Home | Category: Themes, Early History, Archaeology

GEOGRAPHY OF EGYPT

Bordered by the Red Sea and Israel to the east, Sudan to the south, Libya to the west and the Mediterranean Sea to the north, modern Egypt is a 100,140 square kilometers (386,650 square miles) in area, or roughly the twice the size of California. Only 2.6 percent of the country is good for agriculture (compared to 21 percent in the U.S.) and most of this land is located in the Nile Delta and along the Nile Valley. There are no forests in Egypt. There are some barren mountains in the southern Sinai and running parallel to the Red Sea. Egypt’s deserts have little or no vegetation and are very hot. The deserts provided a natural barrier against invaders. Oases provided dates, olives and wine.

Modern Egypt is roughly square in shape, measuring 1040 kilometers (640 miles) from north to south, and 980 kilometers (600 miles) from east to west in the north and 1240 kilometers (760 miles) from east to west in the south. The entire length of Egypt is framed in rocky walls, which sometimes reach a height of 200 to 250 meters (660 to 800 feet). These limestone features are not mountains in our sense of the word. Instead of rising to peaks, they form the edge of a large tableland with higher plateaus here and there. This table-land is entirely without water, and is covered by desert. Rare, strong rains have carved out wadis and channels in the landscape. A barren plateau in western Egypt joins the the Sahara. About 150 kilometers (95 miles) from the Nile, running parallel with it, are some remarkable dips in this table-land. These "oases" are well watered and very fruitful, but with these exceptions there is little or no vegetation in this region, known since olden times as the Libyan desert.

Modern Egypt has about 2930 kilometers (1,800 miles) of coastline: 980 kilometers (600 miles) along the Mediterranean Sea and 1950 kilometers (1,200 miles) along the Red Sea. The Suez Canal is located to the west of the Sinai. It connects the Mediterranean Sea and the Gulf of Suez (the Red Sea).

The names of the places in ancient Egypt inscribed in tombs give us many interesting particulars. Most are names derived from their chief products: “fish, cake, sycamore, wine, lotus, provision of bread, “provision of beer, fish-catching," etc., and as these designations might repeat themselves, the name of the master is added: — “the fish-catching of Tehen," “the lotus of Pchen," “the lake of Enchefttka," “the lake of Ra'kapu," etc. Some proprietors prefer religious names, thus S'abu, high priest of Ptah, named his villages: “Ptah gives life," "Ptah gives everlasting life," "Ptah acts rightly," "Ptah causes to grow,"' etc. Others again loyally choose names of kings: such as a Itahhotep called his villages: “Sahure gives beautiful orders," “'Es'e, who loves the truth," “Horus wills that U. scrkaf should live," “Mut wills that Kakae should live," “Harekau has splendid diadems," “Harekau gives splendid rewards.[Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Atlas of Ancient Egypt” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

“The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Egypt” by Bill Manley (1997) Amazon.com;

“Geography Matters in Ancient Egypt” by Melanie Waldron (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Nile: Traveling Downriver Through Egypt's Past and Present” by Toby Wilkinson (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Nile: History's Greatest River” by Terje Tvedt (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Gift of the Nile?: Ancient Egypt and the Environment (Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections) by Egyptian Expedition, Thomas Schneider, Christine L. Johnston (2020) Amazon.com;

“Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Cultivated Plants in West Asia, Europe, and the Nile Valley” by Daniel Zohary and Maria Hopf (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Nile and Ancient Egypt: Changing Land- and Waterscapes, from the Neolithic to the Roman Era”, Illustrated by Judith Bunbury (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com; Wilkinson is a fellow of Clare College at Cambridge University;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: An Illustrated Reference to the Myths, Religions, Pyramids and Temples of the Land of the Pharaohs” by Lorna Oakes (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” (DK Eyewitness Books) by George Hart (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization” by Barry Kemp (1989, 2018) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“Temples, Tombs, and Hieroglyphs: A Popular History of Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz (1978, 2009) Amazon.com;

“Egypt” (Insiders) by Joyce Tyldesley (2001) Amazon.com;

Main Geographical Features of Egypt

Nile Valley is 1510 kilometers (930 miles) long and varies in width from three to 16 kilometers (two to 10 miles). Stretching the length of Egypt from north to south and occupying a depression around the Nile River, it occupies 3 percent of Egypt's land but is home to 96 percent of its people. The majority of Egyptians live around the Nile. For them the desert is almost as alien an environment as snow-capped mountains.

