Home | Category: Babylonians and Their Contemporaries / Assyrians / Neo-Babylonians / Life, Families, Women / Art and Architecture

HANGING GARDENS OF BABYLON

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were one of the Seven Wonders of the World. They are said to have been built in 600 B.C. by Nebuchadnezzar for one of his wives who had tired of the barren plains around Babylon and wanted a reminder of her lush mountainous homeland. The gardens were reportedly destroyed by several earthquakes after the 2nd century B.C. Some wondered whether the really existed. They were not even mentioned by Herodotus who visited Babylon when they are said to have existed.

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon may have inspired the story of the Garden of Eden. Scholars still debate what the term “hanging” might have meant, what the gardens might have looked like, how they were watered — and whether they even existed at all. Based on descriptions that were written long after the gardens were said to have existed, the gardens were composed of gardens built on masonry terraces. They were called hanging gardens not because they were really hanging but because they seemed to hang.

The idea behind the Hanging Gardens of Babylon was to create a man-made mountain of lush vegetation. The result was believed to be a square building, 400 feet high, containing five terraces supported by arches that ascended upwards and were planted with grasses, plants, flowers and fruit trees, irrigated by canals and pumps worked by slaves and oxen. There was an avenue of palms. Water came from the Euphrates The queen set up her court inside surrounded by dense vegetation and artificial rain. There was said to be a terrace where she and Nebuchadnezzar sat, admiring their city.

The Hanging Gardens were built on a roughly semi-circular theatre-shaped multi-tiered artificial hill about 25 meters high. At its base was a large pool fed by small streams of water flowing down its sides. Trees and flowers were planted in small artificial fields constructed on top of roofed colonnades. The entire garden was around 120 metres across and it’s estimated that it was irrigated with at least 35,000 litres of water brought by a canal and aqueduct system from up to 80 kilometers miles away. Within the garden itself water was raised mechanically by large water-raising bronze screw-pumps. [Source: David Keys, The Independent, May 6, 2013]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon: An Elusive World Wonder Traced”

by Stephanie Dalley Amazon.com;

“The Hanging Gardens of Babylon” by Jimmy Maher (2021) Amazon.com;

“The City of Babylon: A History, C. 2000 BC - AD 116" by Stephanie Dalley (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World” by Bettany Hughes (2024) Amazon.com;

“How the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World Were Built” Picture Book by Ludmila Henkova (Author), Tomas Svoboda (Illustrator) (2021) Amazon.com;

“Sennacherib, King of Assyria” by Josette Elayi (2018) Amazon.com;

“Sennacherib's "Palace without Rival" at Nineveh” by John Malcolm Russell (1992) Amazon.com;

Seven Wonders of the World

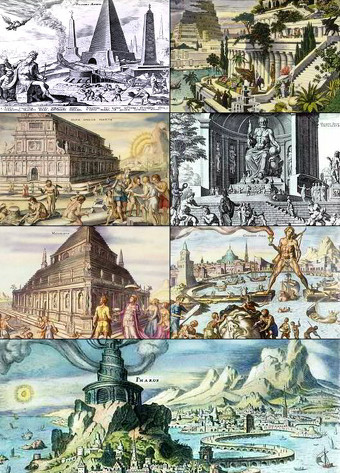

Seven Wonders of World: (left to right, top to bottom): 1) Great Pyramid of Giza, 2) Hanging Gardens of Babylon, 3) Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, 4) Statue of Zeus at Olympia, 5) Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, 6) Colossus of Rhodes, 7) the Lighthouse of Alexandria, depicted by 16th-century Dutch artist Maarten van Heemskerck

The Seven Wonders of the World were first mentioned in the 2nd or 3rd century B.C. They are: 1) the Pyramids of Giza (Egypt); 2) Hanging Gardens of Babylon (Iraq); 3) Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (also known as the Mausoleum of Mausolus) (Turkey); 4) Temple of Diana (Turkey); 5) Colossus of Rhodes (Greece); 6) Statue of Olympia (Greece); 7) The Pharos of Alexandria (Egypt). Some attribute the list to a man called Antipater of Sidon.

