ASHURBANIPAL

Ashurbanipal by George Stuart

Ashurbanipal (r.668-627 B.C.) was the last great Assyrian king. The ruler of ancient Assyria when it was at its military and cultural peak, he defeated the Elamites in the east and extended the Assyrian empire to its greatest extent. David Giles of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga wrote: He is known in Greek writings as Sardanapalus and as Asnappeer or Osnapper in the Bible. Through military conquests Ashurbanipal also expanded Assyrian territory and its number of vassal states. However, of far greater importance to posterity was Ashurbanipal's establishment of a great library in the city of Nineveh. The military and territorial gains made by this ruler barely outlived him but the Library he established has survived partially intact. [Source: David Giles, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, Library of King Ashurbanipal Web Page]

Morris Jastrow said: “Shortly before the end, however, Assyria witnessed the most brilliant reign in her history—that of Ashurbanapal (668-626 B.C.)who was destined to realise the dreams of his predecessors, Sargon, Sennacherib, and Esarhaddon; of whom all four had been fired with the ambition to make Assyria the mistress of the world. Their reigns were spent in carrying on incessant warfare in all directions. During Ashurbanapal’s long reign, Babylonia endured the humiliation of being governed by Assyrian princes. The Hittites no longer dared to organise revolt, Phoenicia and Palestine acknowledged the sway of Assyria, and the lands to the east and northeast were kept in submission. From Susa, the capital of Elam, Ashurbanapal carried back in triumph a statue of Nana,—the Ishtar of Uruk,—which had been captured over 1600 years before, and—greatest triumph of all—the Assyrian standards were planted on the banks of the Nile, though the control of Egypt, as was soon shown, was more nominal than real. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

“Thus the seed of dominating imperialism, planted by the old Sargon of Agade, had borne fruit. But the spirit of Hammurabi, too, hovered over Assyria. Ashurbanapal was more than a conqueror. Like Hammurabi, he was a promoter of culture and learning. It is to him that we owe practically all that has been preserved of the literature produced in Babylonia. Recognising that the greatness of the south lay in her intellectual prowess, in the civilisation achieved by her and transferred to Assyria, he sent scribes to the archives, gathered in the temple-schools of the south, and had copies made of the extensive collections of omens, oracles, hymns, incantations, medical series, legends, myths, and religious rituals of all kinds that had accumulated in the course of many ages. Only a portion, alas! of the library has been recovered through the excavations of Layard and Rassam (1849-1854) and their successors on the site of Ashurbanapal’s palace at Nineveh in which the great collection was stored.”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“I Am Ashurbanipal: King of the World, King of Assyria” by Gareth Brereton (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Library of Ancient Wisdom: Mesopotamia and the Making of History” by Laura Selena Wisnom (2025) Amazon.com;

“The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal (668–631 BC)” by Joshua Jeffers and Jamie Novotny (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Annals of Ashurbanapal” (Classic Text) Amazon.com;

“History of Assurbanipal”, Translated From the Cuneiform Inscriptions (Classic Reprint) Amazon.com;

“Assyria: The Rise and Fall of the World's First Empire” by Eckart Frahm (2023) Amazon.com;

“Assyrian Empire: A History from Beginning to End” by History Hourly (2019) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Assyria” by Eckart Frahm (2017) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction” by Karen Radner (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Might That Was Assyria” by H. W. F. Saggs (1984) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Assyria” by James Baikie (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: an Enthralling Overview of Mesopotamian History (2022) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: a Captivating Guide (2019) Amazon.com;

“A History of the Ancient Near East” by Marc Van De Mieroop (2003) Amazon.com;

Ashurnasirpal’s Early Life

Ashurbanipal was first trained for priestly position and only made king after his elder brother was kidnapped and killed by the Babylonians. According to National Geographic: He was born sometime around 685 B.C., to King Esarhaddon and one of his three wives. When Ashurbanipal was 12 or 13, Esarhaddon began preparing for his succession. The eldest son died before reaching maturity. To avoid squabbling and palace intrigue, the king named both Ashurbanipal and his older half brother, Shamash-shum-ukin, as crown princes. He assigned Shamash-shum-ukin to rule the city of Babylon, which was under Assyrian control. Ashurbanipal stayed in the capital. [Source: National Geographic, National Geographic,, August 25, 2022]

