Home | Category: Education, Transportation and Health

FIRST WHEELS AND WHEELED VEHICLES

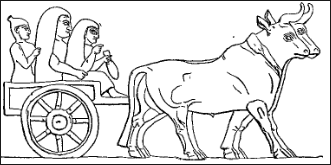

Assyrian cart The wheel, some scholars have theorized, was first used to make pottery and then was adapted for wagons and chariots. The potter’s wheel was invented in Mesopotamia in 4000 B.C. Some scholars have speculated that the wheel on carts were developed by placing a potters wheel on its side. Other say: first there were sleds, then rollers and finally wheels. Logs and other rollers were widely used in the ancient world to move heavy objects. It is believed that 6000-year-old megaliths that weighed many tons were moved by placing them on smooth logs and pulling them by teams of laborers.

Early wheeled vehicles were wagons and sleds with a wheel attached to each side. The wheel was most likely invented before around 3000 B.C. — the approximate age of the oldest wheel specimens — as most early wheels were probably shaped from wood, which rots, and there isn't any evidence of them today. The evidence we do have consists of impressions left behind in ancient tombs, images on pottery and ancient models of wheeled carts fashioned from pottery.◂

Evidence of wheeled vehicles appears from the mid 4th millennium B.C., near-simultaneously in Mesopotamia, the Northern Caucasus and Central Europe. The question of who invented the first wheeled vehicles is far from resolved. The earliest well-dated depiction of a wheeled vehicle — a wagon with four wheels and two axles — is on the Bronocice pot, clay pot dated to between 3500 and 3350 B.C. excavated in a Funnelbeaker culture settlement in southern Poland. Some sources say the oldest images of the wheel originate from the Mesopotamian city of Ur A bas-relief from the Sumerian city of Ur — dated to 2500 B.C. — shows four onagers (donkeylike animals) pulling a cart for a king. and were supposed to date sometime from 4000 BC. [Partly from Wikipedia]

In 2003 — at a site in the Ljubljana marshes, Slovenia, 20 kilometers southeast of Ljubljana — Slovenian scientists claimed they found the world’s oldest wheel and axle. Dated with radiocarbon method by experts in Vienna to be between 5,100 and 5,350 years old the found in the remains of a pile-dwelling settlement, the wheel has a radius of 70 centimeters and is five centimeters thick. It is made of ash and oak. Surprisingly technologically advanced, it was made of two ashen panels of the same tree. The axle, whose age could not be precisely established, is about as old as the wheel. It is 120 centimeters long and made of oak. [Source: Slovenia News]

The invention of the wheel paved the way for more advanced technology such as pulleys, gears, cogs and screws. A flint point or stick spun with a bow was another important advancement. It could be used to make fire and employed as a drill.

See Separate Article ANCIENT HORSEMEN AND THE FIRST WHEELS, CHARIOTS AND MOUNTED RIDERS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World” by David W. Anthony (2010) Amazon.com;

“Babylonia, the Gulf Region, and the Indus: Archaeological and Textual Evidence for Contact in the Third and Early Second Millennia B.C.” by Steffen Laursen and Piotr Steinkeller Amazon.com

“Domestic Animals of Mesopotamia” (2 vols.) -- BSA vols. 7-8

by Nicholas Postgate and Marvin Powell (1993) Amazon.com;

“Domestic Animals of Mesopotamia Part II (Bulletin on Sumerian Agriculture, VIII) by unknown author Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City“ by Gwendolyn Leick (2001) Amazon.com;

“Early Urbanizations in the Levant: A Regional Narrative” by Raphael Greenberg (2002) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Stephen Bertman (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: Life in the Cradle of Civilization” by Amanda H Podany (2018) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat (1998) Amazon.com;

“Society and the Individual in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Laura Culbertson, Gonzalo Rubio (2024) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Babylon and Assyria” by Georges Contenau (1954) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

