Home | Category: Assyrians / Life, Families, Women

LIFE IN ANCIENT ASSYRIA

According to Herodotus the Ancient Assyrians who lived in a region east of Egypt, preserved corpses in honey. George P. Monger wrote in “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “Perhaps the ancient Assyrians did have a true system of marriage by purchase, according to the Greek historian Herodotus (484–424 B.C.), with a system of public auction of young women for brides. The women in the auction were considered property of the state, and someone bidding and winning in the auction had to marry the woman he won. In this Assyrian marriage market, the women considered the most beautiful were sold first, and the money raised on their sale went toward a dowry for the less good-looking, as an inducement to buyers. The Thracians, too, had marriage markets where women were sold to the highest bidder. The purchase money went to the parents of the young woman. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

The Assyrians are regarded as the first true hair stylists. Their prowess at cutting, curling, dying and layering hair was admired by other civilizations on the Middle East. Hair and beards were oiled, tinted and perfumed. The long hair of women and the long beards of men were cut in symmetrical geometrical shapes and curling by slaves with curl bars (fire-hearted iron bars).

The Sumerians and Assyrians as well as Egyptians, Cretans, Persians and Greeks all wore wigs. In Assyria, hairstyles often defined status, occupation and income level. During important proceeding high-raking Assyrian women sometimes donned fake beards to show they commanded the same authority as men. Queen Hatshepsut, one of the few female pharaohs of Egypt, did the same thing.

The Kanesh tablets, which date to 1900 B.C. and were found in Turkey, reflect a time in which literacy was becoming widespread among Assyrian traders. According to Archaeology magazine: They used a type of relatively uncomplicated script, known as Old Assyrian cuneiform, characterized by simplified symbols that each represent a syllable or a whole word. Only around 120 distinct characters were used on the tablets found in Kanesh, which likely made it easier for people without formal schooling to learn on their own. “It’s very simple writing,” Assyriologist Cécile Michel of the French National Center for Scientific Research says. “Some of the letters I’m reading, they’re written so poorly, it tells me this person has just learned on the spot and figured out how to write.” [Source: Durrie Bouscaren, Archaeology magazine, November/December 2023]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Everyday Life in Babylon and Assyria” by Georges Contenau (1954) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Near East (Volume II): A New Anthology of Texts and Pictures”

by James B. Pritchard (1976) Amazon.com;

“The Land of Assur and the Yoke of Assur: Studies on Assyria 1971-2005" by J. Nicholas Postgate (2007) Amazon.com;

“Cuneiform Texts from Nimrud: Volume VI - Documents from the Nabu Temple and from Private Houses on the Citadel” by S Herbordt, R Mattila, et al. (2025) Amazon.com;

“Women of Assur and Kanesh: Texts from the Archives of Assyrian Merchants” by Cécile Michel (2020) Amazon.com

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Stephen Bertman (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: Life in the Cradle of Civilization” by Amanda H Podany (2018) Amazon.com;

“Society and the Individual in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Laura Culbertson, Gonzalo Rubio (2024) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian & Persian Costume” by Mary Galway Houston (1920) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat (1998) Amazon.com;

“Assyria: The Rise and Fall of the World's First Empire” by Eckart Frahm (2023) Amazon.com;

“Assyrian Empire: A History from Beginning to End” by History Hourly (2019) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Assyria” by Eckart Frahm (2017) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction” by Karen Radner (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Might That Was Assyria” by H. W. F. Saggs (1984) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Assyria” by James Baikie (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: an Enthralling Overview of Mesopotamian History (2022) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: a Captivating Guide (2019) Amazon.com;

“A History of the Ancient Near East” by Marc Van De Mieroop (2003) Amazon.com;

Assyria 3,900 Years Ago

The Kanesh tablets from Turkey have been dated to 1900 B.C. Durrie Bouscaren wrote in Archaeology magazine: At the time the tablets were written, Assur was a minor independent city-state that had little regional influence — though some 1,000 years later it would lie at the heart of the vast Neo-Assyrian Empire. These early Assyrian traders developed extensive commercial routes spanning from central Anatolia to the Zagros Mountains in modern-day Iran and set up trading stations in cities along the way. Cuneiform tablets that they sent home show that they kept up long-distance marriages with Assyrian women who maintained households in Assur.Some trading posts, such as the one in Kanesh, grew into entire commercial districts within foreign cities, where some Assyrian women came to live full-time [Source: Durrie Bouscaren, Archaeology magazine, November/December 2023]

Kanesh was one of the largest settlements in the ancient world during the nineteenth and eighteenth centuries B.C. Archaeologists believe it had a population of around 30,000 at its height. The city-state was led by a powerful king and queen who texts suggest jointly ruled the realm. Farmers sowed wheat in the autumn and barley in the spring. The Kanesh tablets show that they followed an agrarian calendar, while the Assyrian merchants operated on a system of weeks and months structured around financial matters. Though archaeologists do not know what these Anatolians called themselves, Assyrian traders called them the Nuwau. They had their own culture and worshipped gods and goddesses distinct from those celebrated in Mesopotamian cities. Centuries later, the Indo-European language they spoke would be known as the “language of Kanesh” throughout the Hittite Empire, which dominated Anatolia from about 1600 to 1200 B.C.

