force that was present even in fetuses in the womb and continued to live on after a person died. This was often was often portrayed in iconography as a duplicate of its owner. When a person was living the body and the ka were united. After death it separated from the body. Another important component was 2) the “ ba” . Found in humans, animals and gods, it is a kind of cognitive soul representing self consciousness, perception and memory. It is represented in hieroglyphics by a bird with a human head, arms and hands.

Anubis Other components of the soul include: 3) the “akh” , a sort of ghostly aura or spirit represented in hieroglyphic by an ibis: and 4) the “ib “, a deep seated self that is the source of creativity and courage and is represented in hieroglyphic by a heart.

According to the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago: Ancient Egyptians believed “that an individual's personality was made up of several parts: 1) body (Xat): The mummy in the tomb, thought to house the ba after death. 2) ka (kA): Dynamic and impersonal life force. When depicted in tomb or temple scenes shown as the double of an individual, sometimes in miniature, frequently with the ka sign on the head. Rather than the ka actually having been seen as a separate double of an individual, it's likely that it was so depicted as it was inside a person and therefore looked like that person. 3) shadow/shade (Swt): An integral part of the personality which it was necessary to protect from harm. Usually represented as a black double of an individual. ba (bA): "Animation" or "manifestation," something akin to the idea of "soul." It was depicted as a human-headed bird.

5) akh Ax The "Transfigured spirit" into which the dead were transformed after the funerary rituals were completed. The akh could exert influence on the living, and the Egyptians often wrote letters to the akh of a deceased person in the belief that the malevolence of the akh was responsible for misfortune in life. 6) ) name rn The name was regarded as an essential part of an individual, as necessary for the survival of the deceased in the After-life as the ba, akh, and the preserved corpse. The name of an individual was preserved by its inclusion in funerary texts, either on papyrus or on the tomb walls. Should they wish to do so, later generations could destroy the existence and memory of a deceased individual by removing their name from their tomb.

On ba, the akh, the ka and the 'shadow' Dr Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol wrote for the BBC:“The ba was depicted as a human-headed bird, in which form the spirit could travel around and beyond the tomb, able to sit before the grave, taking its repose in the 'cool sweet breeze'. The concept of the akh was somewhat more esoteric, being the aspect of the dead in which he or she had ceased to be dead, having been transfigured into a living being: a light in contrast to the darkness of death, often associated with the stars. The notion of the ka was even more complex, being an aspect of the person created at the same time as the body, and surviving as its companion. It was the part of the deceased that was the immediate recipient of offerings, but had other functions, some of which remain obscure. The deceased, in whatever ethereal form, however, required sustenance for eternity, and it was with this basic fact in mind that the Egyptians' tombs were built.” [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Ancient Egyptian Beliefs About Death

Mourning

When a person dies, the Egyptians believed that his “ ka” , or life force, leaves his body, followed after burial by “ ba” , the soul. One passage from the “ Book of the Dead” reads: “Raise yourself. You have not died. Your life force will dwell with you forever.”

Gayle Gibson, an Egyptologist at the Royal Ontario Museum, told Smithsonian magazine: “The Egyptians didn’t want to be forgotten. They say the name of the dead is to make them live again.” [Source: Matthew Shaer, Smithsonian Magazine, December 2014]

Warsaw-based Egyptologist Wojciech Ejsmond told Business Insider Egyptians likely didn't believe that Pharaoh could rise from the dead. "Symbolically, the pharaoh is never dead," he said "But let's be honest, of course, it's symbolic. In reality, people see he's decaying." Nevertheless, Egyptians did believe that the dead could affect the living. "For example, if the body of somebody was badly treated after death, or didn't receive the proper burial or funeral rights, this person can cause accidents, or numerous bad things to members of his or her family," he said. [Source: Marianne Guenot, Business Insider, May 5, 2023]