The pyramids are the only one of the seven wonders still standing. Part of the Temple of Diana remains. The others vanished after they were toppled by earthquakes and/or scavenged for building material. The images that we have of the seven wonders today are primarily paintings and drawing made by medieval and Renaissance artists over a thousand years after the wonders were gone.

J. L. Montero Fenollós wrote in National Geographic History: Around 225 B.C. a Greek engineer, Philo, produced a list of seven temata — “things to be seen” — that are better known today as the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Many revisions of Philo’s list followed, and other sites were added and removed according to the tastes of the times. But the Philo seven have become canonical, a snapshot of the monuments whose size and engineering prowess awed the classical mind. [Source: J. L. Montero Fenollós, National Geographic History, July 16, 2020]

Only the Pyramids at Giza (built in the mid-third millennium B.C.) remains intact today. Although five of the others have disappeared, or are in ruins, enough documentary and archaeological evidence is available to confirm that they once stood proud, and are not the product of hearsay or legend. Apart from Babylon, all the monuments on Philo’s bucket list lie in or near the eastern Mediterranean, well within the Hellenist sphere of influence. The Hanging Gardens, however, are an eastern outlier, “a long journey to the land of the Persians on the far side of the Euphrates.”

Why seven? Even in ancient times, the number seven was believed to have had mystical significance and bring good. That is also why there were seven seas, seven deadly sins and seven early churches of Christendom. In ancient times, there were different lists of seven wonders and people visited the “wonders” like modern-day tourists.

Descriptions of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon

J. L. Montero Fenollós wrote in National Geographic History: The ingenious Hanging Gardens, Philo writes, were laid out on a large platform of palm beams raised up on stone columns. This trellis of palm beams was covered with a thick layer of soil and planted with all kinds of trees and flowers, a “labor of cultivation suspended above the heads of the spectators.” Aside from its hanging appearance, the gardens’ wondrous nature lay, according to Philo, partly in their variety: “All kinds of flowers, whatever is the most delightful, agreeable and pleasant to the eyes, is there.” Their system of irrigation also inspired wonder: “Water, collected on high in numerous ample containers, reaches the whole garden.” [Source: J. L. Montero Fenollós, National Geographic History, July 16, 2020]

There are a number of Greek references to the Hanging Gardens written several centuries after they are said to have existed. The first-century B.C. geographer Strabo and historian Diodorus Siculus both described the gardens as a “wonder.” Diodorus, a Greek author from Sicily, left one of the most detailed descriptions of the gardens as part of his monumental 40-volume history of the world, Bibliotheca historica. Like Philo, he detailed an elaborate system of supporting “beams”: These consisted of “a layer of reeds laid in great quantities of bitumen. Over this is laid two courses of baked brick, bonded by cement and as a third layer a covering of lead, to the end that the moisture from the soil might not penetrate beneath.” These layers, according to Diodorus, rose in ascending tiers. They were “thickly planted with trees of every kind that, by their great size or other charm, could give pleasure to the beholder,” and were irrigated “by machines raising the water in great abundance from the river.” (Babylon was the jewel of the ancient world.)

In “Geographies”, Strabo (62 B.C. - A.D. 24) wrote: “The hanging garden are called one of the Seven Wonders of the World. The garden is quadrangular in shape, and each side is four plethra in length. It consists of arched vaults, which are situated, one after another, on checkered, cube-like foundations. The checkered foundations, which are hollowed out, are covered so deep with earth that they admit of the largest of trees, having been constructed of baked brick and asphalt — the foundations themselves and the vaults and the arches. The ascent to the uppermost terrace-roofs is made by a stairway; and alongside these stairs there were screws, through which the water was continually conducted up into the garden from the Euphrates by those appointed for this purpose. For the river, a stadium in width, flows through the middle of the city; and the garden is on the bank of the river."

