Home | Category: Economic, Agriculture and Trade

AGRICULTURE IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA

People on the Tigres and Euphrates learned how to domesticate plants and animals about 10,000 years ago. The world's first wheat, oats, barely and lentils evolved from wild plants found in Iraq. Mesopotamia was ideally suited for agriculture. It was flat and treeless. There was lots of sun and no killing frosts and plenty of water from two mighty rivers that flooded every spring, depositing nutrient-rich silt on the already fertile soil. Major crops included barley, dates, wheat, lentils, peas, beans, olives, pomegranates, grapes, vegetables. Pistachios were grown in royal gardens in Babylonia.

Morris Jastrow said: “The population was largely agricultural, but as the cities grew in size, naturally, industrial pursuits and commercial activity increased. Testimony to brisk trading in fields and field products, in houses and woven stuffs, in cattle and slaves is furnished by the large number of business documents of all periods from the earliest to the latest, embracing such a variety of subjects as loans, rents of fields and houses, contracts for work, hire of workmen and slaves, and barter and exchange of all kinds. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

Agriculture was carried on there either by free laborers, or by the slaves of the private land-owners. Where the land belonged to priests, it was of course usually the temple slaves who tilled it. The fertility of the Babylonian soil was remarkable. Grain, it was said, gave a return of two hundred for one, sometimes of three hundred for one. Herodotus, or the authority he quotes, grows enthusiastic upon the subject. “The leaf of the wheat and barley,” he says, “is as much as three inches in width, and the stalks of the millet and sesamum are so tall that no one who has never been in that country would believe me were I to mention their height.” [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

RELATED ARTICLES:

FARMING IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com ;

LIVESTOCK, SHEEP AND HERDING IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com ;

HAMMURABI'S CODE OF LAWS ON FARMING, HERDING AND AGRICULTURAL LAND africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Bulletin on Sumerian Agriculture Vol. III” by Sumerian Agriculture Group (1987) Amazon.com;

“The Dawn of Agriculture and the Earliest States in Genesis 1-11" (Routledge Studies in the Biblical World) by Natan Levy (2023) Amazon.com;

“A Thousand Years of Farming: Late Chalcolithic Agricultural Practices at Tell Brak in Northern Mesopotamia (BAR International) by Mette Marie Hald (2008) Amazon.com;

“Climate Change in the Middle East and North Africa: 15,000 Years of Crises, Setbacks, and Adaptation” by William R. Thompson and Leila Zakhirova (2021) Amazon.com;

“Challenging Climate Change: Competition and Co-operation Among Pastoralists and Agriculturalists in Northern Mesopotamia (c.3000-1600 BC)” (2009) by Arne Wossink Amazon.com;

“Climate, Environment and Agriculture in Assyria: In the 2nd Half of the 2nd Millennium BCE” (Studia Chaburensia) by Herve Reculeau (2011) Amazon.com;

“Agriculture and the State in Ancient Mesopotamia: An Introduction to Problems of Land Tenure” by Maria deJ. Ellis (1976) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Ancient Agriculture (Blackwell) by David Hollander and Timothy Howe (2020) Amazon.com;

“Date Culture in Ancient Babylonia” by August Henry (1923) Amazon.com;

“Irrigation of Mesopotamia” by William Willcocks (1917) Amazon.com;

“The Neolithic Revolution in the Near East: Transforming the Human Landscape”

by Alan H. Simmons and Dr. Ofer Bar-Yosef (2011) Amazon.com;

"First Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies" by Peter Bellwood (2004) Amazon.com;

“Birth Gods and Origins Agriculture” by Jacques Cauvin (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Origins of Agriculture: An International Perspective” by C. Wesley Cowan, Paul Minnis, et al. (2006) Amazon.com;

“Domestic Animals of Mesopotamia” (2 vols.) -- BSA vols. 7-8

by Nicholas Postgate and Marvin Powell (1993) Amazon.com;

“Domestic Animals of Mesopotamia Part II (Bulletin on Sumerian Agriculture, VIII) by unknown author Amazon.com;