Crown prince Ashurbanipal was trained in military affairs, diplomacy, and administration. He was also tutored in history, literature, archery, hunting, and horsemanship. He mastered the teachings of the priests and scribes and learned to read Sumerian and Akkadian. Possibly by the intervention of the queen mother, his grandmother Naqi’a-Zakutu, he was given heavy responsibilities dealing with nobles and the royal court, controlled governmental appointments and supervised building projects within the Assyrian homeland, and even ran the imperial intelligence service.

His mastery of these responsibilities, his demonstrated statesmanship, and his detailed reports to his father led Esarhaddon to leave Ashurbanipal in charge of affairs when he left on a military expedition to Egypt. It was his last. Esarhaddon died in 669 B.C. at Harran. The relationships Ashurbanipal had forged with nobles and the military smoothed the transition of power to him after his father’s demise.

Ashurnasirpal’s Military Campaigns

According to National Geographic:: Ashurbanipal continued the fights of his father, and like many of his predecessors, he launched his own military campaigns to consolidate his position as king. Where he stood out was in the significance and scope of his military victories. He chalked up successful conquests: against Thebes, capital of Upper Egypt in 664 B.C., and against the Iranian kingdom of Elam at the Battle of Til-Tuba in 653 B.C. He put down a revolt by his brother Shamash-shum-ukin in Babylon in 648 B.C. and sacked the city of Susa in 647 B.C. [Source: National Geographic, National Geographic,, August 25, 2022]

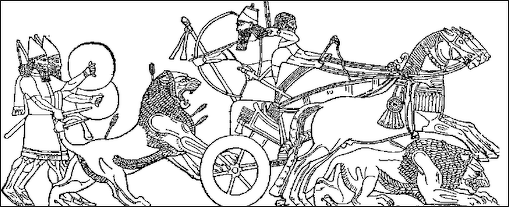

The Rassam Cylinder from 643 B.C. contains records of Ashurbanipal’s nine military campaigns. Many of the reliefs in the throne room depicted battle scenes, commemorating Ashurbanipal’s great military victories, including the campaigns against Babylon, Elam, Egypt, and the Arab tribes. Although Ashurbanipal rarely accompanied his soldiers onto the battlefield, he created a powerful iconography through these elaborate reliefs that would preserve a legacy as a great military leader.

Ashurbanipal succeeded Sennacherib (705 to 681 B.C.) Sennacherib’s designated successors were Ashurbanipal and his brother Shamash-shum-uk-îm. For 17 years they ruled the Assyrian empire side by side — Ashurbanipal from Nineveh and Shamash-shum-uk-îm from Babylon. However, in 652, war broke out between the two brothers. According to Aaron Skaist: After four years of bloody warfare, Ashurbanipal emerged victorious, but at a heavy price. The Pax Assyriaca had been irreparably broken, and the period of Assyrian greatness was over. The last 40 years of Assyrian history were marked by constant warfare in which Assyria, in spite of occasional successes, was on the defensive. At the same time the basis for a Babylonian resurgence was being laid even before the final Assyrian demise. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

Ashurnasirpal’s Achievements and Boasts

Ashurbanipal was unique among rulers in ancient Mesopotamia in that could read and write and seems to have enjoyed literature and was proud of his literacy. He founded the world’s first serious library. Archaeologists found the library and unearthed good copies of the epic of Gilgamesh and Mesopotamia poetry there.

