Home | Category: Themes, Early History, Archaeology

ANCIENT ROCK ART IN EGYPT

Egypt's climate was much wetter in prehistoric times than it is today, and some areas that are now barren desert were green and relatively wet. One famous archaeological site that illustrates this is the "Cave of Swimmers" on the Gilf Kebir plateau in southwestern Egypt. According to Live Science: Today, the area is very arid, but thousands of years ago, it was moister, and some of the rock art found in caves in the area appears to show people swimming, according to the British Museum. This rock art dates back between 6,000 and 9,000 years ago.The wetter period ended around 5,000 years ago, and since then, the deserts of Egypt have remained pretty similar to how they are now, Joseph Manning, the William K. and Marilyn Milton Simpson professor of classics at Yale University, told Live Science. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, October 6, 2022]

As the Sahara region dried out grasslands and lakes disappeared. Desiccation occurred relatively quickly, over a few hundred years. Desertification processes were accelerated as vegetation, which helped generate rain, was lost, causing even less rain, and the soil lost its ability to hold moisture when it did rain. Light-colored land without plants reflects rather than absorbs sunlight, producing less warm, moist cloud-forming updrafts, causing even less rain. When it did rain the water washed away or evaporated quickly. The result: desert.

By 2000 B.C. the Sahara was as dry as it is now. The last lake dried up around 1000 B.C. The people that lived in the region were forced to leave and migrate south to find food and water. Some scientist believe some of these people settled on the Nile and became the ancient Egyptians.

Dirk Huyge of the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels, Belgium wrote: “Rock art, basically being non-utilitarian, non-textual anthropic markings on natural rock surfaces, was an extremely widespread graphical practice in ancient Egypt. While the apogee of the tradition was definitely the Predynastic Period (mainly fourth millennium B.C.), examples date from the late Palaeolithic (c. 15,000 B.C.) until the Islamic era. Geographically speaking, “Egyptian” rock art is known from many hundreds of sites along the margins of the Upper Egyptian and Nubian Nile Valley and in the desert hinterlands to the east and west. Despite clear regional discrepancies, most of this rock art displays a great deal of shared subject matter, such as the profusion of boat figures, supposedly attesting to the existence of a more or less uniform “spiritual culture” throughout the above-defined area. Without excluding other possible meanings and motivations, it seems that the greater part of the rock art closely reflects the religious and ideological concerns of its makers. [Source: Dirk Huyge, Royal Museums of Art and History, Brussels, Belgium, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

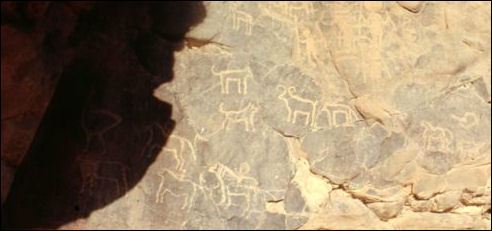

The “Bedouin-oriented” petroglyphs from the westernmost part of the Negev Desert and Sinai Peninsula are characterized essentially by ibex-hunting and camel-riding scenes. This belongs to the Egyptian rock art domain from a geopolitical viewpoint only. Similarly, the vast “pastoral” pictorial complexes of the Gilf Kebir and Gebel el-Uweinat (near or on the Egypt-Libya-Sudan border) refers much more to the central Saharan artistic repertoire (Round Head and Bovidian schools/periods in particular) than to the Nilotic, and is also quite distinct from anything that has thus far been found in the oases of the Western Desert.

“Egyptian rock art, as considered here, is therefore limited to the southern Egyptian and northern Sudanese (Nubian) Nile Valley, the Eastern (Red Sea) Desert, and parts of the Western (Libyan) Desert, including most of the oases. Apart from the numerous technical and stylistic similarities, the rock art within this area displays a great deal of shared subject matter, perhaps the most striking of which is the profusion of boat representations. It may therefore be postulated that this rock art reflects a more or less uniform “spiritual culture”—a cognitive consensus or communal sphere of ideas in which communication through rock art (the collective use of certain intellectual concepts and structures) was possible and stimulated by society as a whole. This vast rock art repertoire can moreover be intimately linked with the local, archaeologically known cultures. These cultures, both prehistoric and historic, are characterized by an overwhelmingly rich iconography. That the latter have often been found in well-documented archaeological contexts holds great potential, not only with regard to dating and culture-historical attribution of the rock art, but also with regard to interpretation (meaning and motivation).