“The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity” by David Graeber and David Wengrow (2021) Amazon.com;

“Plant Domestication and the Origins of Agriculture in the Ancient Near East”

by Shahal Abbo, Avi Gopher (2022) Amazon.com;

“Behavioral Ecology and the Transition to Agriculture” by Douglas J. Kennett and Bruce Winterhalder (2006) Amazon.com;

“Life in Neolithic Farming Communities: Social Organization, Identity, and Differentiation” by Ian Kuijt (2006) Amazon.com;

“Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History” by Nicholas Postgate (1994) Amazon.com;

“Economy and Society of Ancient” Mesopotamia (Studies in Ancient Near Eastern Records) by Steven Garfinkle and Gonzalo Rubio (2025) Amazon.com;

“Economic Life at the Dawn of History in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt: The Birth of Market Economy in the Third and Early Second Millennia BCE” by Refael (Rafi) Benvenisti and Naftali Greenwood (2024) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Stephen Bertman (2002) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Babylon and Assyria” by Georges Contenau (1954) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

Agricultural Regions and Weather of Mesopotamia

Modern Iraq is divided into four principal regions: 1) an upper plain between the Tigris and Euphrates which stretches from north and west of Baghdad to the Turkish border and is regarded as the most fertile part of the country; 2) the lower plain between the Tigris and Euphrates, which extends from north and west of Baghdad to Persian Gulf and embraces a large area of marshes, swamps and narrow waterways; 3) mountains in the north and northeast along the Turkish and Iranian borders; 4) and vast deserts which spread south and west of the Euphrates to the borders of Syria, Jordan and Saudi Arabia.

The Tigris and Euphrates are two of the world’s most famous rivers. The Tigris River is about 1,200 miles (1950 kilometers) long and originates in the mountains of southern Turkey and enters Iraq near the spot where Iraq, Turkey and Syria meet. The Euphrates is about 1,300 miles (2100 kilometers) long and originates in the mountains of central Turkey and flows a considerable distance through Turkey and Syria before it enters western Iraq.

Silt from the Tigris and Euphrates rivers has built a long, fertile alluvial plain, and a large delta and vast marshes. The area around the rivers has been heavily irrigated since Mesopotamian times. In the north the rivers usually stay within their banks. In the south and east the rivers have traditionally flooded in the spring. Some barriers have been built to prevent this from happening near populated areas.

The weather in Mesopotamia was no doubt similar to the weather in Iraq today. In Iraq the weather in Iraq varies according to elevation and location but generally is mild in the winter, very hot in the summer and dry most of the year except for a brief rainy period in the winter. Most of the country has a desert climate. The mountainous areas have temperate climates. Winter and to a lesser extent spring and autumn are pleasant in much of the country.

Precipitation is generally scarce in most of the Iraq and tends to fall between November and March, with January and February generally being the rainiest months. The heaviest precipitation usually falls in the mountains and on the windward western sides of the mountains. Iraqi receives relatively little rain because the mountains in Turkey, Syria and Lebanon block the moisture carried by winds from the Mediterranean Sea. Very little rain comes in from the Persian Gulf.

See Separate Articles: GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE OF MESOPOTAMIA AND LINKS TO PEOPLE THERE NOW africame.factsanddetails.com ; MESOPOTAMIA: THE PLACE, CIVILIZATIONS, THE FERTILE CRESCENT africame.factsanddetails.com

Development of Agriculture

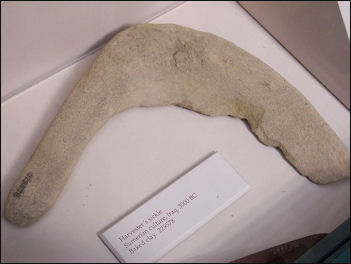

Clay sickle model from Sumer Agriculture began around 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. Considered the most important human advance after the control of fire and the creation of tools, it allowed people to settle in specific areas and freed them from hunting and gathering. According to the Bible, Cain and Abel, the sons of Adam and Eve, developed agriculture and domesticated animals, “Now Abel was a keeper of sheep, and Cain a tiller of the ground,” the Bible reads.