One ancient hieroglyphic text reads: “Man perishes; his corpse turns to dust; all his relatives pass away. But writings make him remembered in the mouth of the reader. A book is more effective than a well-built house or a tomb-chapel in the west, better than an established villa or a stela in the temple!” [Source: Toby Wilkinson, an Egyptologist at the University of Cambridge. For the book, called “Writings From Ancient Egypt“, Nathaniel Scharping, Discover, September 22, 2016]

Mark Smith of the University of Oxford wrote: “We have seen that the Egyptian conception of the individual, although essentially monistic, nevertheless comprised two elements: a corporeal self and a social self. Death destroyed the integrity of both, and in order for the deceased to return to full life, both had to be reconstituted. It was not sufficient for a dead person to recover the use of his mental and physical faculties; he had to undergo a process of social reintegration as well, being accepted among the hierarchy of gods and blessed spirits in the afterlife. With corporeal and social “connectivity” thus restored, he acquired a new Osirian form. In this form the deceased enjoyed not only the benefits of bodily rejuvenation, but also the fruits of a relationship with a specific deity that simultaneously situated him within a group. [Source: Mark Smith, University of Oxford, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

Ba

Ba bird

Jíří Janák of Charles University, Prague wrote: “The ba was often written with the sign of a saddle-billed stork or a human-headed falcon and translated into modern languages as the “soul.” It counts among key Egyptian religious terms and concepts, since it described one of the individual components or manifestations in the ancient Egyptian view of both human and divine beings. The notion of the ba itself encompassed many different aspects, spanning from the manifestation of divine powers to the impression that one makes on the world. The complexity of this term also reveals important aspects of the nature of and changes within ancient Egyptian religion. [Source: Jíří Janák, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Similarly to the ka , the body, the shadow, the heart, and the name, the ba belongs to the terms and notions that describe individual components or manifestations of the ancient Egyptian concept of a person. Unlike the other terms, the ba has almost solely been interpreted as the Egyptian concept of the “soul.” The roots of this partly legitimate but still inaccurate and misleading view date back to Late Antiquity when the Greek expression psyche began to be used to describe or translate the Egyptian word ba. The translation is inaccurate because the ba could assume some physical aspects too.

“The nature of the ba of a non-royal deceased person can be illustrated well with the New Kingdom Book of the Dead spells 61, 85, and 89-92 where the ba is described as changing shapes, moving freely, and leaving the corpse during the day while reuniting with it every night. This notion of the ba has been interpreted as a personification (or manifestation) of vital powers, as a “free soul” that was part of the physical self , or as a “movement-soul” or an “activity-soul”. Although the ba was believed to be able to leave the corpse freely (to parta ke in offerings or to seek refreshment), the permanent bond between the ba and the (dead) body was one of the key elements in Egyptian notions of afterlife existence.

“The aforementioned relation between the ba and t he body was based on the symbolism of the daily solar cycle and found its cosmological reflection in the union of the sun-god’s ba with his corpse in the underworld. Although the idea of a bond between the ba and the corpse/body was present already in the Pyramid Texts (§§752, 1300-1301, 2010-2011) and the Coffin Texts (II, 67-72; VI, 69, 82-83), New Kingdom mortuary texts (e.g., Coffin Texts 335 and Book of the Dead chapter 17) explicitly present this event as a union of Ra (as the Ba ) and Osiris (as the C orpse). This idea reflects the Egyptian concept of universal renewal and resurrection, as well as the notion of a mutual relationship between the ba and the (dead) body.

“The term ba itself is attested for the entire duration of Egyptian Pharaonic civilization. The word was written variously with signs representing a saddle-billed stork and a human-headed falcon. A sign in the shape of a ram — which was linked to the ba probably for onomatopoeic reasons —was also used. Exceptionally, the ba appears also in the form of a leopard’s head, as in Pyramid Texts §1027b. The latter connection, however, has not been explained satisfactorily yet.”

