Home | Category: First Modern Humans (400,000-20,000 Years Ago)

FIRST KNOWN MODERN HUMAN FOSSILS FOUND IN MOROCCO

Our concept of human origins was thrown for a major loop in 2017 with the announcement of the discovery of modern human fossils, dated to 315,000 years ago, about 100,000 years older than any other known remains of our species, Homo sapien, in an old mine on a desolate mountain in Jebel Irhoud, Morocco. Both the date of the fossils — skulls, limb bones and teeth from at least five individuals — and their location were surprises. “A blockbuster discovery,” one scientist said. [Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, June 8, 2017 ^]

Will Dunham of Reuters wrote: ““The Moroccan fossils, found in what was a cave setting, represented three adults, one adolescent and one child roughly age 8, thought to have lived a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. These were found alongside bones of animals including gazelles and zebras that they hunted, stone tools perhaps used as spearheads and knives, and evidence of extensive fire use. An analysis of stone flints heated up in the ancient fires let the scientists calculate the age of the adjacent human fossils, Max Planck Institute archaeologist Shannon McPherron said. ^

The fossils were found at Jebel Irhoud, a former barite mine 100 kilometers west of Marrakesh, where excavations had been going on for years. Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian: “Jebel Irhoud has thrown up puzzles for scientists since fossilised bones were first found at the site in the 1960s. Remains found in 1961 and 1962, and stone tools recovered with them, were attributed to Neanderthals and at first considered to be only 40,000 years old. [Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian, June 7, 2017 |=|]

Gemma Tarlach wrote in Discover: The overall picture one gets is of a hunting encampment, as they were moving across the area in search of subsistence,” McPherron added. And there is strong evidence the hominins were indeed on the move. The flint they were using for their tools is not local. Analysis showed it came from a site more than 20 kilometers away, suggesting the hominins intentionally sought out quality tool-making material and carried it with them. [Source: Gemma Tarlach, Discover, June 7, 2017]

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Modern Origins: A North African Perspective by Jean-Jacques Hublin (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Evolution of Hominin Diets: Integrating Approaches to the Study of Palaeolithic Subsistence” by Jean-Jacques Hublin, Michael P. Richards, Editors (2009) Amazon.com;

“Homo Sapiens Rediscovered: The Scientific Revolution Rewriting Our Origins” by Paul Pettitt Amazon.com;

“A Pocket History of Human Evolution: How We Became Sapiens”

by Silvana Condemi, Francois Savatier, et al. Amazon.com;

“Ancient Bones: Unearthing the Astonishing New Story of How We Became Human” by Madelaine Böhme, Rüdiger Braun, Florian Breier (2022) Amazon.com;

“Processes in Human Evolution: The journey from early hominins to Neanderthals and modern humans” by Francisco J. Ayala and Camilo J. Cela-Conde (2017) Amazon.com;

“Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” by Yuval Noah Harari (2011) Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth” by Chris Stringer (2013)

Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes” By Svante Pääbo (2014) Amazon.com;

“The World Before Us: How Science is Revealing a New Story of Our Human Origins”

By Tom Higham (2021) Amazon.com;

“Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art” by Rebecca Wragg Sykes (2020) Amazon.com;

Life in Prehistoric North Africa

Jebel Irhoud location

Megalithic structures like Stonehenge and the stone circles in Brittany have been found in Morocco as well as as far north as Sweden. It has been suggested that the people who built them shared similar beliefs. Amber, which originates from the Baltic region, more than a thousand kilometers away, has also found it way to North Africa and been used to make jewelry and ornaments.

According to Archaeology magazine: A hundred and fifty thousand years or so ago — ages before escargot became a delicacy — humans ate land snails on a regular basis. Evidence for this comes from tens of thousands of snail shells documented in Haua Fteah Cave in Libya. Some of the shells have holes indicative of drilling, which broke the suction that holds snails secure and made it possible to suck them out. Patterns in the deposits suggest that early humans turned to snails, which can be laborious to collect, during times when other sources of food were hard to come by. [Source: Samir S. Patel Archaeology magazine, January-February 2016]

Faunal remains from the Takarkori rock shelter in southwestern Libya underscore just how different the environment was there 10,000 years ago. While today the site is in the Sahara Desert, at the beginning of the Holocene period the area was dotted with lakes, ponds, and waterways. Humans used the shelter between 10,200 and 4,650 years ago. Their discarded food scraps around the site are giving experts insight into their diet. Of 18,000 bones thus far recovered, nearly 80 percent belong to fish species, mainly catfish and tilapia. [Source: Archaeology magazine, May-June 2020]