The royal couple of Kanesh ruled a strategic area where nearby mines provided copper that could be smelted with tin imported from the east to make bronze. As traders led caravans of donkeys packed with wares between cities, the king and queen of Kanesh collected taxes and tribute that helped fund the construction and maintenance of a massive citadel within the city walls. Excavations of a lower town outside the walls have revealed that Anatolian shopkeepers and families of workers lived there alongside Assyrian traders, whose settlement in Kanesh served as the center of commerce for the entire region. This is where the vast majority of tablets from Kanesh have been uncovered.

Ancient Assyrian Religion

The state religion of Assyria was a copy of that of Babylonia, with one important exception. The supreme god was the deified state. Assur was not a Baal any more than Yahveh was in Israel or Chemosh in Moab. He was, consequently, no father of a family, with a wife and a son; he stood alone in jealous isolation, wifeless and childless. It is true that some learned scribe, steeped in Babylonian learning, now and then tried to find a Babylonian goddess with whom to mate him; but the attempt was merely a piece of theological pedantry which made no impression on the rulers and people of Nineveh. Assur was supreme over all other gods, as his representative, the Assyrian King, was supreme over the other kings of the earth, and he would brook no rival at his side. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Assyrian guardian spirits

The tolerance of Babylonian religion was unknown in Assyria. It was “through trust in Assur” that the Assyrian armies went forth to conquer, and through his help that they gained their victories. The enemies of Assyria were his enemies, and it was to combat and overcome them that the Assyrian monarchs declare that they marched to war. Cyrus tells us that Bel-Merodach was wrathful because the images of other deities had been removed by Nabonidos from their ancient shrines in order to be gathered together in his temple of Ê-Saggil at Babylon, but Assur bade his servants go forth to subdue the gods of other lands, and to compel their worshippers to transfer their allegiance to the god of Assyria. Those who believed not in him were his enemies, to be extirpated or punished. It is true that the leading Babylonian divinities were acknowledged in Assyria by the side of Assur.

But they were subordinate to him, and it is difficult to resist the impression that their recognition was mainly confined to the literary classes. Apart from the worship of Istar and the use of the names of certain gods in time-honored formulæ, it is doubtful whether even a knowledge of the Babylonian deities went much beyond the educated members of the Assyrian community. Nebo and Merodach and Anu were the gods of literature rather than of the popular cult. But even in Babylonia the majority of the gods of the state religion was probably but little remembered by the mass of the people. Doubtless the local divinity was well known to the inhabitants of the place over which he presided and where his temple had stood from immemorial times.

See Separate Articles: MESOPOTAMIAN RELIGION africame.factsanddetails.com

Assyrian Women 3900 Years Ago

Durrie Bouscaren wrote in Archaeology magazine: Although Assyrian legal codes from the time make clear that women were bound to their male relatives and didn’t enjoy the same freedoms as men, the Kanesh archives from 3,900 years ago provide evidence that they were not always truly subservient. The tablets women wrote indicate that they served crucial roles in trading networks, managed finances and workers, and pushed against societal expectations to better their lives. “It’s their own thoughts and writing. It’s not our interpretation of them,” says Yale University Assyriologist Agnete Wisti Lassen. “There’s a deep value to that, to having their own voices heard.” [Source: Durrie Bouscaren, Archaeology magazine, November/December 2023]

Assyriologist Cécile Michel of the French National Center for Scientific Research believes that the letters from the merchants’ wives who stayed in Assur establish that they formed a unique generation of Assyrian women who stepped in to lead their households in an otherwise male-dominated society. “Their lives are organized around the fact that they’re mostly alone in Assur,” she says. “Once women are alone, they’re more documented because they participate in economic life and society.”

Some letters written by Assyrian women describe heartbreak. In one message, a woman named Ummi-Ishara wrote to her sister Shalimma, who had left her husband and children to visit their mother in Kanesh — and refused to return, abandoning her family in Assur. Ummi-Ishara wrote that she feared she would be turned out of her brother-in-law’s home if Shalimma remained in Kanesh. Shalimma’s husband had grown despondent after sending her several letters that went unanswered, Ummi-Ishara warned. “For five days he did not go out of his home,” her sister pressed. “Write me if you are looking for another husband, so I know it. If not, then get ready and leave for here.”