Evolution of Ba

Ba in a tomb painting

Jíří Janák of Charles University, Prague wrote: “As far as we can deduce from Egyptian textual sources, the notion of the ba encompassed several interdependent aspects spanning from the notion of divinity or the manifestation of gods to super-human manifestations of the dead and the late notion of the psyche ; but it also covered other meanings like personal reputation, authority, and the S impression that one makes on the world. [Source: Jíří Janák, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The aforementioned stork-sign represents the earliest attested image related to the religious concept of the ba . It stresses the notions of impressiveness, might, and (heavenly) power, originally associated with the saddle-billed stork species in Egypt. These notions remain ed among the most prominent characteristics of the ba , even in periods when other hieroglyphs were used to denote it.

“Early Sources and the Old Kingdom In the Archaic Period and the Old Kingdom sources, the ba is mentioned almost solely in direct relation to divine beings and the king. Nevertheless, the Egyptians used the term in many, varying contexts: the ba could be ascribed to deities and kings directly, be part of names of non-royal or royal persons, or even the names of gods, royal ships, monuments, or cult places (incl. pyramids and royal domains). In these cases, it most probably represented the earthly, visible, or pondera ble manifestation of the divine, or of the powers that this divine force embodied and represented.

“In the Pyramid Texts, the terms ba or bau denoted awesome manifestations or impressiveness of the gods and of the resurrected king, or was even used to describe the gods and the king as divine powers. As the deceased king was believed to be transfigured into a super-human or rather divine entity endowed with great power and might, some Pyramid Texts spells describe him and the gods equally both as a ba and as a sekhem , i.e., a ruling or dominating power. There are spells that refer to the ba in a direct connect ion to transfiguration or resurrection, while other spells put stress on the aspect of might, impressiveness, or awe present in the ba concept.

“The (divine or royal) ba represented an awesome manifestation of a great power that was supposed to be encountered with awe and venerated by beings of lesser status. Not only did the term refer to the divine being itself, but it was in the ba (or as the ba ) that the hidden, super-natural, or divine beings could manifest their might, take actions, or make impressions . Thus, any god, natural phenomenon, or sacred object could manifest themselves as or through their ba or bau . However, unlike the term ba , which seems to have been ascribed to living beings only, the notion of bau was associated with seemingly inanimate objects as well.

“Natural phenomena or heavenly bodies (stars, constellations, the sun, and the moon) might have been viewed as ba (u ) of individual deities (e.g., the wind as the ba of Shu, Orion as the ba of Osiris) already in the Pyramid Texts and the Coffin Texts. Howeve r, the notion of earthly manifestations of divine powers developed over time. Later attestations of the word, dated to a time span from the New Kingdom to the Roman Period, thus include many references to gods and sacred animals that were believed to repre sent manifestations (of power or will) of other gods: e.g., Thoth as the ba of Ra, Sokar as the ba of Osiris, Apis as the ba of Ptah. This concept of divine manifestations and substantial relations between gods was also presented in the last section of the so-called Book of the Heavenly Cow.”

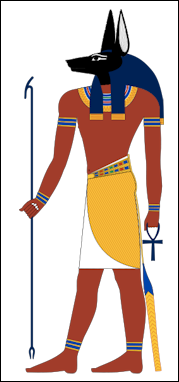

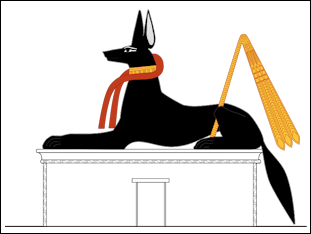

Anubis and Other Gods Associated with the Dead

Anubis Anubis was the jackal-headed god of the dead, and mummification. Even though jackals were dreaded because they dug up the graves of the dead, Anubis was watchful-guardian deity who watched over the dead. See Funerals, Judgement.

Maate is the winged Goddess of Justice. She is often represented with her wings spread on lintels over doorways in the tombs of pharaohs and their wives in the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens.