In 50 B.C. Diodorus Siculus, wrote: "The Garden was 100 feet (30 m) long by 100 ft wide and built up in tiers so that it resembled a theatre. Vaults had been constructed under the ascending terraces which carried the entire weight of the planted garden; the uppermost vault, which was seventy-five feet high, was the highest part of the garden, which, at this point, was on the same level as the city walls.The roofs of the vaults which supported the garden were constructed of stone beams some sixteen feet long, and over these were laid first a layer of reeds set in thick tar, then two courses of baked brick bonded by cement, and finally a covering of lead to prevent the moisture in the soil penetrating the roof. On top of this roof enough topsoil was heaped to allow the biggest trees to take root. The earth was levelled off and thickly planted with every kind of tree. And since the galleries projected one beyond the other, where they were sunlit, they contained conduits for the water which was raised by pumps in great abundance from the river, though no one outside could see it being done."

Earliest Accounts of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon

J. L. Montero Fenollós wrote in National Geographic History: After much puzzling over Philo’s, Diodorus’s, and other first-century B.C. accounts of Babylon and its monuments, historians have traced the earliest written sources back to Greek scholars working during and just after the reign of Alexander the Great. Diodorus and Strabo, for example, both drew on accounts of Babylon from fourth-century B.C. writers such as Callisthenes, Alexander’s court historian and great-nephew of the philosopher Aristotle. Scholars believe that the passage in Diodorus’s Bibliotheca historica that describes the Hanging Gardens is derived from a work by a biographer of Alexander the Great, Cleitarchus, who was writing in the late fourth century B.C. His work has not survived but is known through allusions by other authors. The biography was a colorful and gossipy account of Alexander’s age. [Source: J. L. Montero Fenollós, National Geographic History, July 16, 2020]

Another important source of information on the gardens was written by a Babylonian priest named Berossus who lived in the early third century B.C. (soon after the time of Cleitarchus, and several decades before Philo). Judging by other accounts of his lost writings, Berossus seems to have introduced details about the gardens that inspired artists for centuries afterward, writing of high stone terraces lined with trees and flowers. Berossus also wrote that King Nebuchadrezzar II constructed the gardens in Babylon in honor of his wife, Amytis of Media, who longed for the lush mountain landscape of her native Persia. (Under king Cyrus the Great, Persia became the world's first true empire.)

This romantic story has helped fix the gardens in the popular imagination. But historians are faced with a problem: All sources that reference a Babylonian garden remarkable for being suspended or tiered date from the fourth century B.C. at the earliest. The Greek historian Herodotus, writing in the fifth century B.C. — only a century after the time of Nebuchadrezzar — makes no mention of these remarkable gardens when describing Babylon in his Histories. Further dashing hopes that documentary evidence would shed light on the gardens, the texts that have been discovered from the time of Nebuchadrezzar’s reign contain no mention at all of any elevated gardens in the city.

Lack of Evidence for the Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Hanging Gardens of Babylon are held by tradition to be the work of Babylon’s mighty King Nebuchadrezzar II (r. 605-561 B.C.). But there is no direct evidence of this. J. L. Montero Fenollós wrote in National Geographic History: No clue of such gardens has come to light in ruins, or in any reference in Babylonian sources. The hunt for the gardens is one of the most tantalizing quests in Mesopotamian scholarship, and archaeologists are still puzzling out where such gardens may have been located in Babylon, or what was so special about them. [Source: J. L. Montero Fenollós, National Geographic History, July 16, 2020]

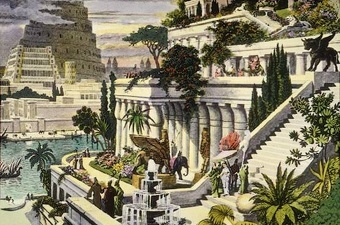

one artist's vision of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon

When Philo wrote his words, Babylon, and the Persians, had been subdued a century before, by Alexander the Great, who had died in Babylon in 323 B.C. Despite the expansion of Greek culture eastward into Central Asia with Alexander’s armies, Babylon and its famed monuments would have struck Philo’s readers as highly exotic and remote.

