Home | Category: Themes, Early History, Archaeology

EARLY ANCIENT EGYPT

Tadrart Acacus, Libya In the Paleolithic Egypt, the Sahara and the Nile River valleys were much different than they are today. The Sahara was not a desert but was a savannah grasslands with enough vegetation and food to support animals that we associate with the Serengeti . This period of ample vegetation and rainfall lasted until several millennia ago. Then the climate began to dry up and the savannah turned to desert and abundant food supplies disappeared. At that time people that lived in the Sahara began migrating to the Nile Valley, where water, animals and arable were plentiful. This period also coincided with a shift from hunting and gathering to early agriculture and is believed to have been much more temperate and rainy than the Nile Valley is today. [Source: Mitch Oachs and Nathan Bailey, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com, 2002]

Prehistoric Era

Lower Paleolithic Age (250,000-90,000 B.C.)

Middle Paleolithic Age (90,000-30,000 B.C.

Late Paleolithic Age (30,000-7000 B.C.)

Neolithic Age (7000-4800 B.C.)

Predynastic Period (4800-3050 B.C.)

The earliest evidence of war comes from a grave in the Nile Valley in Sudan. Discovered in the mid-1960s and dated to be between 12,000 and 14,000 years old, the grave contains 58 skeletons, 24 of which were found near projectiles regarded as weapons. The victims died at a time the Nile was flooding, causing a severe ecological crisis. The site, known as Site 117, is located at Jebel Sahaba in Sudan. The victims included men, women and children who died violently. Some were found with spear points in near the head and chest that strongly suggest they were not offering but weapons used to kill the victims. There is also evidence of clubbing---crushed bones an the like. Since there were so many bodies, one archaeologist surmised, "It looks like organized, systematic warfare." [Source: History of Warfare by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

See Bronze Age, Early Man (Warfare, Sahara Paintings), Arab History

Book: Midant-Reynes, Béatrix, “The Prehistory of Egypt from the First Egyptians to the First Pharaohs.” Oxford: Blackwell, 2000

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Before the Pharaohs: Exploring the Archaeology of Stone Age Egypt” by Julian Heath (2021) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Egypt, Socioeconomic Transformations in North-east Africa from the Last Glacial Maximum to the Neolithic, 24.000 to 4.000 BC by G. J. Tassie (2014) Amazon.com;

“A Late Paleolithic Kill-Butchery-Camp in Upper Egypt” by Fred Wendorf (1997) Amazon.com;

“Egypt During the Last Interglacial: The Middle Paleolithic of Bir Tarfawi and Bir Sahara East” by Angela E. Close, Romuald Schild, et al. (1993) Amazon.com;

“The Middle and Upper Paleolithic Archeology of the Levant and Beyond by Yoshihiro Nishiaki, Takeru Akazawa, Editors Amazon.com;

” Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East: A Guide” by John J. Shea Amazon.com;

“More than Meets the Eye: Studies on Upper Palaeolithic Diversity in the Near East”

by A. Nigel Goring-Morris, Anna Belfer-Cohen (2017) Amazon.com;

“Transitions Before the Transition: Evolution and Stability in the Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age” by Erella Hovers, Steven Kuhn (2006) Amazon.com;

“Neanderthals in the Levant: Behavioural Organization and the Beginnings of Human Modernity” by Donald O. Henry Amazon.com;

“Climate Change in the Middle East and North Africa: 15,000 Years of Crises, Setbacks, and Adaptation” by William R. Thompson and Leila Zakhirova (2021) Amazon.com;

“When the Sahara Was Green: How Our Greatest Desert Came to Be” by Martin Williams Amazon.com;

“The Green Sahara: Climate Change, Hydrologic History and Human Occupation”

by Ronald G. Blom (2009) Amazon.com;

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“Out of Africa I: The First Hominin Colonization of Eurasia” by John G Fleagle, John J. Shea, Editors (2010), Amazon.com;

