Home | Category: Assyrians / Art and Architecture

ASSYRIAN ART

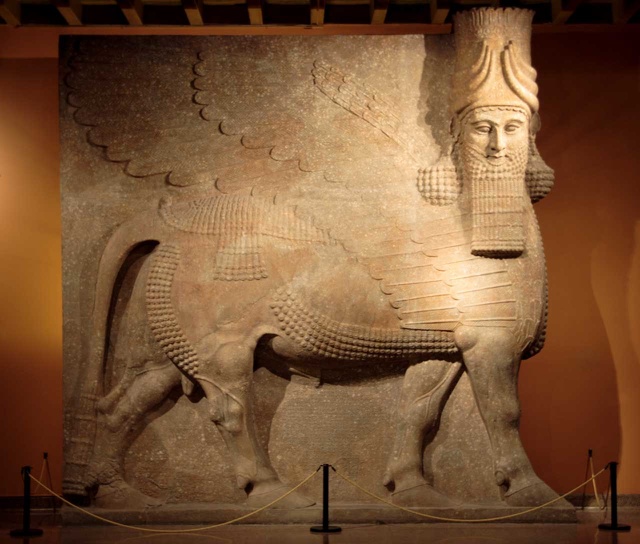

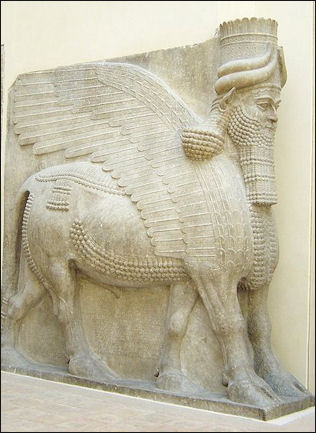

Assyrian Gate The Assyrians produced colossal human-headed winged bulls. The most famous of theses were carved from alabaster and stood outside a palace gateway of the Palace of Sargon II at Dur Sharrukin. There were two of them. They each stood 16 feet high and weighed 40 tons. Assyrian a human-headed, winged bulls were called “ lamassu” . They were often accompanied by four-winged deities called a “apkallu”.

New York Times art critic Holland Carter wrote: “Assyrian art is about winning through intimidation. The carved narrative reliefs...obsessively dwell on hair-raising battles and sadistic wildlife hunts. The half human raptor...was intended to advertise the aggressive otherworldly resources the king could command.”

Assyrian masterpieces at the British Museum include several wall reliefs depicting lion hunts and other activities of the day; bronzes like the “Bronze Head of Pazuzu” and clay cuneiform-inscribed talents that once adorned the palaces of rulers like Ashurnasirpal II (833-859 B.C. ) of Nimrud.

The Assyrians spread their art and culture throughout their empire. Art for Persia in particular has strong Assyrian influences. A 9th century Assyrian relief is the first known depiction of people shaking hands.

The Assyrians laid the foundations for the Persian, Greek, Roman and Parthian empires.

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Assyrian Palace Sculptures” by Paul Collins (2008) Amazon.com;

“Assyrian Sculpture” by Julian E. Reade (1998) Amazon.com;

“Art and Empire: Treasures from Assyria in the British Museum” by John E. Curtis, Julian E. Reade Amazon.com;

“The Mythology of Kingship in Neo-Assyrian Art” by Mehmet-Ali Ataç (2010) Amazon.com;

“A Manual of Ancient Sculpture, Egyptian – Assyrian – Greek – Roman: With One Hundred and Sixty Illustrations” by George Redford (2021) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: Ancient Art and Architecture” by Zainab Bahrani (2017) Amazon.com;

“Nimrud: The Queens' Tombs” by Muzahim Mahmoud Hussein, McGuire Gibson (2016) Amazon.com;

“An Examination of Late Assyrian Metalwork: with Special Reference to Nimrud”

by John Curtis (2013) Amazon.com

“The Published Ivories from Fort Shalmaneser, Nimrud” by Georgina Herrmann , H. Coffey, et al. (2004) Amazon.com;

“Assyria: The Rise and Fall of the World's First Empire” by Eckart Frahm (2023) Amazon.com;