Isis, Nephthys, Neith and Selket were the four female benefactors of the dead. The four sons of Horus — Imsety, Hapy, Qebhsenuef and Duamutef — guarded the shrines of internal organs among other duties.

The goddess Selket, who guarded the shrines of internal organs, was so powerful she could cure the sting of the scorpion. She is often depicted with a scorpion on her head. The artisan-god Khnum is credited with creating human beings on his potter's wheel. Kheperi was the God of the Rising Sun and Resurrection. Montu was the God of War.

Osiris, the Dead and the Afterlife

Mark Smith of the University of Oxford wrote: For the Egyptians, the god Osiris provided a model whereby the effects of the rupture caused by death could be totally reversed, since that deity underwent a twofold process of resurrection. Mummification reconstituted his “corporeal” self and justification against Seth his “social” self, re- integrating him and restoring his status among the gods. Through the mummification rites, which incorporated an assessment of the deceased’s character, the Egyptians hoped to be revived and justified like Osiris. These rites endowed them with their own personal Osirian aspect or form, which was a mark of their status as a member of the god’s entourage in the underworld. Thus the deceased underwent a twofold resurrection as well. Not only were their limbs reconstituted, and mental and physical faculties restored, but they entered into a personal relationship with Osiris that simultaneously situated them within a group. [Source: Mark Smith, University of Oxford, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“To understand why the life, death, and resurrection of Osiris were so significant, one must first grasp how the ancient Egyptians conceived of the human being. Their conception was essentially a monistic one. They did not divide the person into a corruptible body and immortal soul. They did, however, perceive each individual as having a “corporeal self” and a “social self”. For both, “connectivity” was an essential prerequisite. Just as the disparate limbs of the human body could only function effectively as parts of a properly constituted whole, so too could the individual person only function as a member of a properly structured society. Death brought about a twofold rupture, severing the links between the constituent parts of the body while at the same time isolating the deceased from the company of his or her former associates. In effect, it was a form of dismemberment, both corporeal and social.

See Separate Article: OSIRIS (GOD OF THE DEAD AND THE AFTERLIFE): MYTHS, CULTS, RITUALS africame.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Egyptian Journey to Afterlife and Judgment

After death, the Egyptians believed the dead went on a spiritual journey, along which they encountered demons and other malevolent creatures, who tried to slow and disrupt the journey. The dead were generally unable to negotiate all the obstacles by themselves and needed the help of the gods. The falcon-headed god Horus, for example, helped lead the dead through doors of fire and cobras.

Many tombs were filled with spells and incantations from the “Book of the Dead” that were supposed to help them get past the obstacles and solicit help from guardian gods that could help them. Sometimes people were buried with manuscripts of the entire “ Book of the Dead”.

The Egyptians believed on the judgement day the heart of the dead was weighed on a scale against the feather of truth to determine the fate of its owner in the afterlife. One line from the “ Book of the Dead” goes: “Oh my heart that I have had when on earth, don’t stand up against me as a witness, don’t make me a case against me beside the great god.” The feather of truth is ostrich feather, a symbol of Maat, the god responsible for keeping the cosmos in order.

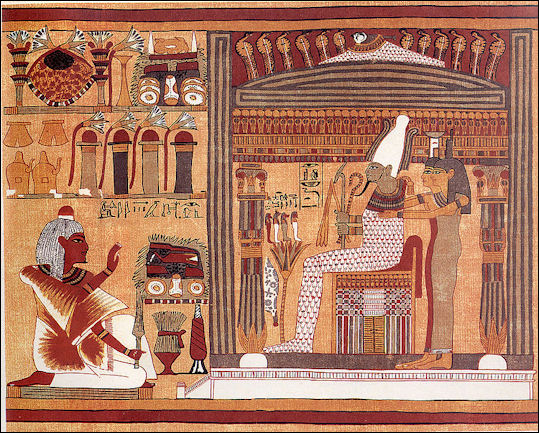

The heart-weighing ceremony was believed to be watched over by the gods Osiris, Maat (truth), Thoth, Anubis and Horus. Anubis weighed the heart while Osiris and the others watched as judges. Those whose heart weighed the same as the feather moved on to the Egyptian equivalent of heaven. Mummies were believed to sometimes lie about their sins to win passage to the afterlife.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN VIEWS ON JUDGEMENT AND UNDERWORLD africame.factsanddetails.com