The plateau atop a sandstone outcrop called Messak Settafet in the central Sahara in Libya could be the earliest example of an entire landscape created and modified by humans. Archaeologists found an average of 75 lithics per square meter — a carpet of stone tools and man-made fragments spanning hundreds of thousands of years and perhaps thousands of square miles. The finds demonstrate just how important tool technologies were for early hominins, and that the area was likely a magnet for stone-hungry populations across the region. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2015]

Well-Preserved 90,000-Year-Old Human Footprints Found on a Moroccan Beach

In 2022, researchers happened upon some very well-preserved 90,000-year-old the footprint near the northern tip of North Africa while studying boulders at a nearby beach, according to a study published January 23, 2024 in the journal Scientific Reports. "Between tides, I said to my team that we should go north to explore another beach," study lead author Mouncef Sedrati, an associate professor of coastal dynamics and geomorphology at the University of Southern Brittany in France, told Live Science. "We were surprised to find the first print. At first, we weren't convinced it was a footprint, but then we found more of the trackway." [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, January 30, 2024]

Live Science reported: Analysis of the site, which is the only known human trackway site of its kind in North Africa and the Southern Mediterranean, revealed two trails containing a total of 85 human footprints stamped into the beach by a group of at least five early modern humans.

The team used optically stimulated luminescence dating, a technique that determines when specific minerals on or near an artifact were last exposed to heat or sunlight. Based on the age of the fine grains of quartz that make up the bulk of the gently sloped beach's sand, researchers determined that a multigenerational group of Homo sapiens walked on the beach roughly 90,000 years ago, creating the pathways. The event took place during the Late Pleistocene, also known as the last ice age, which ended around 11,700 years ago, according to the study.

"We took measurements on-site to determine the length and depth of the prints," Sedrati said. "Based on the foot pressure and size of the footprints, we were able to determine the approximate age of the individuals, which included children, adolescents and adults."

The researchers credit the excellent preservation of the ancient impressions to a number of factors, including the beach's layout and the long reach of the tides for "the final preservation of the footprints," according to the study. "The exceptional thing is the position of the beach on a rocky platform that is covered in clay sediments," Sedrati said. "These sediments create good conditions to preserve the tracks on the sandbar while the tides rapidly buried the beach. That's why the footprints are so well preserved here."

However, the researchers remain uncertain about what the ice age group was doing on the beach, and future analysis of the site could reveal that information. But they'll have to act quickly, as "the ongoing collapse of the rocky shore platform … could lead to its eventual demise," including of the tracks preserved on it, the team wrote in the study. "We hope to learn about the total history of this group of humans and what they were doing there," Sedrati said.

Jebel Irhoud tools: a through i are pointed forms, which are very common; j through k are the Levellois prepared core flakes

Tools from Jebel Irhoud Man

Gemma Tarlach wrote in Discover: “In addition to the hominin fossils, Jebel Irhoud is home to a number of stone tools, many made from non-local material which suggests a higher degree of intention than more primitive hominin tool-makers. “The thing that characterizes the Middle Stone Age from the time that came before is a shift from large, heavy-duty tools to an emphasis on producing lighter stone flakes that allowed increased efficiency in hunting. Along with an emphasis on pointed forms, there was an emphasis on quality materials,” McPherron explained, adding that the hominins’ apparent ease of using controlled fire also speaks to their fairly advanced cognitive abilities for the time.” [Source: Gemma Tarlach, Discover, June 7, 2017]

According to the Max Planck Institute: The fossils were found in deposits containing animal bones showing evidence of having been hunted, with the most frequent species being gazelle. The stone tools associated with these fossils belong to the Middle Stone Age. The Jebel Irhoud artefacts show the use of Levallois prepared core techniques (making stone tools by first striking flakes off the stone, or core, along the edges to create the prepared core and then striking the prepared core in such a way that the intended tool is flaked off with all of its edges pre-sharpened) and pointed forms are the most common. Most stone tools were made from high quality flint imported into the site. Handaxes, a tool commonly found in older sites, are not present at Jebel Irhoud. Middle Stone Age artefact assemblages such as the one recovered from Jebel Irhoud are found across Africa at this time and likely speak to an adaptation that allowed Homo sapiens to disperse across the continent. [Source: Max Planck Institute, June 7, 2017]

"The stone artefacts from Jebel Irhoud look very similar to ones from deposits of similar age in east Africa and in southern Africa" says Max Planck Institute archaeologist Shannon McPherron. "It is likely that the technological innovations of the Middle Stone Age in Africa are linked to the emergence of Homo sapiens." The new findings from Jebel Irhoud elucidate the evolution of Homo sapiens, and show that our species evolved much earlier than previously thought. The dispersal of Homo sapiens across all of Africa around 300 thousand years is the result of changes in both biology and behaviour.