A tablet found in the archive of the merchant Puzur-Assur is a copy of a letter he sent to a woman named Waqqurtum, in which he offered advice on how to improve sales of her textiles in the markets of Kanesh. Many of the texts addressed to or written by women deal in some way with the production of textiles, one of the most lucrative goods Assyrians traded with Anatolians. Together with the enslaved people who lived in their households, women in Assur wove large textiles that their male relatives sold in Kanesh.

Assyrian Businesswomen 3900 Years

Durrie Bouscaren wrote in Archaeology magazine Through their letters, it becomes clear that the women of Assur acted as business partners to their husbands, fathers, and brothers, sometimes debating profit margins and strategizing over which types of textiles would perform best in the marketplace. “The thin textile you sent me, make more like it and send them to me,” a trader named Puzur-Assur wrote to a woman named Waqqurtum, with whom he had an unknown relationship. In the letter, a copy of which he kept in his private archive in Kanesh, Puzur-Assur gave Waqqurtum several tips to improve her sales, based on what he was seeing sell well in the markets of Anatolia. “They should strike one side of the textile, and not pluck it. Its warp should be close,” he insisted. If she couldn’t produce thin textiles, he suggested that she buy them from the markets in Assur and send those instead, lowering her profits, but probably boosting her sales. [Source: Durrie Bouscaren, Archaeology magazine, November/December 2023]

It’s likely that Waqqurtum was related in some way to Puzur-Assur. In Michel’s view, many of the tablets record the inside workings of some of the world’s first multinational family businesses. “The father is the head, the sons settle in Anatolia to trade, and the women are part of the organization, producing textiles,” she says. “All these international trade networks rely on family relationships — they have to trust people.”

Each branch of the family network was financially independent. Individual assets were managed separately, even between married couples. Husbands sent proceeds from their wives’ textile sales back to Assur, as well as gold and silver to cover household expenses and the cost of producing more bolts of cloth. Many of the Kanesh tablets document small loans of silver between household members, which were paid back with interest.

A wealthy businesswoman in Assur named Taram-Kubi sent a series of letters to her husband in Kanesh, a merchant named Innaya. She regularly updated him on a lawsuit he faced in Assur over an irregularity in the sale of lapis lazuli, a semiprecious deep-blue stone that was imported from mines in what is now northeastern Afghanistan. “The cases have been deferred,” she wrote. “Do not be impatient; reinforce your witnesses, certify your tablets, and send them to me by the next caravan.”

In their correspondence, Taram-Kubi and her husband quarreled frequently over money. When Innaya complained about his wife’s spending habits and her lavish lifestyle, Taram-Kubi accused him of clearing the household of its grain stores on a recent visit to Assur. After his departure, she wrote, a famine swept the city, leaving her without barley to feed their children. She insisted that her husband send silver to help her buy food — which he appears to have done. In another tablet, she expressed how much she missed him. “When you hear this letter, come, look to Ashur, your god, and your home hearth, and let me see you in person while I am still alive!” she wrote. “The beer bread I made for you has become too old.”

Assyrian Slaves

The condition of the slave in Assyria was much what it was in Babylonia. The laws and customs of Assyria were modelled after those of Babylonia, whence, indeed, most of them had been derived. But there was one cause of difference between the two countries which affected the character of slavery. Assyria was a military power, and the greater part of its slaves, therefore, were captives taken in war. In Babylonia, on the contrary, the majority had been born in the country, and between them and their masters there was thus a bond of union and sympathy which could not exist between the foreign captive and his conqueror. In the northern kingdom slavery must have been harsher. Slaves, moreover, apparently fetched higher prices there, probably on account of their foreign origin. They cost on the average as much as a maneh (£9) each. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

A contract, dated in 645 B.C., states that one maneh and a half was given for a single female slave. One of the contracting parties was a Syrian, and an Aramaic docket is accordingly attached to the deed, while among the witnesses to it we find Ammâ, “the Aramean secretary.” Ammâ means a native of the land of Ammo, where Pethor was situated. About the same time 3 manehs, “according to the standard of Carchemis,” were paid for a family of five slaves, which included two children. Under Esar-haddon a slave was bought for five-sixths of a maneh, or 50 shekels, and in the same year Hoshea, an Israelite, with his two wives and four children, was sold for 3 manehs. With these prices it is instructive to compare the sum of 43 shekels given for a female slave in Babylonia only four years later.

