Home | Category: Assyrians / Government and Legal System

ASSYRIAN WARFARE

For the Assyrians war was almost a business and they profited mightily from the rewards of conquest. The Assyrians began using iron weapons and armor in Mesopotamia around 1200 B.C. (After the Hittites but before the Egyptians) with deadly results. The also effectively employed war chariots. They were not the first to do this but they were the first to organize them into a cavalry.

The Assyrians according to some scholars possessed the first long-range armies. They utilized supply depots, a sophisticated road network, transport columns, and bridging trains to campaigns as far away as 300 miles from their home base and moved as rapidly as armies during World War I (30 miles a day). To get across rivers they used boats made from inflated animals skins, and, while campaigning, they carried few supplies, living instead off of food captured in enemy territory. Artwork depicts Assyrian soldiers destroying buildings with pickaxes and crowbars and then, carrying off booty. [Source: “History of Warfare” by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Towns that refused to pay tribute were sacked. According to one tablet one town was “crushed like a clay pot” and the population and leaders were made prisoners “like a herd of sheep” as the Assyrian army carried away booty.

One image of an Assyrian army attacking a city shows some of the techniques the Assyrians used to capture a city. On the left side of the image some men scale the wall with a ladder. On the right side a wheeled battering ram is used to destroy the city walls. Three figures at the top next to the city have been impaled on spikes. The tall figure on the far right with the long clothes is Tiglath Pileser III, who is refered to in the Bible by his Babylonian name, Pul.

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Ancient Assyrians: Empire and Army, 883–612 BC” by Mark Healy (2000) Amazon.com;

“Landscapes of Warfare: Urartu and Assyria in the Ancient Middle East” by Tiffany Earley-Spadoni (2025) Amazon.com;

“On Ancient Warfare: Perspectives on Aspects of War in Antiquity 4000 BC to AD 637"

by Richard A Gabriel (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Assyrian Army I.: The Structure of the Neo-Assyrian Army as Reconstructed from the Assyrian Palace Reliefs and Cuneiform Sources / 2, Cavalry and Chariotry” by Tamás Dezső (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Assyrian Army II / II. Recruitment and Logistics

by Dezső Tamás (2016) Amazon.com;

“Sennacherib at the Gates of Jerusalem: Story, History and Historiography” by Isaac Kalimi and Seth Richardson (2014) Amazon.com;

“Siege: The Story of Hezekiah and Sennacherib” by Thurman C Petty (1980) Amazon.com;

“Relations of Power in Early Neo-Assyrian State Ideology” by Mattias Karlsson (2016) Amazon.com;

“Assyria: The Rise and Fall of the World's First Empire” by Eckart Frahm (2023) Amazon.com;

“Assyrian Empire: A History from Beginning to End” by History Hourly (2019) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Assyria” by Eckart Frahm (2017) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction” by Karen Radner (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Might That Was Assyria” by H. W. F. Saggs (1984) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Assyria” by James Baikie (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: an Enthralling Overview of Mesopotamian History (2022) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: a Captivating Guide (2019) Amazon.com;

“A History of the Ancient Near East” by Marc Van De Mieroop (2003) Amazon.com;

Assyrian Army

The Assyrians established the largest army up to that time in the Mediterranean. Their armies had professional soldiers, infantry, charioteers, mounted archers, fast horses, engineers and wagoners. The most important unit was the royal bodyguard, perhaps the first regular army. The other units were amassed as need arose. In battles the Assyrians used bows, slings, iron swords and lances, battering rams, oil firebombs, but relied on iron javelins.

The Assyrian Army was the most effective force of its time. It was divided mostly into three different categories: 1) Infantry, which included both close-combat troops using spears, and archers, and hired mercenary slingers (stone throwers); 2) cavalry among the finest in the ancient Middle East and included both close-combat cavalry units with spears and mounted archers; and chariots, primarily used in regular land engagements not in sieges. The infantry was highly trained and worked alongside military engineers in order to breach sieges. Mounted archers could be utilized for their agility of the horses alongside long-range attacks. [Source: Wikipedia]

The army was under the command of the Tartannu, or “Commander-in-Chief,” the Biblical Tartan, who, in the absence of the King, led the troops to battle and conducted a campaign. When Shalmaneser II., for example, became too old to take the field himself, his armies were led by the Tartan Daian-Assur, and under the second Assyrian empire the Tartan appears frequently, sometimes in command of a portion of the forces, while the King is employing the rest elsewhere, sometimes in place of the King, who prefers to remain at home. In earlier days there had been two Tartans, one of whom stood on the right hand side of the King and the other on his left. In order of precedence both of them were regarded as of higher rank than the Rab-shakeh. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The army was divided into companies of a thousand, a hundred, fifty, and ten, and we hear of captains of fifty and captains of ten. Under Tiglath- pileser III. and his successors it became an irresistible engine of attack.

