Home | Category: Late Dynasties, Persians, Nubians, Ptolemies, Cleopatra, Greeks and Romans

PTOLEMIES (330-30 B.C.)

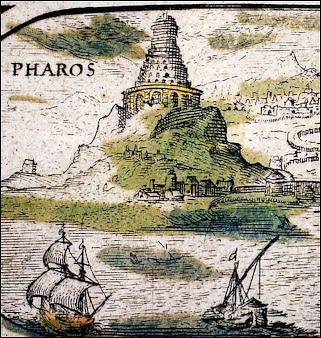

Pharos Lighthouse, one of the Seven Wonders of the World, was created under the Ptolemies in Alexandria

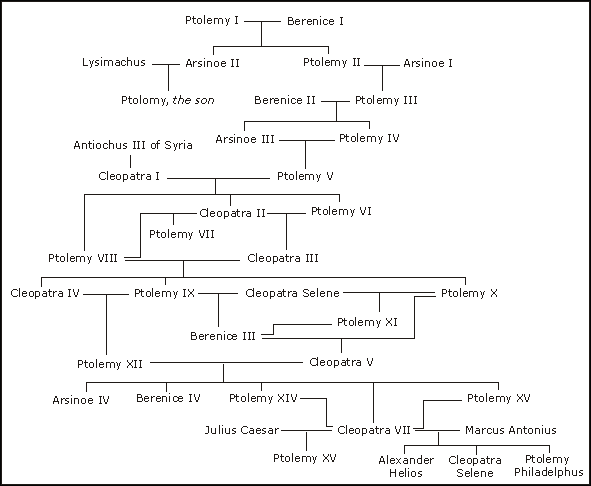

The Greco-Roman Period in Egypt (332 B.C. to A.D. 395) began when the Persians were defeated by Alexander the Great in the early fourth century B.C. When Alexander died his kingdom was divided. One of generals, Ptolemy Soter (Ptolemy I) took over Egypt. His descendants ruled Egypt until the death of Cleopatra (Cleopatra VII), who died by suicide in 30 B.C. after the defeat of her forces by Octavian, who would later be named the Roman emperor Augustus, at the Battle of Actium. After her death, Egypt was incorporated into the Roman Empire. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

Ptolemy I was a Macedonian. His successors were the the royal family of Egypt. The Macedonian-Greek dynasty (the Ptolemies) he founded ruled Egypt for more than 300 years. There were 15 Ptolemic leaders and they ruled from 332 B.C. to 30 B.C. from Alexandria.

Chip Brown wrote in National Geographic, “The Ptolemies of Macedonia are one of history's most flamboyant dynasties, famous not only for wealth and wisdom but also for bloody rivalries and the sort of "family values" that modern-day exponents of the phrase would surely disavow, seeing as they included incest and fratricide. [Source: Chip Brown, National Geographic, July 2011]

"The Ptolemies came to power after the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great, who in a caffeinated burst of activity beginning in 332 B.C. swept through Lower Egypt, displaced the hated Persian occupiers, and was hailed by the Egyptians as a divine liberator. He was recognized as pharaoh in the capital, Memphis. Along a strip of land between the Mediterranean and Lake Mareotis he laid out a blueprint for Alexandria, which would serve as Egypt's capital for nearly a thousand years.

"The Ptolemies' talent for intrigue was exceeded only by their flair for pageantry. If descriptions of the first dynastic festival of the Ptolemies around 280 B.C. are accurate, the party would cost millions of dollars today. The parade was a phantasmagoria of music, incense, blizzards of doves, camels laden with cinnamon, elephants in golden slippers, bulls with gilded horns. Among the floats was a 15-foot Dionysus pouring a libation from a golden goblet."

See Separate Articles: PTOLEMIES AND GREEK RULE OF EGYPT (330-30 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com

Website: House of Ptolemy houseofptolemy.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Last Dynasty: Ancient Egypt from Alexander the Great to Cleopatra” by Toby Wilkinson (2024) Amazon.com;

“Ptolemy I: King and Pharaoh of Egypt,” Illustrated, by Ian Worthington (2016) Amazon.com;

“When the Greeks Ruled Egypt: From Alexander the Great to Cleopatra”

by Roberta Casagrande-Kim (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Last Pharaohs: Egypt Under the Ptolemies, 305–30 BC” by J. G. Manning (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Fall of Egypt and the Rise of Rome: A History of the Ptolemies” by Guy de la Bedoyere (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Ptolemies Volume 1: Rise of a Dynasty: Ptolemaic Egypt 330–246 BC” by John D Grainger(2022) Amazon.com;

“Portraits of the Ptolemies: Greek Kings as Egyptian Pharaohs” by Paul Edmund Stanwick (Author Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra: A Life” by Stacy Schiff (2010) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra” by Diane Stanley (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Cleopatras: Discover the Powerful Story of the Seven Queens of Ancient Egypt!” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (2024) Amazon.com;

“Alexandria: The City that Changed the World” by Islam Issa (2023) Amazon.com;

“Egypt Under the Saïtes, Persians, and Ptolemies” (Classic Reprint) by E. A. Wallis Budge Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greco-Roman and Late Antique Egypt” by Katelijn Vandorpe (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization” by Barry Kemp (1989, 2018) Amazon.com;

Rulers from the Greek and Ptolemaic Periods: After Alexander the Great

Macedonian Period (332–304 B.C.)

