Home | Category: Themes, Early History, Archaeology

RULERS AND DYNASTIES OF ANCIENT EGYPT

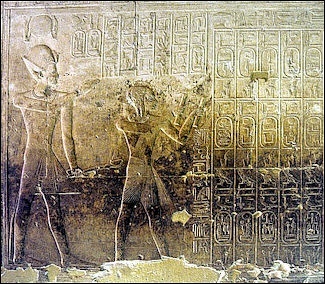

Abydos Kings List

Lists of kings ( pharaohs) were compiled for temple records in antiquity and are a major source for the Pharaonic history of Egypt. In the 3rd century B.C. the Egyptian priest Manetho used older king lists to write a history of Egypt in Greek for the new Ptolemaic rulers, and his work was quoted by Greek and Latin historians such as Josephus. Manetho is responsible for dividing Egyptian history into 30 dynasties from the initial unification of the country to its conquest by Alexander the Great (332 B.C.), a model followed by modern scholars. The chronology of Pharaonic Egypt is, for the most part, well established, although some uncertainties persist. [Source: New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003]

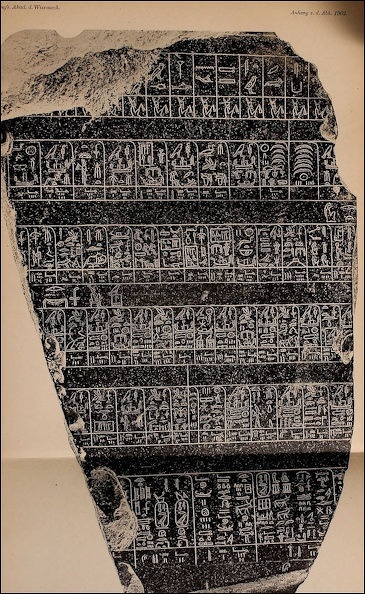

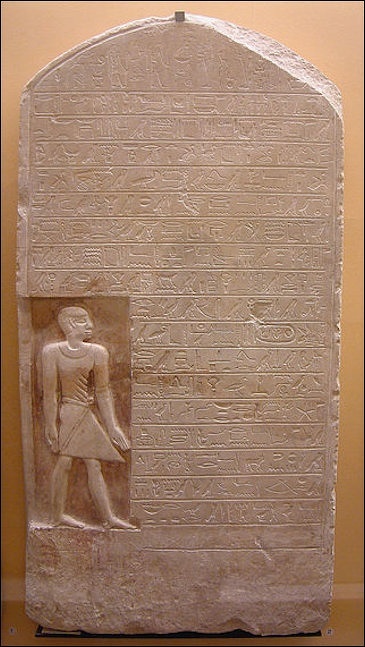

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Our knowledge of the succession of Egyptian kings is based on kinglists kept by the ancient Egyptians themselves. The most famous are the Palermo Stone, which covers the period from the earliest dynasties to the middle of Dynasty 5; the Abydos Kinglist, which Seti I had carved on his temple at Abydos; and the Turin Canon, a papyrus that covers the period from the earliest dynasties to the reign of Ramesses II. All are incomplete or fragmentary. We also rely on the History of Egypt written by Manetho, a priest in the temple at Heliopolis, Manetho had access to many original sources and it was he who divided the kings into the thirty dynasties we use today. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org\^/]

“It is to this structure of dynasties and listed kings that we now attempt to link an absolute chronology of dates in terms of our own calendrical system. The process is made difficult by the fragmentary condition of the kinglists and by differences in the calendrical years used at various times. Some astronomical observations from the ancient Egyptians have survived, allowing us to calculate absolute dates within a margin of error. Synchronisms with the other civilizations of the ancient world are also of limited use.” \^/

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: Although Manetho's original book did not survive, we know of it from the works of later historians such as Josephus, who lived around AD 70 and quoted Manetho in his own works. Although Manetho’s history was based on native Egyptian sources and mythology, it is still used by Egyptologists to confirm the succession of kings when the archaeological evidence is inconclusive. Events were recorded by the reigns of kings and not, as in our dating system, based on a commonly agreed calendar system. For that reason, exact dating of events in Egyptian history is unreliable. [Source:Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Early Dynastic Egypt” by Toby A.H. Wilkinson (2001) Amazon.com;

“A History of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2: From the Great Pyramid to the Fall of the Middle Kingdom” by John Romer (2012) Amazon.com;

“Manetho: History of Egypt and Other Works” by Manetho Amazon.com;

”Ancient Egypt: Foundations of a Civilization” by Douglas J. Brewer (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume I: From the Beginnings to Old Kingdom Egypt and the Dynasty of Akkad” by Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, D. T. Potts, Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com; Wilkinson is a fellow of Clare College at Cambridge University;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt:The Definitive Visual History” by Steven R. Snape (2021) Amazon.com;

Oldest Kings Lists of Ancient Egypt

According to National Geographic History: While there are several “kings lists” that record the names of pharaohs and their successors, intact ones that extend all the way back to that Early Dynastic era are few. Two of the most important were found in the 1980s by researchers from the German Archaeological Institute in Cairo. They uncovered two cylinder seal impressions in the tomb of the pharaoh Den. These seals—still the oldest documented king lists to date—list rulers and successors of the 1st dynasty. One seal dates to the middle of the 1st dynasty and names six rulers. The other seal dates closer to the end of the 1st dynasty and names eight leaders. Both lists begin with Narmer. [Source: National Geographic, National Geographic, June 10, 2022]

Royal lists created millennia later, during the New Kingdom, have created the confusion. One of the most complete is the Abydos King List, engraved upon the wall of the mortuary temple of Seti I (13th century B.C.). Engraved on the wall, Seti and his heir, Ramses (the future Ramses II), face rows of cartouches bearing the names of Egypt’s past pharaohs. On this list, however, the first king listed is Menes, not Narmer.