“Assyrian Empire: A History from Beginning to End” by History Hourly (2019) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Assyria” by Eckart Frahm (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Art and Architecture of Mesopotamia” by Giovanni Curatola, Jean-Daniel Forest, Nathalie Gallois (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient (The Yale University Press Pelican History of Art) by Henri Frankfort , Michael Roaf, et al. (1996) Amazon.com;

“Art of the Ancient Near East: A Resource for Educators” by Kim Benzel, Sarah Graff, Yelena Rakic Amazon.com;

“Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus”

by Joan Aruz and Ronald Wallenfels (2003) Amazon.com;

Assyrian Art Masterpieces

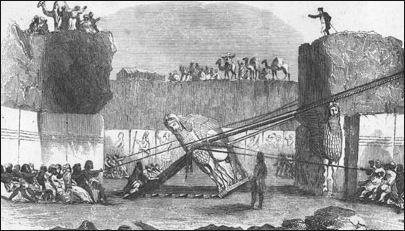

Apkallu from Nimrud Among the masterpieces of Assyrian art are 10-foot-high limestone panels with human-faced creatures with lion and bull bodies from the audience hall of the palace of Ashuraspal II at Nimrud; a 14.5-foot-high gypsum winged bull relief, with a human head, circa 710 B.C., taken from the Citadel gate at Duk Sharrukin near Nivenah; and an alabaster relief of a winged god taken from outside a palace door at the same site. A huge human-headed bull at the site was hacked into pieces by looters.

A gypsum piece from the 8th century B.C. depicts two muscular warriors with Semitic features, curled beards and pointed helmets. A frieze from Nivenuh of the last great Assyrian ruler Ashurbanipal, shows him killing a lion with a spear while another lion tried to leap on a horse. An 8th century B.C. ivory plaquette of a winged griffin unearthed from Nimrud was a decorative pannel for furniture.

Treasures from the Assyrian period at the Iraq National Museum include an entire room devoted to ivories and gold ornaments from the 8th century Assyrian capital of Nimrud. Other objects from Nimrud include a cuneiform calendar dated at 850 B.C., consisting of daily instructions for the 7th month of the year; the Lioness killing a Nubian shepherd, an 8th century B.C. relief made of ivory and decorated with inlays of gold, carnelian and lapis lazuli.

Assyrian Bas-Reliefs

The Assyrians developed relief sculpture to a high art. Influenced by Babylonian art, Assyrian art includes sculptures and friezes of bloody battles, hunting scenes, human-headed bulls, fighting bulls and lions, winged bulls, processions of kings and deities, and a king spearing a lion. Human figures are flat two-dimensional like Egyptian figures but have more developed bodies and muscles and have elaborately-braided beards and hairstyles. Animals are life-like and filled with rippling muscles, motion and ferocity.

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: In one room in Ninenveh, archaeologists discovered a series of reused carved panels that represent some of the finest Assyrian artwork found in the city for a century. The panels date to the reign of Sennacherib and were likely commissioned to be displayed in what the king called his “Palace Without Rival.” Sennacherib, like other Assyrian rulers, documented his accomplishments, in both textual and figurative form, and the newly uncovered reliefs seem to depict the ruler’s military campaign in 701 B.C. against the Kingdom of Judah, an event recorded in the Bible. They attest to a time when the Neo-Assyrians were one of the richest, fiercest, and most powerful people in the world, and are reminders of an era when Nineveh was the jewel of their empire. The reliefs are just one example of the extraordinary finds that have surfaced during renewed archaeological work at the site and in its environs. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, Features July/August 2024]

In one Assyrian bas-relief, a king stands before are two royal prisoners, Tirhaka, the King of Ethiopia, and Ba’alu the King of Tyre. To emphasise his greatness in contrast to the insignificance of his enemies, the king portrays himself as of commanding stature. At the head of the stone, the emblems of the great gods of Assyria, Ashur, Sin, Shamash, Ishtar, Marduk, Nebo, Ea, Ninib, and Sibitti (seven circles), with Ashur, Ishtar of Nineveh, Enlil, and Adad standing on animals. Diorite stele found at Sendschirli in Northwestern Syria. This work is now in the Royal Museum of Berlin.