Alexander the Great (332–323 B.C.)

Philip Arrhidaeus (323–316 B.C.)

Alexander IV (316–304 B.C.)

[Source (Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002]

Ptolemaic Period ( 304–30 B.C.)

Ptolemy I Soter I (304–284 B.C.)

Ptolemy II Philadelphos (285–246 B.C.

Arsinoe II (278–270 B.C.)

Ptolemy III Euergetes I (246–221 B.C.)

Berenike II (246–221 B.C.)

Ptolemy IV Philopator (222–205 B.C.)

Ptolemy V Epiphanes (205–180 B.C.)

Harwennefer (205–199 B.C.)

Ankhwennefer (199–186 B.C.)

Cleopatra I (194–176 B.C.)

Ptolemy VI Philometor (180–145 B.C.)

Cleopatra II (175–115 B.C.)

Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II (170–116 B.C.)

Harsiese ((ca. 130 B.C.)

Ptolemy VII Neos Philopator (145–144 B.C.)

Cleopatra III (142–101 B.C.)

Ptolemy IX Soter II (116–80 B.C.)

Ptolemy X Alexander I (107–88 B.C.)

Ptolemy XI Alexander II (80–80 B.C.)

Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos (80–51 B.C.)

Cleopatra IV Berenike III ((ca. 79 B.C.)

Berenike IV (58–55 B.C.)

Ptolemy XIII (51–47 B.C.)

Cleopatra VII (51–30 B.C.)

Ptolemy XIV (47–44 B.C.)

Ptolemy XV (44–30 B.C.)

Roman Period (30 B.C.–364 A.D.)

Augustus (30–14 B.C.)

Byzantine Period

364–476 A.D.

Early Ptolemies

Cleomenes of Naucratis: Appointed by Alexander the Great in the spring of 331 B.C., originally as Alexander's collector of revenues in the satrap of Egypt. Not a Ptolemaic ruler, Cleomenes was the antecedent of the House of Ptolemy and leader of Egypt by default after Alexander’s death in 323 B.C. [Source: House of Ptolemy, “Ptolemaic Chronology” by Alan Edouard Samuel.]

Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I (also known as Ptolemy, Son of Lagos; Ptolemy Soter)

in the Satrap of Egypt

under Philip Arrhideus: 323 - 317 B.C.

with Cleomenes as assistant (hyparchos): 323 B.C.

under Alexander IV: 317 - 311 B.C.

given epithet Soter

Wife: Eurydice

305 B.C. November 7 Soter takes title of king, Ptolemy I (Soter I)

Elevation and joint rule with Philadelphos:

Wives: Eurydice B.C., Berenice I

284 B.C., January beginning of joint regency of Soter and Philadelphus

282 B.C., between January 7 and summer death of Soter

Ptolemy II (Philadelphus)

Wives: Arsinoe I B.C., Arsinoe II

246 B.C., January 29 death of Philadelphus B.C., accession of Euergetes I

Ptolemy III (Euergetes I)

Wife: Berenice II

222 B.C., between October 18 and December 31 death of Euergetes I B.C., accession of Philopator I

Ptolemy IV (Philopator I)

210 B.C., 9 October Birth of Ptolemy V Epiphanes

210 B.C., November 30 Elevation of Epiphanes as coregent with his father Philometor

205 B.C., after October18 B.C., possibly November 28 death of Philopator

204 B.C., between summer and September 8 accession of Epiphanes

Ptolemy V (Epiphanes)

Wife: Cleopatra I

197 B.C., November 26 Anakleiteria of Epiphanes

196 B.C., March 27 Rosetta Stone inscribed

180 B.C., between February 20 and October 6 death of Epiphanes and accession of Philometor

Middle Ptolemies

Ptolemy VI Philometor

Ptolemy VI (Philometor)

regency under Cleopatra I: 180-176 B.C.

1st Sole reign: 176 - 170 B.C.

Joint reign with Ptolemy VIII 169-164 B.C.

Invasion of Antiochus IV of Syria: 169 & 168 B.C.

2nd Sole reign with Cleopatra II: 164/3-145 B.C.

Wife: Cleopatra II

176 B.C., between April 8 and October 14 death of Cleopatra I B.C., Philometor ruling B.C., married to his sister

170 B.C., October 5 beginning of joint regency of Philometor B.C., Euergetes II B.C., and Cleopatra II

164 B.C., October expulsion of Philometor

163 B.C., before May 29 return of Philometor

145 B.C., spring association of Neos Philopator on the throne

145 B.C., before September 19 death of Philometor B.C., accession of Euergetes II

Ptolemy VII (Neos Philopator)

associated ruler with his father Philometor: 145/144

regent under his uncle Euergetes II and mother Cleopatra II (who married): 14 B.C.

Ptolemy VIII (Euergetes II) "Physkon" restored

King of Cyrenaica B.C., Libya 163-145 B.C.