The Turin Papyrus is another king list from the same era as Seti I. Rather than being engraved in stone, it is cursive hieratic script written on papyrus and is one of the most accurate and complete king lists, covering the 1st through the 19th dynasties. It, too, names the first king as Menes and not Narmer. Writing centuries later, classical authors, such as the fifth-century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus, wrote of Menes rather than Narmer as the unifier of Egypt. A third-century B.C. priest in the temple at Heliopolis, Manetho, was an author of another trusted source that also lists Menes as the first king.

Egyptologists tried to reconcile the use of these two names. Perhaps they were two different people, one who unified Egypt and another who ruled after him. Or Menes could have been a composite figure, cobbled together from the lives and deeds of other early kings. English Egyptologist Flinders Petrie came up with the most widely accepted theory: Narmer and Menes were the same person. Narmer was the name of the first pharaoh of the 1st dynasty, and Menes was an honorific title, meaning “he who endures.”

Periods of Ancient Egyptian History

Neolithic flint knives

1) The history of the Ancient Egyptians can be divided into seven periods that correspond to the major dynastic ages of Pharaonic history:

1) Predynastic – (prehistory)

2) Early Dynastic Period (Archaic) – Dyn. 1–3, 2920–2575 B.C.

3) Old Kingdom – Dyn. 4–8 (Pyramid Age), 2575–2134 B.C.

4) First Intermediate Period – Dyn. 9–10, 2134–2040 B.C.

5) Middle Kingdom – Dyn. 11–12 ("Classical" Period), 2040–1640 B.C.

6) Second Intermediate Period – Dyn. 13–17 (including the Hyksos Period), 1640–1532 B.C.

7) New Kingdom – Dyn. 18–20 (Empire Period), 1550–1070 B.C.

[Source: Encyclopaedia Judaica, Thomson Gale, 2007]

The history of Ancient Egypt is sometimes divided into six periods:

Old Kingdom (2649–2150 B.C.)

Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.)

New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.)

Late Period (712–332 B.C.)

Ptolemaic Period (304–30 B.C.)

Roman Period (30 B.C.–364 A.D.)

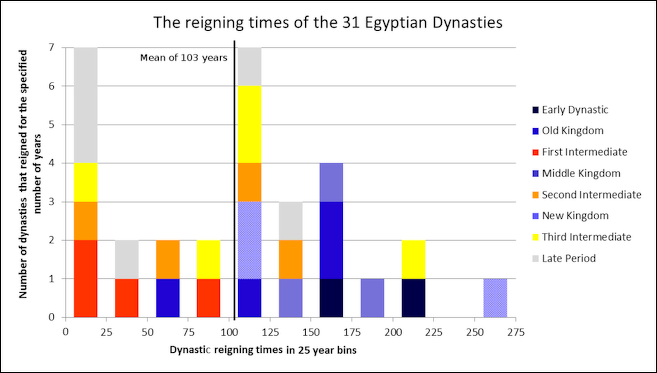

"The 'dynasties' of Egypt are really just retrospective constructs," Michael Dee, an associate professor of isotope chronology at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, told Live Science. It wasn't until around 300 B.C. that writers started to divide Egypt into dynasties, Dee said. While many pharaohs within a dynasty have a direct family relationship, not all do. "Dynasties are successive members of the same family with some additions," Marc Van De Mieroop, a history professor at Columbia University, told Live Science. "They were made up by Manetho." The 18th dynasty of Egypt, which started around 1550 B.C. and lasted around 250 years, is the longest ancient Egyptian dynasty. According to Live Science: Scientists estimate the length of the 18th dynasty by analyzing written records and radiocarbon dates. And although the 18th dynasty was the longest of the dynasties delineated by Manetho, the periods of Greek and Roman rule were longer, Van De Mieroop said. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, April 16, 2023]

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: The ancient Egyptians listed their kings in a continuous sequence beginning with the reign on earth of the sun god, Ra. Modern scholars have divided Manetho’s thirty dynasties into “Kingdoms.” During certain times, kingship was divided or the political and social conditions were chaotic, and these eras are called “Intermediate Periods.” Today the generally agreed chronology is divided as follows, beginning from 3100 B.C.: The Archaic Period (414 years), The Old Kingdom (505 years), The First Intermediate Period (126 years), The Middle Kingdom (405 years), The Second Intermediate Period (100 years), The New Kingdom (481 years), The Third Intermediate Period (322 years), The Late Period (415 years), The Ptolemaic Period (302 years).” [Source:Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

Pre-Dynastic Ages and Cultures of Ancient Egypt

Prehistoric Era

Lower Paleolithic Age (250,000-90,000 B.C.)

Middle Paleolithic Age (90,000-30,000 B.C.