See Separate Article: SAHARAN ROCK ART factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Rock Art of the Eastern Desert of Egypt: Content, Comparisons, Dating and Significance” (BAR International) by Tony Judd (2009) Amazon.com;

Desert Boats. Predynastic and Pharaonic era Rock-Art in Egypt’s Central Eastern Desert: Distribution, dating and interpretation (BAR International Series)

by Francis Lankester (2013) Amazon.com;

“Desert RATS: Rock Art Topographical Survey in Egypt's Eastern Desert” (BAR International) by Maggie Morrow, Mike Morrow, et al. (2010) Amazon.com;

“Graffiti and Rock Inscriptions from Ancient Egypt: A Companion to Secondary Epigraphy” by Chloe Ragazzoli, Khaled Hassan, et al. (2023) Amazon.com;

“Rock Art of the Sahara” by Henri Hugot (2000) Amazon.com;

“Rock Art of the Jebel Uweinat: [Libyan Sahara] (1978) by Francis L. van Noten, Hans Rhotert, Xavier Misonne (1978) Amazon.com;

“Before the Pharaohs: Exploring the Archaeology of Stone Age Egypt” by Julian Heath (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Early Egypt: Social Transformations in North-East Africa, c.10,000 to 2,650 BC” (Cambridge World Archaeology) by David Wengrow (2006) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Egypt, Socioeconomic Transformations in North-east Africa from the Last Glacial Maximum to the Neolithic, 24.000 to 4.000 BC by G. J. Tassie (2014) Amazon.com;

“A Late Paleolithic Kill-Butchery-Camp in Upper Egypt” by Fred Wendorf (1997) Amazon.com;

“Egypt During the Last Interglacial: The Middle Paleolithic of Bir Tarfawi and Bir Sahara East” by Angela E. Close, Romuald Schild, et al. (1993) Amazon.com;

“The Middle and Upper Paleolithic Archeology of the Levant and Beyond by Yoshihiro Nishiaki, Takeru Akazawa, Editors Amazon.com;

” Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East: A Guide” by John J. Shea Amazon.com;

“More than Meets the Eye: Studies on Upper Palaeolithic Diversity in the Near East”

by A. Nigel Goring-Morris, Anna Belfer-Cohen (2017) Amazon.com;

“Transitions Before the Transition: Evolution and Stability in the Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age” by Erella Hovers, Steven Kuhn (2006) Amazon.com;

“Climate Change in the Middle East and North Africa: 15,000 Years of Crises, Setbacks, and Adaptation” by William R. Thompson and Leila Zakhirova (2021) Amazon.com;

“When the Sahara Was Green: How Our Greatest Desert Came to Be” by Martin Williams Amazon.com;

“The Green Sahara: Climate Change, Hydrologic History and Human Occupation”

by Ronald G. Blom (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com; Wilkinson is a fellow of Clare College at Cambridge University;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

Roundhead Period of Saharan Rock Art

Tadrart Acacus Libya The first human figures in Saharan art were depicted around 9,000 ears ago. This marks the beginning of the Round Head period which overlaps with the late Babalus period and the early Pastoral period. Human figures from this period tend to have rounded heads and featureless faces. The figures range in size from a few centimeters to five meters in height.

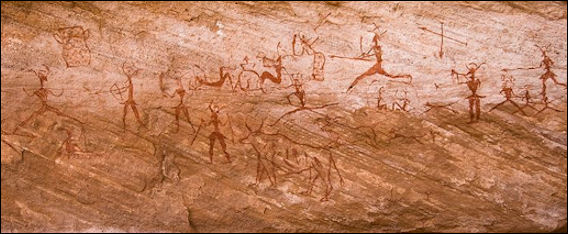

Roundhead Period people are shown standing among cattle, hunting with bows, and dancing with masks on their heads. There are many images of running archers in which the strings of their bows and the leg muscles are visible. Pieces that seem to represent some kind of shamanistic experience depict round-headed people floating towards a figure that seems to be a shaman. There are also scenes of everyday life such as people washing the hair. Images of boats have been found in the Nile Valley and the Red Sea hills.

An 8,000-year-old rock paintings in the Tassil-n-Ajjer in Algeria depicts dancers and musicians. One of the instruments pictured is still played thousands of miles south in the Kalihari. Seven-thousand-year-old cave painting in the Sahara seem to depict bows being used as musical instrument. Bushmen today make haunting music with bow instruments that are placed in the mouth. Sound is produced by tapping a sinew string with a reed.