The first documented agriculture occurred 11,500 year ago in what Harvard archaeologist Ofer Ban-Yosef calls the Levantine Corridor, between Jericho in the Jordan Valley and Mureybet in the Euphrates Valley. At Mureybit, a site on the banks of the Euphrates, seeds from an uplands area — where the plants from the seeds grow naturally — were found and dated to 11,500 years ago. An abundance of seeds from plants that grew elsewhere found near human sites is offered as evidence of agriculture.

Early agriculture is most famously associated with the Fertile Crescent, an arc of land that extends from southern Turkey into Iraq and Syria and finally to Israel and Lebanon. Seeds of 10,000-year-old cultivated wheat have been discovered at sites in Iraq and northern Syria. The region also produced the first domesticated sheep, goats, pigs and cattle.

See Separate Articles ORIGIN AND EARLY HISTORY OF AGRICULTURE factsanddetails.com ; IMPORTANT EARLY DEVELOPMENTS IN AGRICULTURE: PLOUGHING, FERTILIZER AND IRRIGATION factsanddetails.com ; FIRST GRAINS AND EARLIEST CROPS: BARLEY, EINKORN AND EMMER WHEAT, MILLET, SORGHUM, RICE AND CORN factsanddetails.com ;

Crops in Ancient Mesopotamia

Major crops included barley, dates, wheat, lentils, peas, beans, olives, pomegranates, grapes, vegetables. Pistachios were grown in royal gardens in Babylonia. Mesopotamia was at least one of the origin places of cultivated cereals. Wild wheat has been found growing in the area of Hit, in the Al Anbar region on the Euphrates Rivers. The dissemination of wheat goes back to a remote epoch. Like barley, it is met with in the tombs of that prehistoric population of Egypt which still lived in the neolithic age and whose later remains are coeval with the first Pharaonic epoch. The fact throws light on the antiquity of the intercourse which existed between the Euphrates and the Nile, and bears testimony to the influence already exerted on the Western world by the culture of Babylonia. We have, indeed, no written records which go back to so distant a past; it belongs, perhaps, to an epoch when the art of writing had not as yet been invented. But there was already civilization in Babylonia, and the elements of its future social life were already in existence. Babylonian culture is immeasurably old. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The first domesticated crop is believed to have been einkorn wheat, a kind of nourishing grass adapted from a wild species of grass native to the Karacadag mountains near Diyarbakir in southwestern Turkey first cultivated around 11,000 years ago. Scientists deduced this by examining the DNA of modern strains of einkorn wheat and found the were more similar to einkorn wheat grown in the Karacadag mountains than in other places. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, November 20, 1997]

Emmer wheat, rye and barley were cultivated around the same time, and is difficult to say which was cultivated first. Emmer wheat and another wheat strain from the Caspian Sea are thought to be the first bread wheats. Emmer wheat is a wild grass. It is thought to have been singled out because its seeds stay attached to the stem significantly longer than that of other grasses.

Dates are the fruit of a desert palm tree. There are 220 kinds of dates, or which about 20 are commercially viable. A popular food in the Middle East, they and found in abundance in the desert and around oases. Many parts of the Middle East would be uninhabitable were it not for date palms. It is one of the few crops that grows in the desert. Date palms have been described as the “tree of life.”