145 - 116

Wives: Cleopatra II B.C., Cleopatra III

131-130 revolution of Cleopatra II

116 B.C., June 28 death of Euergetes II

116 B.C., after October 29 116 B.C., death of Cleopatra II

Cleopatra III and

Ptolemy IX (Soter II) "Lathyrus"

Ruler in Cyrenaica B.C., Libya: 115 - 104/1 B.C.

“Wife: Cleopatra III

115 B.C., before April 6 establishment of Cleopatra III with Soter II

110 B.C., before October 31 expulsion of Soter II B.C., Alexander I on the throne

109 B.C., before February 2 return of Soter II

108 B.C., between March 10 and May 28 second interruption of Soter’s reign by Alexander I

Cleopatra III and Ptolemy X (Alexander I)

Ruler in Cyprus: 114/3 - 105/4 B.C.

“Ptolemy X (Alexander I) and Cleopatra Berenice

Wife: Cleopatra Berenice

107 B.C., before November 15 B.C., probably before September 19 expulsion of Soter

101 B.C., before October 26 death of Cleopatra III

88 B.C., soon before September 14 death of Alexander I B.C., return of Soter II

Ptolemy XI (Philometor Soter II) "Lathyrus"

restored (2nd B.C.

Wife: Cleopatra III

80 B.C., March death of Soter II

80 B.C. Cleopatra Berenice ruled for 6 months

succeeded by Alexander II B.C., who ruled for 19 days

80 B.C., before September 11 accession of Auletes

Late Ptolemies

Ptolemy XII

Ptolemy XII (Neos Dionysus) "Auletes

Wife: Cleopatra Berenice

58 B.C., after September 7 departure of Auletes from Egypt

Berenice IV

at first with Cleopatra Tryphaena

afterwards with Archelaus

57 B.C., before July 11 Berenice IV and Cleopatra Tryphaena on the throne

56 B.C., between February 1 and April 16 Archelaus married to Berenice IV

55 B.C., before April 22 return of Auletes

Ptolemy XII (Neos Dionysus)

"Auletes" B.C., res B.C.

52 B.C., September 5 association of Cleopatra VII and Ptolemy XIII with Auletes on the throne

51 B.C., between ca. February 1 and March 22 death of Auletes

Cleopatra VII (Philopator Nea Thea)

with Ptolemy XIII (Philopator): 52/1-47 B.C.

with Ptolemy XIV (Philopator): 47-44 B.C.

sole reign: 44-36 B.C.

coregency with Ptolemy XV (Caesar Philopator Philometor "Caesarion"): 36-30 involvement with Julius Caesar: 48 to 44 B.C.

involvement with Marc Antony: 41-30 B.C.

47 B.C., before January 15 death of Ptolemy XIII

44 B.C., between July and 2 September death of Ptolemy XIV

41 B.C. Caesarion temporarily on the throne

36 B.C. beginning of joint regency of Cleopatra & Caesarion

30 B.C., August 3 capture of Alexandria by Octavian

30 B.C., August 12 death of Cleopatra

30 B.C., August 31 beginning of Augustus’ reign

Alexander the Great

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: Alexander III, King of Macedonia, was the first king to be called "the Great". The son of Philip II and Olympias, Alexander was born in 356 B.C. He was taught by Aristotle and had a love for the works of Homer. Alexander became the King of Macedonia in 336 B.C. upon his father’s death. He took up his father’s war of aggression against Persia, adopting his slogan of a "Hellenic Crusade" against the barbarians. He defeated the small force defending Anatolia, proclaiming freedom for the Greek Cities, while keeping them under tight control. After a campaign through the Anatolian highlands (to impress the tribesmen), he met and defeated the Persian army under Darius III at Issue (near modern Iskenderun, Turkey). He occupied Syria and after a long siege of Tyre, Phoenicia, Alexander then entered Egypt, where he was accepted as pharaoh. He died in June 323 B.C. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Alexander received a hero's welcome in Egypt, an unhappy vassal of Persia for nearly 200 years. In Memphis, the Egyptian capital, Alexander was recognized as a pharaoh. Hieroglyphics of Alexander's adventures adorn temples in Luxor.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of Alexander's military campaign was the founding of Alexandria. Arrian wrote that "he himself designed the general layout of the new town, indicating the position of the market square, the number of temples...and the precise limits of its outer defenses." After Alexander died, Alexandria grew into the center of Hellenistic Greece and was the greatest city for 300 years in Europe and the Mediterranean.

In 331 B.C., Alexander the Great trekked 300 miles across the Sahara desert for no military reason to Siwa Oasis (near Libyan border), where he met with the oracle at the Zeus-Amum temple and asked questions about his future and divinity. The oracle greeted Alexander as the son of Amun-Re and gave him the favorable omens he wanted for an invasion of Asia. The 24-year-old Alexander arrived at Siwa by camel. He asked the oracle whether was the son of Zeus. He never revealed the answer to that question.