The infantry outnumbered the cavalry by about ten to one, and were divided into heavy-armed and light-armed. Their usual dress, at all events, up to the foundation of the second Assyrian empire, consisted of a peaked helmet and a tunic which descended half-way down the thighs, and was fastened round the waist by a girdle. From the reign of Sargon onward they were divided into two bodies, one of archers, the other of spearmen, the archers being partly light-armed and partly heavy-armed.

Assyrian Soldiers

The Assyrian army was originally recruited from the native peasantry, who returned to their fields at the end of a campaign with the spoil that had been taken from the enemy. Under the second Assyrian empire, however, it became a standing army, a part of which was composed of mercenaries, while another part consisted of troops drafted from the conquered populations. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Certain of the soldiers were selected to serve as the body-guard of the King; they had a commander of their own and doubtless possessed special privileges. The army was recruited by conscription, the obligation to serve in it being part of the burdens which had to be borne by the peasantry. They could be relieved of it by the special favor of the government just as they could be relieved of the necessity of paying taxes.

No pains were spared to make it as effective as possible; its discipline was raised to the highest pitch of perfection, and its arms and accoutrements constantly underwent improvements. As long as a supply of men lasted, no enemy could stand against it, and the great military empire of Nineveh was safe.

Weapons, Armor and Clothes of Assyrian Soldiers

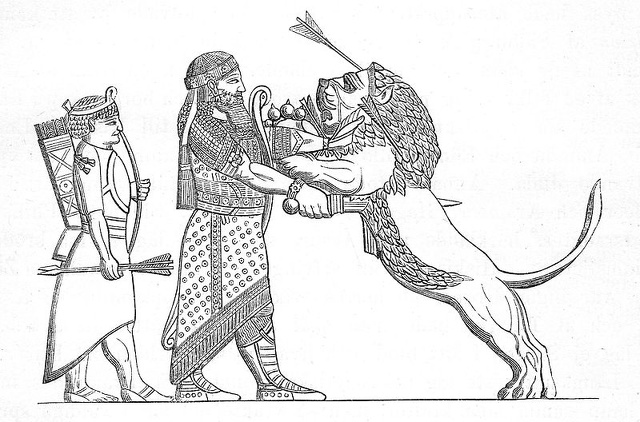

The heavy-armed were again divided into two classes, one of them wearing sandals and a coat-of-mail over the tunic, while the other was dressed in a long, fringed robe reaching to the feet, over which a cuirass was worn. They also carried a short sword, and had sandals of the same shape as those used by the other class. Each had an attendant waiting upon him with a long, rectangular shield of wicker-work, covered with leather. The light-armed archers were encumbered with but little clothing, consisting only of a kilt and a fillet round the head. The spearmen, on the contrary, were protected by a crested helmet and circular shield, though their legs and face were usually bare. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Changes were introduced by Sennacherib, who abolished the inconveniently long robe of the second class of heavy-armed archers, and gave them leather greaves and boots. The first class, on the other hand, are now generally represented without sandals, and with an embroidered turban with lappets on the head. Sennacherib also established a corps of slingers, who were clad in helmet and breastplate, leather drawers, and short boots, as well as a company of pioneers, armed with double-headed axes, and clothed with conical helmets, greaves, and boots.

The heads of the spears and arrows were of metal, usually of bronze, more rarely of iron. The helmets also were of bronze or iron, a leather cap being worn underneath them, and the coats-of-mail were formed of bronze scales sewn to a leather shirt. Many of the shields, moreover, were of metal, though wicker-work covered with leather seems to have been preferred. Battering-rams and other engines for attacking a city were carried on the march.