“Homo Sapiens Rediscovered: The Scientific Revolution Rewriting Our Origins” by Paul Pettitt Amazon.com;

“The Real Eve: Modern Man's Journey Out of Africa” by Stephen Oppenheimer (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com; Wilkinson is a fellow of Clare College at Cambridge University;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

Green Sahara

Egypt's climate was much wetter in prehistoric times than it is today, and some areas that are now barren desert were green and relatively wet. One famous archaeological site that illustrates this is the "Cave of Swimmers" on the Gilf Kebir plateau in southwestern Egypt. The area is desert now, but thousands of years ago, it was wetter and figures in "Cave of Swimmers" appears to be people swimming, according to the British Museum. This rock art dates back between 6,000 and 9,000 years ago. The wetter period ended around 5,000 years ago, and since then, the deserts of Egypt have remained pretty similar to those that exist now, Marilyn Milton Simpson, a professor of classics at Yale University, told Live Science. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, October 6, 2022]

Tadrart Acacus, Libya

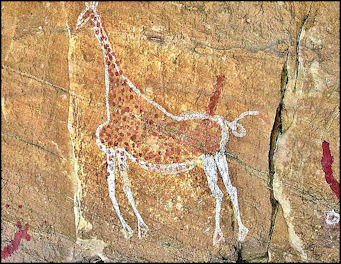

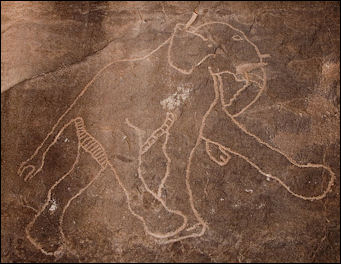

Other Extraordinary images of animals and people from a time when the Sahara was greener and more like a savannah have been left behind. Engravings of hippos and crocodiles are offered as evidence of a wetter climate. Most of the Saharan rock is found in Algeria, Libya, Morocco and Niger and to a lesser extent Egypt, Sudan, Tunisia and some of the Sahel countries. Particularly rich areas include the Air mountains in Niger, the Tassili-n-Ajjer plateau in southeastern Algeria, and the Fezzan region of southwest Libya. Some of the art found in the Sahara region is strikingly similar to rock art found in southern Africa. Scholars debate whether it has links to European prehistoric cave art or is independent of that. [Source: David Coulson, National Geographic, June 1999; Henri Lhote, National Geographic, August 1987]

During the last 300,000 years there have been major periods of alternating wet and dry climates in the Sahara which in many cases were linked to the Ice Age eras when huge glaciers covered much of Europe and North America. Wet periods in the Sahara often occurred when the ice ages were waning. The last major rainy period in the Sahara lasted from about 12,000, when the last Ice Age began to wan in Europe, to 5,000 years ago. Temperatures and rainfall peaked around 9,000 years ago during the so-called Holocene Optimum.

See Separate Article: CLIMATE CHANGE IN ANCIENT EGYPT: GREEN SAHARA, DROUGHT, EMPIRE COLLAPSE? africame.factsanddetails.com

Earliest Hominids in Egypt

When exactly early hominids first arrived in Egypt is not known. The earliest migration of hominids out of Africa took place almost 2 million years ago, with modern humans dispersing out of Africa about 100,000 years ago. Egypt may have been used to reach Asia in some of these migrations. The "oldest known human presence in the Nile Valley [is] estimated to be some 400,000 years ago," Pierre Vermeersch, a professor emeritus of geography at Catholic University of Leuven (KU Leuven) in Belgium, wrote in the book "Palaeolithic Living Sites in Upper and Middle Egypt" (Leuven University Press, 2000). [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