According to National Geographic: From inscriptions on palace walls and incisions in cuneiform tablets, he was styled “Great King, the Mighty King, King of Assyria, King of Sumer and Akkad, the King of the World.” Those titles might seem exaggerated today, but for his time, they just might have been warranted. For almost 40 years, Ashurbanipal reigned over the Assyrian Empire and ruled over the largest kingdom of its time—and perhaps the greatest up to the seventh century B.C. Assyria’s holdings extended from the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf, and from Egypt to the mountains of southeastern Turkey. The Assyrians were certainly aware that beyond lay other lands, peoples, tribes, and cities, but they referred to what was outside their realms as “empty lands:” territories of no interest, occupied by uncivilized people with nothing of value to offer. [Source: National Geographic, National Geographic,, August 25, 2022]

Ashurbanipal claimed in inscriptions that he was the most exceptional Assyrian king. Unlike most ancient leaders, his claim to greatness was not based solely on military prowess. While his victories are certainly featured—lands conquered and enemies subdued—Ashurbanipal boasted the most of his intellectual gifts: “I, Ashurbanipal, learned the wisdom of Nabu [the god of writing], laid hold of scribal practices of all the experts, as many as there are.”

Inscriptions refer to his ability to interpret ancient texts, solve complex mathematical problems, and debate theological questions with his court’s most renowned sages and soothsayers. In one text Ashurbanipal styles himself as a disciple of Adapa, the first of the seven Mesopotamian sages, endowed with intelligence by Ea, god of wisdom. The legendary Adapa lived before the ancient flood that, according to Babylonian myth, had devastated the cities of Mesopotamia.

Despite Adapa’s omniscience, he never acquired divine status because he refused to accept the bread and water of eternal life offered to him by Anu the sky god. Because of his refusal, Adapa and all humanity remained mortal. Linking himself to Adapa, a figure central to Assyrian founding myths, Ashurbanipal aligned himself with Assyria’s revered ancestors and emphasized his skills at deciphering ancient Sumerian tablets.

Ashurbanipal’s Library

Ashurbanipal's library was not the first library of its kind but it was one of the largest and one of the ones to survive to the present day. Discovered in the late 19th century, most of it is now in the possession of the British Museum or the Iraq Department of Antiquities. A collection of 20,000 to 30,000 cuneiform tablets containing approximately 1,200 distinct texts remains for scholars to study today.

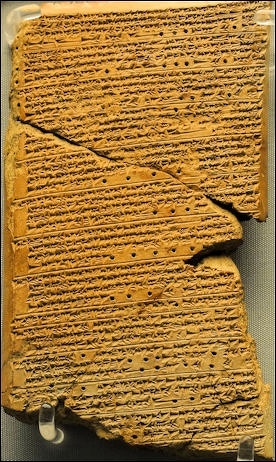

Venus tablet from Ashurbanipal’s Library

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: While working at the newly rediscovered site of Nineveh in northern Iraq in 1850, a team directed by Assyriologist Austen Henry Layard was exploring the ruins of a Neo-Assyrian (ca. 883–609 B.C.) palace built sometime after 700 b.c. when they came across rooms filled with thousands of clay tablets piled more than a foot high. The tablets were inscribed with the small wedge-shaped symbols known as cuneiform writing. They belonged to a library once located on the palace’s upper floor, which had come crashing down when the complex was ransacked and burned in 612 B.C. Rather than destroying the tablets, however, the fire baked, hardened, and preserved them. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, Features July/August 2024]

This collection of written works was assembled from around the empire by Ashurbanipal (reigned 668–631 B.C.), who was both a formidable military leader and an avid scholar. Texts that document the king’s life boast of his education and the depth of his knowledge. He even commissioned relief sculptures that portray him with writing styluses tucked into his belt. These implements were used to create cuneiform tablets and were symbols of Ashurbanipal’s erudition. “There have always been collections of texts, going back millennia, but what is different about Ashurbanipal is quite how much he’s got,” says curator Jonathan Taylor of the Department of the Middle East at the British Museum. “He seems to have wanted to collect a copy of everything.”

Between the 1850s and 1930s, around 32,000 clay tablets from the library were uncovered. Among them were official documents such as foreign correspondence and administrative records, literary texts including the ancient Mesopotamian poem the Epic of Gilgamesh, and various other works on subjects ranging from astronomy to warfare. Ashurbanipal was particularly interested in collecting texts about divination and how to read omens and communicate with the gods. “The majority of the material there has to do with predicting the future,” says Taylor. “Portent was the ancient equivalent of science, and what the king is collecting has very much to do with power and controlling the empire.”