Reliefs from the palace of Ashuranasirpal II at Nimrud

Blessing genie of Dur Sharrukin Describing the reliefs from the palace of Ashuranasirpal II at Nimrud, Holland Carter, the art critic for the New York wrote: “Like most official art, these images adhere to a formula, but seen in isolation their stylized virtuosity stands out. The fringe of the birdman’s robe and the bulging calf of his leg are delicately executed. His ramrod pose has a courtly grace. In one hand he carries a purse-size bucket of holy water; in the other he dabs the air with a fruit that looks like a pine cone, as if removing a pesky stain from the wall.”

Reliefs of Ashuranasirpal II himself depict the king as warrior, priest and protector of Assyria. Each scene has a cuneiform text in Akkadian listing his many victories and accomplishments. Often he is accompanied by protective deities — bird heads, supernatural guardians and winged human figures — and stylized representations of the tree of life. At one time dozens of these large figures in stone reliefs lined the king’s throne room. Originally painted in bright colors, they were meant to intimidate visitors.

Describing a relief of Ashuranasirpal II from Nimrud displayed at Bowdoin College Museum Wendy Moonan wrote in the New York Times: “Beautifully carved in gypsum and nearly six feet tall, it depicts in profile a regal figure walking to the viewers right. He can be identified as a king because he wears a tall conical hat, a symbol of power and prestige. He wears a long embroidered cape, an elaborate earrings, a necklace and a bracelet with a large rosette, and carries a dagger and whetstone, He raises his right arm in a gesture of acknowledgment or greeting. His left hand holds a bow, the symbol of his patroness, the goddess of war and love. “

“But something is very wrong here, The king has been disfigured. His bow is broken in the middle. His right wrist and his Achilles tendons have been brutally slashed. His nose and ears are damaged, and one eye has been chipped out, The bottom of his beard has been hacked away.” It is believed the reliefs were defaced by the Medes after they captured Nimrud in 612 B.C. , more than 250 years after the reliefs were made. Some scholar believe it was a “magical attack as well as a symbolic disfigurement.”

Art in the North Palace of Nineveh

According to National Geographic: Many of the reliefs in the throne room of the North Palace of Nineveh built under Ashurbanipal depict battle scenes, commemorating Ashurbanipal’s great military victories, including the campaigns against Babylon, Elam, Egypt, and the Arab tribes. Although Ashurbanipal rarely accompanied his soldiers onto the battlefield, he created a powerful iconography through these elaborate reliefs that would preserve a legacy as a great military leader. [Source: National Geographic, National Geographic,, August 25, 2022]

Assyrian royal lion hunt In the palace’s private rooms, which few had access to, the king chose a slightly different emphasis for the reliefs. In these spaces the military-themed reliefs are mixed with scenes that depict the king celebrating his triumphs. One panel shows Ashurbanipal performing a ritual libation using the severed head of the Elamite king Teumman, whom he defeated at the Battle of Til-Tuba (the defeated king’s head was also paraded through the streets of Nineveh). These images of military victories and triumphal celebrations seem contrived to send visitors a clear message of the price paid by those who dared to resist Assyrian power.

Perhaps the most famous pieces of art from the North Palace are the reliefs of a lion hunt, the sport of kings in ancient Assyria. Rendered in a striking, lifelike manner, Ashurbanipal and his retinue kill multiple lions, whose painful deaths are shown in gruesome detail. This stone relief depicts with astonishing realism the death throes of a male lion that has been mortally wounded by Ashurbanipal during a ritual lion hunt. It belongs to a series of stone panels showing hunting scenes that decorated the hallways in Ashurbanipal’s North Palace in Nineveh. Such hunts were sacred to Assyrian kings as they symbolized the king’s ability to protect his people. As early as the ninth century B.C., a royal inscription records Ashurnasirpal II boasting of his hunting prowess: “The gods Ninurta and [Nergal, who love my priesthood, gave to me the wild beasts and commanded me to hunt]. 300 lions ... six strong [wild] virile [bulls] with horns ... and the winged birds of the sky.”