See Separate Articles: DATES AND DATE PALM CULTIVATION factsanddetails.com FIRST GRAINS AND CROPS: BARLEY, WHEAT, MILLET, SORGHUM, RICE AND CORN factsanddetails.com

“How Grain Came to Sumer”

eikorn Triticum The story “How Grain Came from Sumer” goes: “Men used to eat grass with their mouths like sheep. In those times, they did not know grain, barley or flax. An brought these down from the interior of heaven. Enlil lifted his gaze around as a stag lifts its horns when climbing the terraced ...... hills. He looked southwards and saw the wide sea; he looked northwards and saw the mountain of aromatic cedars. Enlil piled up the barley, gave it to the mountain. He piled up the bounty of the Land, gave the innuha barley to the mountain. He closed off access to the

wide-open hill. He ...... its lock, which heaven and earth shut fast , its bolt, which .....[Source: J.A. Black, G. Cunningham, E. Robson, and G. Zlyomi 1998, 1999, 2000, Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford University, piney.com]

“Then Ninazu ......, and said to his brother Ninmada: "Let us go to the mountain, to the mountain where barley and flax grow;...... the rolling river, where the water wells up from the earth. Let us fetch the barley down from its mountain, let us introduce the innuha barley into Sumer. Let us make barley known in Sumer, which knows no barley."

Ninmada, the worshipper of An, replied to him: "Since our father has not given the command, since Enlil has not given the command, how can we go there to the mountain? How can we bring down the barley from its mountain? How can we introduce the innuha grain into Sumer? How can we make barley known in Sumer, which knows no barley? "Come, let us go to Utu of heaven, who as he lies there, as he lies there, sleeps a sound sleep, to the hero, the son of Ningal, who as he lies there sleeps a sound sleep." He raised his hands towards Utu of the seventy doors.”

Prices and Payments for Crops in Ancient Mesopotamia

The price of grain varied from year to year. In years of scarcity the price rose; when the crops were plentiful it necessarily fell. To a certain extent the annual value was equalized by the large exportation of grain to foreign countries, to which reference is made in many of the contract-tablets; the institution of royal or public store-houses, moreover, called sutummê, tended to keep the price of it steady and uniform. Nevertheless, bad seasons sometimes occurred, and there were consequent fluctuations in prices. This was more especially the case as regards the second staple of Babylonian food and standard of value — dates. These seem to have been mostly consumed in Babylonia itself, and, though large quantities of them were accumulated in the royal storehouses, it was upon a smaller scale than in the case of the grain. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Hence we need not be surprised if we find that while in the seventh year of Nebuchadnezzar a shekel was paid for 1-1/3 ardebs of dates, or about a halfpenny a quart, in the thirtieth year of the same reign the price had fallen to one-twenty-fifth of a penny per quart. A little later, in the first year of Cambyses, 100 gur of dates was valued at 2½ shekels (7s. 6d.), the gur containing 180 qas, which gives 2d. per each qa, and in the second year of Cyrus a receipt for the payment of “the workmen of the overseer” states that the following amount of dates had been given from “the royal store-house” for their “food” during the month Tebet: “Fifty gur for the 50 workmen, 10 gur for 10 shield- bearers, 2 gur for the overseer, 1 gur for the chief overseer; in all, 63 gurs of dates.” It was consequently calculated that a workman would consume a gur of dates a month, the month consisting of thirty days. About the same period, in the first year of Cyrus, after his conquest of Babylon, we hear of two men receiving 2 pi 30 qas (102 qas) of grain for the month Tammuz. Each man accordingly received a little over a qa a day, the wage being practically the same as that paid by Nubtâ to the slave.

cuneiform tablet with flour and bread distributions

On the other hand, a receipt dated in the fifteenth year of Nabonidos is for 2 pi (72 qas) of grain, and 54 qas of dates were paid to the captain of a boat for the conveyance of mortar, to serve as “food” during the month Tebet. As “salt and vegetables” were also added, it is probable that the captain was expected to share the food with his crew. A week previously 8 shekels had been given for 91 gur of dates owed by the city of Pallukkatum, on the Pallacopas canal, to the temple of Uru at Sippara, but the money was probably paid for porterage only. At all events, five years earlier a shekel and a quarter had been paid for the hire of a boat which conveyed three oxen and twenty-four sheep, the offering made by Belshazzar “in the month Nisan to Samas and the gods of Sippara,” while 60 qas of dates were assigned to the two boatmen for food. This would have been a qa of dates per diem for each boatman, supposing the voyage was intended to last a month. In the ninth year of Nabonidos 2 gur of dates were given to a man as his nourishment for two months, which would have been at the rate of 6 qas a day. In the thirtysecond year of the same reign 36 qas of dates were valued at a shekel, or a penny a qa.