One painting from Tassili-n-Ajjer dubbed the elephant dance depicts a line of figures connected by a rope or cord. They men wear hip-high white leggings, reminiscent of grass costumes worn in West Africa, and appear to be engaged in some ritual or ceremony.

Pastoral Period of Saharan Rock Art

Around 7,000 years ago domesticated animals began appearing in Saharan rock art. This marked the beginning of the Pastoral Period. The works from this period have a more naturalistic style and depict scenes from everyday life. They are presumed to have been made by herders. The works have more details and appear to express concerns about composition. Rock art specialist Alex Campbell told National Geographic that paintings form this period “started to show man as above nature, rather than as part of nature, seeking its help.”

Images from the Pastoral Period seem to suggest that black people lived in the Sahara at that time. Black people, some of whom wear garments and adornments and have hairdos like some current tribal groups in Africa, are often shown among herds of cattle . Some show men riding n bulls. There are also scenes of couples making love and women carrying children on their backs.

One image from Tassili-n-Ajjer seems to depict help from the spirit world being sought with animal magic. A member of the Fulani tribe that still conduct similar rituals told National Geographic: “The spirit of the earth assumes the shape of the snake goddess, Tyanaba, protector of cattle. Curved lines represent the serpent as she encircles a sacred bull. A man, second from the right joins four women....At the far right, the “mistress of milk” reclines to chant to the earth. She implores that the goddess lift the bulls’ bewitchment — perhaps an illness — and ensure propagation of the herd. The woman third from the left listens for the earth’s response.”

Among the early depictions of war is a battle scene, in a rock painting in Tassili n’Ajjer. dated to between 4300 and 2500 B.C., with groups of men firing bows and arrows at each other. In the image a group on the right stand ready to fire their bows as a group on the left begins an assault.

Horse and Camel Period of Saharan Rock Art

The arrival of the horse in the region around 1650 B.C. inaugurated the Horse period. The arrival of the camel around 200 B.C. inaugurated the Camel period and is seen as indicator that Sahara was drying out and becoming the Sahara as we know it and a desert so dry it could no longer support horses.

Images from the Horse period include hunters in chariots, carrying weapons in one hand and holding reigns in the other hand, being chased by a dog. Some scholars regard these hunters as a the People of the Sea, a mysterious group with bronze weapons and armor that unsuccessfully attacked Egypt before retreating into the desert where they assimilated with the indigenous Garamantes, later described by Herodotus as “very powerful people” who rode four-horse chariots and chased black cave dwellers “like the screeching of bats.”

Many images from the Camel period have a childlike quality. The camels in these images are sometimes ridden by riders who ride on saddles covered by a linen framework called a basour that provided the riders with some sun protection.

Rock Art Sites in Egypt

Dirk Huyge of the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels, Belgium wrote: “The potentialities of Egyptian rock art have been explored at many different locations throughout the above-defined area. One of the places where highly significant discoveries have been made during the past few decades is the Theban Desert immediately northwest of Luxor. In the scope of the Theban Desert Road Survey, John and Deborah Darnell of Yale University have recorded, apart from a wealth of rock inscriptions, an impressive array of early to terminal Predynastic rock art, including depictions of boats, various animals, and superbly detailed human figures. Much of this rock art is closely linked to ancient caravan routes short-cutting the Qena Bend of the Nile and/or leading from the Nile Valley to the oases of the Western Desert. The age of many of these figures is well established. On the basis of close resemblances to depictions on painted ceramics and other decorated artifacts, many date unquestionably to the mid- to late Predynastic Period (Naqada I-II, c. 4000 – 3200 B.C.). Others may even be older and can be attributed to the early Predynastic (Tasian or Badarian, c. 4500 – 4000 B.C.). [Source: Dirk Huyge, Royal Museums of Art and History, Brussels, Belgium, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“These new discoveries complement rock art long known from the Nile Valley proper, such as that from the site of Elkab and from the Eastern Desert. The latter area, already partly explored by Weigall, Winkler, and others in the early part of the previous century, has seen relatively little systematic recording in recent years. However, some surveys, conducted by amateur archaeologists since the late 1990s between the Wadi Hammamat in the north and the Wadi Barramiya in the south, have substantially added to the currently available documentation. One of the most striking features of this Eastern Desert rock art is the preponderance of images of high-prowed boats, more than 240 of which have been logged to date. In this sense and in several other aspects (for instance, a greater emphasis on cattle representations and herding scenes), it is different from the rock art of the Nile Valley. How these regional discrepancies should be explained is still a matter of dispute and speculation. It has been suggested that the Eastern Desert rock art was the work of “proto-Bedouin”—that is, nomads who resided in the desert on a semi- permanent basis, but were in regular contact with Nile Valley dwellers and had an intimate knowledge of the natural and cultural Nilotic environment.