In the Sebetti Panel from the north palace in Nineveh, circa 645-640 B.C., Three bearded figures on a relief once stood watch over an entrance to the throne room of Ashurbanipal’s North Palace. Painted in colorful hues, they were more than just mere decoration. Researchers have identified them as representations of the Sebetti, a group of minor warrior deities from the Mesopotamian pantheon. Each wields an ax in the right hand and a dagger in the left (analysis of the relief shows that they originally were armed with bows rather than these handheld weapons). These three protective spirits were probably complemented by another relief (which has not been recovered) featuring four more figures, as the Sebetti were depicted in groups of seven and associated with the Pleiades, a closely grouped cluster of seven stars in the constellation Taurus. Another common depiction of the Sebetti was an emblem of seven dots. Worship of these spirits dated back centuries before Ashurbanipal’s rule, as evidenced in inscriptions and temples built by earlier kings Sennacherib (reigned 705–681 B.C.) and Ashurnasirpal II (reigned 883-859 B.C.).

Treasure of Nimrud

In the 1989 and 1990, four tombs, dated to the 8th and 9th century, believed to belong to queens (or at least consorts) of Ashurnasipal II were excavated in a royal palace in Nimrud. One tomb alone contained over 28 kilograms of gold. The items are the among the most impressive examples of Assyrian art — or for that matter ancient gold — ever found.

In the 1989 and 1990, four tombs, dated to the 8th and 9th century, believed to belong to queens (or at least consorts) of Ashurnasipal II were excavated in a royal palace in Nimrud. One tomb alone contained over 28 kilograms of gold. The items are the among the most impressive examples of Assyrian art — or for that matter ancient gold — ever found.

Archaeologists found 40 kilograms of treasures and 157 objects, including a golden mesh diadem with tiger eye agate, lapis lazuli; a gold child’s crown embellished with rosettes, grapes, vines and winged female deities; 14 armlets and arm band with cloisonne and turquoise; enameled and engraved gold jewelry; four anklets including, one gold anklet weighing a kilogram; 15 vessels, including one with scenes of hunting and warfare; 79 earnings; 30 rings; many chains; a palm crested plaque; gold bowls and flasks; a bracelet inlaid with semiprecious stones and held together with a pin; and rare electrum mirrors.

The jewelry was worn by royal consorts of Assyria’s rulers, A finely worked gold necklace features clasp in the shape of entwined animal heads. A finely wrought gold crown is topped by delicate winged females. There also chains of tiny gold pomegranates and earrings with semi-precious stones.

Discovery of Nimrud Treasures

In 1988 Iraqi archaeologist Muzahem Hussein uncovered two 8th century B.C. tombs under the royal palace in Nimrud. He discovered the site when he realized he was standing on some great vaults while putting some bricks back in place After two weeks of clearing away dirt and debris he caught his first glimpse of gold.

The first tomb was still sealed and contained a woman who was 50 or so and a collection of beautiful jewelry and semiprecious stones. A second tomb, about 100 meters away, contained the two women, perhaps queens. They were placed in the same sarcophagus one on top of the other, wrapped in embroidered linen and covered with gold jewelry. One of the women had been dried and smoked at temperatures of 300 to 500 degrees, the first evidence of mummification-like practices in Mesopotamia.

The second tomb contained a curse, threatening the person who opened the grave of Queen Yaba (wife of powerful Tiglthpilese II (744-727 B.C.) with eternal thirst and restlessness, with a specific warning about placing another corpse inside. The curse was written before the second corpse was placed inside. The two women inside were 30 to 35 years of age, with the second being buried 20 to 50 year after the first. The first is thought to be Queen Yaba. The other is thought to be the person identified by a gold bowl found inside the sarcophagus that reads: “Atilia, queen of Sargon, king of Assyria: who rule from 721 ro 705 B.C.”

A third tomb excavated in 1989 had been looted but looters missed an antechamber that contained three bronze coffins: 1) one with six people, a young adult, three children, a baby and a fetus.; 2) another with a young woman, with a gold crown, thought to have been a queen; and 3) a third with a 55- to 60-year-old man, and a golden vessel that appears to have identified him as a powerful general that served under served several kings.