“Neo-Babylonian Letters and Contracts from the Eanna Archive” (Yale Oriental Series: Cuneiform Texts) by Eckart Frahm and Michael Jursa (2011) Amazon.com;

Donkeys, Onagers and Kunga in Ancient Mesopotamia

The Sumerians had no camels or horses. They did have sheep, goats and oxen which could be used as beasts of burden. Wheeled vehicles were used as carts. Most were pulled by oxen, onagers (donkeylike animals) or donkeys. A bas-relief from the Sumerian city of Ur (2500 B.C.) shows four onagers pulling a cart for a king.

writing cuneiform

Donkeys and onagers were the main beasts of burden. Goods were moved overland by donkey caravans. Donkeys and onagers later were replaced by horses who are less stubborn, faster, and have a lower threshold of pain (donkey's often do not move even when furiously whipped). The Assyrians and Egyptians used horses and chariots. The Hittites and the Hykos were the first people in the Middle East to use chariots. Chariots came before mounted riders.

Marley Brown wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Sumerian scribes wrote of another type of equid, the family that includes horses, donkeys, and zebras. These animals were used to pull war wagons in battle and were given as royal dowries. The precise zoological classification of these animals, called kungas — a transliteration of the ancient Akkadian symbol meaning hybrid equid — had never been determined. Recently, a team of researchers analyzed the remains of equids that were discovered in a cemetery dating to between 2600 and 2200 B.C. at the site of Umm el-Marra in what is now Syria. They concluded that the characteristics of the animals’ skeletons do not fit with those of donkeys, which arrived in Mesopotamia from Egypt, where they were first domesticated around 3800 B.C. They also do not fit with those of a type of local wild ass called a hemippe that went extinct in the 1920s. [Source: Marley Brown, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2022

The team sequenced the genomes of the Umm el-Marra equids and two hemippes that survived into the early twentieth century as well as the genome of an 11,000-year-old hemippe discovered at Göbekli Tepe in Turkey. They determined that the animals buried at Umm el-Marra were hybrid offspring of female domesticated donkeys and male hemippes. This, says paleogeneticist Eva-Maria Geigl of the Jacques Monod Institute, is the earliest known evidence of animal hybridization. “Before they acquired horses, ancient Mesopotamians needed fast, strong equids that they could train to carry soldiers into battle,” says Geigl. “Donkeys are cautious, smart animals that will not run, especially not towards a hostile force, while wild asses, who are fast and less fearful, are virtually untamable.” By breeding kungas, Geigl explains, ancient Mesopotamians combined the optimal traits of both animals. However, while the offspring would have been healthy, they would also have been sterile, meaning the hybridization process would have had to be repeated for every generation.

See Separate Article: ONAGERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Horses in Ancient Mesopotamia

Domesticated horses are thought to have arrived in Mesopotamia around 2000 B.C. Assyria was famous for horses. A good deal of the correspondence from the Assyrian period relates to the importation of horses from Eastern Asia Minor for the stables of the Assyrian King. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The following is a specimen of what they are like: “To the king my lord, thy servant Nebo-sum-iddin: Salutation to the king my lord; for ever and ever may Nebo and Marduk be gracious to the king my lord. Thirteen horses from the land of Kusa, 3 foals from the land of Kusa — in all 16 draught-horses; 14 stallions; altogether 30 horses and 9 mules — in all 39 from the city of Qornê: 6 horses from the land of Kusa; 3 foals from Kusa — in all 9 draught-horses; 14 stallions; altogether 23 horses and 9 mules — in all 28 from the city of Dâna (Tyana): 19 horses of Kusa and 39 stallions — altogether 57 from the city of Kullania (Calneh); 25 stallions and 6 mules — in all 31 from the city of Arpad. All are gelded. Thirteen stallions and 10 mules — altogether 23 from the city of Isana. In all 54 horses from Kusa and 104 stallions, making 148 horses and 30 mules — altogether 177 have been imported. (Dated) the second day of Sivan.”