Thomas Hikade of the University of British Columbia wrote: “Evidence for anatomically modern humans exists for approximately 200,000 years, yet stone tools of a much older age have been found in Africa, Europe, and Asia. These stone tools were made by our ancestors, such as homo habilis or homo erectus. It is with the latter that we can associate the finds from the Lower Palaeolithic (700,000-175,000 B.C.) in Egypt, a time when the climate was semi-arid with savannahs and annual rainfalls of about 250- 500 mm. Yet, so far, none of the tools have actually been found in association with bones of homo erectus.” [Source: Thomas Hikade, University of British Columbia, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Mitch Oachs and Nathan Bailey wrote: “The earliest evidence for humans in Egypt dates from around 500,000-700,000 years ago. These hominid finds are those of Homo erectus. Early Paleolithic sites are most often found near now dried-up springs or lakes or in areas where materials to make stone tools are plentiful. One of these sites is Arkin 8, discovered by Polish archaeologist Waldemar Chmielewski near Wadi Halfa. These are some of the oldest buildings in the world ever found. The remains of the structures are oval depressions about 30 centimeters deep and 2 x 1 meters across. Many are lined with flat sandstone slabs. They are called tent rings, because the rocks support a dome-like shelter of skins or brush. This type of dwelling provides a permanent place to live, but if necessary, can be taken down easily and moved. It is a type of structure favored by nomadic tribes making the transition from hunter-gatherer to semi-permanent settlement all over the world. [Source: Mitch Oachs and Nathan Bailey, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com, 2002 +]

Oldest Evidence of Modern Humans in Egypt

The “earliest evidence of modern humans in Egypt dates to 50,000–80,000 years before present — a skeleton of 8- to 10-year-old child discovered at Taramasa Hill in the Nile Valley of southern Egypt in 1994. According to Discover magazine: When humans left Africa to spread out across the world they probably passed through the Nile Valley of Egypt. No skeletons from this time have been found in the area, however, leaving researchers at a loss as to how humans in this important gateway region compared with those in southwestern Asia and in eastern and southern Africa. In 1998, a Belgian archeological team reported that they has found the skeleton of a child in southern Egypt that may be as much as 80,000 years old. The site may well be Africa's oldest intentional burial. [Source Discover November 1, 1998; Wikipedia ]

Pierre Vermeersch from the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium and his colleagues discovered the skeleton at Taramsa Hill. For hundreds of thousands of years, humans and more ancient hominids visited Taramsa to make stone tools, and Vermeersch had been tracking the progress of this industry. People apparently never settled at Taramsa Hill — they merely trekked through on a regular basis, so Vermeersch wasn't expecting to find any human remains. But while excavating a few years ago, he says, "one of our trenches collapsed. And it was in that collapsed trench that by chance we found traces of a skull."

Vermeersch eventually uncovered nearly the entire skeleton of a child resting in a corner of a shallow pit. The child appears to have been carefully positioned. It was seated, facing east, leaning backward, with its head facing up to the sky. Though many stone tools were found near the body, none can be clearly associated with the burial. "We are in a place where they made hundreds of thousands of tools," says Vermeersch, "so everywhere, everything is full of artifacts."

The child was eight to ten years old at death, and Vermeersch isn't sure why he or she died so young. The slender bones and rounded forehead are clearly those of a modern human. The teeth and skull also resemble those of equally old human remains in both East Africa and the Middle East and suggest a connection, Vermeersch says, between these two populations. He plans to move the skeleton to the British Museum for conservation and further study.

30,000-Year-Old Man from the Nile Valley

In 1980, archaeologists unearthed the skeletal remains of a man at Nazlet Khater 2, an archaeological site in Egypt's Nile Valley. Anthropological analysis revealed that the man was between 17 and 29 years old when he died, was approximately 160 centimeters (5 feet, 3 inches) tall and was of African ancestry. He was buried alongside a stone ax. The skeleton is one of the oldest examples of modern humans (Homo sapiens) in Egypt, according to a study published March 22, 2023. [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, April 4, 2023

Live Science reported: In 2023, a team of Brazilian researchers created a facial approximation of the man using dozens of digital images they collected while viewing his skeletal remains, which are part of the collection at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo."The skeleton has most of the bones preserved, although there have been some losses, such as the absence of ribs, hands, [the] middle-inferior part of the right tibia [shin bone] and [the] lower part of the left tibia, as well as the feet," first author Moacir Elias Santos, an archaeologist with the Ciro Flamarion Cardoso Archaeology Museum in Brazil, told Live Science. "But the main structure for facial approximation, the skull, was well preserved."