The treasure was on display for just a few months before the 1991 Persian Gulf War, when it was packed away for protection and put in a vault beneath Baghdad’s central bank . Though the bank was bombed, burned and flooded during the 2003 invasion of Iraq the treasure reportedly was undamaged.

from the treasures of Nimrud

2,700-Year-Old Rock Carvings Discovered in Iraq's Mosul

In 2022, archaeologists in northern Iraq announced they had unearthed 2,700-year-old rock carvings featuring war scenes and trees from the Assyrian Empire. Associated Press reported: The carvings on marble slabs were discovered by a team of experts in Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city, who have been working to restore the site of the ancient Mashki Gate, which was bulldozed by Islamic State group militants in 2016. Fadhil Mohammed, head of the restoration works, said the team was surprised by discovering “eight murals with inscriptions, decorative drawings and writings.” [Source: Associated Press, October 26, 2022]

Mashki Gate was one of the largest gates of Nineveh, an ancient Assyrian city of this part of the historic region of Mesopotamia. The discovered carvings show, among other things, a fighter preparing to fire an arrow while others show palm trees. “The writings show that these murals were built or made during the reign of King Sennacherib,” Mohammed added, referring to the Neo-Assyrian Empire King who ruled from 705 to 681 B.C.

The Islamic State group overran large parts of Iraq and Syria in 2014 and carried out a campaign of systematic destruction of invaluable archaeological sites in both countries. The extremists vandalized museums and destroyed major archaeological sites in their fervor to erase history.

Faida Rock Carvings Show Procession of Gods Riding Mythical Animals

In July 2022, archaeologists announced they had found stunning ancient rock carvings that portray an Assyrian king paying homage to his gods amid a procession of mythical animals in the Kurdistan region in the north of Iraq, after being hidden for several years to prevent damage by the Islamic State militant group (ISIS). The Assyrian carvings, which are almost 3,000 years old, were uncovered in late 2021 by Italian and Iraqi archaeologists in the Faida district, south of the city of Duhok, about 300 miles (480 kilometers) north of Baghdad, according to the University of Udine in Italy. It's the first time in almost 200 years that any comparable Assyrian rock carvings have been found, and the discovery is thought to highlight an ancient period of expansion in the Assyrian Empire. With the exception of the carvings at the archaeological site of Khinnis, discovered near the city of Mosul in 1845, "there is no other Assyrian rock art complex that can be compared with Faida," said archaeologist Daniele Morandi Bonacossi of the University of Udine. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, July 15, 2022]

The carved panels, dating from about 2800 years ago, were found cut into bedrock above an ancient irrigation canal in the Faida district of Iraq's Kurdistan region. The unearthed panels show a procession of the seven main Assyrian gods and goddesses, standing or seated on mythical animals, and the Assyrian king Sargon II. So far, the archaeologists have unearthed 10 panels of intricate carvings in bedrock above what was once an ancient canal. Like the famous Assyrian carvings at Khinnis, these are sculpted as reliefs, with the prominent figures raised from a solid background.

Built during the eighth century B.C., the 4-mile-long (6.5 kilometers) canal carried water to farmland in the Faida district, but it was filled in long ago. "It is highly probable that more reliefs and perhaps also monumental celebratory cuneiform inscriptions are still buried under the soil debris that filled the Faida canal," Morandi Bonacossi told Live Science.

See Separate Article: IRRIGATION IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com

Discovery of the Faida Rock Carvings

The Faida carvings were first seen in the 1970s, and surveys of the site began in 2012, Morandi Bonacossi said. But the archaeological work had to be abandoned and hidden when ISIS became active in the region and captured nearby Mosul in 2014. As a result, archaeologists were only able to return and start a full scientific excavation of the site in 2019, after ISIS was driven out of the region, he said. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, July 15, 2022]

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: Uncovering the Faida reliefs was a long time coming. The site is located in Iraqi Kurdistan, which was off-limits to archaeologists for much of the twentieth century because of strife between its people and the government in Baghdad. During a brief visit to Faida in the early 1970s, British archaeologist Julian Reade spotted three sections of rock-cut reliefs poking out of soil that had washed down from nearby mountains, filling the canal. In 2012, Morandi Bonacossi led a survey of the waterway’s four-mile length and identified six more relief sections cropping up from the ground. Only a foot or so at the top of the carvings was visible, revealing the tips of crowns that Morandi Bonacossi thought likely belonged to Assyrian deities. When ISIS advanced into the area, the archaeologists had to abandon their work. By late 2019, however, it was safe for Morandi Bonacossi to return with the Kurdish-Italian Faida Archaeological Project, along with his codirector, Hasan Ahmed Qasim of the Duhok Directorate of Antiquities. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2020]