The land of Kusa is elsewhere associated with the land of Mesa, which must also have lain to the north-west of Syria among the valleys of the Taurus. Kullania, which is mentioned as a city of Kusa, is the Calneh of the Old Testament, which Isaiah couples with Carchemish, and of which Amos says that it lay on the road to Hamath. The whole of this country, including the plains of Cilicia, has always been famous for horsebreeding, and one of the letters to the Assyrian King specially mentions Melid, the modern Malatiyeh, as exporting them to Nineveh. Here the writer, after stating that he had “inscribed in a register the number of horses” that had just arrived from Arrapakhitis, goes on to say: “What are the orders of the king about the horses which have arrived this very day before the king? Shall they be stabled in the garden-palace, or shall they be put out to grass? Let the king my lord send word whether they shall be put out to grass or whether they are to be stabled?”

Roads in Mesopotamia

Satellite imagery had been used to map ancient roads throughout Mesopotamia, including a network or roads between Nineveh and Tell Brak, an ancient site near Aleppo, Syria. Some of the roads were more than 400 feet wide. The images show where the road were. Shallow depressions were left by heavy animal traffic when they were used. This harden the surface and caused the roadway to sink, leaving behind troughs that retained moisture and helped plants grow. The satellite images picked up the subtle changes in growth.

Mesopotamia was where some of the first great trade routes were established. "Control of the Euphrates," an Italian archaeologist Paolo Matthiae told National Geographic, "meant control over the strategic traffic in metals from Anatolia and in wood from the Syrian forests near the Mediterranean, both natural resources essential to Mesopotamian economic life." The only goods available in abundance in Mesopotamia were mud, clay, reeds, palm, fish, and grain. To obtain other goods Mesopotamians needed to trade. Mesopotamians developed large scale trade. Ships brought in goods from distant lands. Labor and grain were exported. Metals were brought in overland routes and paid for with wool and grains. Goods were moved in jars and clay pots. Seals identified who they belonged to.

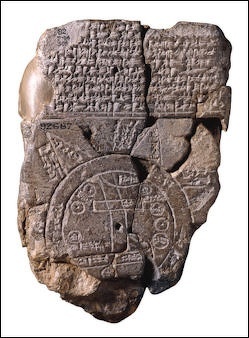

Babylonian map

The Sumerians established trade links with cultures in Anatolia, Syria, Persia and the Indus Valley. Similarities between pottery in Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley indicate that trade probably occurred between the two regions. During the reign of the pharaoh Pepi I (2332 to 2283 B.C.) Egypt traded with Mesopotamian cities as far north as Ebla in Syria near the border of present-day Turkey.

The Sumerians traded for gold and silver from Indus Valley, Egypt, Nubia and Turkey; ivory from Africa and the Indus Valley; agate, carnelian, wood from Iran; obsidian and copper from Turkey; diorite, silver and copper from Oman and coast of Arabian Sea; carved beads from the Indus valley; translucent stone from Oran and Turkmenistan; seashell from the Gulf of Oman. Raw blocks of lapis lazuli are thought to have been brought from Afghanistan by donkey and on foot. Tin may have come from as far away as Malaysia but most likely came from Turkey or Europe.

Many goods that traveled through the Persian Gulf went through the island of Bahrain. There was an early Bronze Age trade network between Mesopotamia, Dilmun (Bahrain), Elam (southwestern Iran), Bactria (Afghanistan) and the Indus Valley. Ivory combs, carnelian belts and beads were carried by ship to Dilmun in Bahrain where buyers from Ur snapped them up the Euphrates and carried them to Mesopotamia.