Faced with this lack of documentary and archaeological evidence, some experts have opted for a radical reframing of the quest for the Hanging Gardens: What if they were not in Babylon at all? This wonder of the world could well be located in another city entirely. This hypothesis is not as radical as it may appear at first: Greco-Roman sources that reference the Hanging Gardens tended to present historical detail interwoven with myth and legend, and their recounting of the history of great Mesopotamian civilizations often confused Assyria and Babylonia. Diodorus, for example, places Nineveh, the capital of the Assyrian Empire, next to the Euphrates, although in fact the city stood on the banks of the Tigris.

In another passage Diodorus describes the walls of Babylon, detailing its rich depiction of animals, hunted by “Queen Semiramis on horseback in the act of hurling a javelin at a leopard, and nearby her husband Ninus, in the act of thrusting his spear into a lion.” No such hunting scene has been found in Babylon. It does, however, correspond closely with neo-Assyrian

Looking for Archaeological Evidence for the Hanging Gardens of Babylon

J. L. Montero Fenollós wrote in National Geographic History: The first-century A.D. Roman Jewish historian Josephus wrote that the gardens lay within Babylon’s main palace. During the first excavations of the ruins of Babylon, directed by the German archaeologist Robert Koldewey between 1899 and 1917, a robust, arched structure was unearthed in the northeast corner of the Southern Palace. [Source: J. L. Montero Fenollós, National Geographic History, July 16, 2020]

Koldewey believed that this was the very structure that had supported the famous gardens. It was made of carved stone, making it more resistant to moisture than mud brick. Its extremely thick walls would have been perfect for supporting the heavy superstructure. In addition, there was evidence of wells, which Koldewey assumed had formed part of the gardens’ irrigation system. Today, however, most scholars agree that the building was probably a warehouse. Several storage jars were excavated from the site, but the strongest evidence is a cuneiform tablet unearthed there that dates to the time of Nebuchadrezzar II. The record contains details about the distribution of sesame oil, grain, dates, spices, and high-ranking captives.

Koldewey’s excavation is most famous for revealing the foundations of a wondrous structure that really did exist: Babylon’s ziggurat, or stepped tower. A decade later, while British archaeologist Leonard Woolley was excavating the ancient Sumerian city of Ur to the southeast of Babylon, he noted regularly spaced holes in the brickwork of the ziggurat there. Might these be evidence of some kind of drainage or irrigation system supplying gardens rising up the face of the Ziggurat of Ur? Perhaps this kind of system, Woolley speculated, was later used to design the Hanging Gardens in Babylon. Spurred, perhaps, by the lively public interest such a theory would awaken, Woolley embraced the theory. But archaeologists largely agree that his sober, initial assessment was correct: The holes were bored to enable the even drying of the brickwork during its construction.

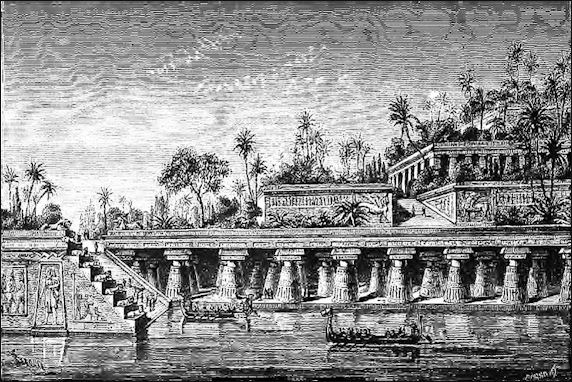

another artist's vision of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Hanging Gardens Were in Nineveh Not Babylon?