Assyrian Cavalry

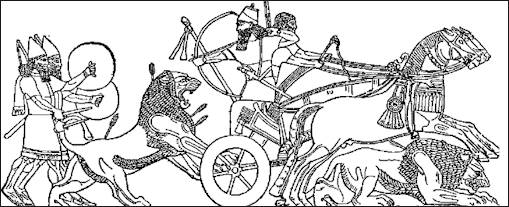

The Assyrians army contained cavalry as well as foot-soldiers. The cavalry had grown out of a corps of chariot-drivers, which was retained, though shrunken in size and importance, long after the more serviceable horsemen had taken its place. The chariot held a driver and a warrior. When the latter was the King he was accompanied by one or two armed attendants. They all rode standing and carried bows and spears. The chariot itself ran upon two wheels, a pair of horses being harnessed to its pole. Another horse was often attached to it in case of accidents. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

At first the cavalry were little more than mounted horsemen. Their only weapons were the bow and arrow, and they rode without saddles and with bare legs. At a later period part of the cavalry was armed with spears, saddles were introduced, and the groom who had run by the side of the horse disappeared. At the same time, under Tiglath-pileser III., the rider's legs were protected by leathern drawers over which high boots were drawn, laced in front. This was an importation from the north, and it is possible that many of the horsemen were brought from the same quarter. Sennacherib still further improved the dress by adding to it a closely fitting coat of mail.

The chariots were of little good when the fighting had to be done in a mountainous country. In the level parts of Western Asia, where good roads had existed for untold centuries, they were a powerful arm of offence, but the Assyrians were constantly called upon to attack the tribes of the Kurdish and Armenian mountains who harassed their positions, and in such trackless districts the chariots were an incumbrance and not a help. Trees had to be cut down and rocks removed in order to make roads along which they might pass.

Assyrian Chariots

The Assyrians employed sophisticated siege tactics, and formed corps ancillary to the army's main fighting force but they were primarily a chariot-based force. Fighting chariots often accommodated two people — one rider and one archer. Early charioteers often swept down out of the mountains, encircled their flat-footed and unarmored foes, and picked them off from 100 or 200 yards away with arrows fired from sophisticated bows.

The ruthless, formidable and well organized Assyrians were perhaps the greatest charioteers of the ancient world. They dominated the ancient world from the 9th century to 7th century B.C. , when they were replaced by the Persians, a people that used chariots to create a huge empire that stretched from Greece to India.

Most of what is known about Assyrian chariots has been gleaned from alabaster reliefs now in the British Museum. Their chariots come in a lightweight two-horse model and a heavier four-horse version. They appear to have been made from wood and rawhide.Chariots ruled the world until foot soldiers in Alexander the Great's army learned to withstand chariot advances by aiming their weapons at the horses first: wearing arrow-proof armor and shields; and organizing themselves into tight chariot-proof ranks.

Assyrians Military Engineers and Supply Trains

The Assyrian engineers indeed were skilled in the construction of roads of the kind, and the inscriptions not infrequently boast of their success in carrying them through the most inaccessible regions, but the necessity for making them suitable for the passage of chariots was a serious drawback, and we hear at times how the wheels of the cars had to be taken off and the chariots conveyed on the backs of mules or horses. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

It was not wonderful, therefore, that the Assyrian kings, who were practical military men, soon saw the advantage of imitating the custom of the northern and eastern mountaineers, who used the horse for riding purposes rather than for drawing a chariot. The chariot continued to be employed in the Assyrian army, but rather as a luxury than as an effective instrument of war. These pioneers were especially needed for engineering the way through the pathless defiles and rugged ground over which the extension of the empire more and more required the Assyrian army to make its way.

Baggage wagons were also carried, as well as standards and tents. The tents of the officers were divided into two partitions, one of which was used as a dining-room, while the royal tent was accompanied by a kitchen. Tables, chairs, couches, and various utensils formed part of its furniture. One of these chairs was a sort of palanquin in the shape of an arm-chair with a footstool, which was borne on the shoulders of attendants.

Assyrian Brutality

Lord Byron wrote that Assyrians went after their neighbors like a “wolf in the fold.” They forced captives to strip naked to show subservience to their captors and slaughtered those who dared to oppose them. Bas-reliefs from the Chaldean campaign (7th century B.C.) show Assyrian victors making piles of heads of their victims, using battering rams and impaling captives.