In the process of excavating the previously known relief sections, the team discovered one more, for a total of 10. Each section measures about six feet high and 15 feet wide. As the archaeologists removed the soil from the carvings, they found that each panel depicted an identical scene in which statues of seven of the most important Assyrian deities are carried on the backs of animals—some real, some fantastical—while an Assyrian king stands at either end of the procession. The Assyrians saw these deities as immense in both physical form and in the power they wielded over humanity. Like humans, they were subject to emotions and capable by turns of compassion and cruelty. They were also amenable to prayers and hymns, but, as depicted in the Faida reliefs, the king shared a much more direct connection to them than did anyone else.

Images in the Faida Rock Carvings

Each panel of the Faida Rock Carving shows a procession of the seven main ancient Assyrian gods and goddesses, who are standing or sitting atop striding dragons, lions, bulls and horses. "The deities can be identified as Ashur, the main Assyrian god, on a dragon and a horned lion; his wife Mullissu sitting on a decorated throne supported by a lion; [and] the moon god Sin on a horned lion," he said. According to Live Science: The procession also shows the Assyrian god of wisdom mounted on a dragon, the sun god Shamash on a horse, the weather god Adad on a horned lion and a bull, and Ishtar, the goddess of love and war, on a lion. All the gods and goddesses are facing in the direction of the water that would have been flowing in the canal beneath them, he said. The Assyrian king Sargon — a namesake of the much earlier Mesopotamian king Sargon the Great — appears twice in each of the carved panels, once at each end, he said. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, July 15, 2022]

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: First in the reliefs’ divine parade is Ashur, the chief Assyrian god. He was originally the local god of his namesake city, an early Assyrian capital, but grew in stature as the empire expanded. Ashur was considered the true ruler of Assyria, and the king his earthly representative. At the behest of the god, Neo-Assyrian kings led annual military campaigns to extend his—and their—territory, with some of their greatest gains occurring under Sennacherib and his father and predecessor, Sargon II (721–705 B.C.). At the empire’s height, the Assyrians controlled lands from western Iran to the Mediterranean and from Anatolia to Egypt. The kings moved huge numbers of people from one end of the empire to the other—in part to neutralize potential rebellions, and in part to populate new cities and provide farm labor in rural areas. Once they belonged to the empire, these new residents were expected to worship Ashur and the rest of the Assyrian pantheon.

In the carvings, Ashur stands far taller than the rest of the deities atop a bull and a mušhuššu, a mythical Mesopotamian dragon that has the body of a snake, the front legs of a lion, and the rear feet of an eagle. Following Ashur is his wife, Mullissu, who sits on a decorated throne borne by a lion. Next in line is Sin, the moon god, supported by a horned lion. Then, propped up on a mušhuššu is a deity Morandi Bonacossi believes to be the god of wisdom, Nabu, who gave people the gift of writing. After Nabu is the sun god, Shamash, who was also the god of justice—no earthly doings escape the notice of the sun. Shamash stands atop a horse; he was associated with horses because the sun disc was thought to be transported across the sky in a horse-drawn chariot. The weather god, Adad, who could bring gentle rains or calamitous storms depending on his mood, is next, brandishing lightning bolts in his right hand and standing on a horned lion and a bull. Bulls were associated with the weather god because the Assyrians believed thunder was the sound of their stampeding hooves. Last among the deities is Ishtar, the goddess of love and war, wearing a star-topped crown and conveyed by a lion.

Morandi Bonacossi has identified the figure standing at each end of the processions as an Assyrian king, based on the cone-shaped tip of his tiara, the mace he holds in his left hand, and a hand-to-nose gesture used by royals to demonstrate respect to the gods. Although scholars have long believed that the Faida canal must have been part of Sennacherib’s regional irrigation network, Morandi Bonacossi argues, in part based on stylistic features of the reliefs, that it was actually built by Sargon II. In the upcoming field season, he hopes to unearth further evidence to bolster his case. “Maybe we will find an inscription naming the king who built the canal and carved the reliefs,” he says.