Nile Delta is a very fertile area between Cairo and the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's most intensely cultivated piece of land. It covers 15,500 square kilometers (6,000 square miles) and is about a 160 kilometers (100 miles) in length from north to south and 150 miles (240 kilometers) wide at its widest point.

Western Desert is to the west of the Nile. Covering 68 percent of Egypt, it is mostly a flat, sand- and gravel-covered, barren wasteland that rarely exceeds 200 meters (600 feet) above sea level. It extends from the Nile Valley to Libya and from the Mediterranean Sea to Sudan. Most of its people live in and around five major oases. To the east of Nile is the Eastern Desert, which is made up large of a plateau extending from the Nile to the Red Sea, with some hills and a ridge of mountains on the Red Sea side. Most of the people in this region live along the Red Sea.

Sinai peninsula is a triangular piece of land between the Gulf of Suez and the Gulf of Aqaba (branches of the Red Sea) and the Mediterranean and Israel. Egypt's highest peak, 2643 meter (8,668-foot-high) -high Mount Catherine, is located on the Sinai. Nearby is 2285 meter (7,497-foot) -high Mt. Sinai. The presence of charcoal at sites in Giza is viewed as evidence that trees once grew around there.

Geography of Ancient Egypt

The inhabited part of ancient Egypt was relatively small — about 920 kilometers (570 miles) in length and only embracing about 32,375 square kilometers (12,500 square miles), an area somewhat smaller than Belgium. Even including the 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles) between the first cataract and Khartoum, this would only increase the kingdom of Egypt by about 2,920 square kilometers (1,125 square miles) as the valley here is very narrow. It was the exceeding fertility of the available land which made Egypt such a vital place. [Source: Life in Ancient Egypt by Adolph Erman, 1894]

The inhabited part of ancient Egypt was relatively small — about 920 kilometers (570 miles) in length and only embracing about 32,375 square kilometers (12,500 square miles), an area somewhat smaller than Belgium. Even including the 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles) between the first cataract and Khartoum, this would only increase the kingdom of Egypt by about 2,920 square kilometers (1,125 square miles) as the valley here is very narrow. It was the exceeding fertility of the available land which made Egypt such a vital place. [Source: Life in Ancient Egypt by Adolph Erman, 1894]

The two parts of ancient Egypt were very different. The larger Lower Egypt — the Nile Delta area, near the Mediterranean Sea, is a broad swamp intersected with canals. The climate is influenced by the sea, and there is a regular rainy season in the winter. The smaller Upper Egypt — Nile Valley — has relatively little rain, and it has one great waterway, with a few stagnant branches and canals.

The landscape of ancient Egypt differed little from that of modern Egypt except that it was probably more swampy than now. The dry climate of the south was favorable to cultivation as long as flooding and irrigation provided enough water. The Delta area in the north required centuries of work to convert the swamps to arable land. The brackish waters of Lake Manzala now covers an area about 1,200 square kilometers, but in ancient times part of this district was one of the most productive parts of Egypt.

Under the New Kingdom (about 1,300 B.C.) progress seems to have been made developing the area east of the Nile Delta, which rose to importance, through being the highway to Syria. The the old town of Tanis became a capital, and other towns were founded at different places. The west of the Delta was in a great measure in the hands of the Libyan nomads till the seventh century B.C., when the chief town Sais became the seat of government under the family of Psammetichus, and after the foundation of Alexandria by Alexander the Great in the 3rd century B.C., this new city became a major city for a thousand years. Even as late as the Middle Ages the "Iushmur", a swampy district, was scarcely accessible; it was inhabited by an early non-Egyptian people, with whom neither the Greek or the Arab rulers had much to do.

Stretched Out Geography of Ancient Egypt

The populated areas of ancient Egypt were fairly dense but stretched out north-to-south along the Nile. We should expect the inhabitants, when so closely crowded together, to be essentially welded into one nation, but the length of Egypt prevented this result; the inhabitants of one district had neighbours on two sides only, and the people of the Delta had a wearisome journey before reaching Upper Egypt. Therefore we find in Egypt the development of individual townships, reminding us strongly of early conditions of life in Germany. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Each district or province had its chief god and its own traditions; the inhabitants were often at war with their neighbours, and when the central government was weak, the kingdom became subdivided into small principalities.