One characteristic of the skull that stood out to the researchers was the jaw and how it differed from more modern mandibles. A portion of the skull was also missing, but the team copied and mirrored it using the opposite side of the skull and used data points from computerized tomography (CT) scans from living virtual donors."The skull, in general terms, has a modern structure, but part of it has archaic elements, such as the jaw, which is much more robust than that of modern men," study co-researcher Cícero Moraes, a Brazilian graphics expert, told Live Science. "When I observed the skull for the first time, I was impressed with that structure and at the same time curious to know how it would look after approaching the face."

By digitally stitching together the images in a process known as photogrammetry, the researchers created two virtual 3D models of the man. The first was a black-and-white image with his eyes closed in a neutral state, and the second was a more artistic approach featuring a young man with tousled dark hair and a trimmed beard.

Paleolithc Tools in Egypt

Khormusan tools

By the Middle Paleolithic, Homo erectus had been replaced by Homo neanderthalensis, in Europe and the Middle East anyway. Mitch Oachs and Nathan Bailey wrote: “It was about this time that more efficient stone tools were being made by making several stone tools from one core, resulting in numerous thin, sharp flakes that required minimal reshaping to make what was desired. The standardization of stone toolmaking led to the development of several new tools. They developed the lancelet spear point, a better piercing point which easily fit into a wooden shaft. [Source: Mitch Oachs and Nathan Bailey, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com, 2002 +]

“The next advancement in tool making came during the Aterian Industry which dates around 40,000 B.C. The Aterian Industry improved spear and projectile points by adding a notch on the bottom of the stone point, so it could be more securely fastened to the wooden shaft. The other breakthrough in this period is the invention of the spear-thrower, which allowed for more striking power and better accuracy. The spear-thrower consisted of a wooden shaft with a notch on one end where the spear rested. The development of the spear-thrower allowed for increased efficiency in hunting large animals. They hunted a wide variety of animals such as the white rhinoceros, camel, gazelles, warthogs, ostriches, and various types of antelopes. +\

“The Khormusan Industry, which overlapped the Aterian Industry, started some time between 40,000 and 30,000 B.C. The Khormusan Industry pushed advancement even farther by making tools from animal bones and ground hematite, but they also used a wide variety of stone tools. The main feature that marks the Khormusan Industry is their small arrow heads that resemble those of Native Americans. The use of bows by the Aterian and Khormusan industries is still questioned; to date there is no set proof that they used bow technology.” +\

Hikade wrote: “ In ancient Egypt, flint or chert was used for knapped stone tools from the Lower Palaeolithic down to the Pharaonic Period. The raw material was available in abundance on the desert surface, or it could be mined from the limestone formations along the Nile Valley. While the earliest lithic industries of Prehistoric Egypt resemble the stone tool assemblages from other parts of Africa, as well as Asia and Europe, the later Prehistoric stone industries in Egypt had very specific characteristics, producing some of the finest knapped stone tools ever manufactured in the ancient world. Throughout Egypt’s history, butchering tools, such as knives and scrapers, and harvesting tools in the form of sickle blades made of flint, underlined the importance of stone tools for the agrarian society of ancient Egypt.”