Bridges and Tolls in Ancient Mesopotamia

Sippara lay on both sides of the Euphrates, like Babylon, and its two halves were probably connected by a pontoon-bridge, as we know was the case at Babylon. Tolls were levied for passing over the latter, and probably also for passing under it in boats. At all events a document translated by Mr. Pinches shows that the quay-duties were paid into the same department of the government as the tolls derived from the bridge.[Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The document, which is dated in the twenty-sixth year of Darius, is so interesting that it may be quoted in full: “The revenue derived from the bridge and the quays, and the guard-house, which is under the control of Guzanu, the captain of Babylon, of which Sirku, the son of Iddinâ, has charge, besides the amount derived from the tolls levied at the bridge of Guzanu, the captain of Babylon, of which Muranu, the son of Nebo-kin-abli, and Nebo-bullidhsu, the son of Guzanu, have charge: Kharitsanu and Iqubu (Jacob) and Nergal-ibni are the watchmen of the bridge. Sirku, the son of Iddinâ, the son of Egibi, and Muranu, the son of Nebo-kin-abli, the son of the watchman of the pontoon, have paid to Bel-asûa, the son of Nergal-yubal-lidh, the son of Mudammiq-Rimmon, and Ubaru, the son of Bel-akhi-erba, the son of the watchman of the pontoon, as dues for a month, 15 shekels of white silver, in one-shekel pieces and coined. Bel-asûa and Ubaru shall guard the ships which are moored under the bridge. Muranu and his trustees, Bel-asûa and Ubaru, shall not pay the money derived from the tolls levied at the bridge, which is due each month from Sirku in the absence of the latter. All the traffic over the bridge shall be reported by Bel-asûa and Ubaru to Sirku and the watchmen of the bridge.”

Three Ox-Drivers from Adab

“Three Ox-Drivers from Adab” goes: “There were three friends, citizens of Adab, who fell into a dispute with each other, and sought justice. They deliberated the matter with many words, and went before the king. "Our king! We are ox-drivers. The ox belongs to one man, the cow belongs to one man, and the waggon belongs to one man. We became thirsty and had no water. [Source: J.A. Black, G. Cunningham, E. Robson, and G. Zlyomi 1998, 1999, 2000, Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford University, piney.com]

Babylonian model of chariot

“We said to the owner of the ox, "If you were to fetch some water, then we could drink!". And he said, "What if my ox is devoured by a lion? I will not leave my ox!". We said to the owner of the cow, "If you were to fetch some water, then we could drink!". And he said, "What if my cow went off into the desert? I will not leave my cow!". We said to the owner of the waggon, "If you were to fetch some water, then we could drink!". And he said, "What if the load were removed from my waggon? I will not leave my waggon!". "Come on, let's all go! Come on, and let's return together!" " "First the ox, although tied with a leash , mounted the cow, and then she dropped her young, and the calf started to chew up the waggon's load. Who does this calf belong to? Who can take the calf?"

” The king did not give them an answer, but went to visit a cloistered lady. The king sought advice from the cloistered lady: "Three young men came before me and said: 'Our king, we are ox-drivers. The ox belongs to one man, the cow belongs to one man, and the waggon belongs to one man. We became thirsty and had no water. We said to the owner of the ox, "If you were to draw some water, then we could drink!". And he said, "What if my ox is devoured by a lion? I will not leave my ox!". We said to the owner of the cow, "If you were to draw some water, then we could drink!". And he said, "What if my cow went off into the desert? I will not leave my cow!". We said to the owner of the waggon, "If you were to draw some water, then we could drink!". And he said, "What if the load were removed from my waggon? I will not leave my waggon!" he said. "Come on, let's all go! Come on, and let's return together!" ' "

" 'First the ox, although tied with a leash , mounted the cow, and then she dropped her young, and the calf started to chew up the waggon's load. Who does this calf belong to? Who can take the calf?" ' [35 lines missing, The cloistered lady continues her reply to the king:) "Well now, the owner of the ox, ...... his field ....... After his ox has been eaten by a lion ......, his field ......." "The hero....... Like a mountaineer ....... A dog ...... the ox ....... A strong man ...... in his field......."