Late Paleolithic Age (30,000 B.C.)-7000 B.C.)

Neolithic Age (7000-4800 B.C.)

Predynastic Period (4800-3050 B.C.)

Upper Egypt

Badarian Culture (4800-4200 B.C.)

Amratian Culture (4200-3700 B.C.)

Gerzean A Culture (3700-3250 B.C.)

Gerzean B Culture (3250-3050 B.C.)

Lower Egypt

Fayum A Culture (4800-4250 B.C.)

Merimde Culture (4500-3500 B.C.)

Archaic Period (3100-050-2705 B.C.)

According to Live Science: Dynasties one and two date back around 5,000 years and are often called the "Early Dynastic" or "Archaic" period. The first pharaoh of the first dynasty was a ruler named Menes (or Narmer, as he is called in Greek). He lived over 5,000 years ago, and while ancient writers sometimes credited him as being the first pharaoh of a united Egypt, however archaeological research suggests that this is not true. Recently found inscriptions tell of rulers — such as Djer and Iry-Hor — who appear to have ruled earlier and other finds have been made which suggest that there were pharaohs before Menes who ruled a united Egypt. Scholars sometimes refer to these pre-Menes rulers as being part of a "dynasty zero." [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

Old Kingdom 2649–2150 B.C.

Dynasties three to six, dating from roughly 2650 to 2150 B.C., are often grouped together into a time period called the "Old Kingdom". According to Live Science: During this time pyramid-building techniques were developed and the pyramids of Giza were built. Papyri that are still being deciphered suggest that groups of professional workers — sometimes translated as "work gangs" — played a major role in the construction of the pyramids, as well as other structures. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

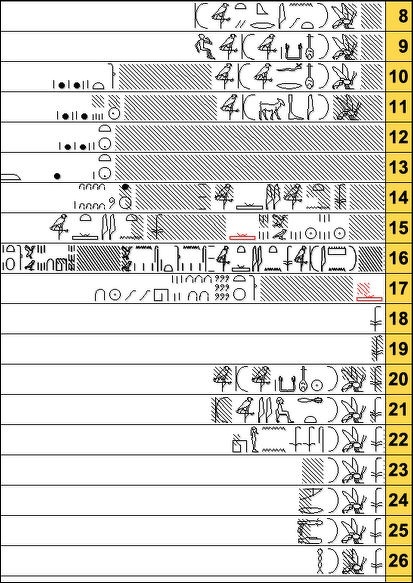

Turin King List 4

Old Kingdom

(ca.2649–2150 B.C.)

Dynasty 3, (ca. 2649–2575 B.C.)

Zanakht (ca. 2649–2630 B.C.)

Djoser (ca. 2630–2611 B.C.)

Sekhemkhet (ca. 2611–2605 B.C.)

Khaba (ca. 2605–2599 B.C.)

Huni (ca. 2599–2575 B.C.)

[Source: Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002]

Dynasty 4, (ca. 2575–2465 B.C.)

Snefru (ca. 2575–2551 B.C.)

Khufu (ca. 2551–2528 B.C.)

Djedefre (ca. 2528–2520 B.C.)

Khafre1 (ca. 2520–2494 B.C.:

Nebka II (ca. 2494–2490 B.C.)

Menkaure2 (ca. 2490–2472 B.C.)

Shepseskaf (ca. 2472–2467 B.C.)

Thamphthis (ca. 2467–2465 B.C.)

Dynasty 5, (ca. 2465–2323 B.C.)

Userkaf (ca. 2465–2458 B.C.)

Sahure (ca. 2458–2446 B.C.:

Neferirkare (ca. 2446–2438 B.C.)

Shepseskare (ca. 2438–2431 B.C.)

Neferefre (ca. 2431–2420 B.C.)

Niuserre (ca. 2420–2389 B.C.)

Menkauhor (ca. 2389–2381 B.C.)

Isesi (ca. 2381–2353 B.C.)

Unis (ca. 2353–2323 B.C.)

Dynasty 6, (ca. 2323–2150 B.C.)

Teti (ca. 2323–2291 B.C.)

Userkare (ca. 2291–2289 B.C.)

Pepi I (ca. 2289–2255 B.C.)

Merenre I (ca. 2255–2246 B.C.)

Pepi II (ca. 2246–2152 B.C.)

Merenre II (ca. 2152–2152 B.C.)

Netjerkare Siptah (ca. 2152–2150 B.C.)

See Separate Articles under OLD AND MIDDLE KINGDOM (AGE OF THE PYRAMIDS) africame.factsanddetails.com

Great Dynasties of the Old Kingdom

Dr Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol wrote: “1st Dynasty: Egypt was unified around 3000 B.C., when the kings of the south of the country absorbed their northern neighbours into a single state, with a newly-founded capital in the north, at Memphis (about 20km-12 miles-south of modern Cairo). It was after this event, during the first two dynasties, that the ground-rules of Egyptian society were laid and the hieroglyphic script developed. The kings of the 1st Dynasty were buried in the heart of the old southern kingdom, at Abydos, in brick-lined tombs out in the desert, with an offering place flanked by stelae bearing their names. Perhaps the finest is the one shown here, of King Djet. This was found in 1898, and is now in the Louvre in Paris. [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, Egyptologist,University of Bristol, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“3rd Dynasty: During the first dynasties, architecture was largely based on mud-brick and organic material, and it was not until Djoser came to the throne around 2700 B.C. that the first large-scale building in stone took place. The first of these structures was in the form of the Step Pyramid at Saqqara, shown here. It was designed by the chancellor Imhotep, who was later worshipped as a god of medicine. |The Step Pyramid and the buildings surrounding it owe much to the forms previously created with traditional materials, but are entirely rendered in stone. As the oldest major stone building in the world, this pyramid remains a pivotal monument. The history of the dynasty itself is little known, with even the names and succession of its kings still debated by Egyptologists. |::|