Democratization of Heaven in Ancient Egypt

Lee Huddleston of the University of North Texas wrote in Ancient Near East Page: “The phenomenon called the Democratization of Heaven took place during an Egyptian Dark Age called the First Intermediate Period, ca.2400-2200 B.C.. Previously, Pharaoh, because he was the incarnation of Horus, had a right to ascend to Heaven at death. His soul returned to Osiris, but retained its Earthly identity as well. Other Egyptians could acquire Heaven only at the invitation of Pharaoh, whom they would serve in death as they had in life. Some local theologies had their own "heavens," but only after the Democratization were they all joined into the "national" heaven. [Source: Lee Huddleston, Ancient Near East Page, January, 2001, Internet Archive, from UNT \=/]

“By 2200 B.C., a refined understanding of the dynamics of salvation allowed all Egyptians an independent right to Heaven. Horus was continually reincarnated in each new Pharaoh. In turn, Horus extended his Soul to each Egyptian. Each Egyptian possessed not only his Horus-given Soul, but also a second Soul which contained his/her individuality. If the proper mortuary rituals were performed at death, the person's identity-soul was carried by his or her Horus-given Soul to a union with Osiris, where the dead merged with and became Osiris. At the end of time, when Atum resorbs all his creations into himself, only Atum, Osiris, and Horus will retain their identities. But, the souls of all Egyptians who followed the proper death rituals and joined Osiris, will retain their identities as a part of Osiris and remain forever One with God. \=/

“This complex salvationist theology only worked in Egypt because it was tied inextricably to the life cycle of the Nile [Osiris]. Annually and predictably as his wife, Isis, in her celestial form as Sirius, hovered over him, Osiris rose from death and fertilized Isis, in her aspect as the flood-plain made rich and black by his floodwaters. Their son, Horus, grew abund-antly from their co-mingling. He was the life in the land, the Spirit incarnated in the person of Pharaoh. Though Horus wore many bodies in his aspect as God-King of Egypt, he remained the Horus. His human heirodules [Pharaohs] merged with him, but retained their autonomous divinity, and through him ascended to Osiris. This dynamic made possible a perception of Salvation as the transition from the Physical Realm to the Spiritual Realm.” \=/

Ani before Osiris

Did the Democratization of the Afterlife Really Occur?

After giving considerable thought and study to the issue, Mark Smith of the University of Oxford wrote: “The so-called democratization or demotization of the afterlife in the First Intermediate Period is one of the most frequently cited instances of religious change in ancient Egypt. ... The evidence for this alleged development raises several general points.... First, it has underlined the importance of assembling all the relevant evidence before one attempts to determine the nature of a particular change in religious belief or practice. If only a part of the evidence (in this instance, only the Pyramid and Coffin Texts themselves) is taken into consideration, one can easily go astray and arrive at the wrong conclusion. [Source: Mark Smith, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Second, it has highlighted the fact that religious change is not necessarily linked to political change. Some writers present a schematic view of Egyptian history in which each successive political phase brings with it a new and distinctive religious ethos. This is overly simplistic. As Shaw points out, cultural and social patterns and trends do not always fit neatly within the framework of dynasties, kingdoms, and intermediate periods that Egyptologists are accustomed to use in studying political history. Sometimes they transcend, or even conflict with, that framework. The student of developments in the sphere of Egyptian religion must be prepared to trace them across such artificial boundaries as and when the evidence dictates.