The districts were of very small extent, the average size of those of Upper Egypt about 700 square kilometers (270 square miles); those of the Delta were rather larger, yet these provinces were of more importance than their size would indicate, as the population of each would probably average 300,000 people.

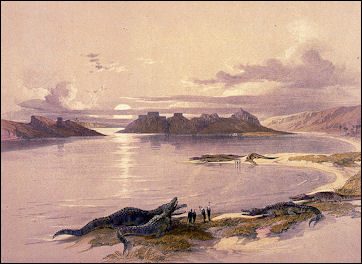

The natural boundary of Egypt on the south was always the so-called first cataract, those rapids were 11 kilometers (seven miles) long, on the 24th degree of latitude, where the Nile breaks through the mighty granite barrier. The district of the cataract was inhabited in old times as at present by Nubians, a non-Egyptian people, and the sacred island of Philae at the southern end of the cataract, where the later Egyptians revered one of the graves of Osiris, is in fact Nubian soil. These rapids were of the highest importance for strategic purposes, and the early Egyptians strongly fortified the town of Aswan on the east bank so as to be able to blockade the way into Egypt by land, as well as to protect the quarries where from the earliest ages they obtained all their splendid red granite for obelisks and other monuments. The buildings in Egypt occupied so much of the attention of the state that immense importance was attached to the unobstructed working of these quarries.

Upper and Lower Egypt

Upper Egypt refers to southern Egypt, specifically to the Nile Valley south of Cairo. Lower Egypt refers to northern Egypt, usually the Nile Delta, north of Cairo. The regions are so named because Upper Egypt is along the upriver section of the Nile and Lower Egypt is located on the down river section of the Nile. The Nile flows from south to north.

Throughout its history, Egypt has been characterized by a rivalry between Lower Egypt and Upper Egypt. Many tomb and temple paintings and inscriptions feature pharaohs wearing either: 1) an Upper Egypt crown (a large, white, conehead-type headdress); 2) a Lower Egypt crown (a red headdress that looks bottle stopper with a spike rising from the back); or 3) an Upper and Lower Egypt crown (a combination of the two aforementioned crowns). The later symbolized the unification of the two regions.

In very ancient times, between Upper and Lower Egypt were separated politically; they spoke two different dialects; and though they honored several identical gods under different names, others were unique to each region. This contrast between Upper and Lower Egypt was emphasized in many ways by their gods. Each was the protection of different goddesses: Lower Egypt was under that of the snake goddess Wadjet, while Upper Egypt was ruled by a different snake goddess. In mythical ages the land was given to different gods as a possession; Lower Egypt to Set, Upper Egypt to Horus. [Source: Life in Ancient Egypt by Adolph Erman, 1894]

The concept of two lands did not disappear when Upper and Lower Egypt were united around 3100 B.C. According to National Geographic: Rather, the dual nature of the Egyptian kingdom was emphasized, as duality was an important tenet of Egyptian culture, including the throne itself. Later 1st dynasty pharaohs would embrace the title “Ruler of the Two Lands,” and following pharaohs would continue to use the title through the ages. Keeping the identities of the two lands distinct from each other was a way of giving the new political order a divine sanction. Central to ancient Egyptian belief were two opposite and necessary forces—ma’at (order) and isfet (chaos), the static and dynamic forces that govern the universe. Balance was desired, and order and chaos must coexist in order for equilibrium to be achieved. [Source: National Geographic, National Geographic, June 10, 2022]