Morris Jastrow said: “About 20,000 fragments of clay bricks have found their way to the British Museum, but it is safe to say that this represents less than one half of the extent of the great library which Ashurbanapal had accumulated. His immediate purpose in doing so was to emphasise by an unmistakable act that Assyria had assumed the position of Babylonia, not only as an imperial power and as a stronghold of culture, but also as the great religious centre. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

Assembling Ashurbanipal’s Library

According to National Geographic: Ashurbanipal was proud of his ability to read and write, and portrayed himself bearing both weapons and a stylus. Inscription L, found in Nineveh, proudly showcases his intellectual abilities: I learnt the lore of the wise sage Adapa, the hidden secret of all scribal art. I can recognize celestial and terrestrial omens (and) discuss (them) in the assembly of the scholars. I can deliberate upon (the series) “(If) the liver is a mirror (image) of heaven” with able experts in oil divination. I can solve complicated multiplications and divisions which do not have an (obvious) solution. I have studied elaborate composition(s) in obscure Sumerian (and) Akkadian which are difficult to get right. I have inspected cuneiform sign(s) on stones from before the flood. [Source: National Geographic, National Geographic,, August 25, 2022]

Ever keen to present himself as an intellectual, Ashurbanipal set out to create what became his most important legacy: the great royal library at Nineveh. There he gathered the records of Mesopotamian knowledge, from literary texts to medicine, magic, and divination. The process of building up the Assyrian library was long and complex. The king ordered his officials to seize the holdings of all the libraries of Assyria and Babylon. In this way, he acquired the private library of Nabu-zuqup-kenu, former scribe of Sargon II and Sennacherib, which included a large collection of divination texts based on astronomical and meteorological observations.

It was more difficult to raid the Babylonian libraries than the Assyrian ones since the collections in Babylon were closely guarded by scribes and priests in the temples. When the relationship between Ashurbanipal and his brother Shamash-shum-ukin, crown prince of Babylon, was amicable, Ashurbanipal asked Babylonian sages for copies of the most important texts in their keeping. However, after the Babylonian revolt of 652 B.C., Ashurbanipal’s policy became much more aggressive, and he simply confiscated documents at will. There is evidence that in 647 B.C., when the Babylonian revolt had already been put down, 1,469 cuneiform tablets were added to the Nineveh library, brought directly from Babylon.

Ashurbanipal devoted much time and attention to creating his library. Sometimes he supervised the copying process in person, even suggesting modifications according to his taste. This policy ran counter to scribal practice; texts were thought to contain ancient knowledge imparted by the gods or sages from former times, so temple scribes were scrupulous about not making changes. Ashurbanipal’s choice to break that rule shows that he considered himself worthy of a place among the elevated group of the seven sages.

Importance of Ashurbanipal’s Library as a Source of Information

David Giles of the University of Tennessee wrote: “The importance of Ashurbanipal's Library can not be overstated. It was buried by invaders centuries before the famous library at Alexandria was established and gives modern historians much information about the peoples of the Ancient Near East. The ancient Sumerian "Epic of Gilgamesh" and a nearly complete list of ancient Near Eastern rulers among other priceless writings were preserved in Ashurbanipal's palace library at Nineveh. Ashurbanipal's accomplishments are also of great importance to scholars of library history. As a scholar Ashurbanipal reached greatnesss. [Source: David Giles, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, Library of King Ashurbanipal Web Page]

“Though this library was not the first of its kind, it was one of the largest and the first library modern scholars can document as having most or even all of the attributes one expects to find in a modern library. Like a modern library this collection was spread out into many rooms according to subject matter. Some rooms were devoted to history and government, others to religion and magic and still others to geography, science, poetry, etc. Ashurbanipal's collection even held what could be called classified government materials. The findings of spies and secret affairs of state were held secure from access in deep recesses of the palace much like a modern government archive.