As a specimen of an Assyrian contract for the sale of slaves we may take one which was made in 709 B.C., thirteen years after the fall of Samaria, and which is noticeable on account of the Israelitish names which it contains: “The seal of Dagon-melech,” we read, “the owner of the slaves who are sold. Imannu, the woman U — — , and Melchior, in all three persons, have been approved by Summa-ilâni, the bear-hunter from Kasarin, and he has bought them from Dagon-melech for three manehs of silver, according to the standard of Carchemish. The money has been fully paid; the slaves have been marked and taken. There shall be no reclamation, lawsuit, or complaints. Whoever hereafter shall at any time rise up and bring an action, whether it be Dagon-melech or his brother or his nephew or any one else belonging to him or a person in authority, and shall bring an action and charges against Summa-ilâni, his son, or his grandson, shall pay 10 manehs of silver, or 1 maneh of gold (£140), to the goddess Ishtar of Arbela. The money brings an interest of 10 (i.e., 60) per cent. to its possessors; but if an action or complaint is brought it shall not be touched by the seller. In the presence of Addâ the secretary, Akhiramu the secretary, Pekah the governor of the city, Nadab-Yahu (Nadabiah) the bear-hunter, Bel-kullim-anni, Ben-dikiri, Dhem-Istar, and Tabnî the secretary, who has drawn up the deed of contract.” The date is the 20th of Ab, or August, 709 B.C. The slaves are sold at a maneh each, and bear Syrian names. Addâ, “the man of Hadad,” and Ben-dikiri are also Syrian; on the other hand, Ahiram, Pekah, and Nadabiah are Israelitish. It is interesting to find them appearing as free citizens of Assyria, one of them being even governor of a city. It serves to show why the tribes of Northern Israel so readily mingled with the populations among whom they were transported; the exiles in Assyria were less harshly treated than those in Babylonia, and they had no memories of a temple and its services, no strong religious feeling, to prevent them from being absorbed by the older inhabitants of their new homes.

Children of Assyrian Slaves

In Assyria, as in Babylonia, parents could sell their children, brothers their sisters, though we do not know under what circumstances this was allowed by the law. The sale of a sister by her brother for half a maneh, which has already been referred to, took place at Nineveh in 668 B.C. In the contract the brother is called “the owner of his sister,” and any infringement of the agreement was to be punished by a fine of “10 silver manehs, or 1 maneh of gold,” to the treasury of the temple of Ninip at Calah. About fifteen years later the services of a female slave “as long as she lived” were given in payment of a debt, one of the witnesses to the deed being Yavanni “the Greek.” Ninip of Calah received slaves as well as fines for the violation of contracts relating to the sale of them; about 645 B.C., for instance, we find four men giving one to the service of the god. Among the titles of the god is that of “the lord of workmen;” and it is therefore possible that he was regarded as in a special way the patron of the slave-trader. It seems to have been illegal to sell the mother without the children, at all events as long as they were young.

In the old Sumerian code of laws it was already laid down that if children were born to slaves whom their owner had sold while still reserving the power of repurchasing them, he could nevertheless not buy them back unless he bought the children at the same time at the rate of one and a half shekels each. The contracts show that this law continued in force down to the latest days of Babylonian independence. Thus the Egyptian woman who was sold in the sixth year of Cambyses was put up to auction along with her child. We may gather also that it was not customary to separate the husband and wife. When the Israelite Hoshea, for instance, was put up for sale in 5 Assyria in the reign of Esar-haddon, both his wives as well as his children were bought by the purchaser along with him. It may be noted that the slave was “marked,” or “tattooed,” after purchase, like the Babylonian cattle. This served a double purpose; it indicated his owner and identified him if he tried to run away. In a country where slaves were so numerous the wages of the free workmen were necessarily low.

Banquet of Ashurnasirpal II (669-626 B.C.)

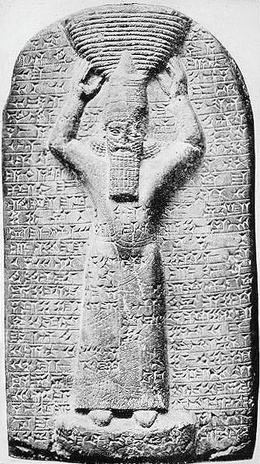

The Banquet Stele of Assurnasirpal II was found in Nimrud and is written in the Akkadian language. It currently resides the Mosul Museum in Iraq, which was savagely destroyed by the Islamic State extremist group. Eva Miller of the University of Oxford wrote: “The Banquet Stele of Assurnasirpal II records the ninth century Neo-Assyrian king's renovation of the city of Kalhu (modern-day Nimrud), which he made his capital. It boasts of the lavish palace and gardens he built, the restoration of temples, and the resettlement and rejuvenation of surrounding towns. The 'banquet' moniker derives from its most unique claim: that in 879 B.C., Assurnasirpal II celebrated his new capital with a lavish feast at which he served 69574 people–male and female, local and foreign envoy–with an obscene amount of meat, poultry, vegetables, and alcohol. This number seems impossibly high, and was likely a typically bombastic royal exaggeration. All the same, this is good evidence that luxurious mass public feasting was one possible feature of royal events.