"Well now, the owner of the cow ...... his wife. After his cow has gone off into the desert ......, his wife will walk the streets ....... After the cow has dropped its young ......, the hero, walking in the rain ....... His wife ...... herself. The ox's food ration which he has turned to his ......, ...... hunger. His wife dwells with him in his house, his desired one ...... "

"Well now, the owner of the waggon, after he has abandoned his ......, and the load has been removed from his waggon, and ...... from his waggon, and after he has brought his ...... into his house, ...... will be made to leave his house. His calf that began to chew up the waggon's load will be ...... in his house. When he has approached ...... the open-armed hero, the king, having learnt about his case, will make his ...... leave his dwelling. ...... the ox, ...... has partaken of my wisdom, shall not oppose it. His load, ......, will not return ."

“When the king came out from the cloistered lady's presence, each man's heart was dissatisfied. The man who hated his wife left his wife. The man ...... his ...... abandoned his ....... With elaborate words, with elaborate words, the case of the citizens of Adab was settled. Pa-nijin-jara, their sage, the scholar, the god of Adab, was the scribe.”

See Abraham and the Ox Cart travel to Canaan

Assyrian Chariots

The Assyrians employed sophisticated siege tactics, and formed corps ancillary to the army's main fighting force but they were primarily a chariot-based force. Fighting chariots often accommodated two people — one rider and one archer. Early charioteers often swept down out of the mountains, encircled their flat-footed and unarmored foes, and picked them off from 100 or 200 yards away with arrows fired from sophisticated bows.

The ruthless, formidable and well organized Assyrians were perhaps the greatest charioteers of the ancient world. They dominated the ancient world from the 9th century to 7th century B.C. , when they were replaced by the Persians, a people that used chariots to create a huge empire that stretched from Greece to India.

Most of what is known about Assyrian chariots has been gleaned from alabaster reliefs now in the British Museum. Their chariots come in a lightweight two-horse model and a heavier four-horse version. They appear to have been made from wood and rawhide.Chariots ruled the world until foot soldiers in Alexander the Great's army learned to withstand chariot advances by aiming their weapons at the horses first: wearing arrow-proof armor and shields; and organizing themselves into tight chariot-proof ranks.

See Separate Article: ASSYRIAN MILITARY: CAMPAIGNS, WEAPONS, PERSONNEL africame.factsanddetails.com

Boats in Ancient Mesopotamia

The first Mesopotamian boats were used to travel on rivers. Later most sophisticated vessels with sails were developed. The Mesopotamians invented the sail. Seafaring voyages may have taken place as early as 3500 B.C. Mesopotamians traveled across the Persian Gulf and Arabian Sea between Persia and India.

“The cry of the Chaldeans,” according to the Old Testament, was “in their ships,” and in the earliest age of Babylonian history, Eridu, which then stood on the sea-coast, was already a seaport. But Assyria was too far distant from the sea for its inhabitants to become sailors, and the rapid current of the Tigris made even river navigation difficult. In fact, the rafts on which the heavy monuments were transported, and which could float only down stream, or the small, round boats, resembling the kufas that are still in use, were almost the only means employed for crossing the water. When the Assyrian army had to pass a river, either pontoons were thrown across it, or the soldiers swam across the streams with the help of inflated skins. The kufa was made of rushes daubed with bitumen, and sometimes covered with a skin. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

So little accustomed were the Assyrians to navigation that, when Sennacherib determined to pursue the followers of Marduk-baladan across the Persian Gulf to the coast of Elam, he was obliged to have recourse to the Phoenician boat-builders and sailors. Two fleets were built for him by Phoenician and Syrian workmen, one at Tel-Barsip, near Carchemish, on the Euphrates, the other at Nineveh on the Tigris; these he manned with Syrian, Sidonian, and Ionian sailors, and after pouring out a libation to Ea, the god of the sea, set sail from the mouth of the Euphrates. It was probably for the support of this fleet that the 20 talents (£10,800) annually levied on the district of Assur were intended. The Phoenician ships employed by the Assyrians were biremes, with two tiers of oars. Of the Babylonian fleet we know but little. It does not seem to have taken part in the defence of the country at the time of the invasion of Cyrus.