“Each group of tablets contained a brief citation to identify the contents and each room contained a tablet near the door to classify the general contents of each room in Ashurbanipal's library. The actual cataloging activities under Ashurbanipal's direction would not be seen in Europe for centuries. Partially through military conquests and partially through the employment of numerous scribes there was significant effort placed into what modern librarians would call collection development. Thus, centuries before the library at Alexandria, a library with many of the characteristics of a modern institution was in existence.”

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: While the texts of Ashurbanipal’s library have been crucial in providing a deeper understanding of Neo-Assyrian life 2,700 years ago—before the library was discovered, most knowledge about the Neo-Assyrians came from the Old Testament or classical sources—there is still much that researchers hope to learn. The vast majority of the tablets remain untranslated. Most were found broken and mixed together, making it very difficult to reassemble them properly. “It’s not only like putting together a jigsaw puzzle, it’s like assembling 5,000 jigsaw puzzles simultaneously that someone has knocked off the shelf and the pieces have all scattered,” Taylor says. “We don’t have the box anymore, so we don’t even know what the picture is supposed to look like. It’s a real challenge.” [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, Features July/August 2024]

Over the last 170 years, only about 35 texts on average have been successfully pieced back together and translated each year. At that rate, it would take 400 more years to decipher Ashurbanipal’s entire library. However, imaging technology and artificial intelligence are speeding things up and making the process much more efficient. “Now that we have the resources,” Taylor says, “you can imagine easily that within a generation we will have solved a centuries-long problem.”

Ashurbanapal and Religion

According to National Geographic: Like his father, Ashurbanipal consulted experts who claimed to see the future. King Esarhaddon had hired Babylonian seers. Surviving texts note that Ashurbanipal regularly called on fortune-tellers. In their divination (which resembles the practice of astrology today rather than astronomy), they looked to the night skies and used celestial observation. Their texts described the sky, along with a mythological explanation of the stars and planets and of possibly ominous related phenomena. Ashurbanipal also fostered another method of augury called “extispicy,” which analyzed the viscera of freshly slaughtered sheep. Anomalies in the entrails would be used to predict the future, and detailed manuals were consulted to interpret the results. The king would also call on tablets from his massive library to interpret omens from the gods. [Source: National Geographic, National Geographic,, August 25, 2022]

Morris Jastrow said: “For Ashurbanapal, Nineveh was to be a gathering place of all the gods and goddesses of the world grouped around Ashur, just as courtiers surround a monarch whose sway all acknowledge. To gather in his capital the texts that had grown up around the homage paid in the past to these gods and goddesses in their respective centres, was his method of giving expression to his hope of centralising the worship of these deities around the great figure of Ashur. Ashur-banapal’s policy, thus, illustrates again the continued strength of the bond between culture and religion, despite the fact that in its external form the bond appeared political rather than intellectual. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

“The king’s ambition, however, had its idealistic side which must not be overlooked. The god Ashur was in some respects well adapted to become the emblem of centralised divine power, as well as of political centralisation. The symbol of the god was not, as was the case with other deities, an image in human shape, but a disc from which rays or wings proceed, a reminder, to be sure, that Ashur was in his origin a solar deity,yet sufficiently abstract and impersonal to lead men’s thoughts away from the purely naturalistic or animistic conceptions connected with Ashur. This symbol appears above the images of the kings on the monuments which they erected to themselves. It hovers over the pictures of the Assyrian armies on their march against their enemies. It was carried into the battle as a sacred palladium —a symbol of the presence of the gods as an irresistible ally of the royal armies; and the kings never fail to ascribe to the support of Ashur the victories that crowned their efforts.