See Separate Article: ALEXANDER THE GREAT IN EGYPT AND GAZA europe.factsanddetails.com

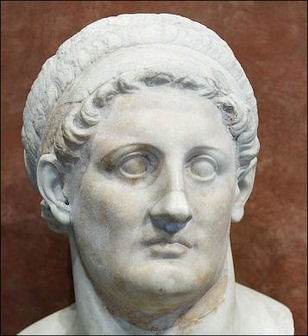

Ptolemy I

Ptolemy I Ptolemy I Soter (304-283 B.C.) took control of Egypt after Alexander the Great died. He was an ambitious self-made Macedonian general who served under Alexander and was also known as Ptolemy the savior. Ptolemy was crowned pharaoh in 304 B.C. on the anniversary of Alexander's death. He made offerings to the Egyptian gods, took an Egyptian throne name, and portrayed himself in pharaonic garb.

Ptolemy I was King of Egypt from 323 to 283 B.C. and the founder of the Ptolemic Dynasty. He distinguished himself as a trustworthy friend and ally and able troop commander under Alexander. During the council at Babylon, that followed Alexander’s death, he proposed that the huge territory conquered by Alexander be divided into provinces ruled his generals. He was awarded Egypt and became its governor and then its king and secured Egypt’s borders against external enemies. Ptolemy I is sometimes called Ptolemy I Soter. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Enriched by Alexander’s conquest in Asia and money earned from trade, Ptolemy I went on an unprecedented building spree. He inaugurated the great library of Alexandria and is believed to have planned the Pharos Lighthouse. He built many impressive temples, colonnaded streets, public baths and a massive gymnasium. He founded a the Mouseion, research institute with lecture halls, laboratories and guest room for visiting scholars, Archimedes and Euclid all worked there as did Aruistarchus of Samos who determined the sun was the center of solar system and the planets circled around it.

Ptolemy I made Alexandria the capital and cultural center of his kingdom. He gained the goodwill of the Egyptian people by restoring their temples and rituals, which had been destroyed and outlawed by the Persians and made gifts to the Egyptian gods, nobility and priestly caste. He also founded the Museum (Mouseion), a common workplace for scholars and artists, and established the famous library at Alexandria.

Ptolemy I and Alexander the Great

Ptolemy I was a Macedonian general and friend of Alexander since his early days. He served with Alexander from his first campaigns, and was the first ruler of the Ptolemy dynasty. He played a principal part in the campaigns in Afghanistan and India and participated in the Battle of Issus, commanding troops on the left wing under the authority of Parmenion. He accompanied Alexander during his journey to the Oracle in the Siwa Oasis and commanded the campaign that captured the rebel Bessus. During Alexander's campaign in the Indian subcontinent, Ptolemy was in command of the advance guard at the siege of Aornos and fought at the Battle of the Hydaspes River. [Source: Wikipedia]

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160):“The Macedonians consider Ptolemy to be the son of Philip, the son of Amyntas, though putatively the son of Lagus, asserting that his mother was with child when she was married to Lagus by Philip. And among the distinguished acts of Ptolemy in Asia they mention that it was he who, of Alexander's companions, was foremost in succoring him when in danger among the Oxydracae. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

When Alexander died Ptolemy somehow got his hands of Alexander's embalmed corpse (some say he stole it as it was being shipped back to Macedonia for burial). The body had been embalmed with honey. Ptolemy put the corpse in class coffin and had it displayed to the public. [Source: Lionel Casson, Smithsonian magazine, June 1985]

Ptolemy brought Alexander’s body to the northern coat of Egypt to shore up his claim on the region and boost his legitimacy. Ptolemy made Alexander’s tomb into one of the world’s first major tourist attractions and through it brought recognition to Alexandria. The corpse was exhibited in an elaborate mausoleum much as the bodies of Lenin and Mao are displayed in class cases in Moscow and Beijing. Tourist reportedly formed long lines to glimpse the famous Macedonian general's embalmed body. The body is thought to have remained there for six centuries and is thought to have maybe disappeared in riots in the A.D. 3rd century.

Egyptian Ptolemies

Ptolemy I After the Death of Alexander the Great

The account which follows deals with the troubled period which came after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C. The generals Antigonus, Ptolemy, Seleucus, Lysimachus and Cassander quarrelled over the division of the empire. Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): “After the death of Alexander, by withstanding those who would have conferred all his empire upon Aridaeus, the son of Philip, he became chiefly responsible for the division of the various nations into the kingdoms. He crossed over to Egypt in person, and killed Cleomenes, whom Alexander had appointed satrap of that country, considering him a friend of Perdiccas, and therefore not faithful to himself; and the Macedonians who had been entrusted with the task of carrying the corpse of Alexander to Aegae, he persuaded to hand it over to him. And he proceeded to bury it with Macedonian rites in Memphis, but, knowing that Perdiccas would make war, he kept Egypt garrisoned. And Perdiccas took Aridaeus, son of Philip, and the boy Alexander, whom Roxana, daughter of Oxyartes, had borne to Alexander, to lend color to the campaign, but really he was plotting to take from Ptolemy his kingdom in Egypt. But being expelled from Egypt, and having lost his reputation as a soldier, and being in other respects unpopular with the Macedonians, he was put to death by his body guard. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

