Home | Category: Themes, Early History, Archaeology

ANCIENT EGYPT

Ancient Egypt is arguably the world’s most favorite ancient civilization. Coming into existence around 3050 B.C., when Upper and Lower Egypt, were united, its appeal lies in the fact that it is so old, so strange yet so familiar. The Greeks and Romans may have produced wonderful vase art and classical statuary and laid the foundation for western civilization with their ideas about democracy, jurisprudence and philosophy but the Egyptians produced the pyramids, the Sphinx and colorful works of art preserved for thousands of years in the dry desert air. Their rulers married their siblings and hired embalmers to suck out the brains of the dead through their nose while ordinary Egyptian folks wore black eyeliner and make up, ate bread, garlic and onions and drank beer.

Ancient Egypt is arguably the world’s most favorite ancient civilization. Coming into existence around 3050 B.C., when Upper and Lower Egypt, were united, its appeal lies in the fact that it is so old, so strange yet so familiar. The Greeks and Romans may have produced wonderful vase art and classical statuary and laid the foundation for western civilization with their ideas about democracy, jurisprudence and philosophy but the Egyptians produced the pyramids, the Sphinx and colorful works of art preserved for thousands of years in the dry desert air. Their rulers married their siblings and hired embalmers to suck out the brains of the dead through their nose while ordinary Egyptian folks wore black eyeliner and make up, ate bread, garlic and onions and drank beer.

Ancient Egypt was one of the most powerful and influential civilizations in the ancient world. Leaving behind many monuments, works of art and documents and that continue to be studied by scholars today, it existed region for over 3,000 years, from around 3100 B.C. to 30 B.C. However Egyptian civilization existed long before this times and long afterwards. While its rulers, language, writing, religion and borders have changed many times over the millennia, Egypt still exists as a modern-day country. Ancient Egypt was linked with other parts of the Mediterranean and Near East — and even parts of Asia — through trade and the exchange of people and ideas. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

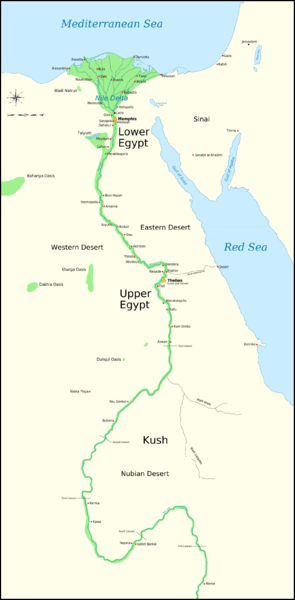

The name Egypt means “Two Lands,” reflecting the two separate kingdoms of Upper and Lower prehistoric Egypt – Delta region in the north and a long length of sandstone and limestone in the south. In 3000 B.C., a single ruler, Menes, unified the entire land and set the stage for an impressive civilization that lasted 3,000 years. He began with the construction of basins to contain the flood water, digging canals and irrigation ditches to reclaim the marshy land. [Source: Plumbing & Mechanical Magazine, July 1989, theplumber.com]

According to the Columbia Encyclopedia:“The valley of the "long river between the deserts," with the annual floods, deposits of life-giving silt, and year-long growing season, was the seat of one of the earliest civilizations built by humankind. The antiquity of this civilization is almost staggering, and whereas the history of other lands is measured in centuries, that of ancient Egypt is measured in millennia. Much is known of the period even before the actual historic records began. Those records are abundant and, because of Egypt's dry climate, have been well preserved. Inscriptions have unlocked a wealth of information; for example, the existing fragments of the Palermo stone are engraved with the records of the kings of the first five dynasties. The great papyrus dumps offer an enormous amount of information, especially on the later periods of ancient Egyptian history. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw (1995) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com; Wilkinson is a fellow of Clare College at Cambridge University;