“Professor Sayce has properly emphasised the influence of this imageless worship of the chief deity on the development of religious ideas in Assyria. Dependent as Assyria was to a large extent upon Babylonia for her culture, her art, and her religion, she made at least one important contribution to what she adopted from the south, in giving to Ashur a more spiritual type, as it were, than Enlil, Ninib, Shamash, Nergal, Anu, Ea, Marduk, or Nebo could ever claim. On the other hand, the limitation in the development of this more spiritual conception of divine power is marked by the disfiguring addition, to the winged disc, of the picture of a man with a bow and arrow within the circle. It was the emblem of the military genius of Assyria.

“The old solar deity as the protector of the Assyrian armies had become essentially a god of war, and the royal warriors could not resist the temptation to emphasise by a direct appeal to the eyes the perfect accord between the god and his subjects. This despiritualisation of the winged disc no doubt acted as a check on a conceivable growth of Ashur, which might have tended under more favourable circumstances towards a purer monotheistic conception of the divine government of the universe; for in his case the transference of the attributes of all the other great gods was more fully carried out than in the case of Marduk.In his capacity as a solar deity, Ashur absorbs the character of all other localised sun-gods. Myths in which Ninib, Enlil, Ea, and Marduk appear as heroes are remodelled under Assyrian influence and transferred to Ashur. We have traces of an Assyrian myth of creation in which the sphere of creator is given to Ashur.

“Ishtar, the great goddess of fertility, the mother-goddess presiding over births, becomes Ashur’s consort. The cult of the other great gods, of Shamash, Ninib, Nergal, Sin, Ea, Marduk, and even Enlil, is maintained in full vigour in the city of Ashur, and in the subsequent capital Nineveh, but these as well as other gods take on, as it were, the colour of Ashur. They give the impression of little Ashurs by the side of the great one, so entirely does the older solar deity, as the guardian of mighty Assyrian armies, and as the embodiment of Assyria’s martial spirit, overshadow all other manifestations of divine power. This aspect of Ashur receives its most perfect expression during the reign of the four rulers—Sargon, Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, and Ashurbanapal—when Assyrian power reached its highest point. The success of the Assyrian armies, and consequent political aggrandisement served to increase the glory of Ashur, to whose protection and aid everything was ascribed—but it is Ashur the war-god, the warrior with bow and arrow within the solar circle, who gains in prestige thereby, while the spiritual phase of the deity as symbolised by the winged disc sinks into the background.

“For all this, culture and religion go hand in hand with political and material growth, and the Eu-phratean civilisation with its Assyrian upper layer reaches its zenith in the reign and achievements of Ashurbanapal. From the remains of his edifices with their pictorial embellishment of elaborate sculptures on the soft limestone slabs that lined the walls of palaces and temples, we can reconstruct the architecture and art of the entire historical period from the remote past to his own days; and through the contents of the library of clay tablets we can trace the unfolding of culture from the days of Sargon, Gudea, and Hammurabi, through the sway of the Kassites, and the later native dynasties down to the time when the leadership passes for ever into the hands of the cruder but more energetic and fearless Assyrians. The figure of Ashurbanapal rises before us as the heir of all the ages—the embodiment of the genius of the Babylonian-Assyrian civilisation, with its strength and its weaknesses, its spiritual force and its materialistic form.

Ashurbanapal and Scholarship

Morris Jastrow said: “The bulk, nay, practically, the whole of the literature of Babylonia was of a religious character, or touched religion and religious beliefs and customs at some point, in accord with the close bond between religion and culture which, we have seen, was so characteristic a feature of the Euphratean civilisation. The old centres of religion and culture, like Nippur, Sippar, Cuthah, Uruk, and Ur, had retained much of their importance, despite the centralising influence of the capital of the Babylonian empire. Hammurabi and his successors had endeavoured, as we have seen, to give to Marduk the attributes of the other great gods, Enlil, Anu, Ea, Shamash, Adad, and Sin, and, to emphasise it, had placed shrines to these gods and others in the great temples of Marduk, and of his close associate, Nebo, in Babylon, and in the neighbouring Borsippa. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