“The death of Perdiccas immediately raised Ptolemy to power, who both reduced the Syrians and Phoenicia, and also welcomed Seleucus, son of Antiochus, who was in exile, having been expelled by Antigonus; he further himself prepared to attack Antigonus. He prevailed on Cassander, son of Anti pater, and Lysimachus, who was king in Thrace, to join in the war, urging that Seleucus was in exile and that the growth of the power of Antigonus was dangerous to them all. For a time Antigonus pre pared for war, and was by no means confident of the issue; but on learning that the revolt of Cyrene had called Ptolemy to Libya, he immediately reduced the Syrians and Phoenicians by a sudden inroad, handed them over to Demetrius, his son, a man who for all his youth had already a reputation for good sense, and went down to the Hellespont. But he led his army back without crossing, on hearing that Demetrius had been overcome by Ptolemy in battle. But Demetrius had not altogether evacuated the country before Ptolemy, and having surprised a body of Egyptians, killed a few of them. Then on the arrival of Antigonus Ptolemy did not wait for him but returned to Egypt.

“When the winter was over, Demetrius sailed to Cyprus and overcame in a naval action Menelaus, the satrap of Ptolemy, and afterwards Ptolemy him self, who had crossed to bring help. Ptolemy fled to Egypt, where he was besieged by Antigonus on land and by Demetrius with a fleet. In spite of his extreme peril Ptolemy saved his empire by making a stand with an army at Pelusium while offering resistance with warships from the river. Antigonus now abandoned all hope of reducing Egypt in the circumstances, and dispatched Demetrius against the Rhodians with a fleet and a large army, hoping, if the island were won, to use it as a base against the Egyptians. But the Rhodians displayed daring and ingenuity in the face of the besiegers, while Ptolemy helped them with all the forces he could muster. Antigonus thus failed to reduce Egypt or, later, Rhodes, and shortly afterwards he offered battle to Lysimachus, and to Cassander and the army of Seleucus, lost most of his forces, and was himself killed, having suffered most by reason of the length of the war with Eumenes. Of the kings who put down Antigonus I hold that the most wicked was Cassander, who although he had recovered the throne of Macedonia with the aid of Antigonus, nevertheless came to fight against a benefactor.

“After the death of Antigonus, Ptolemy again reduced the Syrians and Cyprus, and also restored Pyrrhus to Thesprotia on the mainland. Cyrene rebelled; but Magas, the son of Berenice (who was at this time married to Ptolemy) captured Cyrene in the fifth year of the rebellion. If this Ptolemy really was the son of Philip, son of Amyntas, he must have inherited from his father his passion for women, for, while wedded to Eurydice, the daughter of Antipater, although he had children he took a fancy to Berenice, whom Antipater had sent to Egypt with Eurydice. He fell in love with this woman and had children by her, and when his end drew near he left the kingdom of Egypt to Ptolemy (from whom the Athenians name their tribe) being the son of Berenice and not of the daughter of Antipater.

“This Ptolemy fell in love with Arsinoe, his full sister, and married her, violating herein Macedonian custom, but following that of his Egyptian subjects. Secondly he put to death his brother Argaeus, who was, it is said, plotting against him; and he it was who brought down from Memphis the corpse of Alexander. He put to death another brother also, son of Eurydice, on discovering that he was creating disaffection among the Cyprians. Then Magas, the half-brother of Ptolemy, who had been entrusted with the governorship of Cyrene by his mother Berenice — she had borne him to Philip, a Macedonians but of no note and of lowly origin — induced the people of Cyrene to revolt from Ptolemy and marched against Egypt.

“Ptolemy fortified the entrance into Egypt and awaited the attack of the Cyrenians. But while on the march Magas was in formed that the Marmaridae,a tribe of Libyan nomads, had revolted, and thereupon fell back upon Cyrene. Ptolemy resolved to pursue, but was checked owing to the following circumstance. When he was preparing to meet the attack of Magas, he engaged mercenaries, including some four thousand Gauls. Discovering that they were plotting to seize Egypt, he led them through the river to a deserted island. There they perished at one another's hands or by famine. Magas, who was married to Apame, daughter of Antiochus, son of Seleucus, persuaded Antiochus to break the treaty which his father Seleucus had made with Ptolemy and to attack Egypt.

When Antiochus resolved to attack, Ptolemy dispatched forces against all the subjects of Antiochus, freebooters to overrun the lands of the weaker, and an army to hold back the stronger, so that Antiochus never had an opportunity of attacking Egypt. I have already stated how this Ptolemy sent a fleet to help the Athenians against Antigonus and the Macedonians, but it did very little to save Athens. His children were by Arsinoe, not his sister, but the daughter of Lysimachus. His sister who had wedded him happened to die before this, leaving no issue, and there is in Egypt a district called Arsinoites after her.”

Ptolemy II and Other Ptolemic Rulers

Ptolemy II

The Ptolemic leaders have been characterized as wicked, self-indulgent hedonists who basked in luxury, bragged about their lineage and neglected their subjects. They were so obsessed about their bloodline they tended to marry their brothers and sisters. Problems caused by inbreeding are thought have been dealt with by infanticide and weak sons being propped up by the sister-wives who served as co-regents. The inbreeding is thought to be behind the fleshy bodies, prominent cheekbones and hawkish noses found on Ptolemies depicted on Roman coins.

