Home | Category: Languages and Writing / Language and Hieroglyphics

PROTO WRITING

Engravings made by Neanderthals in a cave about 50,000 years ago

The earliest forms of human written and visual expression are paintings and drawing made by prehistoric man in caves and other places. Over time representations became less realistic and more stylized. A number of cultures produced these. Sometimes the representations were called “petrograms,” “petroglyphs” or “pictograms.” See Sahara Art, Hominids and Early Man

Stones with geometric designs, dated to around 10,000 B.C., found near the Mediterranean coast in Syria bore geometric engravings. Grooved stones with engraved plaquetts with a stylized representation of a scorpion and opened-winged bird and wavy lines perhaps representing water or serpents were found at Jerf el-Ahmar, an early village in northern Syria. The objects were dated to between 9600 and 8500 B.C. and are regarded as prototypes of writing.

Stone carvings, dated at around 8000 B.C., found in Syria contained small tablets recorded inventories of grain and animals. These were regarded as "more advanced than stone-age cave drawings but not as advanced as real writing."

The precursors to writing were crescent-shaped clay tokens with a few marks used in 4th millennium B.C. to count goods. Crescent-shaped clay taken unearthed in Iran are believed to have represented an ingot of metal while round tokens represented one sheep.

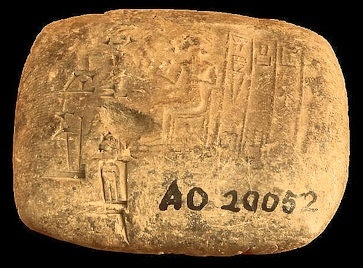

Before cuneiform writing was developed records were kept using clay figures sealed within round clay “envelopes.” In places were early writing developed there was a lot of mud and clay and reeds which could be used make lines and markings in the clay.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet” by J. T. Hooker (French) (1990) Amazon.com;

“The Story of Writing: Alphabets, Hieroglyphs & Pictograms” Illustrated by Andrew Robinson Amazon.com;

“Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East” by Amanda H Podany (2022) Amazon.com;

“The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process” (2024) by Stephen D. . Houston, Amazon.com;

“The First Signs: Unlocking the Mysteries of the World's Oldest Symbols”

by Genevieve von Petzinger Amazon.com

“History Begins at Sumer” by Samuel Noah Kramer (1956, 1988) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture” by Karen Radner and Eleanor Robson (2020) Amazon.com;

“Cuneiform Texts and the Writing of History” by Marc Van De Mieroop (1999) Amazon.com;

“Cuneiform” by Irving Finkel (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet” by Amalia Elisabeth Gnanadesikan (2009) Amazon.com;

“The World's Oldest Writings” by Henry James Reynolds Amazon.com;

“Writing and Literacy in Early China: Studies from the Columbia Early China Seminar Illustrated Edition” by Feng Li David Prager Amazon.com;

“The Origin of Chinese Characters: An Illustrated History and Word Guide”

by Kihoon Lee Amazon.com;

First Writing

The first widely recognized writing appeared around 3200 B.C. There is some debate as to whether it began in Mesopotamia or ancient Egypt. Most scholars say it began in Mesopotamia, where a system using abstract symbols evolved from pictographs in the 4th millennium.

In 1999, Gunter Dreyer of the German Archaeological Institute announced that they had discovered the world's oldest writing in Egypt not Mesopotamia. Recording linen and old deliveries in 3300 B.C. during the reign of a king from southern Egypt named Scorpion, the writing consists of hieroglyphic-like pictographs of animals, plants and mountains found on ivory tags in a royal tomb at Aydos. Some archaeologists regard the images as pictographs not true writing, but at least they could be accurately dated to between 3400 and 3200 B.C. using carbon dating.

Stories about a Scorpion king are found in ancient Egyptian literature. It was long thought that they were just myths but in recent years some evidence has appeared that has raised the possibility that the Scorpion King may have been a real person who played a critical role in establishing the ancient Egyptian civilization.