The Banquet Stele of Ashurnasirpal II reads: I. “This is the palace of Ashurnasirpal, the high priest of Ashur, chosen by Enlil and Ninurta, the favorite of Anu and of Dagan who is destruction personified among all the great gods – the legitimate king, the king of the world, the king of Assyria, son of Tukulti-Ninurta, great king, legitimate king, king of the world, king of Assyria who was the son of Adad-Nirari, likewise great king, legitimate king, king of the world and king of Assyria – the heroic warrior who always acts upon trust-inspiring signs given by his lord Ashur and therefore has no rival among the rulers of the four quarters of the world; the shepherd of all mortals, not afraid of battle but on onrushing flood which brooks no resistance; the king who subdues the unsubmissive and rules over all mankind; the king who always acts upon trust-inspiring signs given by his lords, the great gods, and therefore has personally conquered all the countries; who has acquired dominion over the mountain regions and received their tribute; he takes hostages, triumphs over all the countries from beyond the Tigris to the Lebanon and the Great Sea, he has brought into submission the entire country of Laqe and the region of Suhu as far as the town of Rapiqu; personally he conquered the region from the source of the Subnat River to Urartu. [Source: James B. Pritchard, “The Ancient Near East, Volume II, a book of primary documents from the Near Eas, Edition(s): Wiseman, D.J. 1952,]

“When Ashurnasirpal, king of Assyria, inaugurated the palace in Calah, a palace of joy, and erected with great ingenuity, he invited into it Ashur, the great lord and the gods of his entire country. He prepared a banquet of 1,000 fattened head of cattle, 1,000 calves, 10,000 stable sheep, 15, 000 lambs – for my lady Ishtar alone 200 head of cattle and 1,000 sihhu-sheep – 1,000 spring lambs, 500 stags, 500 gazelles, 1,000 ducks, 500 geese, 5000 kurku-geese, 1,000 mesuku-birds, 1,000 qaribu-birds, 10,000 doves, 10,000 sukanunu-doves, 10,000 other, assorted, small birds, 10,000 assorted fish, 10,000jerboa, 10,000 assorted eggs, 10,000 loaves of bread, 10,000 jars of beer, 10,000 skins with wine, 10,000 pointed bottom vessels with su’u-seeds in sesame oil, 10,000 small pots with sarhu-condiment, 1,000 wooden crates with vegetables, 300containers with oil, 300 containers with salted seeds, 300 containers with mixed raqqute-plants, 100 with kudimmu-spice, 100 containers with […] 100 containers with parched barley, 100 containers with green abahsinnu-stalks, 100 containers with fine mixed beer, 100 pomegranates, 100 bunches of grapes, 100 mixed zamru-fruits, 100 pistachio cones, 100 with the fruits of the susi-tree, 100 with garlic, 100 with onions, 100 with kuniphu seeds, 100 with the […] of turnips, 100 with hinhinnu-spice, 100 with budu-spice, 100 with honey, 100 with rendered butter, 100 with roasted […] barley, 100 with roasted su’u-seeds, 100 with karkartu-plants, 100 with fruits of the ti’atu-tree, 100 with kasu-plants, 100 with milk, 100 with cheese, 100 jars with 'mixture’, 100 with pickled arsuppu-grain, ten homer of shelled luddu-nuts, ten homer of shelled pistachio nuts, ten homer of fruits of the susu-tree, ten homer of fruits of the kabba-ququ-tree, ten homer of dates, ten homer of the fruits of the titip tree, ten homer of cumin, ten honer of sahhunu, ten homer of urianu, ten homer of andahsu-bulbs, then homer of sisanibbe-plants, (iv) ten homer of the fruits of the simburu-tree, ten homer of thyme, ten homer of perfumed oil, ten homer of sweet smelling matters, ten homer of […] ten homer of the fruits of the nasubu-tree, homer of […], ten homer of the fruits of the nasubu-tree, ten homer of zimzimmu-onions, ten homer of olives.

“When I inaugurated the palace at Calah I treated for ten days with food and drink 47,074 persons, men and women, who were bid to come from across my entire country, also 5,000 important persons, delegates from the country Suhu, from Hindana, Hattina, Hatti, Tyre, Sidon, Gurguma, Malida, Hubushka, Gilzana, Kuma and Mushashir, also 16,000 inhabitants of Calah from all ways of life, 1,500 officials of all my palaces, altogether 69,574 invited guests from all the mentioned countries including the people of Calah; I furthermore provided them with the means to clean and anoint themselves. I did them due honors and sent them back, healthy and happy, to their countries.”