Stone friezes at Nimrud and Ninevah show war chariots crushing enemy soldiers, women and children and an Assyrian king and queen enjoying drinks in a garden decorated with the head of an enemy leader dangling from a tree. After one of his victories Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal bragged, "I cut off their heads; I burned them with fire; a pile of living men and of heads over against the city gate I set up; men I impaled on stakes; the city I destroyed...I turned it into mounds and ruin heaps; the young men and maidens I burned." Another Assyrian king boasted in 691 BC: "I cut their throats like sheep...My prancing steeds, trained to harness, plunged into their welling blood as into a river; the wheels of battle chariots were bespattered with blood and filth. I filled the plain with corpses of their warriors like herbage.”

The Assyrians reserved their wrath for the people who opposed them. Those that joined their empire were treated well. Among those that resisted the men were killed and the women and children was abducted and resettled in foreign land. The women were encouraged to take new husbands. Cuneiform tables reveal that refugees were given food, shoes, oil and clothes.

The art historian John Russell of the Massachusetts College of Art believes the Assyrian were no more warlike and brutal than other people of their time they were just better at it. He says that the brutal images are found mostly in throne room of Ashurnasirpal’s palace and were intended to intimidate visiting dignitaries. The rooms occupied by kings and queen had no such art. The adornments found there seemed to be there to ward off evil spirits.

Isaiah on Judea and the Assyrians

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “Isaiah's oracles are so intricately related to happenings of his era, that the history of the period must be understood. The following outline is drawn from accounts in II Kings, supplemented by information from Chronicles and Assyrian king records. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org]

“Because there was no outside power strong enough or interested enough to provide any real threat, Israel and Judea prospered in the eighth century. King Adad-nirari III of Assyria in 805 took tribute from Damascus, but Israel, a few miles to the south of the Aramaean capital, was unaffected. A succession of weak rulers reduced the Assyrian threat. Jeroboam II (786-746) expanded his kingdom into the Transjordan area and worked in economic harmony with Phoenician cities. Prosperity and social inequalities graphically pictured by Amos brought hardship and suffering for the underprivileged. Parallel economic growth took place in Judea in Uzziah's time (783-742). Edom was recaptured; trade with Arabia developed through the Red Sea; two cities of Philistia, Gath and Ashdod, became vassals (II Chron. 26:6 f.), and despite the absence of a prophetic record comparable to the book of Amos, conditions condemned by Isaiah when he begins his prophetic work at the King's death suggest that the situation in Judea and Israel was the same.

“746. Jeroboam II died and a period of decline in Israel began. Lack of stability in Israelite leadership, resulting in the assassination of four kings within twenty years, produced a national policy that fluctuated between pro-Egyptian and pro-Assyrian alliances. A sense of aimlessness or lack of direction, clearly reflected in Hosea, made Israel an easy target when Assyrian forces began to move westward and southward.

“745. Tiglath Pileser III (called "Pul" in II Kings 15:19 after "Pulu," the name under which he controlled Babylon) became ruler of Assyria and began an expansionist program. Up to this time, Assyria had periodically raided northern Syria for bounty and to maintain open channels for exploitation of minerals, timber and trade. Assyria's new program included conquest and rule. In addition to subduing Mesopotamian neighbors in the immediate vicinity of Assyria, Tiglath Pileser began subjugation of the west, starting in 743. A coalition of small nations, led by Azriau of Iuda, undoubtedly Uzziah (Azariah) of Judea,, opposed him. The Assyrian account, taken from slabs found at Calah, has many lacunae, but it is clear that Tiglath Pileser subdued his opposition. The records list tribute received from frightened rulers of smaller kingdoms, including Rezin of Damascus and Menahem of Samaria.

“742. Uzziah died and Jotham became king. Because of his father's long illness, Jotham had administrative experience as regent of Judea and was able to give Judea governmental stability that is in complete contrast with the situation in Israel. Uzziah's military program was continued and the Chronicler reports a Judaean victory over Ammonites who paid tribute for three years.