Economic Take of the Evolution of Writing in Mesopotamia

proto cuneiform from Sumer, daily salary

Arden Eby wrote in “Origin and Development of Writing in Mesopotamia: An Economic Interpretation”, “In 1927, A. Leo Oppenhime excavated the site of Nuzi in Iraq. He then reported finding a large number of tokens at various levels of the tell. In addition to these "tokens," he found an egg-shaped tablet that recorded the ownership of 48 animals; inside the egg were 48 tokens, suggesting a dual accounting system. Noticing these strange tokens, Schmandt began visiting Museums in the U.S., Europe and the near East to examine their small clay artifacts, noting their original locations and strata. Every museum and site she visited yielded these tokens — most were labeled "playthings," "games" or "amulets." Tokens of the same scheme were found from Beldibe in western Turkey to Chanu-Daro in eastern Iran. But the most important find was at a Neolithic site near Khartoum in Egypt. Evidently a single system of communication stretched from the 5th to the 4th Millennium B.C.! [Source: Arden Eby, “Origin and Development of Writing in Mesopotamia: An Economic Interpretation”, Internet Archive]

“These tokens, Schmandt found, were remarkably consistent until around 3100 B.C.. At that point, the development of a specialized farming economy and cities prompted the need for much more advanced forms of record keeping. Around the end of the fourth millennium B.C., egg-shaped envelopes, such as the one found at Nuzi, started to appear. The earliest of these contained only the name seal. But if a transaction was made, the seals had to be broken to display the contents. This problem was solved by impressing the tokens on the soft clay before sealing them inside the "egg," thus preserving both the envelope and the contents. Later the tokens themselves, being unnecessary, were dropped, but the signs remained to be incorporated into the script of the Uruk. Schmandt prepared another chart of the tokens closest to early Sumerian inscriptions: Notice that the token for the number "one" is exactly the same as the one used by Gelb to support his thesis.

“The common thread in both of these theories appears to be economic motivation. Arnold Toynbee's challenge-response theory suggests that it is the challenges of life in the desert that produced writing. Mesopotamia is a semi-arid plane. The only way for life to have existed there was to divert the rivers for irrigation — the digging of channels and dikes took organization. This organization, said Toynbee, led to an increase in specialization — it was more practical for one man to farm and another to build dikes. These conditions lent themselves, naturally, to the organization of trade, which, in turn necessitated a means of accounting18, or, as put by the French archaeologist Jean Claude Marguenon: ‘Born of economic necessity, the development of writing was due to the development of stock-farming within a social structure necessitating the presentation of accounts to owner who lived elsewhere. When accounts became too large to memorize, human ingenuity was challenged to find a substitute.’

“We have summarized the evidence employed by all the major archaeological theories concerning the origin of writing. Though they might disagree on the details, they all clearly suggest that this supremely important invention was motivated by economic necessity. One might suggest that the theories presented are merely unproven hypotheses however, one must admit that they are highly plausible (if not probable) hypotheses. It is left for new Gelbs, Schmandts and Margureons to unravel the additional details of the story of the invention of writing.”

Tokens, Precursor of Writing in Mesopotamia

Denise Schmandt-Besserat of the University of Texas wrote: “The direct antecedent of the Mesopotamian script was a recording device consisting of clay tokens of multiple shapes (Schmandt-Besserat 1996). The artifacts, mostly of geometric forms such as cones, spheres, disks, cylinders and ovoids, are recovered in archaeological sites dating 8000–3000 BC.. The tokens, used as counters to keep track of goods, were the earliest code—a system of signs for transmitting information. Each token shape was semantic, referring to a particular unit of merchandise. For example, a cone and a sphere stood respectively for a small and a large measure of grain, and ovoids represented jars of oil. The repertory of some three hundred types of counters made it feasible to manipulate and store information on multiple categories of goods (Schmandt-Besserat 1992). [Source: Denise Schmandt-Besserat, Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin, January 23, 2014 ]

clay accounting tokens from Susa in Elam in Iran

“The token system had little in common with spoken language except that, like a word, a token stood for one concept. Unlike speech, tokens were restricted to one type of information only, namely, real goods. Unlike spoken language, the token system made no use of syntax. That is to say, their meaning was independent of their placement order. Three cones and three ovoids, scattered in any way, were to be translated ‘three baskets of grain, three jars of oil.’ Furthermore, the fact that the same token shapes were used in a large area of the Near East, where many dialects would have been spoken, shows that the counters were not based on phonetics. Therefore, the goods they represented were expressed in multiple languages. The token system showed the number of units of merchandize in one-to-one correspondence, in other words, the number of tokens matched the number of units counted: x jars of oil were represented by x ovoids. Repeating ‘jar of oil’ x times in order to express plurality is unlike spoken language.”