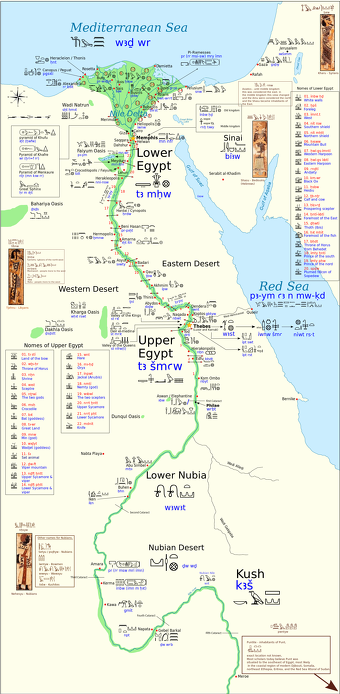

Nomes (Provinces) of Ancient Egypt

Herodotus

Upper Egypt was divided times into about twenty provinces or nomes as they were called by the Greeks; the division of the Delta into the same number is an artificial one of later date, as is proved by there being the same number for a country a quarter as large again. The official list of these provinces varied at different times, sometimes the same tract of land is represented as an independent province, and sometimes as a subdivision of that next to it. The provinces were government districts, and these might change either with a change of government or for political reasons, but the basis of this division of the country was always the same, and was part of the flesh and blood of the nation. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The names of the nomes varied. Some appear to have naturally occurred. In Upper Egypt we find: the province of the “hare," of the “gazelle," two of the “sycamore," two of the “palm," one of the “knife," whilst the most southern portion was called simply the "land in front. " In the Delta the home of cattle-breeding we find the province of the ''black ox," of the "calf," etc. Other names were derived from the religion; thus the second nome of Upper Egypt was called "the scat of lions," the sixth "his mountain," and the twelfth in the Delta was named after the god Thoth.

Each province possessed its coat-of-arms, derived either from its name or its religious myths; this was borne on a pole before the chieftain on solemn occasions. The shield of the hare province explains itself; that of the eighth nome was Jg , the little chest in which the head of Osiris, the sacred relic of the district, was kept. The twelfth province had for a coat-of-arms, signs which signify “his mountain ".

Herodotus on the Geography of Egypt

Fifth Century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “Beyond and above Heliopolis, Egypt is a narrow land. For it is bounded on the one side by the mountains of Arabia, which run north to south, always running south towards the sea called the Red Sea. In these mountains are the quarries that were hewn out for making the pyramids at Memphis. This way, then, the mountains run, and end in the places of which I have spoken; their greatest width from east to west, as I learned by inquiry, is a two months' journey, and their easternmost boundaries yield frankincense. Such are these mountains. On the side of Libya, Egypt is bounded by another range of rocky mountains among which are the pyramids; these are all covered with sand, and run in the same direction as those Arabian hills that run southward. Beyond Heliopolis, there is no great distance—in Egypt, that is:8 the narrow land has a length of only fourteen days' journey up the river. Between the aforesaid mountain ranges, the land is level, and where the plain is narrowest it seemed to me that there were no more than thirty miles between the Arabian mountains and those that are called Libyan. Beyond this Egypt is a wide land again. Such is the nature of this country. 9. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“From Heliopolis to Thebes is nine days' journey by river, and the distance is six hundred and eight miles, or eighty-one schoeni. This, then, is a full statement of all the distances in Egypt: the seaboard is four hundred and fifty miles long; and I will now declare the distance inland from the sea to Thebes : it is seven hundred and sixty-five miles. And between Thebes and the city called Elephantine there are two hundred and twenty-five miles. 10.

“The greater portion, then, of this country of which I have spoken was land deposited for the Egyptians as the priests told me, and I myself formed the same judgment; all that lies between the ranges of mountains above Memphis to which I have referred seemed to me to have once been a gulf of the sea, just as the country about Ilion and Teuthrania and Ephesus and the plain of the Maeander, to compare these small things with great. For of the rivers that brought down the stuff to make these lands, there is none worthy to be compared for greatness with even one of the mouths of the Nile, and the Nile has five mouths. There are also other rivers, not so great as the Nile, that have had great effects; I could rehearse their names, but principal among them is the Achelous, which, flowing through Acarnania and emptying into the sea, has already made half of the Echinades Islands mainland. 11.