Gravure Rupestre, Algeria

“The suggestion may also apply to the rock art of the Western Desert, the oases in particular, which also has its own particularities as well as many similarities to the rock art of the Nile Valley. One striking feature of Western Desert rock art, that of Dakhla and Kharga Oases in particular, consists of stylized images of sitting or standing obese women dressed in often elaborately decorated long skirts. According to Lech Krzyżaniak (personal communication) the images are certainly pre-Old Kingdom and should be dated to early or mid-Holocene times (eighth to fourth millennium B.C.). As the area of distribution of these figures corresponds to that of the local Neolithic (Bashendi A and B) assemblages, they are possibly associated and may therefore belong to the sixth or fifth millennium B.C.. It is possible that rock art from Farafra Oasis, including cave paintings featuring numerous hand stencils, may be equally old. The bulk of the rock art in the oases of the Western Desert, however, seems to be Pharaonic (dating mostly to the late Old Kingdom) and displays a rather stereotypical repertoire: incised sandals, outlines of feet, hunting scenes, mammals, birds, feathered men, and pubic triangles (see, for instance, Kaper and Willems 2002 for rock art related to late Old Kingdom military installations at Dakhla Oasis). Still later rock art, of the Greco-Roman and Islamic Periods, is known from, among other places, Kharga and Bahriya. Among its representations are geometric signs, equid drawn carts or chariots, and schematic figures of humans and camels.

Oldest Rock Art in Egypt

Dirk Huyge of the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels wrote: “Whereas the bulk of Egyptian petroglyphs can be ascribed to the Predynastic cultures immediately preceding and foreshadowing Pharaonic civilization (mainly fourth millennium B.C.), still older rock art has come to light in recent years. Dating to the very end of the Palaeolithic, the so-called “Epi-palaeolithic” (c. 7000 - 5500 B.C.), are most probably the bizarre-looking mushroom-shaped designs that characterize the rock art of el-Hosh, about 30 kilometers south of Edfu. Frequently appearing in clusters and occasionally as isolated figures, these designs, which can tentatively be interpreted as representations of labyrinth-fish-traps, are often associated with abstract and figurative motifs, including circles, ladder-shaped drawings, human figures, footprints, and crocodiles. Probably affiliated “geometric” rock art assemblages are known from Sudanese Nubia (Abka) and have recently also been reported from the Aswan area . The occurrence of similar rock art at several locations in the Eastern Desert (and possibly also at Dakhla, Farafra, and Siwa in the Western Desert) suggests that the Epi-palaeolithic image- makers were extremely mobile and must have lived a nomadic existence. Rock art examples pre-dating the Epi-palaeolithic have recently been discovered at three locations in the Upper Egyptian Nile Valley: Abu Tanqura. [Source: Dirk Huyge, Royal Museums of Art and History, Brussels, Belgium, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Bahri at el-Hosh, Qurta, and Wadi Abu Subeira. The rock art repertoire at these sites is fundamentally different from the Epi- palaeolithic assemblages and consists for the most part of naturalistically drawn animal figures. Bovids (wild cattle or aurochs) are largely predominant , followed by birds, hippopotamuses, gazelle, fish, and hartebeest. In addition, there are also several highly stylized representations of human figures and a small number of probable non-figurative or abstract signs. For the time being, the dating evidence is entirely circumstantial, but it is likely that this rock art is late Palaeolithic in age. A date of about 15,000 B.C. has tentatively been proposed. If this is correct, this rock art is not only Egypt’s most ancient art, but one of the oldest graphic traditions known to date from the African continent.

El-Hosh geomatric rock art

Why Was Early Rock Art Made in Egypt?