On clay counters used in the Near East from about 9,000 B.C. to 1500 B.C., John Alan Halloran wrote in sumerian.org: “There were about 500 distinct types, although not in all times and places. Tokens start to be found at widely separated sites as of 8,000 B.C. (C-14), such as Level III of Tell Mureybet in Syria and Level E of Ganj Dareh in western Iran. Tokens were used at sites throughout the Near East, from Israel to Syria, Turkey, Iraq, and Iran, with the exception of Central Anatolia. The farthest extent of their use was from Khartoum in the Sudan to the pre-Harappan site of Mehrgahr in Pakistan. [Source: John Alan Halloran, sumerian.org, December 8, 1996 ==]

“The sounds of spoken language are also a system of standardized symbolic signs. However, one does find that the tokens were already in existence when the proto-Sumerians invented their simple consonant-vowel words, which include na4: 'pebble, stone; token'; na5: 'chest, box'; nu: 'image, likeness, picture, figurine, statue'. Note also ni; na: 'he, she; that one'; ní: 'self; body'; ia2,7,9, í: 'five'; ia4, i4: 'pebble, counter'; imi, im, em: 'clay'; eme: 'tongue; speech'. On the basis of this evidence, the implication that the tokens as a system for transmitting information preceded the system of spoken language appears to be correct.” ==

Tokens: their Significance for the Origin of Counting and Writing

Denise Schmandt-Besserat of the University of Texas wrote: ““Tokens were clay symbols of multiple shapes used to count, store and communicate economic data in oral preliterate cultures. (Schmandt-Besserat 1992, 1996, http://sites.utexas.edu/dsb) About 7500-3500 the code consisted of some 6 types such as cones, spheres, disks, cylinders, tetrahedrons and ovoids, each standing for one unit of a particular commodity. Most forms occurred in two distinct sizes, respectively about 1or 3 cm across, denoting quantity. These early types of geometric counters modeled in clay with an even surface, except for an occasional dot, are referred to as plain tokens. [Source: Denise Schmandt-Besserat, Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin, March 2, 2014 /~/]

“During the Urban Period, 3500-3100, new types of tokens appeared besides the plain ones. Among them were further geometric shapes such as quadrangles, triangles, paraboloids, ovals and biconoids, but also naturalistic forms including vessels, tools and animals. These so-called complex tokens were characteristically covered with lines or dots conferring qualitative information. Triangles, paraboloids, and mostly disks occurred in series bearing various sets of lines. Plain and complex tokens were found by the dozen or the hundreds in Near Eastern archaeological sites from Palestine to Anatolia and from Syria to Persia. After 3500, tokens were often perforated in order to be strung to a clay bulla. Others were kept in envelopes. These artifacts were hollow clay balls of spherical shape. Some of the envelopes displayed on the surface the impression of the tokens held inside. /~/

“1. Counting – Tokens shed light on the beginning of counting. First, the tokens were used in one-to-one correspondence: three jars of oil were shown by three ovoid tokens, which is the simplest way of reckoning. Second, the fact that each commodity was counted with a specific type of tokens, i.e. jars of oil could only be counted with ovoid tokens, denotes concrete counting. Concrete counting is characterized by different numerations or different sequences of number words to count different categories of items. /~/

“2. Economy – Tokens were linked to the economy. Their invention corresponds to the beginning of agriculture. For example, at Mureybet, Syria, tokens occur in level III, where pollen indicated the presence of cultivated fields. (Cauvin, 74) Second, the counters served exclusively to keep track of commodities. The plain tokens stood for farm products: small and large cones, spheres and flat disks stood for different measures of barley; ovoids for jars of oil; cylinders and lenticular disks represented numbers of domesticated animals and tetrahedrons for units of labor. /~/