Herodotus Map of Lower Egypt

Herodotus on the Red Sea and Arabia

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: Now in Arabia, not far from Egypt, there is a gulf extending inland from the sea called Red9 , whose length and width are such as I shall show: in length, from its inner end out to the wide sea, it is a forty days' voyage for a ship rowed by oars; and in breadth, it is half a day's voyage at the widest. Every day the tides ebb and flow in it. I believe that where Egypt is now, there was once another such gulf; this extended from the northern sea towards Aethiopia, and the other, the Arabian gulf of which I shall speak, extended from the south towards Syria; the ends of these gulfs penetrated into the country near each other, and but a little space of land separated them. Now, if the Nile inclined to direct its current into this Arabian gulf, why should the latter not be silted up by it inside of twenty thousand years? In fact, I expect that it would be silted up inside of ten thousand years. Is it to be doubted, then, that in the ages before my birth a gulf even much greater than this should have been silted up by a river so great and so busy? 12. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“As for Egypt, then, I credit those who say it, and myself very much believe it to be the case; for I have seen that Egypt projects into the sea beyond the neighboring land, and shells are exposed to view on the mountains, and things are coated with salt, so that even the pyramids show it, and the only sandy mountain in Egypt is that which is above Memphis; besides, Egypt is like neither the neighboring land of Arabia nor Libya, not even like Syria (for Syrians inhabit the seaboard of Arabia); it is a land of black and crumbling earth, as if it were alluvial deposit carried down the river from Aethiopia; but we know that the soil of Libya is redder and somewhat sandy, and Arabia and Syria are lands of clay and stones. 13.

Herodotus on Nile Delta and Upper and Lower Egypt

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “We leave the Ionians' opinion aside, and our own judgment about the matter is this: Egypt is all that country which is inhabited by Egyptians, just as Cilicia and Assyria are the countries inhabited by Cilicians and Assyrians, and we know of no boundary line (rightly so called) below Asia and Libya except the borders of the Egyptians. But if we follow the belief of the Greeks, we shall consider all Egypt commencing from the Cataracts and the city of Elephantine12 to be divided into two parts, and to claim both the names, the one a part of Libya and the other of Asia. For the Nile, beginning from the Cataracts, divides Egypt into two parts as it flows to the sea. Now, as far as the city Cercasorus the Nile flows in one channel, but after that it parts into three. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“One of these, which is called the Pelusian mouth, flows east; the second flows west, and is called the Canobic mouth. But the direct channel of the Nile, when the river in its downward course reaches the apex of the Delta, flows thereafter clean through the middle of the Delta into the sea; in this is seen the greatest and most famous part of its waters, and it is called the Sebennytic mouth. There are also two channels which separate themselves from the Sebennytic and so flow into the sea: by name, the Saïtic and the Mendesian. The Bolbitine and Bucolic mouths are not natural but excavated channels. 18.

“The response of oracle of Ammon in fact bears witness to my opinion, that Egypt is of such an extent as I have argued; I learned this by inquiry after my judgment was already formed about Egypt. The men of the cities of Marea and Apis, in the part of Egypt bordering on Libya, believing themselves to be Libyans and not Egyptians, and disliking the injunction of the religious law that forbade them to eat cows' meat, sent to Ammon saying that they had no part of or lot with Egypt: for they lived (they said) outside the Delta and did not consent to the ways of its people, and they wished to be allowed to eat all foods. But the god forbade them: all the land, he said, watered by the Nile in its course was Egypt, and all who lived lower down than the city Elephantine and drank the river's water were Egyptians. Such was the oracle given to them. 19.

The Nile

The Nile in modern Egypt extends for 600 miles between Aswan in southern Egypt to the Mediterranean Sea. South of Aswan, breaking up the river and extending south Sudan, is 300-mile-long Lake Nasser, a reservoir created by the Aswan High Dam. The Nile is made up of the Blue Nile (originating in Ethiopia) and the White Nile (originating in Burundi in Central Africa) which combine to form the Nile in the Sudan. North of Cairo is the Nile Delta. Here the Nile splits several tributaries, the largest ones being the Rosseta

Nomes of Lower Egypt: Nome 1: White Walls Nome; Nome 2: Travellers land; Nome 3: Cattle land; Nome 4: Southern shield land; Nome 5: Northern shield land; Nome 6: Mountain bull land; Nome 7: West harpoon land; Nome 8: East harpoon land; Nome 9: Andjety god land; Nome 10: Black bull land; Nome 11: Heseb bull land; Nome 12: Calf and Cow land; Nome 13: Prospering Sceptre land; Nome 14: Eastmost land; Nome 15: Ibis-Tehut land; Nome 16: Fish land; Nome 17: The throne land; Nome 18: Prince of the South land; Nome 19: Prince of the North land; Nome 20: Sopdu-Plumed Falcon land

The Nile River is the longest river in the world as every school child knows. Extending for 4,145 miles from its source in the central African to the Mediterranean Sea, its drainage area encompasses nearly a tenth of Africa and covers an estimated 1,293,000 square miles in nine countries. According to the Guinness Book of Records, if the Pará estuary is counted, the Amazon is 4,195 miles long, which make it longer mile Nile River, which lost a few miles after the construction the Aswan Dam. The flow of the Amazon is 60 times greater than the flow of the Nile.