Some documents translated by Mr. Pinches throw light on the building and cost of the ships. One of them is as follows: “A ship of six by the cubit beam, twenty by the cubit the seat of its waters, which Nebobaladan, the son of Labasi, the son of Nur-Papsukal, has sold to Sirikki, the son of Iddinâ, the son of Egibi, for four manehs, ten shekels of silver, in one-shekel pieces, which are not standard, and are in the shape of a bird's tail (?). Nebo-baladan takes the responsibility for the management (?) of the ship. Nebo-baladan has received the money, four manehs ten shekels of white (silver), the price of his ship, from the hands of Sirikki.” The contract, which was signed by six witnesses, one of whom was “the King's captain,” was dated at Babylon in the twenty-sixth year of Darius.

Ferries and Cargo Boats in Ancient Mesopotamia

Transport of cedar Cargo and ferry-boats are frequently mentioned in letters and contracts. Reference has already been made to the shekel and a quarter paid by the agent of Belshazzar for the hire of a boat which conveyed three oxen and twenty-four sheep to the temple of the Sun-god at Sippara, in order that they might be sacrificed at the festival of the new year. Sixty qas of dates were at the same time given to the boatmen. In the reign of Nebuchadnezzar, 3 shekels were paid for the hire of a grain-boat, and in the thirty-sixth year of the same King 4½ shekels were given for the hire of another boat for the transport of wool. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

One letter describes the writer's journey to Elam and Arrapakhitis, while another relates to a ferry-boat and the boat-house in which it was kept. The boat-house, we are told, had fallen into decay in the reign of Hammurabi, and was sadly in want of repair, while the chief duty of the writer, who seems to have been the captain of the boat, was to convey the merchants who brought various commodities to Babylon. If the merchant, the letter states, was furnished with a royal passport, “we carried him across” the river; if he had no passport, he was not allowed to go to Babylon. Among other purposes for which the vessel had been used was the conveyance of lead, and it was capable of taking as much as 10 talents of the metal. We further gather from the letter that it was the custom to employ Bedouin as messengers.

There is no hire paid for the slaves or interest on the money. Another possessor shall not have power over them until Musezib receives the money, two manehs ten shekels of white silver, in one-shekel pieces. Sisku, the son of Iddinâ, takes the responsibility for the non-escape of Musezibtum and Narum. The day when Musezibtum and Narum go elsewhere Sisku shall pay Musezib half a measure of grain a day by way of hire. The money, which is for a ship for the bridge, has been given to Sisku.” This contract is also dated in the twenty-sixth year of Darius.

A letter written in the time of Hammurabi, or Amraphel, throws some light on the profits that were made by conveying passengers. There were ships which conveyed foreign merchants to Babylon if they were furnished with passports allowing them to travel and trade in the dominions of the Babylonian King. They took their goods and commodities along with them; on one occasion, we are told, the boat in which some of them travelled had been used for the conveyance of 10 talents of lead. It must, therefore, have been of considerable size and draught. That the army and navy should have been recruited from abroad was in accordance with that spirit of liberality toward the foreigner which had distinguished the Babylonians from an early period. It was partly due to the mixed character of the race, partly to the early foundation of an empire which embraced the greater portion of Western Asia, partly, and more especially, to the commercial instincts of the people. We find among them none of that jealous exclusiveness which characterized most of the nations of antiquity. They were ready to receive into their midst both the foreigner and his gods.

Another contract relates a boat and a pontoon-bridge which ran across the Euphrates and connected the two parts of Babylon together: “[Two] manehs ten shekels of white (silver), coined in oneshekel pieces, not standard, from Musezib, the son of Pisaram, to Sisku, the son of Iddinâ, the son of Egibi. Musezibtum and Narum, his female slaves — the wrist of Musezibtum is tattooed with the name of Iddinâ, the father of Sisku, and the wrist of Narum is tattooed with the name of Sisku — are the security of Musezib.