Clay accounting tokens from Susa

“Ca. 3500, the proliferation of token shapes and markings reflected the multiplication of commodities manufactured in urban workshops. Triangular shapes stood for ingots of metal; series of disks bearing on their face various numbers of parallel lines stood for various qualities of textiles and paraboloids for garments. Quantities of beer, oil, honey were shown by tokens in the shape of their usual containers. There is no evidence that tokens were used for trade. Instead they were central to administration. /~/

“3. Administration – The mastery of counting and accounting with tokens fostered an elite based on administrative skills, who controlled the redistribution economy. The main function of tokens was to keep track of household and workshop contributions of surplus goods to the communal wealth and their redistribution for the support of the underprivileged or the organization of religious festivals. The bullae and envelopes with their multiple office seals illustrate the toughening of the city state administrations, when unpaid contributions were recorded until their settlement. /~/

“4. Cognition – Counting with tokens reflected the level of cognition of preliterate oral cultures. (Malafouris) Data processing with tokens was tactile. The counters were meant to be grasped and manipulated with the fingers. Addition, subtraction, multiplication and division of quantities of commodities were done by moving or removing counters by hand. /~/

“Tokens processed data concretely. First, the items counted consisted exclusively of goods, such as barley, animals and oil. Second, plurality was treated concretely, in one-to-one correspondence and with concrete numerations. /~/

“5. Writing – Tokens represent the first stage in the 9000-year continuous Near Eastern tradition of data processing. They led to writing. The change in communication that occurred on envelopes when the three-dimensional tokens were replaced by their two-dimensional impressions is considered the beginning of writing. Clay tablets bearing impressed signs replaced the tokens enclosed in envelopes. In turn, the impressed markings were followed by pictographs, or sketches of tokens and other items traced with a stylus. /~/

“Writing inherited from tokens a system for accounting goods, clay, and a repertory of signs. Writing brought abstraction to data processing: the signs abstracting tokens were no longer tangible; abstract numerals such as “1” “10” “60” replaced one-to-one correspondence; (fig.5) finally, pictographs took phonetic values. /~/

“6. Tokens Beyond the Near East – Plain tokens are not unique to the ancient Near East. Identical artifacts have been excavated in Central Asia at Jeitun, (Masson/Sarianidi, 35) in Western China at Shuangdun (Hang/ Qun/Li 130: 1-12; 133: 1-4 and 132: 1-12) and the Indus Valley at Mehrgarh (Jarrige/ Jarrige/Meadow/Quivron 361: 7.32 c). Similar clay counters in the same shapes and sizes are also reported in preliterate excavations outside of the Near Eastern sphere of influence in Europe (Budja), Africa (Addison 1, 214, 227, 241, 242; id. 2, 105: 11-13; 114: 6-11.) and Mesoamerica (Manzanilla 30, 2.8) suggesting that the tactile, concrete system of data processing corresponds to some fundamental aptitude of the human preliterate mind. However the phenomenon of complex tokens and the evolution into writing occurred only in the Near East /~/

“7. Significance – Tokens played a major role in the development of counting, data processing and communication in the ancient Near East. They made possible the establishment of a Neolithic redistribution economy and thereby set the foundation of the Mesopotamian Bronze Age civilization.” /~/

Pictography: Writing as Accounting Device

Chinese Shang Era writing on an oracle bone

Denise Schmandt-Besserat of the University of Texas wrote: “After four millennia, the token system led to writing. The transition from counters to script took place simultaneously in Sumer and Elam, present-day western Iran when, around 3500 BC, Elam was under Sumerian domination. It occurred when tokens, probably representing a debt, were stored in envelopes until payment. These envelopes made of clay in the shape of a hollow ball had the disadvantage of hiding the tokens held inside. Some accountants, therefore, impressed the tokens on the surface of the envelope before enclosing them inside, so that the shape and number of counters held inside could be verified at all times. These markings were the first signs of writing. The metamorphosis from three-dimensional artifacts to two-dimensional markings did not affect the semantic principle of the system. The significance of the markings on the outside of the envelopes was identical to that of the tokens held inside. [Source: Denise Schmandt-Besserat, Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin, January 23, 2014 ]