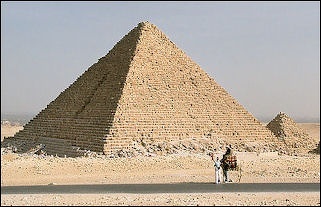

“4th Dynasty: The pyramids at Giza, on the outskirts of modern Cairo, are perhaps the most iconic of all Egyptian monuments, and they mark the high point in the engineering skills first displayed by Imhotep in the previous dynasty. The largest, the Great Pyramid, shown here furthest from the camera, remains the most massive freestanding monument ever raised by humankind. |The 4th Dynasty was the period at which many of the institutions of the state appeared in mature form, and the art of this dynasty became firmly established in the canons that would endure until the end of Egyptian civilisation. |::|

“5th Dynasty: The end of the 4th Dynasty marked the close of the era of great pyramids. Henceforth rather smaller and less well built pyramids would be the norm, such as the one shown here, of Sahure at Abu Sir (c.2450 B.C.). In contrast, the temples that adjoined the pyramids, dedicated to the posthumous wellbeing of the dead pharaoh, were greatly increased in size and splendour, being adorned with beautifully carved reliefs on the walls, and paved with exotic stones.” |::|

Middle Kingdom and Intermediate Periods (2150-1540 B.C.)

According to Live Science: From 2150 to 2030 B.C. (a time period that encompassed dynasties seven to 10 and part of 11) the central government in Egypt was weak and the country was often controlled by different regional leaders. Why the Old Kingdom collapsed is a matter of debate among scholars, with research indicating that drought and climate change played a significant role. During this time, cities and civilizations in the Middle East also collapsed, with evidence at archaeological sites indicating that a period of drought and arid climate hit sites across the region. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

The 12th, 13th and part of the 11th dynasties are often called the "Middle Kingdom" by scholars and lasted from around 2030 to 1640 B.C. At the start of this dynasty, a ruler named Mentuhotep II (who reigned until about 2000 B.C.) regained control of the whole country. Pyramid building resumed in Egypt, and a sizable number of texts of literature and science were created. Among the surviving texts is a document now known as the Edwin Smith surgical papyrus, which records a variety of medical treatments that modern-day medical doctors have hailed as being advanced for their time.

Dynasties 14 to 17 are often grouped together as the "Second Intermediate Period" by modern-day scholars. During this time, the central government again collapsed in Egypt, and a group called the "Hyksos" rose to power, controlling much of northern Egypt. While the Hyksos may have originally been from the Levant (an area that encompasses modern-day Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Jordan and Syria), research indicates that they were already in Egypt at the time the government collapsed. One gruesome find from this time period is a series of severed hands, which were found at a palace at the city of Avaris, the capital of Hyksos-controlled Egypt. The severed hands may have been presented by soldiers to a ruler in exchange for gold.

Turin List 8

First Intermediate Period

(ca. 2150–2030 B.C.)

Dynasty 8–Dynasty 10, (ca. 2150–2030 B.C.)

Dynasty 11, first half, (ca. 2124–2030 B.C.)

Mentuhotep I (ca. 2124–2120 B.C.)

Intef I (ca. 2120–2108 B.C.)

Intef III (ca. 2059–2051 B.C.)

Mentuhotep II (ca. 2051–2030 B.C.)

[Source: Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002]

Middle Kingdom

(ca. 2030–1640 B.C.)

Dynasty 11, second half, (ca. 2030–1981 B.C.)

Mentuhotep II (cont.) (ca. 2030–2000 B.C.)

Mentuhotep III (ca. 2000–1988 B.C.)

Qakare Intef (ca. 1985 B.C.)

Sekhentibre (ca. 1985 B.C.)

Menekhkare (ca. 1985 B.C.)

Mentuhotep IV (ca. 1988–1981 B.C.)

Dynasty 12, (ca. 1981–1802 B.C.)

Senusret I7 (ca. 1961–1917 B.C.)

Amenemhat II (ca. 1919–1885 B.C.)

Senusret II (ca. 1887–1878 B.C.)

Senusret III (ca. 1878–1840 B.C.)

Amenemhat III (ca. 1859–1813 B.C.)

Amenemhat IV (ca. 1814–1805 B.C.)

Dynasty 13, (ca. 1802–1640 B.C.)

Second Intermediate Period

(ca. 1640–1540 B.C.)

Dynasty 14–Dynasty 16, (ca. 1640–1635 B.C.)

Dynasty 17, (ca. 1635–1550 B.C.)

Tao I (ca. 1560 B.C.)

Tao II (ca. 1560 B.C.)

Kamose (ca. 1552–1550 B.C.)