In 2013, a leading Oxford-based historian announced that the Hanging Gardens of Babylon were in Babylon –- but were instead located 500 kilometers to the north in the Assyrian city of Nineveh. David Keys wrote in The Independent: “After more than 20 years of research, Dr. Stephanie Dalley, of Oxford University’s Oriental Institute, has finally pieced together enough evidence to prove beyond reasonable doubt that the famed gardens were built in Nineveh by the great Assyrian ruler Sennacherib — and not, as historians have always thought, by King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon. [Source: David Keys, The Independent, May 6, 2013 =]

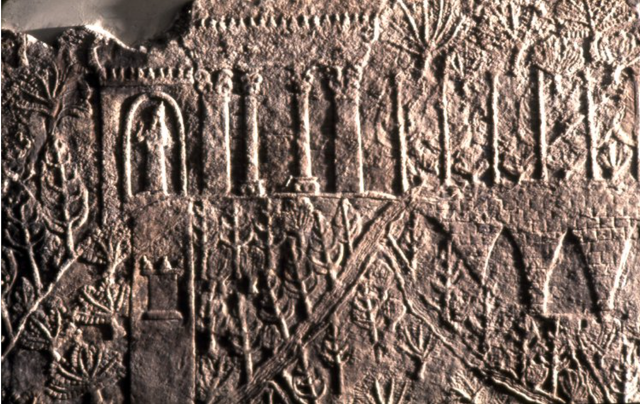

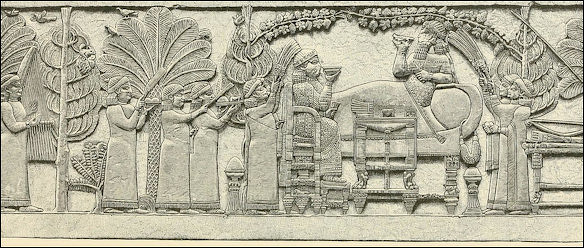

“Detective work by Dr. Dalley –- published in a book by Oxford University Press — yielded four key pieces of evidence. First, after studying later historical descriptions of the Hanging Gardens, she realized that a bas-relief from Sennacherib’s palace in Nineveh actually portrayed trees growing on a roofed colonnade exactly as described in classical accounts of the gardens. Further research by Dr. Dalley then suggested that, after Assyria had sacked and conquered Babylon in 689 B.C., the Assyrian capital Nineveh may well have been regarded as the ‘New Babylon’ – thus creating the later belief that the Hanging Gardens were in fact in Babylon itself. Her research revealed that at least one other town in Mesopotamia - a city called Borsippa – was being described as “another Babylon” as early as the 13 century B.C., thus implying that in antiquity the name could be used to describe places other than the real Babylon. =

“A breakthrough occurred when she noticed from earlier research that after Sennacherib had sacked and conquered Babylon, he had actually renamed all the gates of Nineveh after the names traditionally used for Babylon’s city gates. Babylon had always named its gates after its gods. After the Assyrians sacked Babylon, the Assyrian monarch simply renamed Nineveh’s city gates after those same gods. In terms of nomenclature, it was clear that Nineveh was in effect becoming a ‘New Babylon’. =

“Dr. Dalley then looked at the comparative topography of Babylon and Nineveh and realized that the totally flat countryside around the real Babylon would have made it impossible to deliver sufficient water to maintain the sort of raised gardens described in the classical sources. As her research proceeded it therefore became quite clear that the ‘Hanging Gardens’ as described could not have been built in Babylon.=

“Finally her research began to suggest that the original classical descriptions of the Hanging Gardens had been written by historians who had actually visited the Nineveh area. Researching the post-Assyrian history of Nineveh, she realized that Alexander the Great had actually camped near the city in 331BC – just before he defeated the Persians at the famous battle of Gaugamela. It’s known that Alexander’s army actually camped by the side of one of the great aqueducts that carried water to what Dr. Dalley now believes was the site of the Hanging Gardens. Alexander had on his staff several Greek historians including Callisthenes, Cleitarchos and Onesicritos, whose works have long been lost to posterity – but significantly those particular historians’ works were sometimes used as sources by the very authors who several centuries later described the gardens in works that have survived to this day.” =

Sennacherib, not Nebuchadnezzar, the Builder of the Hanging Gardens?