“About 3200 BC, once the system of impressed signs was understood, clay tablets—solid cushion-shaped clay artifacts bearing the impressions of tokens—replaced the envelopes filled with tokens. The impression of a cone and a sphere token, representing measures of grain, resulted respectively in a wedge and a circular marking which bore the same meaning as the tokens they signified. They were ideograms—signs representing one concept. The impressed tablets continued to be used exclusively to record quantities of goods received or disbursed. They still expressed plurality in one-to-one correspondence.

“Pictographs—signs representing tokens traced with a stylus rather than impressed—appeared about 3100 BC. These pictographs referring to goods mark an important step in the evolution of writing because they were never repeated in one-to-one correspondence to express numerosity. Besides them, numerals—signs representing plurality—indicated the quantity of units recorded. For example, ‘33 jars of oil’ were shown by the incised pictographic sign ‘jar of oil’, preceded by three impressed circles and three wedges, the numerals standing respectively for ‘10’ and ‘1’. The symbols for numerals were not new. They were the impressions of cones and spheres formerly representing measures of grain, which then had acquired a second, abstract, numerical meaning. The invention of numerals meant a considerable economy of signs since 33 jars of oil could be written with 7 rather then 33 markings.

“In sum, in its first phase, writing remained mostly a mere extension of the former token system. Although the tokens underwent formal transformations from three- to two-dimensional and from impressed markings to signs traced with a stylus, the symbolism remained fundamentally the same. Like the archaic counters, the tablets were used exclusively for accounting (Nissen and Heine 2009). This was also the case when a stylus, made of a reed with a triangular end, gave to the signs the wedge-shaped ‘cuneiform’ appearance. In all these instances, the medium changed in form but not in content. The only major departure from the token system consisted in the creation of two distinct types of signs: incised pictographs and impressed numerals. This combination of signs initiated the semantic division between the item counted and number.”

Logography: Shift from Visual to Aural

Denise Schmandt-Besserat of the University of Texas wrote: “About 3000 BC, the creation of phonetic signs—signs representing the sounds of speech—marks the second phase in the evolution of Mesopotamian writing, when, finally, the medium parted from its token antecedent in order to emulate spoken language. As a result, writing shifted from a conceptual framework of real goods to the world of speech sounds. It shifted from the visual to the aural world. [Source: Denise Schmandt-Besserat, Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin, January 23, 2014 ]

Sumerian writing from around 2600 BC

“With state formation, new regulations required that the names of the individuals who generated or received registered merchandise were entered on the tablets. The personal names were transcribed by the mean of logograms—signs representing a word in a particular tongue. Logograms were easily drawn pictures of words with a sound close to that desired (for example in English the name Neil could be written with a sign showing bent knees ‘kneel’). Because Sumerian was mostly a monosyllabic language, the logograms had a syllabic value. A syllable is a unit of spoken language consisting of one or more vowel sounds, alone, or with one or more consonants. When a name required several phonetic units, they were assembled in a rebus fashion. A typical Sumerian name ‘An Gives Life’ combined a star, the logogram for An, god of heaven, and an arrow, because the words for ‘arrow’ and ‘life’ were homonyms. The verb was not transcribed, but inferred, which was easy because the name was common.

“Phonetic signs allowed writing to break away from accounting. Inscriptions on stone seals or metal vessels deposited in tombs of the ‘Royal Cemetery’ of Ur, c. 2700–2600 BC, are among the first texts that did not deal with merchandise, did not include numerals and were entirely phonetic (Schmandt-Besserat 2007) The inscriptions consisted merely of a personal name: ‘Meskalamdug,’ or a name and a title: ‘Puabi, Queen’. Presumably, these funerary texts were meant to immortalize the name of the deceased, thereby, according to Sumerian creed, ensuring them of eternal life. Other funerary inscriptions further advanced the emancipation of writing. For example, statues depicting the features of an individual bore increasingly longer inscriptions. After the name and title of the deceased followed patronymics, the name of a temple or a god to whom the statue was dedicated, and in some cases, a plea for life after death, including a verb. These inscriptions introduced syntax, thus bringing writing yet one step closer to speech.