Winged Figures in Mesopotamian Art

“Kneeling Winged Figures before the Sacred Tree”is on an alabaster slab found in the North-West Palace at Nimroud and made during the reign of Ashumasirpal (883-859 B.C.). , Morris Jastrow wrote: “The sacred tree or the tree of life, as it should perhaps be called, is frequently portrayed on Assyrian seal cylinders in all manner of variations. Though found also on Babylonian specimens its earliest occurrence, indeed, being on a boundary stone as a decoration of the garment of a Babylonian ruler, Marduk-nadinakhe, it is a distinctive characteristic on Assyrian monuments. The tree intended is clearly the palm, though it becomes conventionalised to such a degree as to lose almost all the traits of that species. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“Winged figures preferably carry a cone in one hand and a basket in the other, or a branch in one hand and a basket in the other. On the seal cylinders the variations are even more numerous. Instead of winged figures, we find bulls or lions with birds and scorpions to either side of the tree, or the winged figures stand on sphinxes, or human headed bulls take the place of the winged figures; and more the like. It is evident that the scene is in all cases an adoration of the tree. In a purer form this adoration appears on seal cylinders like No. 687 in Ward, Cylinders of Western Asia (p. 226), where we find two priests clad in fish robes —as attendants of Ea—with a worshipper behind one of the priests; on No. 688 with only one priest and a worshipper to either side; or No. 680, the goddess Ishtar on one side of the tree, and a god—perhaps Adad—on the other side with a worshipper behind the latter; or still simpler on No. 689 where there is only one priest and a worshipper to either side of the tree.

“The winged figures in such various forms represent, as do also the sphinxes, protecting powers of a lower order than the gods, but who like Ishtar and Adad in the specimen just referred to are the guardians of the sacred tree, with which the same ideas were associated by the Babylonians and Assyrians as with the tree of life in the famous chapter of Genesis, or as with trees of life found among many other peoples. The cones which the winged figures beside the tree hold indicate the fruit of the tree, plucked for the benefit of the worshippers by these guardians who alone may do so. A trace of this view appears in the injunction to Adam and Eve (Genesis ii.) to eat of the fruit of all the trees except the one which, being the tree of knowledge, was not for mortal man to pluck—as little as the fruit of the “Tree of Life.”

On a “Winged Figure with Palm Branch and Spotted Deer” at the features a winged figure carrying a branch of the palm tree and an ibex, Other images contain a winged figure with basket and branch and a winged figure with cone and basket like on the representation of the tree of life. Jastrow wrote: “The palm branch symbolises the tree of life which has been plucked for the benefit of the king to whom the branch and therefore the blessings of life are thus offered. The deer as well as the ibex is a sacrificial animal, and symbolises the gift offered by the royal worshippers in return, and received on behalf of the god by the winged figure acting as mediator or priest. Attached to the figure (alabaster slab) is the so-called standard inscription of Ashurnasirpal, King of Assyria (883-859 B.C.) in whose palace (N.-W. Palace of Nimroud) at Calah it was found. Now in the British Museum.”

Statue of Lamassu — Deity with a Human Head and a Winged Bull’s Body

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: A massive sculpture of a lamassu, a deity with a human head and a winged bull’s body, was unearthed at the Neo-Assyrian (ca. 883–609 B.C.) capital of Dur-Sharrukin, in northern Iraq. The statue was partially excavated in the 1990s and later reburied to safeguard it from harm. The head of the lamassu statue was missing, but the figure was otherwise in exceptional condition. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, Features July/August 2024]

The Lamassu once stood as a protective guardian at a gate into the ancient city of Dur-Sharrukin, near modern Khorsabad. There were rows of delicately overlapping feathers, the hanging curls of a man’s beard, and the cloven hooves of a bull, all skillfully carved from shining white alabaster. The sculpture, which stood 12.5 feet tall and weighed nearly 20 tons.

Given the intense events that had occurred around the site, it was a marvel that the sculpture remained in such good condition. “The lamassu had vanished between anti-tank trenches and bunkers,” says Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne University archaeologist Pascal Butterlin. “Considering this situation, with traces of heavy bombing and fights all around, it’s a miracle that it wasn’t further damaged.” Only the statue’s head was missing, but Iraqi officials knew it had been surreptitiously looted in 1995 and broken into parts to be smuggled out of the country. The pieces of the lamassu’s head were successfully retrieved and are currently exhibited in the Iraq Museum in Baghdad.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024