Dirk Huyge wrote: “Setting aside simplistic and naive explanations—for instance, that the rock drawings may be merely the result of casual pastime or the exercises of sculpture- apprentices—magical, totemistic, religious, and politico-ideological motivations have been advanced to explain the ancient Egyptian rock art tradition. None of these clarifies the rock art phenomenon as a whole, but it appears that religion and ideology offer more satisfactory and certainly less circuitous approaches than magic and totemism, both of which are grounded on indirect ethnographical comparisons. Inevitably, both the religious and the ideological approach have been carried to extremes. For instance, Červiček, in various contributions, has attempted to demonstrate that Egyptian rock art is completely permeated with religion: without exception human figures pose in cultic attitudes, carry out liturgical actions, or represent anthropomorphic deities; boats are meant to be divine or funeral barques, and animals relate to offering rituals or represent a zoomorphic pantheon. Ultimately, creating rock art is performing a devotional act in itself. A more cautious and balanced approach may be required. [Source: Dirk Huyge, Royal Museums of Art and History, Brussels, Belgium, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“On a general epistemological level, it may be suggested that any hermeneutic approach to rock art should ideally be conceived as a historical exegesis. This implies that the search for meaning and motivation should basically be founded on contemporaneous materials and sources. With regard to the prehistoric and early historic periods, however, such information is sparse or even non-existent. Non-synchronous sources then have to be sought. To a considerable extent this is also the case for the Egyptian rock art production. Not unlike many other rock art traditions in the world, Egyptian rock art is truly a “fossil” record, in the sense that no living or oral traditions elucidate its contents, meaning, or motivation. Fortunately, from the Predynastic through the Pharaonic Periods, ancient Egyptian civilization displayed a single line of progress and a considerable degree of conceptual conservatism. Pharaonic culture was a gradual outgrowth of indigenous prehistoric traditions. In fact, what occurred in Egypt between c. 3200 and 3030 B.C. (at the time of state formation), was not an abrupt change of iconography but rather a profound formalization, standardization, and officialization. Image-making passed from a less disciplined “pre-formal” artistic stage to a “formal” canonical phase. This change is immense, but, basically, it is cosmetic, with the content of the iconography (the themes) and the underlying beliefs (the meaning and motivation) remaining much the same, as they would for several millennia. With that in mind, a diachronic approach to rock art, in which phenomena are not considered individually but as integral parts of a historical chain of development, can be considered scientifically sound.

“Attempts toward such an approach, applied to the rock art of the Upper Egyptian site of Elkab, suggest that petroglyphs were subject to religious, ideological, and other mental shifts traceable through time in the culture-historical record and correspond to a range of meanings and motivations, such as cosmology, ideology, and personal religious practice, as well as more trivial incentives, such as pride and prestige.

Graffiti in Ancient Egypt as a Historical Source

Eugene Cruz-Uribe of Northern Arizona University wrote: “Some of the earliest evidence for written communication in Egypt derives from figural graffiti—a variation of rock art. These texts are evidenced from many sites in Egypt, especially the Western Desert. From probable derivative of rock art, were a significant means of recording religious, totemic, gender, and territorial boundaries throughout Egypt, the Near East, and Africa. In Egypt, numerous sites with figural graffiti have been found along the Nile Valley and in the Eastern Desert; however, the largest number of sites with collections of prehistoric rock art comes from Nubia and the Western Desert. The locations of these sites coincide with known prehistoric “occupation” and usage areas (such as camp sites, watering holes, and sources of flint). The surveys and excavations by Schild, Wendorf, Mills, Darnell, Klemm, and many others have enriched the corpus of known rock-art sites. The Nubian salvage operations in the Nile Valley—especially those of the Čzech concession and, more recently, of the Belgian team —have reported major sites that have evoked comparisons with the Lascaux galleries in France. [Source: Eugene Cruz-Uribe, Northern Arizona University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“Analysis of the figural graffiti found at these sites has developed slowly. While earlier publications focused mainly on cataloguing and describing the finds, and while figural graffiti that have an accompanying (textual) inscription have often been fronted in discussions, it is important to emphasize that both textual graffiti and figural graffiti are grapholects of the Egyptian communication system as a whole. Representative of figural graffiti are boat drawings, discussed by Červíček, who established criteria with which to place these items within a concise chronological framework. The studies by Huyge have expanded our understanding of these and other types of images. Huyge has suggested that we can analyze certain non-textual graffiti using ethnographic markers and textual references, especially for interactions between (ancient) non-literate Bedouin populations and settled literate groups within the Nile Valley. Among these representations we find boxes surrounding textual graffiti. The significance of such boxes has not been studied in depth, but their presence may prove useful for dating and placement purposes and may also provide a means of connecting textual graffiti with figural forms. We also find numerous signs of religious significance, such as pilgrims’ feet in and around pilgrimage destination sites (mainly tombs and temples), and religious images on the exterior walls of temples (such as the Khonsu Temple at Karnak), where the general populace honored the local temple gods.