“Atlas of Ancient Egypt” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

“Manetho: History of Egypt and Other Works” by Manetho Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: An Illustrated Reference to the Myths, Religions, Pyramids and Temples of the Land of the Pharaohs” by Lorna Oakes (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” (DK Eyewitness Books) by George Hart (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization” by Barry Kemp (1989, 2018) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“Temples, Tombs, and Hieroglyphs: A Popular History of Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz (1978, 2009) Amazon.com;

“Egypt” (Insiders) by Joyce Tyldesley (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Egyptian” by Mika Waltari (1945) Novel Amazon.com;

“River God” by Wilbur Smith (1993) Novel Amazon.com;

“Daughter of the Gods: A Novel of Ancient Egypt” by Stephanie Marie Thornton (2014) Amazon.com;

“Emerald Tablets of Thoth the Atlantean” by Maurice Doreal (1930) Novel Amazon.com;

“I, the Sun” by Janet Morris (1983) Novel Amazon.com;

Features of Ancient Egypt

It is not known exactly what ancient Egyptians looked like: whether they were white, black or brown. Many scholars believe they probably looked like modern Egyptians. Many of the famous Egyptian names were originally Greeks food names. Pyramids is thought to have been derived from the Greek name for little honey cakes. Obelisk is the Greek word for meat skewers.

The Nile flooded between June and August each year, and the fertile soil it created was vital to ancient Egypt's survival, with fertility playing an important role in Egyptian religion. Fertility was an important concept in Ancient Egypt and featured prominently in the rituals and beliefs of the ancient Egyptians. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

Modern Egyptians have many of the customs as their ancient ancestors. Flax is still harvested by hand by pulling the grass-like plants up from the roots; bricks are still made from silt mixed with straw, shaped into blocks and baked in the sun; women still supplicant themselves to the dead; alabaster bowls are still shaped and polished with a drill weighted by stones and twisted by hand; men still tell folk tales while recreating a battle with a stick dance; barley is still threshed by oxen going round and round with a sled over a pile of stalks and women winnow the grain by tossing it into the wind.

A number of names have been ascribed to for Egypt. A popular ancient name for Egypt was "Kemet," which means the "black land." Scholars generally believe that this name derived from the fertile soil that was left over when the Nile flood receded in August. At times ancient Egypt ruled territory outside the modern-day country's border, controlling territory in what is now Sudan, Cyprus, Lebanon, Syria, Israel and Palestine. The country was also occupied by other powers in ancient times — the Persians, Nubians, Greeks and Romans all conquered Egypt at different points. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

The Egyptian empire didn’t embrace all that much physical territory. It followed the Nile like a snake in present-day Egyptians and northern Sudan and included the Nile delta but didn’t stretch very far beyond the Nile. One reason the Egyptian civilization endured as well as did was because the Nile is sheltered by near-impenetrable deserts to both the east and the west. The only way to really approach it is from the Mediterranean Sea, where defenses could be concentrated for protection against foreign incursions. In addition to that the Egyptians didn’t stir up much trouble: they didn’t venture far from their come territory and didn’t seem that interested in conquering others.

Historical Sources and Periods of Ancient Egypt

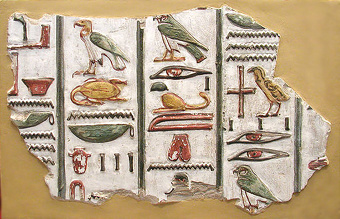

Knowledge about ancient Egypt has been collected from hieroglyphics in tombs, on buildings and in ancient texts; descriptions by ancient historians such as the 5th century B.C. Greek, Herodotus; and archaeological excavations.