Assyrian banquet scene

DNA from Ashurnasirpal-II-Era Tells Show the Presence of Cabbages

In August 2023, scientists announced that they had extracted DNA from 2,900-year-old mud brick from Ashurnasirpal II’s palace and that DNA provided a lot of education about the plants that flourished in the surrounding environment at that time. “There’s such a huge focus on the loss of biodiversity today, but we’ve been lacking sources,” said Sophie Lund Rasmussen, a biologist at the University of Oxford, author a study published in Nature Scientific Reports. The clay brick came from the National Museum of Denmark. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, National Geographic, August 30, 2023]

Tom Metcalfe wrote in National Geographic: The brick was unearthed more than 70 years ago in an archaeological excavation at the site of the Neo-Assyrian capital of Nimrud, near Mosul in what is now Iraq. A remarkable cuneiform inscription on the brick’s surface indicates it formed part of the royal compound: “The property of the palace of Ashurnasirpal, king of Assyria,” the inscription declares. It refers to the second Assyrian king of that name, who built what is known as the Northwest Palace at Nimrud and reigned between 883 and 859 B.C. The fact the inscribed brick can be directly dated to Ashurnasirpal’s rule gave the scientists an approximate date of its manufacture, some three millennia ago.

The researchers took samples from the relatively uncontaminated clay on the new surface of the fracture, then extracted DNA from the samples using a protocol adapted from one designed for porous materials like bone. Subsequent sequencing revealed that the mud brick contained DNA from 34 distinct groups of plants in the ancient clay, including many plants related to cabbages (Brassicaceae) and heathers (Ericaceae). They also found traces of birches (Betulaceae), laurels (Lauraceae) and cultivated grasses from the genus Triticeae—the group that includes barley and wheat.

Arbøll says the predominance of cabbages is curious because there seems to be no record that the Assyrians ate them in the many surviving cuneiform texts that were written around this time, usually on clay tablets. These include several culinary recipes that give their ingredients. “Cabbage doesn’t really figure in the ancient texts,” he says. “It makes you wonder if this was a wild species that hadn’t been cultivated, or if it’s something that hasn’t been recorded or identified in the texts we’ve found.”

Rasmussen adds that the researchers had also seen traces of ancient animal DNA in the samples, and similar techniques could be used to fully identify them. She notes that applying the technique to pottery—which unlike a mud brick is fired in a kiln at temperatures that destroy DNA—may be more difficult. “Perhaps if the pottery hasn’t been burned for long enough, or not burned completely, then there would be DNA left,” she says. “We just don’t know that yet.”

Palaeogeneticist Peter Heintzman, an ancient DNA expert at Stockholm University who wasn’t involved in the study, says he’s concerned any genetic material extracted from the brick could reflect contamination by more modern sources, including air-borne pollen from plants now grown in Iraq and Europe, such as cabbages, wheat, and barley. “The authors do a convincing job of excluding contamination from their lab and reagents,” he says in an email. “However, they do not discuss the possibility that the brick itself may have traces of inherent contamination, especially given its porous nature.”

2,700-Year-Old Luxury Toilet Found in Jerusalem

In October 2021, Israeli archaeologists announced that they had found a rare ancient toilet in Jerusalem that was 2,700 years old, when only the rich had private bathrooms. Associated Press reported: The Israeli Antiquities Authority said the smooth, carved limestone toilet was found in a rectangular cabin that was part of a sprawling mansion overlooking what is now the Old City. It was designed for comfortable sitting, with a deep septic tank dug underneath. “A private toilet cubicle was very rare in antiquity, and only a few were found to date,” said Yaakov Billig, the director of the excavation. “Only the rich could afford toilets.” [Source: Associated Press, October 5, 2021]

The toilet had a seat and a hole in the middle, "so whoever is sitting there would be very comfortable," Billig said. The toilet, which was situated above a septic tank, was found inside a rectangular cabin that would have served as the ancient bathroom. The bathroom also held 30 to 40 bowls, Billig told Haaretz. He speculated that the bowls may have been used to hold air freshener, in the form of a pleasant-smelling oil or incense. [Source: Yasemin Saplakoglu, Live Science, October 8, 2021]

Live Science reported: Within the settlement, the archaeologists also discovered ornamented stones that were carved for various purposes such as for stone capitals — small detailed pieces of stone that form the tops of columns — or window frames and railings, Billig said in the video. Nearby the toilet, Billig and his team discovered evidence of a garden filled with ornamental trees, fruit trees and aquatic plants.All of these relics help the researchers recreate the picture of an "extensive and lush" mansion, according to the statement. Archaeologists first discovered the remains of the ancient mansion on the Armon Hanatziv promenade in Jerusalem two years ago, and excavations are continuing. It was "probably a palace of one of the kings of the Judean Kingdom," Billig said in the video. The world's oldest toilet was discovered in the ruins of Tell Asmar (Eshuan'na) in Iraq. It was dated to around 4,000 years ago.