Lower Palaeolithic (700,000-175,000 B.C.) Egypt

Nubian tools

Thomas Hikade of the University of British Columbia wrote: “The Lower Palaeolithic starts with the appearance of the Acheulean industry, named after the site Saint-Acheul in France, which is rarely found in datable contexts in Egypt. Finds of this period were discovered in Western Thebes in Upper Egypt in the 19th century, while finds from Lower Egypt come from Abbasiya, near Cairo. A first attempt to summarize the Old Stone Age in Egypt was made by Jacques de Morgan (1897), and surveys along the Nile Valley in Nubia and Egypt, as well as in the Fayum oasis, aimed to document and associate the geology of Egypt with its prehistory. In the early 1930s, excavations were undertaken in the Fayum oasis, whence Palaeolithic artifacts were already known. [Source: Thomas Hikade, University of British Columbia, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The Kharga Upper Acheulean industry was later described as having produced very well-made handaxes with some simple Clactonian choppers. Further south in the Western Desert, at sites such as Bir Tarfawi and Bir Sahara, late Acheulean lakes allowed humans to exploit aquatic resources . A recent study concentrating on the site of Nag Ahmed el-Khalifa, south of Abydos, which dates to 400,000-300,000 BP, found that the people there fully focused on handaxes as their main tool type, most being of cordiform shape. Handaxes were indeed the main tool type of the Lower Palaeolithic. Homo erectus removed flakes from a nodule on the ventral and the dorsal surface with a direct hammer stone technique, giving the tool an amygdaloid, subtriangular, lanceolate, or cordiform shape with converging edges. The multi-functional ax would have satisfied various needs, such as crushing bones, skinning mammals, scraping hides, etc. — in short, butchering found carcasses or hunted game and, when needed, it could be used as a weapon. It remains surprising that the handax was so long-lasting and dominated flint tools for several hundreds of thousands of years. One reason for this conservatism may have been the inability of early humans to fully integrate knapping skills and toolkits with knowledge of the environment.

Middle Palaeolithic (175,000-40,000 B.C.) Egypt

The Middle Palaeolithic (175,000-40,000 B.C.) saw the appearance of modern humans in Africa and some human remains have been found associated with Middle Palaeolithic material . This time period is essentially characterized by a higher stone tool variety in comparison with the Lower Palaeolithic, which also reflects cultural diversity. The lithic industries of the Middle Palaeolithic are also known as Mousterian, after the type site of Le Moustier, a rock shelter in the Dordogne in southwestern France. The Mousterian is characterized by its special core reduction strategy (“Levallois technique”). Using a hard hammer technique, this technique provided control over the size and shape of the final flake. The method also allowed for the production of projectile points, the so-called “Levallois points”. A variant in Egypt and Sudan was the Nubian Levallois point. Levallois points could be attached to a wooden shaft as sharpened spear heads. The instrument could be used as a thrusting weapon, but also could be thrown at prey, thus reducing the risk of injury during the hunt and enabling the hunting of animals previously out of range. [Source: Thomas Hikade, University of British Columbia, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Middle Paleolithic tools

“Middle Palaeolithic scrapers are particularly varied, whether due to different tool industries made by different people or to varying seasonal activities at different sites. It is also possible that the basic shape and size of scrapers was originally more or less the same, and that many scraper types in fact represent different stages in a changing reduction continuum from blank to discarded tool.

“Middle Palaeolithic lithic industries in Egypt share some features with the overall picture in North Africa, Europe, and Asia, especially the clear shift away from a bifacial core industry towards a flake/blade industry. Due to the lack of deeply stratified sites, the archaeological record of the Middle Palaeolithic still shows wide chronological gaps from site to site, which makes it difficult to paint a homogeneous picture of the period in Egypt. A few elements are specific to North Africa, like the tanged point for socket- hafting of the Aterian, a Levallois-based industry originally named after Bir el-Ater in Algeria and widespread across the Maghreb, the Sahara, and even south into Niger. A late Middle Palaeolithic industry of the southern Nile Valley is known from Khor Musa near the Second Cataract. It is a well-defined Levallois-based flake-industry in which denticulates and well-made burins played a major role, usually for specific work on bones or wood.