“Third, the examination has shown that one should exercise caution in drawing sharp distinctions between royal and non-royal privileges, particularly where beliefs and practices pertaining to the afterlife are concerned. In life, the status of the king was very different from that of his subjects. But in the hereafter, his uniqueness was eroded to some extent, not least because he was now only one of an ever-increasing number of former monarchs. There is no compelling reason to assume that a king’s expectations with regard to the next world would have differed greatly from those of an ordinary person, or that the rites performed to ensure his posthumous well-being would have taken a form radically different from theirs. Nor is there any basis for the widespread assumption that any innovations in this area must have had their origin in the royal sphere prior to being adopted by non-royal individuals. With some changes, the reverse may have been true. In this respect, the fact that the earliest attested glorification rites are those performed for the non-royal deceased may be significant.

“Fourth, it has demonstrated how essential accurate dating of the relevant evidence is for a proper understanding of religious change. Uncertainties about dating not only prevent us from determining precisely when a given change occurred, but hinder our attempts to establish why and in what circumstances it happened as well. It is evident, for instance, that those who date the Coffin Texts in the form we have them now to the Middle Kingdom will arrive at a very different set of answers to such questions than those who assign their origin to the First Intermediate Period.

“Fifth, the examination has shown that religious change can only rarely be studied in isolation or on the basis of a single type of evidence. Attempts to establish the date of the first appearance of the Coffin Texts, for example, are heavily dependent on stylistic and typological analysis of the objects on which they are inscribed, as well as the contents of the spells themselves. Similarly, questions like when non-royal individuals first began to be designated as the Osiris of so- and-so, or when the canonical offering list came into being, cannot be answered without intensive study of the development of private tombs during the Old Kingdom, including analysis of their architecture, decoration, and other features, since in the absence of any more conclusive evidence, we must rely onthese to assign dates to the monuments in which the phenomena under investigation first occur.

“Sixth, it has signaled the need for us to be aware of the possibility that a change or development in the religious sphere might be masked by apparent continuity. Egyptian texts, rituals, and religious conceptions could acquire new meanings or layers of meaning over time, without necessarily losing their original ones, and the evidence for this process is sometimes subtle and difficult to detect. At the same time, one should not posit change without firm proof that it actually occurred, or assume differences when the evidence for these is lacking.

“Finally, the examination has revealed the limits of our understanding, what we can and cannot know on the basis of the evidence presently available. One seeks to understand religious change in ancient Egypt by asking and attempting to answer a series of essential questions: what is the nature of a particular change, when and where did it come about, through what agency, for what purpose, which part(s) of Egyptian society did it affect, and how lasting were its consequences. So far as the specific change examined here is concerned, there is scarcely one of these questions for which we can provide a definitive answer. In most cases, the best that we can do is narrow the choice down to two or three plausible alternatives. But by eliminating the rest, showing that they are implausible or even impossible, progress is still achieved. When one is dealing with evidence of such an equivocal nature, this in itself can be a considerable accomplishment.”

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Democratization of the Afterlife Really Occur?” by Mark Smith escholarship.org