In the older period of Babylonian history prices were reckoned in grain, and, as might be expected, payment was made in kind rather than in qas of oil, though valued at 20 shekels of silver, were actually bought with “white Kurdish slaves,” it being stipulated that if the slaves were not forthcoming the purchaser would have to pay for the oil in cash. A thousand years later, under Marduk-nadin-akhi, cash had become the necessary medium of exchange. A cart and harness were sold for 100 shekels, six riding-horses for 300 shekels, one “ass from the West” for 130 shekels, one steer for 30 shekels, 34 gur 56 qas of grain for 137 shekels, 2 homers 40 qas of oil for 16 shekels, two long-sleeved robes for 12 shekels, and nine shawls for 18 shekels. coin. In the reign of Ammi-zadok, for instance, 3 homers 24 From this time forward we hear no more of payment in kind, except where wages were paid in food, or where tithes and other offerings were made to the temples. Though the current price of wheat continued to fix the market standard of value, business was conducted by means of stamped money. The shekel and the maneh were the only medium of exchange. There are numerous materials for ascertaining the average prices of commodities in the later days of Babylonian history. We have already seen what prices were given for sheep and wool, as well as the cost of some of the articles of household use.

In the thirty-eighth year of Nebuchadnezzar 100 gur of wheat were valued at only 1 maneh — that is to say, the qa of wheat was worth only the hundredth part of a shilling — while at the same time the price of dates was exactly one-half that amount. On the other hand, in the fourth year of Cambyses 72 qas of sesame were sold at Sippara for 6½ shekels, or 19s. 6d. This would make the cereal worth approximately 1½d. a quart, the same price as that at which it was sold in the twelfth year of Nabonidos. In the second year of Nergal-sharezer twenty-one strings of onions fetched as much as 10 shekels, and a year later 96 shekels were given for onion bulbs for planting.

Irrigation in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamians developed irrigation agriculture. To irrigate the land, the earliest inhabitants of the region drained the swampy lands and built canals through the dry areas. This had been done in other places before Mesopotamian times. What made Mesopotamia the home of the first irrigation culture is that the irrigation system was built according to a plan, and an organized work force was required to keep the system maintained. Irrigation system began on a small-scale basis and developed into a large scale operation as the government gained more power.

Mesopotamia was originally swampy in some areas and dry in others. The climate was too hot and dry in most places to raise crops without some assistance. Archaeologists have found 3,300-year-old plow furrows with water jars still lying by small feeder canals near Ur in southern Iraq.

The Sumerians initiated a large scale irrigation program. They built huge embankments along the Euphrates River, drained the marshes and dug irrigation ditches and canals. It not only took great amount of organized labor to build the system it also required a great amount of labor to keep it maintained. Government and laws were created distribute water to make sure the operation ran smoothly.

Claude Hermann and Walter Johns wrote in the Encyclopedia Britannica:“Irrigation was indispensable. If the irrigator neglected to repair his dyke, or left his runnel open and caused a flood, he had to make good the damage done to his neighbours' crops, or be sold with his family to pay the cost. The theft of a watering-machine, water-bucket or other agricultural implement was heavily fined. [Source: Claude Hermann Walter Johns, Babylonian Law — The Code of Hammurabi. Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910-1911]

The early Mesopotamian civilizations are believed to have fallen because salt accruing from irrigated water turned fertile land into a salt desert. Continuous irrigation raised the ground water, capillary action — the ability of a liquid to flow against gravity where liquid spontaneously rises in a narrow space such as between grains of sand and soil — brought the salts to the surface, poisoning the soil and make it useless for growing wheat. Barley is more salt resistant than wheat. It was grown in less damaged areas. The fertile soil turned to sand by drought and the changing course of the Euphrates that today is several miles away from Ur and Nippur.