See Separate Article: CONQUEST OF THE JEWISH KINGDOMS BY ASSYRIA africame.factsanddetails.com

Assyrian-Arabian Battle

Sennacherib Military Campaigns

Morris Jastrow said: “Sennacherib (705-681 B.C.) determines upon a more aggressive policy, and at last in 689 B.C., Babylon is taken and mercilessly destroyed. Sennacherib boasts of the thoroughness with which he carried out the work of destruction. He pillaged the city of its treasures. He besieged and captured all the larger cities of the south—Sippar, Uruk, Cuthah, Kish, and Nippur—and when, a few years later, the south organised another revolt, the king, to show his power, put Babylon under water, and thus obliterated almost all vestiges of the past. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: The new Pax Assyriaca was, of course, not unbroken by military campaigns.Sennacherib's unsuccessful siege of Jerusalem in 701 is well known from both the Assyrian and biblical accounts (II Kings 18:13–19:37; Isa. 36–37). His generals campaigned against Cilicia and Anatolia (696–695 B.C.), while his successor Esarhaddon (680–669 B.C.) is perhaps most famous for his conquest of Egypt. Esarhaddon had succeeded to the throne in the troubled times following his father's assassination (cf. II Kings 19:37; Isa. 37:38), and was determined to secure a smoother succession for his own sons. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

See Separate Article: SENNACHERIB MILITARY CAMPAIGNS africame.factsanddetails.com

Assyrians Versus Nubians in Egypt

Taharqa (690–664 B.C.) ruled Egypt-Nubia for 26 years. He needed lots of cedar and juniper from Lebanon to realize his building campaign. When the Assyrian ruler King Esarhaddon tried to shut down the trade, Taharqa sent troops to the southern Levant to support a revolt against the Assyrians. Esarhaddon stopped the effort and launched an attack into Egypt which Taharqa's army pushed back in 674 B.C.

Sennacherib’s son, Esarhaddon, avenged Taharka support for Palestine’s revolt and defeated Taharka’s army. Memphis was captured, along with its royal harem. When Esarhaddon withdrew from Egypt, Taharka returned from his sanctuary in Upper Egypt and massacred all the Assyrians he could get his hands on. He controlled Egypt until he was defeated by Esarhaddon’s son, Ashurbanipal, after which he fled south to Nubia. How Taharqa spent his final years is unknown but he was allowed to remain in power in Nubia. Like his father Piye he was buried in a pyramid. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com]

Robert Draper wrote in National Geographic, The Nubian initial victory against the Babylonians “clearly went to the Nubian's head, Rebel states along the Mediterranean shared his giddiness and entered into an alliance against Esarhaddon. In 671 B.C., the Assyrians marched with their camels into the Sinai desert to quell the rebellion, Success was instant: now it was Esarhaddon who brimmed with bloodlust. He directed his troops towards the Nile Delta."

In 671 B.C. The Assyrians sacked Memphis, “Taharqa and his arm squared off against the Assyrians. For 15 days they fought pitched battles—“very bloody” — by Esarhaddon's own admission. But the Nubians were pushed back all the way to Memphis. Wounded five times Taharqa escaped with his life and abandoned Memphis. In typical Assyrian fashion, Esarhaddon slaughtered the villagers and “erected piles of theirs heads."

The Assyrians later wrote: “His queen, his harem, Ushankhuru his heir, and the rets of his ons and daughters, his property and his goods, his horses, his cattle, his sheep, in countless numbers I carried off to Assyria. The root of Kush I tore up out of Egypt." To commemorate the event a stelae was raised that showed Taharqa's son Ushankhuru, kneeling before the Assyrian king with a rope around his neck.

In 669 B.C. Esarhaddon died on route to Egypt but his successor quickly mounted an assault on Egypt. Taharqa knew he was outnumbered this time and fled to Napata never to return to Egypt again.

Lack of an Assyrian Navy

If Babylonia copied Assyria in military arrangements, the converse was the case as regards a fleet. “The cry of the Chaldeans,” according to the Old Testament, was “in their ships,” and in the earliest age of Babylonian history, Eridu, which then stood on the sea-coast, was already a seaport. But Assyria was too far distant from the sea for its inhabitants to become sailors, and the rapid current of the Tigris made even river navigation difficult. In fact, the rafts on which the heavy monuments were transported, and which could float only down stream, or the small, round boats, resembling the kufas that are still in use, were almost the only means employed for crossing the water. When the Assyrian army had to pass a river, either pontoons were thrown across it, or the soldiers swam across the streams with the help of inflated skins. The kufa was made of rushes daubed with bitumen, and sometimes covered with a skin. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

So little accustomed were the Assyrians to navigation that, when Sennacherib determined to pursue the followers of Marduk-baladan across the Persian Gulf to the coast of Elam, he was obliged to have recourse to the Phœnician boat-builders and sailors. Two fleets were built for him by Phœnician and Syrian workmen, one at Tel-Barsip, near Carchemish, on the Euphrates, the other at Nineveh on the Tigris; these he manned with Syrian, Sidonian, and Ionian sailors, and after pouring out a libation to Ea, the god of the sea, set sail from the mouth of the Euphrates. It was probably for the support of this fleet that the 20 talents (£10,800) annually levied on the district of Assur were intended.

