Home | Category: Languages and Writing

SUMERIAN WRITING AND OTHER LANGUAGES

The Sumerian language endured in Mesopotamia for about a thousand years. The Akkadians, the Babylonians, Elbaites, Elamites, Hittites, Hurrians, Ugaritans, Persians and the other Mesopotamian and Near Eastern cultures that followed the Sumerians adapted Sumerian writing to their own languages.

Written Sumerian was adopted with relatively few modifications by the Babylonians and Assyrians. Other peoples such as Elamites, Hurrians, and Ugaritans felt that mastering the Sumerian system was too difficult and devised a simplified syllabary, eliminating many of the Sumerian word-signs.

Archaic Sumerian, the earliest written language in the world, remains as one of the written languages that have not been deciphered. Others include the Minoan language of Crete; the pre-Roman writing from the Iberian tribes of Spain; Sinaitic, believed to be a precursor of Hebrew; Futhark runes from Scandinavia; Elamite from Iran; the writing of Mohenjo-Dam, the ancient Indus River culture; and the earliest Egyptian hieroglyphics;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture” by Karen Radner and Eleanor Robson (2020) Amazon.com;

“Cuneiform Texts and the Writing of History” by Marc Van De Mieroop (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerian Language: An Introduction to Its History and Grammatical Structure” by Marie-Louise Thomsen (1984) Amazon.com;

“Sumerian Grammar” by Dietz Otto Edzard (2003) Amazon.com;

“Learn to Read Ancient Sumerian: An Introduction for Complete Beginners” by Joshua Aaron Bowen (2019) Amazon.com;

“A Manual of Sumerian Grammar and Texts” by John Hayes (1990) Amazon.com;

“A Brief Introduction to the Semitic Languages” by Aaron D. Rubin (2013) Amazon.com;

“Introduction to Akkadian” by Richard I. Caplice (1980) Amazon.com;

“Key to a Grammar of Akkadian” by John Huehnergard (1997) Amazon.com;

“An Akkadian Handbook: Paradigms, Helps, Glossary, Logograms, and Sign List” by R. Mark Shipp (1996) Amazon.com;

“Chaldean Grammar” by Mar Sarhad Y Jammo and Fr. Andrew Younan (2014) Amazon.com;

“Assyrian Primer: An Inductive Method of Learning the Cuneiform Characters” by John Dyneley Prince (1909) Amazon.com;

“Personal Names in Cuneiform Texts from Babylonia (c. 750-100 BCE): An Introduction” by 2024) Amazon.com;

“A History of Hittite Literacy: Writing and Reading in Late Bronze-Age Anatolia (1650-1200 BC)” by Theo van den Hout (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Elements of Hittite” by Theo van den Hout (2011) Amazon.com;

“A Grammar of the Hittite Language: Part 1: Reference Grammar” by Craig Melchert (2008) Amazon.com;

“Etymological Dictionary of the Hittite Inherited Lexicon” by Alwin Kloekhorst (2008) Amazon.com;

Sumerian Writing Spreads to the Akkadians

John Alan Halloran of sumerian.org wrote: “The fact that the Sumerians shared their land with Semitic-speaking Akkadians was important because the Akkadians had to turn the Sumerian logographic writing into phonetic syllabic writing in order to use cuneiform to represent phonetically the spoken words of the Akkadian language. [Source: John Alan Halloran, sumerian.org]

“Certain Sumerian cuneiform signs began to be used to represent phonetic syllables in order to write the unrelated Akkadian language, whose pronunciation is known from being a member of the Semitic language family. We have a lot of phonetically written Akkadian starting from the time of Sargon the Great (2300 B.C.). These phonetic syllable signs also occur as glosses indicating the pronunciation of Sumerian words in the lexical lists from the Old Babylonian period. This gives us the pronunciation of most Sumerian words. Admittedly the 20th century saw scholars revise their initial pronunciation of some signs and names, a situation that was not helped by the polyphony of many Sumerian ideographs. To the extent that Sumerian uses the same sounds as Semitic Akkadian, then, we know how Sumerian was pronounced. Some texts use syllabic spelling, instead of logograms, for Sumerian words. Words and names with unusual sounds that were in Sumerian but not in the Semitic Akkadian language can have variant spellings both in Akkadian texts and in texts written in other languages; these variants have given us clues to the nature of the non-Semitic sounds in Sumerian. [Ibid]