graffiti drawings made on rocks

“The range of figures bearing figural graffiti is immense and often exhibits some connection to the location in which the figures were found. Thus sites that had religious significance, such as temples and shrines, may feature a large number of representations of deities—either anthropo- morphic images or examples of animals sacred to the local deity (rams, vultures, falcons, bulls, and the like are all seen in various contexts). One complicating aspect of the role of figural graffiti in temple areas is the question of whether the exterior walls, where most of these graffiti are found, bore official decoration (scenes and/or hieroglyphic inscriptions), for we find examples where people emulated already existing decorations by replicating, for example—and usually on a smaller scale—a deity (standing or seated on a throne), an offering table, a sacred bark, or a flower bouquet. In many cases the quantity and size of the graffiti were contingent on the amount of relatively flat space available. In quarries and in way-stops on caravan routes, figural graffiti depicting the “composer” are common, as are depictions of desert animals, cattle, donkeys, and camels.

Over time some sites became contested areas, competed over by several parties. A classic example of this is the Temple of Isis on the island of Philae where Egyptians, Nubians, Greeks, Romans, and later Coptic Christians, each claimed access and rights to all or part of the island. Each group had its own priority and wrote its own culturally designated graffiti there (mostly textual, although some figural examples are present). A similar situation can be found in the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings: on the tomb walls we frequently find examples of textual graffiti left by Greek, and Greek-speaking Egyptian, visitors, as well as some figural graffiti. Later the Coptic Christians usurped these spaces, converting the tombs into sites dedicated to local martyrs (for example, the martyr Appa Ammonias in the tomb of Ramses IV) by drawing abundant crosses and figures of the local saint.

“Certain sites may prove over time to have greater significance as we learn more of the nature of figural graffiti in their original context. What may have motivated the composers of these graffiti is often not known. One site that may prove instructional with further study is the quarry of Abdel Qurna just north of Asyut on the Nile’s east bank. The site contains a large number of both figural and textual graffiti. On the face of the cliff is a “wall” of boat graffiti, where over the centuries visitors continually expanded the number of examples of boats portrayed. Preliminary dating suggests that the boat graffiti include a range of examples dating from late Predynastic times through the Late Period (712–332 B.C.). It is possible that later visitors to the site found the earlier boat graffiti and emulated them with contemporary examples. We do not yet know why boat graffiti are displayed at this particular site. What we can say is that in the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.) and Late Period the site was principally a limestone quarry, similar to a number of adjacent sites. Over time numerous groups came to quarry stone for official uses and left remains of their visits, as evidenced by the graffiti.

“In Egypt it appears that, over time, the number of figural graffiti decreased. One could argue that this indicates that earlier communication methods (including figural graffiti) were being replaced by textual graffiti and subsequently hypothesize that, as the culture became more literate, figural graffiti were abandoned in favor of textual forms. However, the Egyptian evidence shows that this cannot be the case. Since the hieroglyphic writing system remained figural in essence until the Coptic stage of the language, the appearance of “textual” graffiti in Egypt was simply an extension and continuation of the figural graffiti forms within the Egyptian context. Thus at the quarry of Abdel Qurna we have the 19th-Dynasty stela of the scribe Mehy and a cartouche of 26th-Dynasty pharaoh Apries. Each is in essence a figural graffito, as the images represent an aspect of the individual (or agents of the individual) visiting the site. That both contain “texts” simply indicates that they can be considered a different variety of figural graffiti. Hieroglyphs—in which text and picture are one—are thus, in a sense, an advanced form of figural graffiti.

“When we analyze most sites where graffiti are found (in the present context, “graffiti” refers to unofficial inscriptions), we can see that Egyptian culture was unique in its ability to pass seemlessly from rock art to text over time in a way that only cultures utilizing figural writing systems could. That Coptic graffiti are also found at the site of Abdel Qurna may indicate that even after the figural system had passed away, the alphabetic system utilized earlier scriptural techniques and locational criteria.”

Libyan Cave Art

People Who Made the Saharan Rock Art

Little is known about the artists that created the Saharan art work. They may be ancestors of people that still roam the desert or they may be ancestors of people that live today in the Sahel or areas further south in Africa. The long hairdos of some rock art figures found in Libya are similar to those of the modern Wodaadbe people of Niger. Body decorations found on rock art images in Chad resemble body art that found in the Surma of southern Ethiopia today.

When the Sahara dried out the people that lived there migrated southward. Rock art found in southern Africa that is similar to that found in the Sahara is thought to have been introduced there by herdsman originally from North Africa who migrated southward over the generations until they reached southern Africa.

Bushmen paintings in southern Africa and the Bushmen themselves have been studied for insight into the art and artists.

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024