At the time of the toilet Jerusalem was a busy political and religious center in the Assyrian empire and home to between 8,000 and 25,000 people. “While they did have toilets with cesspits across the region by the Iron Age, they were relatively rare and often only made for the elite,” the 2023 study mentioned below said. “Towns were not planned and built with a sewerage network, flushing toilets had yet to be invented and the population had no understanding of existence of microorganisms and how they can be spread.”

Feces from 2,500-Year-Old Toilets in Jerusalem Indicate People Had Dysentery

Users of 2,500-year-old toilets in Jerusalem were not very healthy according to an analysis of feces found in the toilets. CNN reported: Researchers found traces of dysentery-causing parasites in material excavated from the cesspits below the two stone toilets that would have belonged to elite households in the city. It’s the earliest known evidence of a disease called Giardia duodenalis, although the infection, which causes diarrhea, abdominal cramps and weight loss, had previously been identified in Roman-era Turkey and in medieval Israel. [Source: CNN, May 26, 2023]

“Dysentery is spread by faeces contaminating drinking water or food, and we suspected it could have been a big problem in early cities of the ancient Near East due to over-crowding, heat and flies, and limited water available in the summer,” said Dr. Piers Mitchell, lead author of the study that published in the scientific journal Parasitology and an honorary fellow at the University of Cambridge’s Department of Archaeology, in a statement. Most of those who die from dysentery caused by Giardia are children, and chronic infection in kids can lead to stunted growth, impaired cognitive function and failure to thrive.

The ancient Middle East was where some of the first cities were formed. People often lived together, sometimes with domesticate animals present. Cities such as Jerusalem likely would have been hot spots for disease outbreaks, and illnesses would have spread easily by traders and during military expeditions, according to the study.

Ancient poop is a rich source of information for archaeologists and has revealed an Iron Age appetite for blue cheese, a mystery population on the Faroe Islands and the discovery that the builders of Stonehenge feasted on the internal organs of cattle. Archaeologists excavating the latrines took samples from sediment in the cesspit beneath each toilet seat. They found one seat south of Jerusalem in the neighborhood of Armon ha-Natziv at a mansion excavated in 2019. It likely dates from the days of King Manasseh, who ruled for 50 years in the mid-seventh century B.C. Made of limestone, the toilet has a large central hole for defecating and an adjacent hole likely for male urination. The other toilet seat studied, similar in design, was excavated in the Old City of Jerusalem at a seven-room building known as the House of Ahiel, which would have been home to an upper-class family at the time.

The eggs of four types of intestinal parasites — tapeworm, pinworm, roundworm and whipworm — previously had been identified in the cesspit sediment. But the microorganisms that cause dysentery are fragile and extremely hard to detect, according to the new study. To overcome this problem, the team used a biomolecular technique called ELISA in which antibodies bind onto proteins uniquely produced by particular species of single-celled organisms. The researchers tested for Entamoeba, Giardia and Cryptosporidium: three parasitic microorganisms that are among the most common causes of diarrhea in humans — and behind outbreaks of dysentery. Tests for Entamoeba and Cryptosporidium were negative, but those for Giardia were repeatedly positive.

Nineveh Medical Encyclopaedia

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Archaeologists also found an assemblage of 50 tablets that researchers have only recently realized compose a medical reference manual. Known as the Nineveh Medical Encyclopaedia, it is the oldest systematically organized medical handbook in the world. The compendium contains information about common bodily ailments, listed from head to toe, and provides diagnostic descriptions of each affliction and instructions on how to cure it. This sometimes involves mixing different plants together to create a potion or a salve. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, Features July/August 2024]

For example, one method of curing a headache instructs: Crush and sieve together kukru[an aromatic], burashu [juniper], nikiptu [spurge], kammantu [plant seed], sea algae, and ballukku [an aromatic]. You boil down the mixture in beer, you shave his head, and you put it on as a bandage; then he will recover.

Other ailments require supernatural remedies conjured by reciting magical incantations and appealing to Assyrian gods for help, such as this cure for an eye injury: If a man constantly sees a flash of light, he should say three times as follows: “I belong to Enlil and Ninlil, I belong to Ishtar and Nanaya.” He says this, then he should recover.

Academics in Ancient Assyria

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: In some respects, the life of a Mesopotamian scholar in the seventh century B.C. was not so very different from that of a modern academic. While the former might be responsible for reporting on celestial phenomena and whether they augur well for the king’s reign, and the latter might be searching for evidence of a new subatomic particle to better understand the origins of the universe, in either case, one’s reputation among colleagues is paramount. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2020]

“Let’s take, for example, the lot of an unnamed astrologer who was subjected to a vicious onslaught of peer review from some of the Neo-Assyrian Empire’s top minds after claiming to have sighted Venus around 669 B.C. In a letter to the king Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 B.C.), a fellow stargazer named Nabû-ahhe-eriba, who was part of the inner circle of royal scholars, inveighed, “(He who) wrote to the king, my lord, ‘The planet Venus is visible, it is visible (in the month Ad)ar,’ is a vile man, an ignoramus, a cheat!” Slightly more charitable, though still cutting, was a scholar named Balasî, who tutored the crown prince Ashurbanipal (r. 668–627 B.C.). “(T)he man who wrote (thus) to the king, (my lord), is in ignorance,” Balasî informed Esarhaddon. “The ig(noramus) — who is he?…I repeat: He does not understand (the difference) between Mercury and Venus.”