The Nile begins in places with abundant rain but passes through areas that are dry and barren. In these places the Nile is like a long oasis bringing water, food, and life to places that otherwise would have none of these things. An ancient Egyptian hymn goes: “Hail to you, O Nile, rushing from the earth and giving life to Egypt.” Without the Nile, Ancient Egypt may never have become the great civilization it became nor lasted as long as it did.

See Separate Article: THE NILE: ROUTES, SOURCES, HISTORY, FLOOD africame.factsanddetails.com THE NILE AND ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Flora in Ancient Egypt

From the fertility of the Egyptian soil we might expect a specially rich flora, but notwithstanding the luxuriant vegetation, yet no country in the same latitude has so poor a variety of plants. There are very few trees. The sycamore or wild fig and the acacia are the only common forest trees, and these grow in an isolated fashion. Besides these there are fruit trees, such as the date and dom palms, the fig tree, and others. The scarcity of wood is quite a calamity for Egypt. It is the same with plants; herbs and vegetables reign in this land of cultivation. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Karl Benjamin Klunzinger (1834-1914) said: "In this country, wherever a spot exists where wild plants could grow (such as irrigated ground), the agriculturist comes, sows his seed and weeds out the wild flowers. There are also no alpine nor forest plants, no heather, no plants common to ruins, bogs, or lakes, partly because there are no such places in Egypt, partly also for want of water and shade. The ploughed and the fallow land, the banks and hedges, the river and the bed of the inundation canals alone remain. Here a certain number of plants are found, but they are isolated, they never cover a plot of ground, even the grasses, of which there are a good many varieties, never form a green sward; there are no meadows such as charm the eye in other countries, though the clover fields which serve for pasture, and the grainfields as long as they are green, compensate to some extent."

Even the streams, the numerous watercourses and canals, are poorer in vegetation than one would expect under this southern sky. In prehistoric times, the banks of the Nile were covered by primaeval forests, the river changed its bed from time to time, leaving behind stagnant branches; the surface of the water was covered with luxuriant weeds, the gigantic papyrus rushes made an impenetrable undergrowth, until the stream broke through them and carried them as a floating island to another spot. These swamps and forests, inhabited by the crocodile, buffalo, and hippopotamus, have been changed into peaceful fields, not so much by an alteration in the climate, as by the hand of man working for thousands of years. The land has been cleared by the inhabitants, each foot has been won with difficulty from the swamp, until at last the wild plants and the mighty animals which possessed the country have been completely exterminated. The hippopotamus is not to be seen south of Nubia, and the papyrus reeds are first met with in the 9th degree of latitude.

In the first historical period, 3000-2500 B.C., this clearing of the land had been in part accomplished. The forests had long ago disappeared and the acacias of Nubia had to furnish the wood for boat-building; the papyrus, however, was still abundant. The “backwaters,'' in which these rushes grew, were the favorite resorts for sport, and the reed itself was used in all kinds of useful ways. The same state of things existed in the time of Herodotus. In the time of which we shall treat, Egypt was not so over-cultivated as now, though the buildings were no less extensive.

Different plants were characteristic of each part of the country: the papyrus grew thickly in the Delta, the flowering rush in Upper Egypt; and these two plants were used for armorial bearings: a flowering rush for Upper Egypt, and a papyrus plant for the Lower Country. The flowers of these two plants became emblematic of the north and south, and in decorative representations the captives of the north were bound with a rope ending in the blossom of a papyrus, those of the south with one whose end was formed of the flowering rush.

Disasters and in Ancient Egypt

According to scholar Karl Butzer, during floods there was "famine, poverty, mass burials, rotting corpses, suicide, cannibalism, anarchy, mass dislocations, civil war, mass plundering, roving bands of marauders, looting of cemeteries.”

The floods were unpredictable. One that were too high destroyed crops and flooded settlements. Ones that were too low resulted in famine. The Egyptian described disasters as chaos.

The were reports of cannibalism in ancient China, India and Egypt associated with exotic dishes enjoyed by the aristocracy and people surviving during famines.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024