See Separate Articles under OLD AND MIDDLE KINGDOM (AGE OF THE PYRAMIDS) africame.factsanddetails.com

Great Dynasties of the Middle Kingdom

Dr Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol wrote: “11th Dynasty: After around 2190 B.C., Egypt fell to pieces, the various provinces eventually coalescing around the cities of Thebes and Herakleopolis. The resulting civil war was won by the Thebans of the 11th Dynasty, led by King Mentuhotep II. He kept the capital in the south, and there he built the tomb shown above, at a site now called Deir el-Bahari. It was a terraced temple of an unusual form, perhaps once topped by a pyramid. The burial chamber was at the end of a long tunnel beginning in the courtyard at the rear of the temple. [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, Egyptologist, University of Bristol, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“12th Dynasty: The new line of pharaohs moved the capital back north from Thebes and resumed the building of pyramids for their tombs. The 12th Dynasty was one of great prosperity, which also re-established Egyptian control of Nubia, an area that straddled what is today the border of Egypt and Sudan. It was an important source of raw materials-especially gold-and was a crucial conduit of trade from central Afri(ca. |Another thriving area during the period was the Fayum, an oasis area 100km (62 miles) south of Cairo, which saw major irrigation and other public works. Amongst these were two king's pyramids, one of them being the monument shown here, of Amenemhat III at Hawara. Unusually, it was built of mud-brick rather than stone, and it had a gargantuan temple built on the south side. This temple, known as the 'Labyrinth', was destroyed 2,000 years ago, leaving only the fragments visible in the foreground.” |::|

New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.)

Dynasties 18 to 20 encompass the "New Kingdom," which lasted around 1550 to 1070 B.C. This period took place after the Hyksos had been defeated by a series of Egyptian rulers and the country reunited. According to Live Science: Perhaps the most famous archaeological site from the New Kingdom is the Valley of the Kings, which holds the burial sites of many Egyptian rulers from this period, including Tutankhamun (reign circa 1336 to 1327 B.C.), whose rich tomb was found intact in1922. The pharaohs stopped building pyramids during the New Kingdom for a variety of reasons — one of which was to provide better security against tomb robbers. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

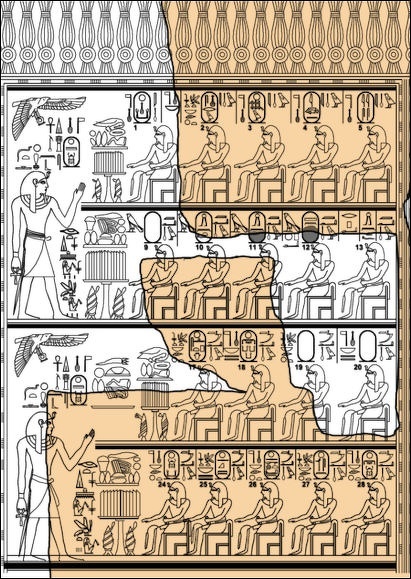

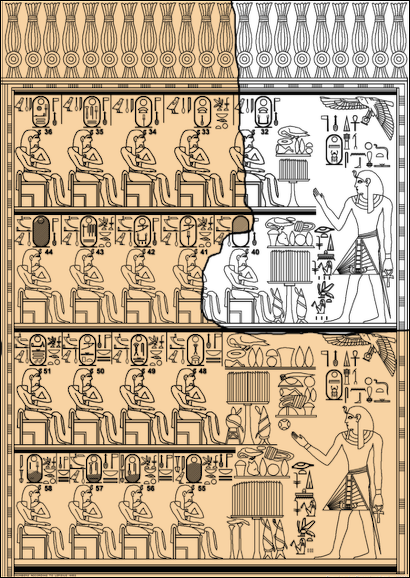

Karnak King List drawing 1

New Kingdom

(ca.1550–1070 B.C.)

Dynasty 18, (ca. 1550–1295 B.C.)

Ahmose11 (ca. 1550–1525 B.C.)

Amenhotep I (ca. 1525–1504 B.C.)

Thutmose II (ca. 1504–1492 B.C.)

Thutmose II (ca. 1492–1479 B.C.)

Thutmose III (ca. 1479–1425 B.C.)

Hatshepsut (as regent) (ca. 1479–1473 B.C.)

Hatshepsut15 (ca. 1473–1458 B.C.)

Amenhotep II (ca. 1427–1400 B.C.)

Thutmose IV (ca. 1400–1390 B.C.)

Amenhotep III (ca. 1390–1352 B.C.)

Amenhotep IV (ca. 1353–1349 B.C.)

Akhenaten (ca. 1349–1336 B.C.)

Neferneferuaton (ca. 1338–1336 B.C.)

Smenkhkare (ca. 1336 B.C.)

Tutankhamun (ca. 1336–1327 B.C.)

Aya (ca. 1327–1323 B.C.)

Haremhab (ca. 1323–1295 B.C.)

[Source: Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002]

Dynasty 19, (ca. 1295–1186 B.C.)

Ramesses I (ca. 1295–1294 B.C.)

Seti I (ca.1294–1279 B.C.)

Ramesses II (ca. 1279–1213 B.C.)

Merneptah (ca. 1213–1203 B.C.)

Amenmesse (ca. 1203–1200 B.C.)

Seti II (ca. 1200–1194 B.C.)

Siptah (ca. 1194–1188 B.C.)