The golden age of Hellenistic Greece occurred under the rule of Ptolemy II (309-246 B.C.), also known as Philadelphus (lover of his sister). Like ancient pharaohs he married his sister to solidify his power, an idea that horrified his Greek subjects. Ptolemy II Piladelphus Ptolemy II constructed the famous lighthouse on the island of Pharos, off Alexandria, which was one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. He expanded the Alexandria Library. Eratosthenes measured the Earth’s circumference under his reign, The Ptolemies also built botanical and zoological gardens for rare species.

“Ptolemy III Euergetes I (246–221 B.C.) took an interest in Palestine and came into conflict there with the Seleucid Dynasty of Syria. The Syrian wars, combined with feuds among the Ptolemies and native rebellions in the south, weakened Ptolemaic authority. In 170 B.C., Rome intervened on behalf of the Ptolemies against the Seleucid king, Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175–164 B.C.), and as a result Egypt entered more and more into the orbit of the Roman Republic. [Source: New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003]

Cleopatra I (193-167 B.C.) was the first Ptolemic queen (she is not be confused with the famous great-great-granddaughter Cleopatra VI). She ruled ably and ruthlessly. There other queens. Some of them were Selucids (Greeks from Syria).

Famed Cleopatra was actually Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator. The last pharaoh of Egypt, she was the daughter of Ptolemy XII. Cleopatra is Greek for “glory to her race.” Her attempts to maintain Egypt’s independence and renew its glory were doomed. All the great civilizations of the ancient Mediterranean world were now submitting to the indisputable power of Rome. Some African-American groups claim that Cleopatra was a black woman. There is this little evidence to back this up. However Ptolemy XII had a mysterious concubine who could have been black and could have given birth to Cleopatra although it is very unlikely. (See Separate article on Cleopatra).

Ptolemy XII was as known the “Flute Player” because of his musical talent and his ability to charms the ladies — and the boys — with his playing and his taste for things he liked to stick in his mouth. Cleopatra’s great-grand father was known as Ptolemy Physkon (“Potbelly”). He reportedly paraded around in flimsy robes to show off his flab (at that time regarded as sign of wealth).

Great Spectacle and Procession of Ptolemy II (285 B.C.)

The historian William Stearns Davis wrote: “When Ptolemy II Philadelphus became king of Egypt (285 B.C.), he celebrated his accession by a magnificent procession and festival at Alexandria. The following is only a part of the description of the very elaborate spectacle. The mere enumeration of all this pomp, power and treasure conveys a striking idea of the riches of the Ptolemaic kings, the splendor of their court, and the resources of their kingdom. [Source: William Stearns Davis, “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols., (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-1913), Vol. I: Greece and the East, pp. 329-332.

Roman-era procession for Dionysus

Around A.D. 200, Athanaeus, a Roman-era Greek rhetorician, wrote in “The Great Spectacle and Procession of Ptolemy II Philadelphus: History, Book V, Chap. 25: “First I will describe the tent prepared inside the citadel, apart from the place provided to receive the soldiers, artisans, and foreigners. For it was wonderfully beautiful, and worth talking of. Its size was such that it could accommodate one hundred and thirty couches [for banqueters] arranged in a circle. The roof was upborne on wooden pillars fifty cubits high of which four were arranged to look like palm trees. On the outside of the pillars ran a portico, adorned with a peristyle on three sides with a vaulted roof. Here it was the feasters could sit down. The interior of this was surrounded with scarlet curtains; in the middle of the space, however, were suspended strange hides of beasts, strange both for their variegated color, and their remarkable size. The part which surrounded this portico in the open air was shaded by myrtle trees and laurels, and other suitable shrubs.

“As for the whole floor, it was strewed with every kind of flower; for Egypt, thanks to its mild climate, and the fondness of its people for gardening, produces abundantly, and all the year round, those flowers which are scarce in other lands, and then come only at special seasons. Roses, white lilies, and many another flower never lack in that country. Wherefore, although this entertainment took place in midwinter, there was a show of flowers that was quite incredible to the foreigners. For flowers of which one could not easily have found enough to make one chaplet in any other city, were here in vast abundance, to make chaplets for the guests . . . and were thickly strewn over the whole floor of the tent; so as really to give the appearance of a most divine meadow.

“By the posts around the tent were placed animals carved in marble by the first artists, a full hundred in number; while in the spaces between the posts were hung pictures by the Sicyonian painters. And alternately with these were carefully selected images of every kind, and garments embroidered with gold and splendid cloaks, some having portraits of the kings of Egypt wrought upon them, and some stories from mythology. Above these were placed gold and silver shields alternately. [A long account follows of the golden couches, golden tripods, silver dishes, and lavers, jewel-set cups, etc., provided for the guests.]