The lists of kings and dynasties is based on the tablet of Abydos — which contains the names of Egyptian kings from Menes (the first great pharaoh) to Seti I and was found in a necropolis near the Nile town of Abyos — and the “ Aegyptiaca” , a historical text written in the 3rd century B.C. by a Egyptian priest named Manetho. The “ Aegyptiaca” was more complete but it survived only in secondary pieces by classical era historians. Manetho used older king lists to write a history of Egypt in Greek for the new Ptolemaic rulers. His work was quoted by Greek and Latin historians such as Josephus. Manetho is responsible for dividing Egyptian history into 30 dynasties from the initial unification of the country to its conquest by Alexander the Great (332 B.C.), a model followed by modern scholars. The chronology of Pharaonic Egypt is, for the most part, well established, although some uncertainties persist. [Source: New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003]

Pharonic Egyptian history is divided into for four periods: 1) Early Dynastic Egypt (3,200-2700 B.C.); 2) the Old Kingdom (2700-2155 B.C.); 3) the Middle Kingdom (2134-1785 B.C.); 4) the New Kingdom (1,580 to 1085 B.C.). Historians have given the name "kingdom" to those periods in Egyptian history when the central government was strong, the country was unified, and there was an orderly succession of pharaohs. At times, however, central authority broke down, competing centers of power emerged, and the country was plunged into civil war or was occupied by foreigners. These periods are known as "intermediate periods." [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

After 1085 B.C. Egypt was divided and ruled by priests. Egyptian culture went into a period of decline during this era and. Egypt was conquered the Persians in 525 B.C. After experiencing a brief period of autonomy it was conquered again by Alexander the Great in 332 B.C. When Alexander died his kingdom was divided into two: one of generals, Ptolemy took over Egypt. His descendants ruled Egypt until the death of Cleopatra in the first century A.D.

When Did Ancient Egypt Begin?

How old is ancient Egypt? It depends how you define it, Aidan Dodson, an Egyptology professor at the University of Bristol in the U.K. told Live Science. "If you take it as meaning the civilization that incorporated pharaonic kingship, the language that was written in hieroglyphs, and the religion that was finally replaced by Christianity, it began around 3100 B.C., and ended around A.D. 400" Dodson told Live Science. Kathryn Bard, a professor emerita of archaeology and classical studies at Boston University, offered a similar date. "The pharaonic state began ca. 3,000 [B.C.]," she said. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, October 6, 2022

However, humans were living in Egypt long before 3000 B.C. The "oldest known human presence in the Nile Valley is estimated to be some 400,000 years ago. Agriculture in Egypt dates back to about 5000 B.C. By 4100 B.C., permanent year-round agricultural villages had been established in parts of Egypt, Katary wrote. Some year-round settlements eventually grew into cities. Naqada and Hierakonpolis became important urban centers between 3500 B.C. and 3000 B.C.,

Around 3100 B.C., Egypt unified under a pharaoh, and a writing system, often called hieroglyphs, was established. The Egyptian priest Manetho — who lived millennia later, around the third century B.C. — reported that the first ruler of united Egypt was a king named Menes, but modern-day scholars debate the exact identity of Menes and the accuracy of Manetho's claim.

Dating Ancient Egypt

Dating of ancient Egypt is usually done based on king lists, the ruling dates of the pharaohs and the ancient Egyptian civil calendar with evidence from archaeological work thrown in. The estimates have often been uncertain because each dynasty often established new dates.

There is a lot of confusion over dates. Each museum and scholar seems to have its own set of dates. Some set the Old Kingdom at 2700 to 2150 B.C.; others set it at 2686 to 2181 B.C.; and others still at 2700 to 2200 B.C. According to one scholar, "Although royal registers exist the length of each king's reign and even the exact number of sovereigns, are still debated."

According to the Columbia Encyclopedia:“Among the many problems encountered in Egyptology, one of the most controversial is that of dating events. Dates have a margin of plus or minus 100 years for the time prior to 3000 B.C. Fairly precise dates are possible beginning with the Persian conquest (525 B.C.) of Egypt. The division of Egyptian history into 30 dynasties up to the time of Alexander the Great (a system worked out by Manetho) is a convenient frame upon which to hang the succession of the kings and a record of events. There are many gaps and periods without well-known rulers (occasionally without known rulers at all). [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Relatively New Archaeologically-Based Dating of Ancient Egypt

In a June 2010 article in journal Science, a team led by Oxford University professor Christopher Ramsey said that it had come up with best set of dates yet based on carbon dating the remains of plants, seeds, baskets, textiles, plant stems and fruit obtained from museums in the United States and Europe. “For the first time, radio carbon dating has become precise enough to constrain the history of ancient Egypt to very specific dates,” Ramsey said.