“In fact, bilingual Sumerian-Akkadian dictionaries and bilingual religious hymns are the most important source for arriving at the meaning of Sumerian words. But sometimes the scholar who studies enough tablets, such as the accounting tablets, learns in a more precise way to what a particular term refers, since the corresponding term in Akkadian may be very general.” The last known Akkadian cuneiform document dates from the first century AD. Neo-Mandaic spoken by the Mandaeans,

Elbaite Writing

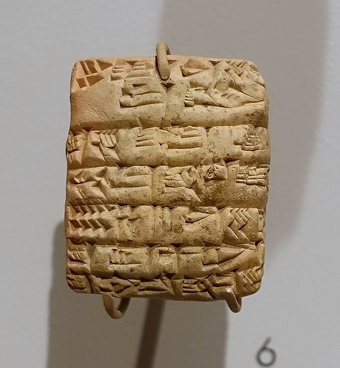

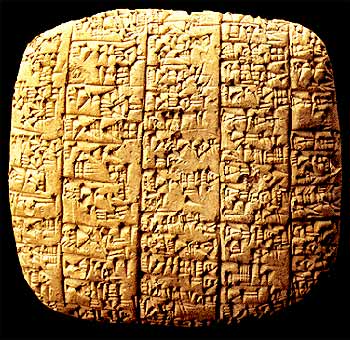

Ebla tablet A library with 17,000 clay tablets was discovered at Ebla in the 1960s. Most of tablets were inscribed with commercial records and chronicles like those found in Mesopotamia. Describing the importance of the tablets, Italian archaeologist Giovanni Pettinato told National Geographic, "Remember this: All the other texts of this period recovered to date are not total a forth of those from Ebla."

The tablets are mostly around 4,500 years old. They were written in the oldest Semitic language yet identified and deciphered with oldest know bilingual dictionary, written in Sumerian (a language already deciphered) and Elbaite. The Elbaites wrote in columns and used both sides of the tablets. Lists of figures were separated from the totals by a blank column. Treaties, description of wars and anthems to the gods were also recorded on tablets.

Ebla's writing is similar to that of the Sumerians, but Sumerian words are used to represent syllables in the Eblaite Semitic language. The tablets were difficult to translate because the scribes were bilingual and switched back and forth between Sumerian and the Elbaite language making it difficult for historians to figure which was which.

The oldest scribe academies outside of Sumer have been found in Ebla. Because the cuneiform script found on the Ebla tablets was so sophisticated, Pettinato said "one can only conclude that writing had been in use at Ebla for a long time before 2500 B.C."

Cuneiform tablets found in Ebla mention the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah and contain the name of David. They also mention Ab-ra-mu (Abraham), E-sa-um (Esau) and Sa-u-lum (Saul) as well as a knight named Ebrium who ruled around 2300 B.C. and bears an uncanny resemblance to Eber from the Book of Genesis who was the great-great grandson of Noah and the great-great-great-great grandfather of Abraham. Some scholars suggest that Biblical reference are overstated because the divine name yahweh (Jehovah) is not mentioned once in the tablets.