“Along with this policy went, also, a centralising tendency in the cult and, as a consequence, the rituals, omens, and incantations produced in the older centres were transferred to Babylon and combined with the indigenous features of the Marduk cult. Yet this process of gathering in one place the literary remains of the past had never been fully carried out. It was left for Ashurbanapal to harvest within his palace the silent witnesses to the glory of these older centres. While Babylon and Borsippa constituted the chief sources whence came the copies that he had prepared for the royal library, internal evidence shows that he also gathered the literary treasures of other centres, such as Sippar, Nippur, Uruk. The great bulk of the religious literature in Ashurbanapal’s library represents copies or editions of omen-series, incanta-tion-rituals, myths, legends, and collections of prayers, made for the temple-schools, where the candidates for the various branches of the priesthood received their training. Hence we find supplemental to the literature proper, the pedagogical apparatus of those days—lists of signs, grammatical exercises; analyses of texts, texts with commentaries, and commentaries on texts, specimen texts, and school extracts, and pupils’ exercises.

Multicultural Assyria

“The temple school appears to have been the depository in each centre of the religious texts that served a purely practical purpose, as handbooks and guides in the cult. Purely literary collections were not made in the south, not even in the temples of Babylon and Borsippa, in which the more comprehensive character of the religious texts was merely a consequence of the centralising tendency in the cult, and, therefore, likewise prompted by purely practical motives and needs. There are no temple libraries in any proper sense of the word, either in Babylonia or in Assyria. Ashurbanapal is the first genuine collector of the literature of the past, and it is significant that he places the library which he gathered, in his palace and not in a temple. Had there been temple libraries in the south, he would undoubtedly have placed the royal library in the chief temple of Ashur—as his homage to the patron deity of Assyria and the protector of her armies.

“At the same time, by transferring the literature of all the important religious centres of the south to his royal residence in Nineveh, Ashurbanapal clearly intended to give an unmistakable indication of his desire to make Nineveh the intellectual and religious as well as the political capital. His dream was not that of the Hebrew prophets who hoped for the day when from Zion would proceed the law and light for the entire world, when all nations would come to Jerusalem to pay homage to Jahweh, but his ambition partook somewhat of this character, limited only by his narrower religious horizon which shut him in.

Ashurbanapal hunting

Ashurbanipal Later Life, Lament and Deaths

According to National Geographic: Ashurbanipal assumed the throne when he was only 16 and ruled for 38 years. He presided over many campaigns from the Nile to the Persian Gulf. Most often he stayed in Nineveh, keeping watch over the empire’s administrative machinery and dealing with palace intrigues, while his generals conducted his wars. [Source: National Geographic, National Geographic,, August 25, 2022]

As Ashurbanipal ages, his writings change. On the last tablet known to be authored by him, he does not sound like the confident conqueror: "I did well unto god and man, to dead and living. Why have sickness ... and misery ... befallen me? I cannot do away with the strife in my country and the dissensions in my family. Disturbing scandals oppress me always. Misery of mind and of flesh bow me down; with cries of woe I bring my days to an end. On the day of the city-god, the day of the festival, I am wretched; death is seizing hold of me, and bears me down."

Historians don’t know what maladies afflicted him as he aged. Some hypothesize that lingering effects from a hunting wound caught up with him or perhaps an illness left him vulnerable at age 54. The aging king clearly saw the signs that his empire, his life’s work, was beginning to crumble. Perhaps Ashurbanipal foresaw that southern Babylon, Palestine, Phoenicia, and Media would be the first in his empire to go, and that short-lived rulers would fail to stem the tide of rebellion and departure.

How he died is unknown; even the year is uncertain. In Lord Byron’s play Sardanapalus (Greek for Ashurbanipal), the king sets his palace afire and perishes in the flames. That story is most likely legend since that is how Ashurbanipal’s brother Shamash-shum-ukin died when Ashurbanipal’s troops took over Babylon. Barely a decade after his death, the Assyrians would find themselves hemmed in their Mesopotamian homeland. Not long after, the great city of Nineveh itself would fall and be laid to waste. Two hundred years later, Xenophon would march his mercenary army where Nineveh once stood, but absolutely no trace of Ashurbanipal’s capital remained for his soldiers to trample underfoot.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024