Sindya N. Bhanoo wrote in the New York Times in 2010, “A new study provides detailed information about the timeline of ancient Egypt’s Old, Middle and New Kingdoms using radiocarbon dating.Although much is known about the chronological order of the pharaohs who ruled ancient Egypt, the dates have remained fuzzy. By dating 211 plant samples from artifacts associated with the reigns of different kings, the study gives the most precise information to date on dozens of pharaohs. It appears in the June 18 issue of Science.” [Source: Sindya N. Bhanoo, New York Times, June 21, 2010]

1450 B.C.

For instance, the New Kingdom — the era of King Tutankhamun and the Kings Rameses — began between 1570 and 1544 B.C., according to the report. Previous estimates suggested the date was 1550 or 1539 B.C. The data also indicates that Djoser, a notable pharaoh of the Old Kingdom, started his reign between 2691 and 2625 B.C. Previous estimates have varied considerably, with two widely cited sources suggesting his reign started in 2667 or 2592 B.C.

“The research agrees with the previous estimates but gives us more precise windows,” Christopher Bronk Ramsey, an archaeologist at the University of Oxford, told the New York Times. To conduct the study, Dr. Ramsey and his colleagues used samples from museums around the world. The samples came from seeds, baskets, textiles, plant stems and fruits associated with a particular reign. Most of the samples had been taken out of tombs.Previous radiocarbon dating used technology that was less precise, and coal and wood samples, which may have led to inaccurate estimates. Because resources like coal and wood were in short supply, they may have been reused over the course of different reigns, Dr. Ramsey said. In the new study, he and his colleagues focused on plant materials because of their short lifespan.

Upper and Lower Egypt and the Cycles of the Nile

Upper Egypt refers to southern Egypt, specifically to the Nile Valley south of the Nile Delta. Lower Egypt refers to northern Egypt, usually the Nile Delta. The regions are so named because Upper Egypt was located along the upriver section of the Nile and Lower Egypt was situated on the down river section of the Nile.

Throughout its history, Egypt has been characterized by a rivalry between Lower Egypt and Upper Egypt. Many tomb and temple paintings and inscriptions feature pharaohs wearing either: 1) an Upper Egypt crown (a large, white, conehead-type headdress); 2) a Lower Egypt crown (a red headdress that looks bottle stopper with a spike rising from the back); or 3) an Upper and Lower Egypt crown (a combination of the two aforementioned crowns). The later symbolized the unification of the two regions.

The concept of two lands did not disappear when Upper and Lower Egypt were united around 3100 B.C. According to National Geographic: Rather, the dual nature of the Egyptian kingdom was emphasized, as duality was an important tenet of Egyptian culture, including the throne itself. Later 1st dynasty pharaohs would embrace the title “Ruler of the Two Lands,” and following pharaohs would continue to use the title through the ages. Keeping the identities of the two lands distinct from each other was a way of giving the new political order a divine sanction. Central to ancient Egyptian belief were two opposite and necessary forces—ma’at (order) and isfet (chaos), the static and dynamic forces that govern the universe. Balance was desired, and order and chaos must coexist in order for equilibrium to be achieved. [Source: National Geographic, National Geographic, June 10, 2022]

Instead of being oriented towards progress, ancient Egyptian society was built around symmetry and the rhythms of nature — especially in regards to the yearly flooding of the Nile. Herodotus defined Egyptians as those who drank from the Nile and the Egyptians themselves believed there had to be a Nile in the sky since there was one on Earth.