Ancestor Worship in Ancient Egypt

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “Private religious practices could also focus on royal or non-royal ancestors who after death were sometimes elevated to the status of local or national “saints.” At Deir el-Medina, Amenhotep I and Ahmose-Nefertari were favored, venerated in local shrines, petitioned for oracles, and celebrated during festivals. Dedicatory formulae to these deities also appear on the frames of wall recesses within houses. Local ancestor worship is also attested from much earlier periods. In the Twelfth Dynasty, for example, a small shrine was built at Elephantine to support the cult of the Sixth Dynasty official Heqaib; patrons of the cult included local elite and later generations of kings. Other deified officials included Imhotep of the Third Dynasty, and the Eighteenth Dynasty official Amenhotep Son of Hapu, whose cults grew to particular prominence in the Late, Ptolemaic, and Roman Periods. It is unclear how far such cults spread into the domestic realm. Heqaib’s shrine at Elephantine, however, shows how small settlement-shrines could be closely integrated with neighboring houses, so that the religious concerns and practices within the home may often have crossed over into neighborhood shrines, and vice versa. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Ancestor worship was not restricted to deceased public figures. During at least the New Kingdom, if not earlier, deceased private individuals were also venerated in the home. Their presence can be placed within a problem-solving framework, but with the added aspects that the living wished to remember them and maintain their mortuary cult. The largest collection of evidence for private ancestor cults comes from Deir el- Medina, mainly in the form of anthropoid- bust statues, and stelae showing a deceased individual usually seated or kneeling before a table of offerings, often clutching a lotus flower. The stelae are often inscribed with offering formulae for the kA (ka) of the Ax jor n Ra: the “life force” of the “excellent, or able, spirit of Ra”—that is, the deceased at one with the gods of the afterlife and in possession of the power to intervene in the affairs of the living. The bust statues seem to have been equated with the Ax jor of the stelae, while Ax jor n Ra-formulae also appear on offering tables and basins. These items all seem to have been complementary components of a cult within the home that saw the presentation of food offerings and libations; ritual meals were possibly also shared with these objects. The cult extended to tombs, and probably shrines, where some bust statues may have been dedicated and set up to receive offerings. Similar materials have been found at sites throughout Egypt and Egyptian-occupied territory in Nubia. These must also relate to ancestor worship, but it remains uncertain how closely they corresponded in use and meaning to the materials from Deir el-Medina.”

Ancestor busts (also known as anthropoid busts) date to the New Kingdom. The majority of extant examples are from Deir el-Medina. They are most commonly interpreted as belonging to the cult of the recently deceased — that is, the ancestor cult. There are 150 extant examples of so-called ancestor busts. Friedman has argued that the busts constituted the focal point of the ancestor cult rites, thereby continuing the tradition, documented since the Old Kingdom, of the living presenting offerings to the recently deceased. According to this interpretation, the busts represented or embodied the “Ax-jqr”, the “excellent spirits,” to whom the “Ax-jqr n Ra”-stelae were also dedicated.[Source:Karen Exell, The Manchester Museum, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

Letters to the Dead in Ancient Egypt

Letters to the Dead is the conventional, modern name for a collection of texts that petition the recently deceased, typically for assistance with problems of inheritance, illness, or fertility. They are known from the Old Kingdom through the Late Period and have been preserved upon ceramic vessels and figurines, stone stelae, papyrus, and linen. The Letters were written by male and female petitioners and are addressed to both male and female dead. Though only a few dozen Letters to the Dead have been identified, they are important artifacts for better understanding interactions between the living and the dead in ancient Egypt. Notably, they illuminate the quotidian, social networks that existed between the living and the dead, help us to understand how the ancient Egyptians conceived of and interacted with the dead, and expand upon our knowledge of mortuary culture and popular religious practices in ancient Egypt.[Source: Julia Troche, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2018]

The ancient Egyptian believed that various problems often had supernatural causes. In one letter to the dead on the Cairo Bowl a woman named Dedi writes to the deceased priest Intef on behalf of his afflicted maidservant Imau; the letter petitions Intef to protect Imau and “rescue her” from the supernatural entities that could be acting against her, causing her illness)

Letters were also written to address problems that were not necessarily caused by supernatural forces, but involved supernatural actors. Letters that fall into this second category may petition the dead, not because there was no earthly recourse for the petitioner, but because the deceased was believed to be particularly powerful and influential in the matter at hand. For example, in the letters written upon the Qau Bowl, Shepsi petitions his deceased father and mother because his inheritance (land) is being robbed. Shepsi presumably has additional means of addressing his problem, such as going to court, but he calls upon his parents as the benefactors of his inheritance. He explains that it is their duty to support him in the hereafter because he continues their mortuary rites, implying a sort of social contract exists between them. He even subtly threatens his mother by explaining that if the problematic situation persists, then “who will pour out water for you?”

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Letters to the Dead” by Julia Troche escholarship.org

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024