“Many of the Middle Palaeolithic sites so far investigated in the Nile Valley are related to the exploitation of chert in the form of cobbles. One such site is Nazlet Khater 4, c. 30 kilometers northwest of Sohag in Middle Egypt. Nazlet Khater is thus far the oldest subterranean mining site in the world, with many extraction ditches, shafts, and galleries. While finds of human remains and artifacts of the Palaeolithic are very rare, it is from the very late Middle Palaeolithic that we have the first burial of a modern human in Egypt. Near Dendara in Middle Egypt, and in an area of chert mining activity, a child was buried about 55,000 years ago. A long-used Middle Palaeolithic site with a fireplace with the burnt bones of buffalo and gazelle, as well as catfish and shell, is known from Sodmein Cave in the Eastern Desert.

Prehistoric Stone Tool Workshops Found in the Egyptian Desert

According to a study published March 27, 2024 in the peer-reviewed journal Antiquity, researchers found stone-tool “work shops” at an inland desert area known as Wadi Abu Subeira during an archaeological survey in 2022. During their survey, archaeologists located dozens of artifacts and sites from the Stone Age. Previous archaeologists had found traces of prehistoric life in the area. Wadi Abu Subeira is a desert region near Aswan, a city about 600 miles south of Cairo. [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, April 4, 2024]

Archaeologists found five Stone Age workshops where different types of rock were shaped into tools, the study said. These include a rectangular stone cleaver and large teardrop-shaped handax, with chip marks around its edge. One prehistoric workshop was located on an outcropping of sandstone. Archaeologists found “large flakes” left from working the stones, “several handaxes” and some partially made tools. At another workshop site, archaeologists found rock cores, points and other flakes left from the knapping process. Photos show the stone artifacts scattered around the ancient site.

Archaeologists attributed all the finds to the Earlier or Middle Stone Age but did not specify an exact age. The Middle Stone Age is a loosely defined prehistoric period, according to Oxford Research Encyclopedia. The period began roughly 300,000 years ago and continued until about 20,000 years ago. Taken together, archaeologists said “the workshops likely represent repeated episodes of exploitation of the outcrops over a long timespan” and show how ancient humans had “well-developed knowledge of the environment in this part of the desert. ”

Migration from the Sahara to the Nile Beginning 30,000 Years Ago

Mitch Oachs and Nathan Bailey wrote: ““During the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic around 30,000 B.C., the pluvial conditions ended and desertification overtook the Sahara region. People were forced to migrate closer to the Nile River valley. Near the Nile, new cultures and industries started to develop. These new industries had many new trends in their production of stone tools, especially that of the miniaturization and specialization. [Source: Mitch Oachs and Nathan Bailey, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com, 2002 +]

“The Sebilian Industry that followed the Khotmusan Industry added little advancement to tool making, and some aspects even went backwards in tool making. The Sebilian Industry is known for their development of burins, small stubby points. They started by making tools from diorite, a hard igneous rock which was widely found in their environment. Later on they switched over to flint which was easier to work. +\

“The Sebilian Industry did coexist with another culture called the Silsillian Industry which did make significant advancements in tool technology. The Silsillians used such blades as truncated blades and microliths. The truncated blades are made for one specific task and are of irregular shape. The microliths are small blades used in such tools as arrows, sickles, and harpoons. The micro blade technology was most likely used because of the small supply of good toolmaking stone, such as diorite and flint. +\

“The Qadan Industry was the first to show major signs of intensive seed collection and other agriculturally similar techniques. They used such tools as sickles and grinding stones. These tools show that by this time people had developed the skills for plant-dependent activities. The use of these tools astonishingly vanished around 10,000 B.C. for a small period of time, perhaps as a result of climatic change. This resulted in hunting and gathering returning as the adaptive strategy. +\

“Beginning after 13,000 B.C., cemeteries and evidence of ritual burial are found. Skeletons were often decorated with necklaces, pendants, breast ornaments and headdresses of shell and bone. The Epipaleolithic Period dates between 10,000-5,500 B.C. and is the transition between the Paleolithic and the Predynastic periods in ancient Egypt. During this time, the hunter-gatherers began a transition to the village-dwelling farming cultures. +\

“The Nile Valley of the Paleolithic was much larger then it is today, its annual flooding made permanent habitation of its floodplain impossible. As the climate became drier and the extent of the flooding was reduced, people were able to settle on the Nile floodplain. After 7000 B.C., permanent settlements were located on the floodplain of the Nile. These began as seasonal camps but become more permanent as people began to develop true agriculture.” +\

Wadi Kubbaniya (17,000–15,000 B.C.): Earliest Evidence of Advanced People in Egypt?