Tawosret (ca. 1188–1186 B.C.)

Karnak King List Drawing 3

Dynasty 20, (ca. 1186–1070 B.C.)

Sethnakht (ca. 1186–1184 B.C.)

Ramesses III (ca. 1184–1153 B.C.)

Ramesses IV (ca. 1153–1147 B.C.)

Ramesses V (ca. 1147–1143 B.C.)

Ramesses VI (ca. 1143–1136 B.C.)

Ramesses VII (ca. 1136–1129 B.C.)

Ramesses VIII (ca. 1129–1126 B.C.)

Ramesses IX (ca. 1126–1108 B.C.)

Ramesses X (ca. 1108–1099 B.C.)

Ramesses XI (ca. 1099–1070 B.C.)

Hight Priests (HP) of Amun (ca. 1080–1070 B.C.)

HP Herihor (ca. 1080–1074 B.C.)

HP Paiankh (ca. 1074–1070 B.C.)

See Separate Articles under NEW KINGDOM (KING TUT, RAMSES, HATSHEPSUT) africame.factsanddetails.com

Great Dynasties of the New Kingdom

Dr Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol wrote: “18th Dynasty: Perhaps the height of Egyptian wealth and power came between 1550 and 1290 B.C. The dynasty began with the expulsion of the Palestinian Hyksos rulers from the north of Egypt by King Ahmose I-an event that may have inspired the Biblical story of the Exodus. Carrying forward the momentum of this act, subsequent rulers, in particular Thutmose III, established an empire of client states in Syria-Palestine, and dominions stretching towards the heart of Afri(ca. War booty and lively international trade founded on Egypt's highly productive gold mines made Egypt a major world player. [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, Egyptologist, University of Bristol, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Around 1350 B.C., however, King Akhenaten (formerly known as Amenhotep IV-see above) turned Egypt on its head by abolishing all the nation's gods, and replacing them with a single sun-god, the Aten. The new faith was accompanied by a radical new art-style, as seen in the statuette above, currently owned by the Louvre. The cult of Aten, however, barely survived the death of its patron. Within a few years, orthodoxy had been re-established and Akhenaten's very dynasty had died out, leaving the throne to a series of generals, the last of whom, Ramesses I, was the founder of a new 19th Dynasty. |::|

“19th Dynasty: After the upheavals of the late 18th Dynasty, the new royal house combined a return to traditional values with a number of innovations. Tradition is seen in the building of temples to the ancient gods and the repair of monuments damaged during the iconoclastic Akhenaten's reign, and also in an aggressive foreign policy. Under Ramesses II (1279-1212 B.C.), this culminated in the great battle against the Hittites at Qadesh in Syria. The long-term strategic stalemate that followed the battle, however, resulted in a peace treaty in 1258 that left the two powers the best of friends for the rest of the century. |::|

“Meanwhile, innovation was seen in the prominence granted to depictions of members of the royal family in public monuments, a practice that perhaps reached its peak at Abu Simbel, where the dominant figure in the smaller of the two temples seen here (on the right) was not the pharaoh, but Queen Nefertiry (not to be confused with the earlier Queen Nefertiti). However, the dynasty ended in chaos, with rebellion within the royal house, culminating in the end of the dynasty amid civil war.” |::|

Third Intermediate Period 1070–713 B.C.)

According to Live Science: The 21st to 24th dynasties (a period from around 1070 to 713 B.C.) are often called the "Third Intermediate Period" by modern-day scholars. The central government was sometimes weak during this time period, and the country was not always united. During this time cities and civilizations across the Middle East had been destroyed by people from the Aegean, whom modern-day scholars sometimes call the "Sea Peoples." While Egyptian rulers claimed to have defeated the Sea Peoples in battle, it didn't prevent Egyptian civilization from collapsing. The loss of trade routes and revenue may have played a role in the weakening of Egypt's central government. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

Palermo Stone

Third Intermediate Period

(ca.1070–713 B.C.)

Dynasty 21, (ca. 1070–945 B.C.)

Smendes (ca. 1070–1044 B.C.)

HP Painedjem I (ca. 1070–1032 B.C.)

HP Masaharta (ca. 1054–1046 B.C.)

HP Djedkhonsefankh (ca. 1046–1045 B.C.)

HP Menkheperre (ca. 1045–992 B.C.)

Amenemnisu (ca. 1044–1040 B.C.)

Psusennes I (ca. 1040–992 B.C.)

Amenemope (ca. 993–984 B.C.)

HP Smendes (ca. 992–990 B.C.)

HP Painedjem II (ca. 990–969 B.C.)

Osochor (ca. 984–978 B.C.)

Siamun (ca. 978–959 B.C.)

HP Psusennes (ca. 969–959 B.C.)

Psusennes II (ca. 959–945 B.C.)

[Source: Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002]

Dynasty 22 (Libyan), (ca. 945–712 B.C.)

Sheshonq I (ca. 945–924 B.C.)

Osorkon I (ca. 924–889 B.C.)

Sheshonq II (ca. 890 B.C.)

Takelot I (ca. 889–874 B.C.)

Osorkon II (ca. 874–850 B.C.)

Harsiese (ca. 865 B.C.)

Takelot II (ca. 850–825 B.C.)

Sheshonq III (ca. 825–773 B.C.)