“These quotations are excerpts from just two of around 1,000 letters and reports written by scholars to Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal in cuneiform on clay tablets that were discovered during nineteenth-century excavations of the archives of the Assyrian capital, Nineveh, near Mosul in Iraq, including Ashurbanipal’s library. While researchers once viewed the ancient scholars as passive instruments of the king who lacked any independence, Assyriologists including Jennifer Singletary, until recently a researcher at the University of Gottingen, are now exploring how the letters illustrate both adversarial and friendly interactions among the scholars, as well as how scholars took distinctive approaches in their writing. “Assyriologists have tended to overemphasize the influence of the king and underemphasize the individuality of the scholars,” says Singletary. “I have been focusing more on the scholars’ relationships with one another and on how their interactions as colleagues and rivals influenced the writing they produced.”

“When they weren’t excoriating fellow scholars they considered incompetent or deceitful, many ancient scholars collaborated with each other, frequently across city lines. This was particularly important when it came to astronomical observations, whose success could depend on the local weather. “Now there are clouds everywhere; we do not know whether the eclipse took place or not,” Bel-ušezib, a Babylonian scholar based in Nineveh, told Esarhaddon. “Let the lord of kings write to Assur and all the cities, to Babylon, to Nippur, to Uruk and Borsippa; maybe they observed it in these cities.”

Having connections to an extensive network of colleagues, particularly if they were widely geographically dispersed, could help a scholar find favor with the king. For instance, when a Babylonian astrologer named Marduk-šapik-zeri, who had fallen out of favor with Esarhaddon, tried to return to the king’s good graces, he cited not just his skill at observing good and bad portents in the sky, but also his connection to “twenty competent scholars worthy of royal desire.” These included a haruspex, or diviner, from Elam, in Iran, several exorcists from Assyria, and various other physicians and chanters.

“Singletary points out that both Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal had good reason to encourage communication among scholars throughout the empire. Both kings were younger sons who were elevated to the throne over older brothers, causing intense controversy and strife during their respective reigns. Keeping tabs on omens discovered by a broad range of scholars was, therefore, highly advantageous. In Ashurbanipal’s case, he became king of Assyria while his older brother was named king of Babylon, a lesser yet competing position. “Ashurbanipal collected scholars almost the same way he collected tablets for his library,” says Singletary. “I wonder if his interest in making sure he was engaging with scholars in Babylonia as well as Assyria had to do with getting insider knowledge from his brother’s portion of the kingdom to make sure there weren’t any uprisings there.”

Assyrian Irrigation Canals

In July 2022, archaeologists announced they had found stunning ancient rock carvings that portray an Assyrian king paying homage to his gods amid a procession of mythical animals along a canal in the Kurdistan region in the north of Iraq. The Assyrian carvings, which are almost 3,000 years old, were uncovered in late 2021 by Italian and Iraqi archaeologists in the Faida district, south of the city of Duhok, about 300 miles (480 kilometers) north of Baghdad, according to the University of Udine in Italy. "There is no other Assyrian rock art complex that can be compared with Faida," said archaeologist Daniele Morandi Bonacossi of the University of Udine. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, July 15, 2022]

Tom Metcalfe of Live Science wrote: The carved panels, dating from about 2800 years ago, were found cut into bedrock above an ancient irrigation canal in the Faida district of Iraq's Kurdistan region. Morandi Bonacossi said that the Faida canal appears to have been built by Assyrian king Sargon for local irrigation, but it became part of a much larger canal network established by Sennacherib. Sargon, who ruled from 722 B.C. until 705 B.C., is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, where he is said to have defeated the Kingdom of Israel in an invasion. He was the father of his successor Sennacherib, who ruled until 681 B.C. and rebuilt the ancient city of Nineveh alongside the Tigris River, on the outskirts of modern Mosul. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, July 15, 2022]

Sennacherib's canals transformed the core regions of the Assyrian Empire from relatively dry farms into highly productive irrigation agricultural areas. "These irrigation networks with their associated monuments were part of highly structured, centrally planned and elite-sponsored programs that engineered the landscape of the Assyrian core," he said. Vandalism, looting and urban expansion — including the construction of a modern aqueduct nearby — now threaten the Faida archaeological site; it is now the subject of a salvage project to document the carvings, protect them and create an archaeological park nearby.

See Separate Article: IRRIGATION IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024