Very Old Babylonian and Assyrian Writing

The Kanesh tablets, which date to 1900 B.C. and were found in Turkey, reflect a time in which literacy was becoming widespread among Assyrian traders. According to Archaeology magazine: They used a type of relatively uncomplicated script, known as Old Assyrian cuneiform, characterized by simplified symbols that each represent a syllable or a whole word. Only around 120 distinct characters were used on the tablets found in Kanesh, which likely made it easier for people without formal schooling to learn on their own. “It’s very simple writing,” Assyriologist Cécile Michel of the French National Center for Scientific Research says. “Some of the letters I’m reading, they’re written so poorly, it tells me this person has just learned on the spot and figured out how to write.” [Source: Durrie Bouscaren, Archaeology magazine, November/December 2023]

At Sippar, a Babylonian site just south Baghdad, Iraqi archaeologists discovered an extensive library in the 1980s. A wide variety of tablets were found, including ones that contained literary works, dictionaries, prayers, omens, incantations, astronomical records — still arranged on shelves.

Deciphering Sumerian, Old Persian, Babylonian and Assyrian

Samuel Noah Kramar deciphered the Sumerian cuneiform tablets in the 19th century using Rosetta-Stone-like bilingual texts with the same passages in Sumerian and Akkadian (Akkadian in turn had been translated using Rosetta-Stone-like bilingual texts with some passages in an Akkadian-like language and Old Persian). The most important texts came from Persepolis, the ancient capital of Persia.

After the Akkadian text was deciphered, words and sounds in a hitherto unknown language, which appeared to be older and unrelated to Akkadian, were found. This led to the discovery of the Sumerian language and the Sumerian people.

Babylonian and Assyrian were deciphered after Old Persian was deciphered. Old Persian was deciphered in 1802, by George Grotefend, a German philologist. He figured out that one of the unknown languages represented by the cuneiform writing from Persepolis was Old Persian based on the words for Persian kings and then translated the phonetic value of each symbol. Early linguists decided that cuneiform was most likely an alphabet because 22 major signs appeared again and again.

Akkadian and Babylonian were deciphered between 1835 and 1847, by Henry Rawlinson, a British military officer, using the Behistun Rock (Bisotoun Rock). Located 20 miles from Kermanshah, Iran, it is one of the most important archeological sites in the world. Located at an elevation of 4000 feet high on an ancient highway between Mesopotamia and Persia, it is a cliff face carved with cuneiform characters that describe the achievements of Darius the Great in three languages: Old Persian, Babylonian and Elamatic.

Rawlinson copied the Old Persian text while suspended by a rope in front of the cliff.. After spending several years working out all Old Persian texts he returned and translated the Babylonian and Elamitic sections. Akkadian was worked out because it was a Semitic similar to Elamitic.

The Behistun Rock also allowed Rawlinson to decipher Babylonian. Assyrian and the entire cuneiform language was worked with the discovery of Assyrian “instruction manuals” and “dictionaries” found at a 7th century Assyrian site.

Ugaritic letters

Ugarites and Their Early Alphabet

According to the Guinness Book of Records, the earliest example of alphabetic writing was a clay tablet with 32 cuneiform letters found in Ugarit, Syria and dated to 1450 B.C. The Ugarits condensed the Eblaite writing, with its hundreds of symbols, into a concise 30-letter alphabet that was the precursor of the Phoenician alphabet.

The Ugarites reduced all symbols with multiple consonant sounds to signs with a single consent sound. In the Ugarite system each sign consisted of one consonant plus any vowel. That the sign for “p” could be “pa,” “pi” or “pu.” Ugarit was passed on to the Semitic tribes of the Middle east, which included the Phoenician, Hebrews and later the Arabs.

Ugarit, an important 14th century B.C. Mediterranean port on the Syrian coast, was the next great Canaanite city to arise after Ebla. Tablets found at Ugarit indicated it was involved in the trade of box and juniper wood, olive oil, wine.

Ugarit texts refer to deities such as El, Asherah, Baak and Dagan, previously known only from the Bible and a handful of other texts. Ugarit literature is full of epic stories about gods and goddesses. This form of religion was revived by the early Hebrew prophets. An 11-inch-high silver-and-gold statuette of a god, circa 1900 B.C., unearthed at Ugarit in present-day Syria.

See Separate Article: UGARIT: ITS EARLY ALPHABET, GODS, TRADE AND THE BIBLE africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024