Pami (ca. 773–767 B.C.)

Sheshonq V (ca. 767–730 B.C.)

Osorkon IV (ca. 730–712 B.C.)

Dynasty 23, (ca. 818–713 B.C.)

Pedubaste I (ca. 818–793 B.C.)

Iuput I (ca. 800 B.C.)

Sheshonq IV (ca. 793–787 B.C.)

Osorkon III (ca. 787–759 B.C.)

Takelot III (ca. 764–757 B.C.)

Rudamun (ca. 757–754 B.C.)

Iuput II (ca. 754–712 B.C.)

Peftjaubast (ca. 740–725 B.C.)

Namlot (ca. 740 B.C.)

Thutemhat (ca. 720 B.C.)

Dynasty 24, (ca. 724–712 B.C.)

Tefnakht (ca. 724–717 B.C.)

Bakenrenef (ca. 717–712 B.C.)

Late Period (712–332 B.C.)

Dynasties 25 to 31 (from around 712 to 332 B.C.) are often referred to as the "Late Period". Egypt was sometimes under the control of foreign powers during this time. The rulers of the 25th dynasty were from Nubia, an area located in modern-day southern Egypt and northern Sudan. The Persians and Assyrians also controlled Egypt at different times during the Late Period. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

Late Period

(ca. 712–332 B.C.)

Dynasty 25 (Nubian), (ca. 712–664 B.C.)

Shebitqo31 (ca. 698–690 B.C.)

Taharqo (Loses control of Lower Egypt)32 (ca. 690–664 B.C.)

Tanutamani (Loses control of Upper Egypt) (ca. 664–653 B.C.)

[Source: Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002]

Dynasty 26 (Saite) (688–252 B.C.)

Nikauba (688–672 B.C.)

Necho I (672–664 B.C.)

Psamtik I33 (664–610 B.C.)

Necho II (610–595 B.C.)

Psamtik II (595–589 B.C.)

Apries34 (589–570 B.C.)

Amasis35 (570–526 B.C.)

Psamtik III (526–525 B.C.)

Dynasty 27 (Persian), 525–404 B.C.)

Cambyses (525–522 B.C.)

Darius I (521–486 B.C.)

Xerxes I (486–466 B.C.)

Artaxerxes I (465–424 B.C.)

Darius II (424–404 B.C.)

Dynasty 28, 522–399 B.C.)

Pedubaste III (522–520 B.C.)

Psamtik IV (ca. 470 B.C.)

Inaros (ca. 460 B.C.)

Amyrtaios I (ca. 460 B.C.)

Thannyros (ca. 445 B.C.)

Pausiris (ca. 445 B.C.)

Psamtik V (ca. 445 B.C.)

Psamtik VI (ca. 400 B.C.)

Amyrtaios II (404–399 B.C.)

Dynasty 29, 399–380 B.C.)

Nepherites I (399–393 B.C.)

Psammuthis (393–393 B.C.)

Achoris (393–380 B.C.)

Nepherites II (380–380 B.C.)

Dynasty 30, 380–343 B.C.)

Nectanebo I (380–362 B.C.)

Teos (365–360 B.C.)

Nectanebo II36 (360–343 B.C.

Persians (343–332 B.C.)

Khabebesh (343–332 B.C.)

Artaxerxes III Ochus (343–338 B.C.)

Arses (338–336 B.C.)

Darius III Codoman (335–332 B.C.)

See Separate Articles under LATE DYNASTIES, PERSIANS, NUBIANS, PTOLEMIES, CLEOPATRA, GREEKS AND ROMANS africame.factsanddetails.com

Great Dynasties of the Late and Third Intermediates Periods

Dr Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol wrote: “21st Dynasty: Around 1070 B.C., Egypt was in decline, losing its Nubian provinces and other sources of revenue. A new royal family began to rule from Tanis in the far north-east, but the south was ruled by a largely independent series of High Priests at Thebes. |Amenemopet was one of the Tanite kings of the 21st Dynasty. His mummy was found in the tomb of his predecessor, Psusennes I, at Tanis in 1939, adorned with the gold mask illustrated above. Although superficially impressive, the gold is very thin, only covering the front of the head, in contrast with the thick helmet-mask of the 18th-Dynasty pharaoh Tutankhamun. [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, Egyptologist, University of Bristol, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“22nd Dynasty: Libyans had settled in Egypt from the 18th Dynasty onwards, and became well established in the north-west, with their own traditional leaders or chieftains. Some of these leaders married into Egyptian ruling families, and finally, around 975 B.C., a member of one of these Libyo-Egyptian families became pharaoh. |Bearing such Libyan names as Shoshenq, Osorkon and Takelot, a series of these Libyo-Egyptian kings comprised the 22nd and 23rd dynasties. Initially, major efforts were made to restore Egypt's internal unity and international standing, and Shoshenq I undertook military campaigns into Palestine. Osorkon I, whose statue, shown above, can be seen in the Louvre Museum in Paris, was engaged in diplomatic efforts in the same area. However, internal conflicts developed once more, and by 840 B.C. the country was irrevocably split in two. |::|