Wadi Kubabyia skeleton

Diana Craig Patch and Laura Anne Tedesco of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “In Egypt, the earliest evidence of humans can be recognized only from tools found scattered over an ancient surface, sometimes with hearths nearby. In Wadi Kubbaniya, a dried-up streambed cutting through the Western Desert to the floodplain northwest of Aswan in Upper Egypt, some interesting sites of the kind described above have been recorded. A cluster of Late Paleolithic camps was located in two different topographic zones: on the tops of dunes and the floor of the wadi (streambed) where it enters the valley. [Source: Diana Craig Patch, Department of Egyptian Art and Laura Anne Tedesco Department of Education, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Although no signs of houses were found, diverse and sophisticated stone implements for hunting, fishing, and collecting and processing plants were discovered around hearths. Most tools were bladelets made from a local stone called chert that is widely used in tool fabrication. The bones of wild cattle, hartebeest, many types of fish and birds, as well as the occasional hippopotamus have been identified in the occupation layers. Charred remains of plants that the inhabitants consumed, especially tubers, have also been found. \^/

“It appears from the zoological and botanical remains at the various sites in this wadi that the two environmental zones were exploited at different times. We know that the dune sites were occupied when the Nile River flooded the wadi because large numbers of fish and migratory bird bones were found at this location. When the water receded, people then moved down onto the silt left behind on the wadi floor and the floodplain, probably following large animals that looked for water there in the dry season. Paleolithic peoples lived at Wadi Kubbaniya for about 2,000 years, exploiting the different environments as the seasons changed. Other ancient camps have been discovered along the Nile from Sudan to the Mediterranean, yielding similar tools and food remains. These sites demonstrate that the early inhabitants of the Nile valley and its nearby deserts had learned how to exploit local environments, developing economic strategies that were maintained in later cultural traditions of pharaonic Egypt.” \^/

Late Palaeolithic (40,000-7000 B.C.) Stone Tools in Egypt

Thomas Hikade of the University of British Columbia wrote: “Due to the lack of a lithic sequence from the Middle to the Upper Palaeolithic, the transition to and the development of the material culture of the Upper Palaeolithic (40,000-35,000 B.C.) in the Western Desert and the Nile Valley is still not well understood. Finds from the Dahkla oasis give evidence that the Western Desert was apparently not depopulated and no occupational hiatus existed during that time. One of the very few Upper Palaeolithic sites known from the Nile Valley is the already-mentioned mining site at Nazlet Khater 4 in Middle Egypt. Altogether, the material remains of the Upper Palaeolithic are very scarce in Egypt. [Source: Thomas Hikade, University of British Columbia, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“With climate change in the Final Palaeolithic in Egypt (25,000-7000 B.C.), aquatic resources were increasingly exploited. Large mammals still complemented the diet, but fish, especially catfish (Clarias), clearly became one of the main staples, along with wetland tubers, particularly nut-grass tubers. Microlithic bladelet tools became common in most parts of Northern Africa . Backed bladelet tools are so standardized, non- varying, and consistent in their forms that it is assumed that they were made and used in face-to-face social contexts, playing a significant role in the social identity of the people who manipulated them. Small backed bladeletes, lunates, and triangulates were possibly used as part of composite pieces of equipment like harpoons or spears. With this new industry, a dramatic increase in the produced cutting edge of flint can be observed. For hundreds of thousands of years, the cutting edge gained from 1 kilogramof raw material remained under 10 m, but the amount of cutting edge now climbed to almost 100 m.