“And now to go on to the shows and processions exhibited; for they passed through the Stadium of the city. First of all there went the procession of Lucifer [the name given to the planet Venus] for the fˆte began at the time when that star first appears. Then came processions in honor of the several gods. In the Dionysus procession, first of all went the Sileni to keep off the multitude, some clad in purple cloaks, and some in scarlet ones. These were followed by Satyrs, bearing gilded lamps made of ivy wood. After them came images of Victory, having golden wings, and they bore in their hands incense burners, six cubits in height, adorned with branches made of ivy wood and gold, and clad in tunics embroidered with figures of animals, and they themselves also had a deal of gold ornament about them. After them followed an altar six cubits high, a double altar, all covered with gilded ivy leaves, having a crown of vine leaves upon it all in gold. Next came boys in purple tunics, bearing frankincense and myrrh, and saffron on golden dishes. And then advanced forty Satyrs, crowned with golden ivy garlands; their bodies were painted some with purple, some with vermilion, and some with other colors. They wore each a golden crown, made to imitate vine leaves and ivy leaves. Presently also came Philiscus the Poet, who was a priest of Dionysus, and with him all the artisans employed in the service of that god; and following were the Delphian tripods as prizes to the trainers of the athletes, one for the trainer of the youths, nine cubits high, the other for the trainer of the men, twelve cubits.

“The next-was a four-wheeled wagon fourteen cubits high and eight cubits wide; it was drawn by one hundred and eighty men. On it was an image of Dionysus — ten cubits high. He was pouring libations from a golden goblet, and had a purple tunic reaching to his feet. . .In front of him lay a Lacedaemonian goblet of gold, holding fifteen measures of wine, and a golden tripod, in which was a golden incense burner, and two golden bowls full of cassia and saffron; and a shade covered it round adorned with ivy and vine leaves, and all other kinds of greenery. To it were fastened chaplets and fillets, and ivy wands, drums, turbans, and actors' masks. After many other wagons came one twenty-five cubits long, and fifteen broad; and this was drawn by six hundred men. On this wagon was a sack, holding three thousand measures of wine, and consisting of leopards' skins sewn together. This sack allowed its liquor to escape, and it gradually flowed over the whole road. [An endless array of similar wonders followed; also a vast number of palace servants displaying the golden vessels of the king; twenty-four chariots drawn by four elephants each; the royal menagerie — twelve chariots drawn by antelopes, fifteen by buffaloes, eight by pairs of ostriches, eight by zebras; also many mules, camels, etc., and twenty-four lions.]

“After these came a procession of troops — both horsemen and footmen, all superbly armed and appointed. There were 57,600 infantry, and 23,200 cavalry. All these marched in the procession. . .all in their appointed armor. . .The cost of this great occasion was 2239 talents and 50 minae [roughly $100 million in 2018 dollars — a kingly sum for any coronation].”

Alexandria's main boulevard

Arsinoe II

Arsinoë II (316-271 B.C.) was a Ptolemaic Queen and co-regent of Ancient Egypt and is regarded as the third ruler of Ptolemic Egypt. One of the great queens of the Ptolemaic Period, she was a strong-minded and influential ruler with her brother-husband Ptolemy II. In a famous image she wears a unique vulture headdress and is shown shaking a sistrum, or rattle, with the cow's head of the goddess Hathor. This relief was probably made after her death when she had been made a goddess and was called the "daughter of the god Amun."

Chris Carpenter of Minnesota State University, Mankato wrote: “The story of Arsinoe II's life is much like a Greek tragic play. It is filled with death, greed, and intrigue. Arsinoe II (316-271 B.C.) was the daughter of King Ptolemy I and was married to King Lysimachus of Thrace at sixteen years of age. Now, at this time, her life was going exceptional well, she gave her husband three boys and in return she got whatever she wanted. Unfortunately, all good things come to an end. [Source: Chris Carpenter, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“When her husband died, she was offered a deal by a potential second mate. If she married him, she was promised to rule Thrace. This marriage, however, was a scam. Her second husband only wanted to get close to her sons to kill them. When he had succeeded in killing two of her sons and the third fled for his life, she returned to her homeland with a plan to gain power in Egypt. When she got there however, she was welcomed by a technicality that could destroy her plan.+\

“King Ptolemy I, Arsinoe's father had a son (Ptolemy II) the current king of Egypt. If that is not surprisingly enough, he was married to King Lysimachus' daughter Arsinoe I (282-247 B.C.). This little discovery put as kink in her plans, but Arsinoe II started to romance and win her brother's heart. By the year 278 B.C. Ptolemy II saw his wife, Arsinoe I as a threat, and he accused her of complicity in a plot to have him killed. Consequently, she was banished to Coptos in Upper Egypt. Arsinoe II took this opportunity and shortly afterward married her brother in accordance with Egyptian royal customs. Thus fulfilling the role of stepmother and sister-in-law to Arsinoe I. +\

“As a result of her new-found husband, she quickly became the true ruler of the country and was a key figure in court politics. Like all devoured by power and greed, once you taste it you want more. She was given divine statues and coinage was issued in her name, but it did not stop there. She wanted to reach the status of a goddess and actively pushed Arsinoe worship to achieve this task. Throughout this whole time she never gave her husband any children due to her personal philosophy. She believed that they only grew up and plotted and executed the deaths of their parents. In the end she died at the age of forty-five, thus, leaving us to ponder what she may have arose to if she had lived longer. Ptolemy II built a shrine and had many cities named for her after death. So as you can see, the life of Arsinoe II was that of a tragic tale.” +\