The Phœnician ships employed by the Assyrians were biremes, with two tiers of oars. Of the Babylonian fleet we know but little. It does not seem to have taken part in the defence of the country at the time of the invasion of Cyrus.

But the sailors who manned it were furnished with food, like the soldiers of the army, from the royal storehouse or granary. Thus in the sixteenth year of Nabonidos we have a memorandum to the effect that 210 qas of dates were sent from the storehouse in the month Tammuz “for the maintenance of the sailors.” The King also kept a state-barge on the Euphrates, like the dahabias of Egypt. In the twenty-fourth year of Darius, for instance, a new barge was made for the monarch, two contractors undertaking to work upon it from the beginning of Iyyar, or April, to the end of Tisri, or September, and to use in its construction a particular kind of wood.

Evidence of a Soft Assyrian Touch

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: In the course of establishing the largest empire in the history of the world up to that point, the Assyrians needed to find ways to bring a diverse range of peoples into their orbit. At times, this involved such heavy-handed tactics as forcibly moving large groups to the Assyrian heartland, where they would be indoctrinated into the Assyrian worldview. But the Assyrians also employed more subtle approaches, as illustrated by a recently discovered underground complex in the village of Başbük in southeastern Turkey. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2022]

The site came to the attention of authorities after it was targeted by looters, who had cut into it through the floor of a modern two-story house. “The looters must have hoped to find treasure,” says archaeologist Mehmet Önal of Harran University, who led a rescue excavation of the complex in 2018. “They were caught showing photos of carvings from the complex and looking for customers to buy them.” Önal and his team found that the complex, which was carved out of limestone bedrock, consists of an entrance chamber and an upper and lower gallery. In the upper gallery, they cleared away sediment to reveal a 13-foot-wide relief panel carved into the rock wall that appeared to depict a procession of eight gods and goddesses.

The excavation was cut short due to the site’s instability, but Önal was intrigued by the panel and sent photographs of it to Selim Ferruh Adalı, an ancient historian at the Social Sciences University of Ankara. Adalı was struck by the panel’s unusual blend of Assyrian and local Aramaean features. He was able to identify the first four deities in the procession—three of them based on their attire and accoutrements as well as short inscriptions in Aramaic, the language of the local people in Neo-Assyrian times. First and largest is the storm god Hadad, the dominant deity of northern Syria and southeastern Anatolia in the first millennium B.C., carrying his lightning bundle and wearing a large encircled star on his head. Following Hadad is his consort, Attar’atte, a mother-goddess of fertility and protection, who is depicted wearing a double-horned, cylindrical crown on which a star is set. Next is the moon god Sin, who sports headgear crowned with a crescent and full moon. The fourth deity is recognizable as the sun god Shamash based on the winged sun-disk crown he wears, but the remaining four deities cannot be clearly identified. A longer Aramaic inscription on the panel is largely illegible, but appears to include the name Mukın-abūa of Tušhan, the Assyrian official in charge of the region during the reign of the Neo-Assyrian king Adad-nirari III (r. 810–783 B.C.). While the panel features gods worshipped locally, they are depicted with traits typically found in Assyrian art such as the style of beards and of the muscles in Hadad’s arms.

According to Adalı, this is the first known Neo-Assyrian relief that includes Aramaic inscriptions and features Aramaean deities. It appears to reflect an early phase of the Assyrians’ presence in the area when the new arrivals accorded local belief systems respect in an attempt to win the favor of the populace. “The panel signals how the Neo-Assyrian Empire not only used military might but also tried to negotiate control by participating in various local rituals and adding their own tools to them,” says Adalı. By having his name included alongside portrayals of local deities, Mukın-abūa was likely trying to bolster his influence in the area. The outlines of the deities were incised to a depth of just a millimeter, and the most complete figure, of Hadad, includes only the upper portion of his body, suggesting that the panel was unfinished. “It’s possible that there was local unrest at the time,” says Adalı. “We do know that Mukın-abūa went to another part of the empire on behalf of the Assyrian king to suppress a rebellion. Perhaps something happened to him and he didn’t come back and this relief was left as it is.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024