“After 2600–2500 BC, the Sumerian script became a complex system of ideograms mixed more and more frequently with phonetic signs. The resulting syllabary—system of phonetic signs expressing syllables—further modeled writing on to spoken language (Rogers 2005). With a repertory of about 400 signs, the script could express any topic of human endeavor. Some of the earliest syllabic texts were royal inscriptions, and religious, magic and literary texts.

“The second phase in the evolution of the Mesopotamian script, characterized by the creation of phonetic signs, not only resulted in the parting of writing from accounting, but also its spreading out of Sumer to neighboring regions. The first Egyptian inscriptions, dated to the late fourth millennium BC, belonged to royal tombs (Baines 2007). They consisted of ivory labels and ceremonial artifacts such as maces and palettes bearing personal names, written phonetically as a rebus, visibly imitating Sumer. For example, the Palette of Narmer bears hieroglyphs identifying the name and title of the Pharaoh, his attendants and the smitten enemies. Phonetic signs to transcribe personal names, therefore, created an avenue for writing to spread outside of Mesopotamia. This explains why the Egyptian script was instantaneously phonetic. It also explains why the Egyptians never borrowed Sumerian signs. Their repertory consisted of hieroglyphs representing items familiar in the Egyptian culture that evoked sounds in their own tongue.

“The phonetic transcription of personal names also played an important role in the dissemination of writing to the Indus Valley where, during a period of increased contact with Mesopotamia, c. 2500 BC, writing appears on seals featuring individuals’ names and titles (Parpola 1994). In turn, the Sumerian cuneiform syllabic script was adopted by many Near Eastern cultures who adapted it to their different linguistic families and in particular, Semitic (Akkadians and Eblaites); Indo-European (Mitanni, Hittites, and Persians); Caucasian (Hurrians and Urartians); and finally, Elamite and Kassite. It is likely that Linear A and B, the phonetic scripts of Crete and mainland Greece, c. 1400–1200 BC, were also influenced by the Near East. 4. The Alphabet: The Segmentation of Sounds

“The invention of the alphabet about 1500 BC ushered in the third phase in the evolution of writing in the ancient Near East (Sass 2005). The first, so-called Proto-Sinaitic or Proto-Canaanite alphabet, which originated in the region of present-day Lebanon, took advantage of the fact that the sounds of any language are few. It consisted of a set of 22 letters, each standing for a single sound of voice, which, combined in countless ways, allowed for an unprecedented flexibility for transcribing speech (Powell 2009). This earliest alphabet was a complete departure from the previous syllabaries. First, the system was based on acrophony—signs to represent the first letter of the word they stood for—for example an ox head (alpu) was ‘a,’ a house (betu) was b. Second, it was consonantal—it dealt only with speech sounds characterized by constriction or closure at one or more points in the breath channel, like b, d, l, m, n, p, etc. Third, it streamlined the system to 22 signs, instead of several hundred.

“The transition from cuneiform writing to the alphabet in the ancient Near East took place over several centuries. In the seventh century BC the Assyrian kings still dictated their edicts to two scribes. The first wrote Akkadian in cuneiform on a clay tablet; the second Aramaic in a cursive alphabetic script traced on a papyrus scroll. The Phoenician merchants established on the coast of present day Syria and Lebanon, played an important role in the diffusion of the alphabet. In particular, they brought their consonantal alphabetic system to Greece, perhaps as early as, or even before 800 BC. The Greeks perfected the Semitic alphabet by adding letters for vowels—speech sounds in the articulation of which the breath channel is not blocked, like a, e, i, o, u. As a result the 27-letter Greek alphabet improved the transcription of the spoken word, since all sounds were indicated. For example, words sharing the same consonants like ‘bad,’ ‘bed,’ ‘bid,’ ‘bud,’ could be clearly distinguished. The alphabet did not subsequently undergo any fundamental change.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024