“The most important site for this period lies at Wadi Kubbaniya north of Aswan, with almost 30 locales of the Late Palaeolithic. The sites lie on sand dunes on the plains in front of the dunes, and on high areas near the mouth of the wadi. The chronological sequence between 25,000 and 11,000 BP shows a rather rapid change of material culture with different strategies of sustenance, all competing for the resources along the Nile Valley. This competition was due to high floods during the Holocene wet phase (12,000-8500 BP) in the valley, which were followed by a hyper-arid climate that also limited the living and exploitation space in the alluvial plain. This struggle for resources and the consequences of violent conflicts are well attested by the Wadi Kubbaniya skeleton of a man in his early twenties who was speared from behind, and by the dozens of people who were killed and buried at Jebel Sahaba.

Rock Art in Egypt

Dirk Huyge of the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels, Belgium wrote: “Rock art, basically being non-utilitarian, non-textual anthropic markings on natural rock surfaces, was an extremely widespread graphical practice in ancient Egypt. While the apogee of the tradition was definitely the Predynastic Period (mainly fourth millennium B.C.), examples date from the late Palaeolithic (c. 15,000 B.C.) until the Islamic era. Geographically speaking, “Egyptian” rock art is known from many hundreds of sites along the margins of the Upper Egyptian and Nubian Nile Valley and in the desert hinterlands to the east and west. Despite clear regional discrepancies, most of this rock art displays a great deal of shared subject matter, such as the profusion of boat figures, supposedly attesting to the existence of a more or less uniform “spiritual culture” throughout the above-defined area. Furthermore, its intimate iconographical relationship to the archaeologically known Egyptian cultures, both in a synchronic and a diachronic perspective, allows for some solid reasoning regarding the raison d’être of this graphic tradition. Without excluding other possible meanings and motivations, it seems that the greater part of the rock art closely reflects the religious and ideological concerns of its makers. [Source: Dirk Huyge, Royal Museums of Art and History, Brussels, Belgium, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“In this brief and necessarily selective overview of Egyptian rock art research, the “Bedouin-oriented” petroglyphs from the westernmost part of the Negev Desert and Sinai Peninsula will not be discussed. This art, characterized essentially by ibex-hunting and camel-riding scenes, belongs to the Egyptian rock art domain from a geopolitical viewpoint only. Similarly, the vast “pastoral” pictorial complexes of the Gilf Kebir and Gebel el-Uweinat (near or on the Egypt-Libya-Sudan border) will not be considered. This rock art, in fact, refers much more to the central Saharan artistic repertoire (Round Head and Bovidian schools/periods in particular) than to the Nilotic, and is also quite distinct from anything that has thus far been found in the oases of the Western Desert.

Libyan Cave Art

“Egyptian rock art, as considered here, is therefore limited to the southern Egyptian and northern Sudanese (Nubian) Nile Valley, the Eastern (Red Sea) Desert, and parts of the Western (Libyan) Desert, including most of the oases. Apart from the numerous technical and stylistic similarities, the rock art within this area displays a great deal of shared subject matter, perhaps the most striking of which is the profusion of boat representations. It may therefore be postulated that this rock art reflects a more or less uniform “spiritual culture”—a cognitive consensus or communal sphere of ideas in which communication through rock art (the collective use of certain intellectual concepts and structures) was possible and stimulated by society as a whole. This vast rock art repertoire can moreover be intimately linked with the local, archaeologically known cultures. These cultures, both prehistoric and historic, are characterized by an overwhelmingly rich iconography. That the latter have often been found in well-documented archaeological contexts holds great potential, not only with regard to dating and culture-historical attribution of the rock art, but also with regard to interpretation (meaning and motivation).

See Separate Article: ROCK ART FROM PREHISTORIC EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Middle Paleolithoc tools from pharonic civilization, Nubian tools from Plos and Khormusan tools from Science Digest, el-Hosh rock art, Per Storemyr Archaeology & Conservation.

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024