The bas-relief from Sennacherib’s palace in Nineveh that portray hanging gardens appears to suggest that he — not Nebuchadnezzar — was the builder of the hanging gardens. “It’s taken many years to find the evidence to demonstrate that the gardens and associated system of aqueducts and canals were built by Sennacherib at Nineveh and not by Nebuchadnezzar in Babylon. For the first time it can be shown that the Hanging Garden really did exist” said Dr. Dalley.” [Source: David Keys, The Independent, May 6, 2013 =]

David Keys wrote in The Independent: “The newly revealed builder of the Hanging Gardens,Sennacherib of Assyria - and Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon who was traditionally associated with them - were both aggressive military leaders. Sennacherib’s campaign against Jerusalem was immortalized some 2500 years later in a poem by Lord Byron describing how “the Assyrians came down like a wolf on the fold,” his cohorts “gleaming in purple and gold.” [Source: David Keys, The Independent, May 6, 2013 =]

“Bizarrely it may be that the Hanging Gardens were the first of the seven ‘wonders’ of the world to be so described – for Sennacherib himself referred to his palace gardens, built in around 700BC or shortly after, as “a wonder for all the peoples”. It’s only now however that the new research has finally revealed that his palace gardens were indeed one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Some historians have thought that the Hanging Gardens may even have been purely legendary. The new research finally demonstrates that they really did exist. =

The annals of his reign — inscribed on the Sennacherib prism-shaped stones — the king boasts of the extensive monument-building he undertook: “I raised the height of the surroundings of the palace to be a Wonder for all peoples . . . A high garden imitating the Amanus mountains I laid out next to it with all kinds of aromatic plants.” J. L. Montero Fenollós wrote in National Geographic History: With its reference to wonder and height, the passage echoes many of the key aspects attributed to the Hanging Gardens. Just as classical writers referred to Babylon’s king imitating the landscape of Persia, Sennacherib’s annals detail the gardens’ imitation of Mount Amanus, a range in the extreme south of modern-day Turkey.[Source: J. L. Montero Fenollós, National Geographic History, July 16, 2020]

The "Garden Party" relief depicting Ashurbanipal with his wife

A relief from the time of Sennacherib’s grandson, Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 B.C.), depicts gardens with trees distributed across a slope topped by a pavilion. Water flows from an aqueduct to feed a series of channels filled with fish. The theory that this Ninevan pleasure park could well have been the famed Hanging Gardens is bolstered further by Sennacherib’s reputation for engineering innovation. He declared himself to be of “clever understanding.” The archives of his reign abound with references to ingenious irrigation systems, and some historians credit him with the invention of the Archimedes water screw. Archaeologists have also found an aqueduct system, built during his reign from two million blocks of stone, that brought water to the city across the Jerwan valley. (See "extremely rare" Assyrian reliefs discovered in a canal system near ancient Nineveh.)

The Jerwan structure lies on the route to Alexander the Great’s decisive battle with the Persians, at Gaugamela, in 331 B.C. Dalley argues that it is likely Alexander saw the aqueduct as he passed Nineveh. His inquiries into the sophisticated water systems and gardens of that city seeded the story of the Hanging Gardens, which scholarly confusion then misattributed to Babylon. If the theory is true, it would solve a great archaeological mystery, and leave few in doubt that the Hanging Gardens of Nineveh were a wonder indeed.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024