The fortunes of Egypt often rose and feel with the level of the Nile. When the river was low during droughts, crops couldn’t grow as a result of lack of water. When the river was high during floods, fields were swamped and crops died as a result of too much water. The floods also brought rich river sediments that fertilized the soil and water that could be stored and used later in irrigation.

Egyptian Achievements

Greek historian Herodotus wrote in the 5th century B.C., the Egyptians, "first brought into use the names of twelve gods, which the Greeks adopted from them; and first erected altars, images, and temples to the gods; and also who first engraved upon stone the figures of the animals."

The Old Kingdom formed a central state with a national bureaucracy that supervised construction of canals, monuments and the pyramids (2700 BC). During the first dynasty of the Old Kingdom great advances were made in architecture, painting, sculpture, mass transportation, distribution of food, and sanitation. Their traditions were continued with few alterations by the dynasties that followed.

Although the ancient Egyptians had no word for “art” they revered beauty and produced architecture, reliefs, paintings, murals, statues, decorative arts, and a variety of crafts. They also produced the pyramid s, hieroglyphics and extraordinary temples with massive columns and statues. So many splendid works of Egyptian art have come down to us today because they were made of durable materials like stone and clay and the hot desert air of Egypt has been ideal for preserving them. Most objects were excavated from the tombs of kings, queens and nobility.

Unchanging Egypt

Egyptian culture remained virtually unchanged during the long reign of the pharaohs. "For three thousand years," historian Daniel Boorstin wrote in “The Creators”, "their sculpture showed less change than modern European sculpture in a decade. And their pharaohs of the Third Dynasty (2980-2900 B.C.,) still appear to the layman's eye virtually in the same style as their pharaohs of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty (663-525 B.C.).”

Expressing the same thought in a different way, historian John Keegan wrote in the “History of Warfare” the Egyptians "maintained a stable almost unvarying way of life, based on the three seasons of inundation, growing and drought, for almost 2500 years, a same span of time between the Golden Age of Greece to the landing of a man on the moon." By contrast the Roman empire lasted only around 700 years. Only China ranks with ancient Egypt in terms of longevity but it went through many cataclysmic changes and lacked the continuity of Egypt.

“If regularity ruled the world" of the ancient Egyptians, Boorstin wrote, "unique events were unreal or insignificant. And if the unique had no meaning, what meaning could there be in history? Since the past was never remote, theirs was a timeless world. Since the same event occurred again and again, their texts could describe the whole past as if it where the present."

Ancient Egyptians continued to make mummies at least until 220 B.C. Egypt-based Coptic Christians continued the tradition many centuries after the birth of Christ. Worshippers gathered a temple, honoring the Egyptian god Isis, on the island of Philae until it was closed in the sixth century A.D.

Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt

In a review of “The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson, Michiko Kakutani wrote in the New York Times, “Wilkinson’s new book, sheds light on patterns in Egyptian history and the ways in which the country’s geography (which made it susceptible to invasion and attack) and “the sharp dichotomies of nature in the Nile Valley” (flood and drought, fertile land and arid desert) amplified what Mr. Wilkinson sees as a national proclivity to view “the world as a constant battle between order and chaos” — a tendency that he says the country’s leaders often played upon to justify their domineering, autocratic rule.[Source: Michiko Kakutani, New York Times March 28, 2011]

After studying ancient Egypt for more than 20 years Mr. Wilkinson says he found himself growing “increasingly uneasy about the subject of my research” — increasingly aware of “the darker side of pharaonic civilization,” which has often been glossed over, he says, by the “misty-eyed reverence” that many scholars have shared with tourists. “We marvel at the pyramids,” he writes, “without stopping to think too much about the political system that made them possible. We take vicarious pleasure in the pharaohs’ military victories — Thutmose III at the Battle of Megiddo, Ramesses II at the Battle of Kadesh — without pausing too long to reflect on the brutality of warfare in the ancient world. We thrill at the weirdness of the heretic king Akhenaten and all his works, but do not question what it is like to live under a despotic, fanatical ruler.”