See Separate Article: IRRIGATION IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com

Mesopotamian irrigation

Mesopotamian Laws Related to Agriculture

Morris Jastrow said: “The farming of lands for the benefit of temples or for lay owners, with a return of a share of the products to the proprietors, was naturally one of the most common commercial transactions in a country like the Euphrates Valley, so largely dependent upon agriculture. Complications in such transactions would naturally ensue, and it is interesting to observe with what regard for the ethics of the situation they are dealt with in the Code. If a tenant fail to produce a crop through his own fault, he is obliged, of course, to reimburse the proprietor, and as a basis of compensation, the yield of the adjoining fields is taken as a standard. If he have failed, however, to cultivate the field, he is not only obliged to compensate the owner according to the proportionate amount produced in that year in adjoining fields, but must, in addition, plough and harrow the property before returning it to the owner, besides furnishing ten measures—about twenty bushels—of grain for each acre of land. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“In case of a failure of the crops, or a destruction by act of God, no responsibility attaches to the tenant, but if the owner had already received his share beforehand, and then through a storm or an inundation the yield is spoiled, the loss must be borne by the tenant. In subletting the tilling of fields as part payment for debt, it is stipulated that the original proprietor must first be settled with, and after that the second lessee, who shall receive in kind the amount of his debts plus the usual interest. The ethical principle is, therefore, similar to that applying in our own days to first and second mortgages.

“The owner of a field is responsible for damage done to his neighbours’ property through neglect on his part—for example, through his failure to keep the dikes in order, or through his cutting off the water supply from his neighbour. A shepherd who allows his flocks to pasture in a field without permission of the owner is fined to the extent of twenty measures of grain for each ten acres. What is left of the pasturage also belongs to the owner. The same care, with due regard to the ethics of the situation, is exercised in regulating the relation between a merchant and his agent. The latter is, of course, responsible for goods entrusted to him, including damage to them through his fault, but if they are stolen or forcibly taken from him—after swearing an oath to that effect—he is free from further responsibility. Neglect to carry out instructions in connection with a commission entails a fine threefold the value involved, but, on the other hand, if the merchant tries to defraud his agent, he pays a fine of sixfold the amount involved.”

Hammurabi's Code of Laws on Agriculture

The Babylonian king Hammurabi (1792-1750 B.C.) is credited with producing the Code of Hammurabi, the oldest surviving set of laws. Recognized for putting eye for an eye justice into writing and remarkable for its depth and judiciousness, it consists of 282 case laws with legal procedures and penalties. Many of the laws had been around before the code was etched in the eight-foot-highin black diorite stone that bears them. Hammurabi codified them into a fixed and standardized set of laws. [Source: Translated by L. W. King]

40) He may sell field, garden, and house to a merchant (royal agents) or to any other public official, the buyer holding field, house, and garden for its usufruct.

41) If any one fence in the field, garden, and house of a chieftain, man, or one subject to quit-rent, furnishing the palings therefor; if the chieftain, man, or one subject to quit-rent return to field, garden, and house, the palings which were given to him become his property.

42) If any one take over a field to till it, and obtain no harvest therefrom, it must be proved that he did no work on the field, and he must deliver grain, just as his neighbor raised, to the owner of the field.

43) If he do not till the field, but let it lie fallow, he shall give grain like his neighbor's to the owner of the field, and the field which he let lie fallow he must plow and sow and return to its owner.

44) If any one take over a waste-lying field to make it arable, but is lazy, and does not make it arable, he shall plow the fallow field in the fourth year, harrow it and till it, and give it back to its owner, and for each ten gan (a measure of area) ten gur of grain shall be paid.

45) If a man rent his field for tillage for a fixed rental, and receive the rent of his field, but bad weather come and destroy the harvest, the injury falls upon the tiller of the soil.

46) If he do not receive a fixed rental for his field, but lets it on half or third shares of the harvest, the grain on the field shall be divided proportionately between the tiller and the owner.

See Separate Article: HAMMURABI'S CODE OF LAWS ON FARMING, HERDING AND AGRICULTURAL LAND africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024