Ptolemy VI’s Power Struggle with His Mother Cleopatra I

Ptolemy VI

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): “The one called Philometor is eighth in descent from Ptolemy son of Lagus, and his surname was given him in sarcastic mockery, for we know of none of the kings who was so hated by his mother. Although he was the eldest of her children she would not allow him to be called to the throne, but prevailed on his father before the call came to send him to Cyprus. Among the reasons assigned for Cleopatra's enmity towards her son is her expectation that Alexander the younger of her sons would prove more subservient, and this consideration induced her to urge the Egyptians to choose Alexander as king.” [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

“When the people offered opposition, she dispatched Alexander for the second time to Cyprus, ostensibly as general, but really because she wished by his means to make Ptolemy more afraid of her. Finally she covered with wounds those eunuchs she thought best disposed, and presented them to the people, making out that she was the victim of Ptolemy's machinations, and that he had treated the eunuchs in such a fashion. The people of Alexandria rushed to kill Ptolemy, and when he escaped on board a ship, made Alexander, who returned from Cyprus, their king.1.9.3

“Retribution for the exile of Ptolemy came upon Cleopatra, for she was put to death by Alexander, whom she herself had made to be king of the Egyptians. When the deed was discovered, and Alexander fled in fear of the citizens, Ptolemy returned and for the second time assumed control of Egypt. He made war against the Thebans, who had revolted, reduced them two years after the revolt, and treated them so cruelly that they were left not even a memorial of their former prosperity, which had so grown that they surpassed in wealth the richest of the Greeks, the sanctuary of Delphi and the Orchomenians. Shortly after this Ptolemy met with his appointed fate, and the Athenians, who had been benefited by him in many ways which I need not stop to relate, set up a bronze likeness of him and of Berenice, his only legitimate child.”

Cleopatra VII

Cleopatra VII

The person we know today as Cleopatra was officially named Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator Her birth name was Cleopatra netjeret mer-it-es “Goddess Beloved of Her Father”. In many respects she was The Last Pharaoh of Egypt, ruling Egypt from 51 to 30 B.C. when it was ruled by the Greek Ptolemies of which Cleopatra was a member. When Rome took over Egypt during the last days of her reign, her life and reign came to an end as did Ptolemic Egypt, which had been founded by Alexander’s general, Ptolemy, in 326 BC..

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “Cleopatra the VII, also known as Cleopatra the VI, was queen of Egypt from 51 to 30 B.C. She was the daughter of Ptolemy XI. She was co-regent of Egypt from 51 to 49 B.C., but was dethroned by Ptolemy XII, from the year 49 to 48 B.C. She was reinstated to the throne following Julius Caesar's defeat of Ptolemy XII. She remained as co-regent with her brother Ptolemy XIII, from 47 to 44 B.C. Following this, she became mistress to Julius Caesar, living with him in Rome from 46 to 44 B.C. Eventually, she returned to Egypt and murdered Ptolemy XIII in 44 B.C. She then met Mark Anthony (a popular love story through out the ages), in 36 B.C. In 31 B.C. Octavian's army defeated Mark Anthony at the battle of Actium. Cleopatra and Mark Anthony fled, however, Cleopatra returned to Egypt and unsuccessfully attempted to seduce Octavian. According to legend she died of a bite by an asp to avoid being captured by Octavian. Cleopatra lived from 69 to 30 B.C.” [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “Cleopatra was of Macedonian descent and not a native Egyptian. She was the second daughter of King Ptolemy XII. Historical accounts of Cleopatra tell of a beautiful, highly educated woman who was schooled in physics, alchemy, and astronomy, and could speak many languages. Her voice, said the Greek biographer Plutarch, “was like an instrument of many strings, which could pass from one language to another.” [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

One historian wrote: “'For Rome, who had never condescended to fear any nation or people, did in her time fear two human beings; one was Hannibal, and the other was a woman.' In Roman literature during her lifetime and just after her death, Cleopatra represented the dangerous appeal of decadence and corruption. A highly educated Greek, with the wealth of Egypt at her disposal, she was mistress of first of Julius Caesar and then of Mark Antony.”

Cleopatra VII (Philopator Nea Thea)

with Ptolemy XIII (Philopator): 52/1-47 B.C.

with Ptolemy XIV (Philopator): 47-44 B.C.

sole reign: 44-36 B.C.

coregency with Ptolemy XV (Caesar Philopator Philometor "Caesarion"): 36-30 involvement with Julius Caesar: 48 to 44 B.C.

involvement with Marc Antony: 41-30 B.C.

47 B.C., before January 15 death of Ptolemy XIII

44 B.C., between July and 2 September death of Ptolemy XIV

41 B.C. Caesarion temporarily on the throne

36 B.C. beginning of joint regency of Cleopatra & Caesarion

30 B.C., August 3 capture of Alexandria by Octavian

30 B.C., August 12 death of Cleopatra

30 B.C., August 31 beginning of Augustus’ reign

See Separate Article: CLEOPATRA (69-30 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024