Mr. Wilkinson argued in his Wall Street Journal essay that Egyptian history has a “depressing habit of repeating itself.” In much the same way that the Old Kingdom ended in fragmentation and civil war, so did despotism in the Middle Kingdom give way to weakness and confusion that left the country vulnerable to invasion. A band of Theban loyalists would succeed against all odds in expelling these foreigners known as the Hyksos, and Egypt would reassert itself as a great imperial power, controlling a territory that stretched more than 2,000 miles. But the glorious era of the New Kingdom too would come to an end with the rise of other powers in the region, including Assyria, Persia, Greece and Rome.

“The last act of Egypt’s great drama,” Mr. Wilkinson observes, “was played out in the streets of Alexandria with a cast of characters as famous as any: Caesar, Mark Antony, and Cleopatra. With her death, in 30, Egypt became a Roman possession and its 3,000-year-old pharaonic tradition came to an end.”

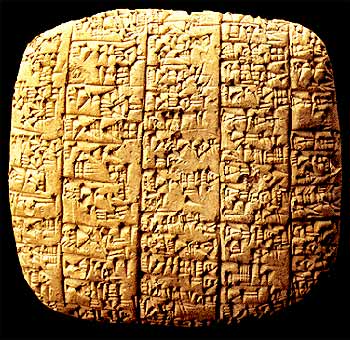

Ancient Egypt — the World’s First Civilization?

Ancient Egypt vies with Mesopotamia, ancient China and the Indus Valley for the title of world’s first civilization. Although some stuff in Mesopotamia is older than the stuff has come to us from Egypt, Egyptian art, architecture and artifacts tend to be more spectacular than Mesopotamian art, architecture and artifacts and there is more of them. “Concerning Egypt," the Greek historian Herodotus wrote in the 5th century B.C., "I will now speak at length, because nowhere are there so many marvelous things, nor in the whole world beside are there to be seen so many worlds of unspeakable greatness."

Anthropologists say there are three definite first Pristine States: Mesopotamia (3300 B.C.); Peru (around the time of Christ), and MesoAmerica (about 100 A.D.). Probable Pristine States include: Egypt (3100 BC), Indus Valley (shortly before 2000 B.C.) and Yellow River Basin in northern China (shortly after 2000 BC).

Egypt, the World’s Longest-Lasting Civilization?

The ancient Egypt civilization lasted for over 2,700 years: from approximately from 2950 B.C. when Egypt was united under Menes, to 300 B.C. when the Persians conquered Egyptian for the second time. Ancient Egypt embraced over 30 dynasties and over 150 rulers. Egyptian civilization existed for well over 3,000 years, if you go from the formation of the first cities at the end of the fourth millennium B.C. to the early years of the Roman empire.

It, China and Mesopotamia are all frequently cited as long-lasting civilizations but which lasted the longest? Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: It turns out, that's not a straightforward question, for a few reasons. First, modern historians and archaeologists don't agree on a single definition of a civilization, including when one begins and when one ends, and many experts are doubtful whether civilizations can be measured in this way. Second, all great civilizations had periods when they were ruled by "foreigners" — the Hyksos in Egypt, for example — which complicates whether they should be considered continuous civilizations. Third, the culture near the beginning of a civilization might have been different from the culture near its end. As a result, many modern historians and archaeologists do not consider the idea of "civilization" useful; instead, they talk of "cultures" and "traditions." [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, May 28, 2023]

By most measures — the use of writing, the establishment of cities (what "civilization" originally meant) or continuous traditions — it seems the Chinese civilization may be the longest-lasting. How it should be measured, however, is disputed. "It depends on how you define civilization and how you define Chinese, because I think there are reasonable multiple ways you can define both of those concepts," Rowan Flad, an archaeologist at Harvard University and expert in the emergence of complex societies in China, told Live Science.