Hammurabi's Code of Laws on Shipbuilders and Sailors

234) If a shipbuilder build a boat of sixty gur for a man, he shall pay him a fee of two shekels in money.

235) If a shipbuilder build a boat for some one, and do not make it tight, if during that same year that boat is sent away and suffers injury, the shipbuilder shall take the boat apart and put it together tight at his own expense. The tight boat he shall give to the boat owner.

236) If a man rent his boat to a sailor, and the sailor is careless, and the boat is wrecked or goes aground, the sailor shall give the owner of the boat another boat as compensation.

237) If a man hire a sailor and his boat, and provide it with corn, clothing, oil and dates, and other things of the kind needed for fitting it: if the sailor is careless, the boat is wrecked, and its contents ruined, then the sailor shall compensate for the boat which was wrecked and all in it that he ruined.

238) If a sailor wreck any one's ship, but saves it, he shall pay the half of its value in money.

239) If a man hire a sailor, he shall pay him six gur of corn per year.

240) If a merchantman run against a ferryboat, and wreck it, the master of the ship that was wrecked shall seek justice before God; the master of the merchantman, which wrecked the ferryboat, must compensate the owner for the boat and all that he ruined.

Journey of Nanna to Nippur

Nanna was the Mesopotamian Moon god and patron of herdsmen. Thorkild Jacobsen wrote in “The Treasures of Darkness”: The “Journey of Nanna to Nippur” “myth is closely connected with the spring rite of the first fruits which were taken from Ur to Nippur, stopping over all sacred cities on the way to the temple of Enlil, the Ekur in Nippur. The meaning of this ritual act was a religious celebration and sanction of the exchange of products between the cities of the Southern marshes and the farmers in the North [Source: Jacobsen, Thorkild, The Treasures of Darkness, 1976, Yale University).

“To go to his city, to stand before his father,

Ashgirbabbar (Nanna) set his mind:

"I, the hero, to my city I would go, before my father I would stand;

I, Sin, to my city I would go, before my father I would stand,

Before my father I would stand."

(then he proceeds to load his boat with a rich assortment of trees, plants and animals. On his journey from Ur to Nippur, Nanna and his boat stop at five cities: Im, Larsa, Uruk and two cities whose names are illegible; in each of these, Nanna is met and greeted by the representative tutelary deity. Then he arrives at Nippur:)

[Source: Kramer, Samuel Noah (1988) “Sumerian Mythology,” University of Pennsylvania Press, West Port, Connecticut].

At the lapis lazuli quay, the quay of Enlil,

Nanna-Sin drew up his boat,

At the white quay, the quay of Enlil,

Ashbirbabbar drew up his boat,

On the ....... of the father, his begetter, he stationed himself,

To the gatekeeper of Enlil he says:

" Open the house, gatekeeper, open the house

Open the house, O protecting genie, open the house

Open the house, thou who makest the trees come forth, open the house,

O ...... who makest the trees come forth, open the house,

“Gatekeeper, open the house, O protecting genie, open the house",

Joyfully, the gatekeeper joyfully opened the door,

The protecting genie who makes the trees come forth, joyfully

The gatekeeper joyfully opened the door

He who makes the trees come forth, joyfully

The gatekeeper joyfully opened the door,

With Sin, Enlil rejoiced.

Then Nanna feasts with Enlil and afterwards addresses his father Enlil as follows:

" In the river give me overflow,

In the field give me much grain,

In the swampland give me grass and reeds,

In the forests give me...

In the plains give me...

In the palm-grove and vineyard give me honey and wine,

In the palace give me long life,

To Ur I shall go".

Enlil accedes to Nanna’s request:

He gave him, Enlil gave him,

To Ur he went,

In the river he gave him overflow,

In the field he gave him much grain,

In the swampland he gave him grass and reeds,

In the forests he gave him...

In the plain he gave him...

In the palm-grove and vineyard he gave him honey and wine,

In the palace he gave him long life.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024