“25th Dynasty: For much of Egyptian history, Nubia had been regarded merely as a source of manpower and minerals for the Egyptian state. Then, around 730 B.C., tables were turned, and the Nubian King Piye invaded and conquered Egypt. The king and his successors were, however, steeped in Egyptian culture, and viewed themselves as the renewers of ancient glories, rather than as foreign incomers. As such, they revived the ancient custom of pyramid building, which had been dropped by the pharaohs some eight centuries before-shown above are the ruins of the pyramid of Taharqa (690-664 B.C.). Despite this history, Taharqa's successor was soon driven out of Egypt by an Assyrian invasion, never to return. |::|

“26th Dynasty: After their invasion, the Assyrians soon withdrew from Egypt, leaving power in the hands of Psametik I (664-610 B.C.), ruler of the city of Sais in north-western Egypt. His dynasty followed that of the Nubians in its promotion of the past as a model for the present, much of its artwork being inspired by, or copied from, ancient models. |::| Unfortunately, although the Assyrians were no longer a threat, the Persians took over Egypt in the reign of Psametik III, shown above on a relief in a chapel in the temple of Karnak. This take-over spelt the beginning of the end for Egypt as an independent nation.” |::|

Ptolemaic Period: Greeks and Romans After Alexander the Great

According to Live Science: In 332 B.C. Alexander the Great drove the Persians out of Egypt and incorporated the country into the Macedonian Empire. After Alexander the Great's death, a line of rulers descended from Ptolemy Soter, one of Alexander's generals, came to power. The last of these "Ptolemaic" rulers (as scholars often call them) was Cleopatra VII, who died by suicide in 30 B.C. after the defeat of her forces by Octavian, who would later be named the Roman emperor Augustus, at the Battle of Actium. After her death, Egypt was incorporated into the Roman Empire. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

Although the Roman emperors were based in Rome, the Egyptians treated them as pharaohs. One excavated carving shows the emperor Claudius (reign A.D. 41 to 54) dressed as a pharaoh, Live Science reported. The carving has hieroglyphic inscriptions saying that Claudius is the "Son of Ra, Lord of the Crowns," and "King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Lord of the Two Lands." Neither the Ptolemaic or Roman rulers are considered to be part of a numbered dynasty.

Macedonian Period (332–304 B.C.)

Alexander the Great (332–323 B.C.)

Philip Arrhidaeus (323–316 B.C.)

Alexander IV (316–304 B.C.)

[Source (Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002]

Ptolemaic Period ( 304–30 B.C.)

Ptolemy I Soter I (304–284 B.C.)

Ptolemy II Philadelphos (285–246 B.C.

Arsinoe II (278–270 B.C.)

Ptolemy III Euergetes I (246–221 B.C.)

Berenike II (246–221 B.C.)

Ptolemy IV Philopator (222–205 B.C.)

Ptolemy V Epiphanes (205–180 B.C.)

Harwennefer (205–199 B.C.)

Ankhwennefer (199–186 B.C.)

Cleopatra I (194–176 B.C.)

Ptolemy VI Philometor (180–145 B.C.)

Cleopatra II (175–115 B.C.)

Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II (170–116 B.C.)

Harsiese ((ca. 130 B.C.)

Ptolemy VII Neos Philopator (145–144 B.C.)

Cleopatra III (142–101 B.C.)

Ptolemy IX Soter II (116–80 B.C.)

Ptolemy X Alexander I (107–88 B.C.)

Ptolemy XI Alexander II (80–80 B.C.)

Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos (80–51 B.C.)

Cleopatra IV Berenike III ((ca. 79 B.C.)

Berenike IV (58–55 B.C.)

Ptolemy XIII (51–47 B.C.)

Cleopatra VII (51–30 B.C.)

Ptolemy XIV (47–44 B.C.)

Ptolemy XV (44–30 B.C.)

Roman Period (30 B.C.–364 A.D.)

Augustus (30–14 B.C.)

Byzantine Period

364–476 A.D.

See Separate Articles under LATE DYNASTIES, PERSIANS, NUBIANS, PTOLEMIES, CLEOPATRA, GREEKS AND ROMANS africame.factsanddetails.com

List of Rulers of Ancient Sudan

Napatan Dynasty

Alara (Unites Upper Nubia) (785–760 B.C.)

Kashta (Unites all Nubia) (760–747 B.C.)

Piye (Rules Nubia and Egypt) (747–712 B.C.)

Shabaqo(1) (712–698 B.C.)

Shebitqo(2) (698–690 B.C.)

Taharqo (Loses control of Lower Egypt)(3) (690–664 B.C.)

Tanwetamani (Loses control of Upper Egypt) (664–653 B.C.)

Atlanersa (653–643 B.C.)

Senkamanisken (643–623 B.C.)

Anlaman (623–593 B.C.)

Aspelta (593–568 B.C.)

Irike–Amanote (425–400 B.C.)

Harsiyotf (400–365 B.C.)

Nastasen (320–310 B.C.)

Meroitic Dynasty

(ca. 275 B.C.–300 A.D.

Arkamani (275–250 B.C.)

Arnekhamani (225–175 B.C.)

Adikhalamani

Arkamani II

Kandake (Queen) Shanakdakheto (170–150 B.C.)

Taneyidamani (100–75 B.C.)

Teriteqas (50–1 B.C.)

Kandake Amanitore

Kandake Amanishakheto

Natakamani (1–50 A.D.)

Kandake Amanitore

Shorkaro

[Source (Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2001, metmuseum.org]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024