As an example, he highlighted Chinese writing; forms of the same symbols are used today and on the 3,200-year-old Oracle Bones, the earliest examples of writing in China. "When you think about the [Chinese] written language, there's absolutely no controversy that there's continuity from 3,250 years ago or so to the present," he said. But the same criterion can't be used elsewhere, Flad said. For example, the earliest writing in the Americas is attributed to the Olmecs in about 900 B.C. Writing was also known to the Maya after about 250 B.C. But the Incas, who ruled parts of South America for about 400 years until the Spanish conquest in the 16th century, seem to have had no writing (although they used knotted cords called quipu or khipu to encode information.)

Based on the archaeology of early states in what's now Chinese territory, including Neolithic ruins of the Liangzhu culture in the Yangtze River Delta, it's sometimes claimed that Chinese civilization is over 5,000 years old. But some historians see China's present as too different from its past for it to qualify as one continuous civilization. "I don't think that what is happening today in China is closely related to things that happened, say, before 1949 [China's revolution under Mao Zedong] or 1911 [the Xinhai revolution that ended China's last imperial dynasty]," Julia Schneider, a conceptual historian at University College Cork in Ireland, told Live Science.

Mesopotamian writing Schneider, an expert in China's history, noted that pro-Chinese politicians and historians sometimes claim China's civilization is the world's longest-lasting, as "a point of legitimacy." But "what was Chinese? — that is the problem." The region encompassed a vast area and many different ethnicities at different times, and what happened in the Chinese heartlands could be "culturally very far away" than what happened elsewhere, she said.

Next to China, ancient Egypt and then Mesopotamia are usually considered the longest-lasting civilizations. By one estimate, measuring from the time of the first pharaohs and the use of hieroglyphic writing until its native religion was replaced by Christianity, the ancient Egyptian civilization endured for about 3,500 years. But Egypt was sometimes ruled by foreign dynasties, and both hieroglyphics and the Egyptian religion had different forms at certain times.

In Mesopotamia, Sumerian writing began in about 3200 B.C., and worship of Mesopotamian gods probably lasted until the third century A.D., Philip Jones, associate curator and keeper of collections at the Babylonian section of Philadelphia's Penn Museum, told Live Science. By that count, Mesopotamia might be seen as lasting as long as the Egyptian civilization.

Ancient Egypt Versus Mesopotamia

The civilizations of Egypt and Mesopotamia existed pretty much at the same time. Sumer in Mesopotamia is often credited with being the oldest civilization in the world because it came up with a writing system first. Although the two empires were only about 600 miles apart they developed as empires pretty much on their own. This is partly explained by the fact that there was a big desert between them. [Source: H.W. Janson,, History of Art Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.]

For much of its early history Mesopotamia was occupied by rival kingdoms. Few of them were able to exert much influence beyond the borders of their realm. Sumer were not a unified kingdom.. Rather it was like ancient Greece, a composite of often feuding city-states. Babylon was a kingdom that did not control a very large area and did not rule terribly long. With the exception of the brief and unstable Akkadian empire around 2300 B.C. there was no kingdom that ruled over what would qualify as an empire until the Assyrians arrived on the scene in the 9th century B.C.

Another difference between the two cultures is that, at a given time, Egypt flourished under the leadership of one ruler and was relatively peaceful while Mesopotamia was often divided into several kingdoms and city-states and was racked by wars. This too is partly explained by geography. Mesopotamian kingdoms were spread out between two rivers and its many tributaries, and could be easily attacked from any direction, while ancient Egypt was located primarily within one river valley and was removed from the outside world by deserts. Attacks usually only came from the northeast — and to a lesser extent in the south — which meant defenses could be concentrated there. The fact that Mesopotamia was composed of many different kingdoms and city-states that rose, dominated, declined and battled each other also explains why it was never produced a single unified tradition of culture like Egypt. [Janson, Op. Cit]

See First Writing

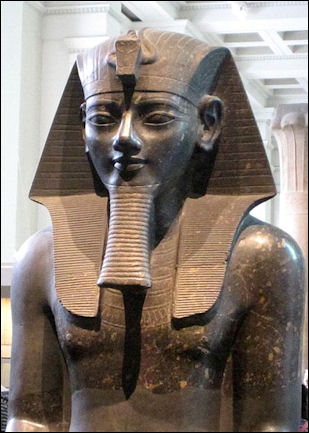

Pharaohs

Amenhotep III Ancient Egypt’s ancient rulers are referred to today as "pharaohs," although in ancient times they each used a series of names as part of a royal titular. The word pharaoh originates from the Egyptian term "per-aa," which means "the Great House." The term was first incorporated into a royal title during the rule of Thutmose III (r. 1479-1425 B.C.). [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

The pharaohs were powerful but distant figures. They were the heads of state and the highest priests and were worshiped as gods. Their power was absolute and they were required to perform certain duties and govern judicially with “ ma’at” (harmony, balance, peace and order). Running the military and deciding policy was only a small part of their job. Succession was from father to son, preferably the son of the king and queen, but if there were no such offspring then the son of one of the Pharaoh’s “secondary” or “harem” wives.

Dorothy Arnold, an Egyptologist at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, told the New Yorker: "The pharaoh was believed in. As whether he was beloved that is beside the point: he was necessary. He was life itself. He represented everything good. Without him there would be nothing." The power of the Pharaohs was based in part on their ability to predict the annual flooding of the Nile.

Pharonic dynasties were closely associated with their numbers. The pharaoh and their wives possessed both throne names and personal names. There were many Nefertitis, almost all queens. Many pharaohs married their sisters and daughters to keep the linage in the family. The longest reign of any ruler was 94 years of the Phiops II, a sixth dynasty pharaoh, who came to power in 2281 B.C. at the age of six.

As a sign of their authority a pharaoh wore a false beard, a lion’s main and a “nemes” or headcloth with a sacred cobra. When offering were made he waived the royal “sekhem” (scepter) over them. The beard on the statue of a pharaoh identifies him as being one with Osiris, god of the dead. The cobra and vulture on his forehead symbolize the Upper and Lower kingdoms of Egypt. The crook and flail held the Pharaoh’s hands symbolized the king's power and also linked him with Osiris (statues of Osiris also have a crook and flail). The pharaoh's power was symbolized by a flabellum (fan) held in one hand.

See Separate Article: PHARAOHS africame.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Egypt and Black Africa

There is a popular view, especially in the African-American community, that the ancient Egyptians “including legendary leaders such as King Tut and Cleopatra — were black Africans. This view is largely dismissed by archaeologists and historians for no other reason than that the the ancient Egyptians painted themselves as whitish or brown while they painted Africans such as Nubians from present-day Sudan as black.

There is a popular view, especially in the African-American community, that the ancient Egyptians “including legendary leaders such as King Tut and Cleopatra — were black Africans. This view is largely dismissed by archaeologists and historians for no other reason than that the the ancient Egyptians painted themselves as whitish or brown while they painted Africans such as Nubians from present-day Sudan as black.

In his arguments that Egyptians were black, Rick Pottfoof of Houston Texas wrote in a letter to National Geographic: “The ancient Egyptians claimed they migrated to Egypt from Ethiopia. What color are the folks in Ethiopia? Herodotus in a roundabout way, stated the Egyptians had dark skin and hair “like wool.” Look at the mask of Tutankhamun. Does he look like someone from Nairobi or Paris or Riyadh? The only reason ancient Egyptians are portrayed as nonblack is that when Egyptology started, white people were enslaving black people and justified it by claiming that blacks were inferior. This wouldn’t hold water if people realized that there had been a black civilization that the ancient Greeks had borrowed many their ideas from.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024