World's Oldest Jewelry? — 150,000-Year-Old Shaped Shells from Morocco

In September 2021, researchers said in an article published by Science Advances they had discovered 33 shaped marine snail shells, dated as far back as 150,000 years. Ago, in a cave near Essaouira, about 400 kilometers southwest of Rabat, which they described as "the oldest ornaments ever discovered". According to the Robb Report: “The artifacts, which were discovered in the Bizmoune Cave near Morocco’s Atlantic coast between 2014 and 2018, have been through a series of rigorous tests to determine the age of shells and the surrounding sediment. Many of the beads are said to be between 142,000 and 150,000 years old. [Source: Rachel Cormack, Robb Report, November 25, 2021; AFP, September 24, 2021]

“Spanning roughly half an inch long, each bead was made from the shells of two different sea snail species. According to the excavation team, the holes in the center of each bead as well as the markings from wear and tear indicate that they were hung on strings or from clothing. Ancient beads from North Africa, such as these 33, are associated with the Aterian culture of the Middle Stone Age. These ancient settlers are widely considered to be the first to have worn what we now call jewelry.

Archaeologist Steven L. Kuhn and his team say the shell beads are the earliest known evidence of a widespread form of non-verbal human communication—that is, using jewelry to relay things about ourselves without the fuss of conversation “They were probably part of the way people expressed their identity with their clothing,” Kuhn said in a statement. “They’re the tip of the iceberg for that kind of human trait.” Kuhn, who also works as a professor of anthropology at the University of Arizona, believes the discovery shows that people used accessories to convey parts of their personality even hundreds of thousands of years ago. The beads, Kuhn said, are essentially a fossilized form of basic communication. The news comes shortly after a 23,000-year-old bead, which has been labeled the world’s oldest known piece of colored jewelry, was put on display in Japan.

world's oldest jewelry from Morocco

In 2007, archaeologists announced that they found tiny shells coated in red clay, dated to 82,000 years ago, in the Grotte des Pigeons at Taforalt in eastern Morocco. They were described as one the oldest known forms of human ornamentation. Kate Ravilious wrote in National Geographic: “Each shell has a hole pierced through it and a covering of red ochre, an ancient pigment made from clay. "The fact that they are colored and have deliberate perforations indicates that they were used as ornamentation," said Nick Barton from the University of Oxford in England, one of the archaeologists on the team. Some of the shell "beads" show signs of wear inside the perforation, indicating that they were strung together as necklaces or bracelets. "They were definitely meant to be seen," Barton said. [Source: Kate Ravilious, National Geographic, June 7, 2007 |]

See Separate Article: EARLY MODERN HUMAN CLOTHES, JEWELRY AND MAKE UP europe.factsanddetails.com

Oldest Bone Tools for Clothesmaking and Leatherworking — 120,000 Years Old — Found in Morocco

In September 2021, scientists reported in IScience that they had found the oldest bone tools for clothesmaking — 120,000 years old in Morocco. “"It's a major discovery because while older bone tools have been found elsewhere, it's the first time we have identified bone tools (this old) that were used to make clothing," Moroccan archaeologist Abdeljalil El Hajraoui said.[Source: AFP, September 24, 2021]

AFP reported: “The international team discovered more than 60 tools in Contrebandiers (Smugglers) Cave, less than 20 kilometres (12 miles) from the North African country's capital. They had been "intentionally shaped for specific tasks that included leather and fur working", the team wrote in a study published in the journal iScience. “The discovery could help answer questions on the origins of modern human behaviour, said El Hajraoui, a researcher at the National Institute of Archaeology and Cultural Heritage (INSAP). Sewing is a behaviour that has lasted" since prehistory, he told AFP. "Tools like those discovered in the cave were used for 30,000 years, which proves the emergence of collective memory."

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: While sorting through some 12,000 bone fragments excavated from Contrebandiers Cave near the Atlantic coast of Morocco, archaeologist Emily Hallett of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History noticed that some were smooth and shiny, as if they had been intentionally shaped by human hands. Upon consultation with colleagues, she determined that 62 of the fragments are bone tools dating to between 120,000 and 90,000 years ago. These include a number of tools made from animal rib bones of a type well known for its use in fur and leatherworking. “Once you have an animal skin, there are a lot of steps that have to be taken to process it so it’s supple, smooth, and ready to wear,” says Hallett. “These tools remove the connective tissues and fats from the skin without piercing and damaging it.” [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, January/February 2022

See Separate Article: EARLY MODERN HUMAN CLOTHES, JEWELRY AND MAKE UP europe.factsanddetails.com

Diet of Humans 15,000 Years Ago in Morocco

The cave of Taforalt in Morocco is one of the oldest and largest modern human sites in northern Africa. It was the home of Iberomaurusians, hunter-gatherers who date to the Late Pleistocene age, around 15,000 years ago — before the development of agriculture in the region. Teeth found in the cave indicate these people were were more gatherer than hunter. “Our study highlights the importance of the Taforalt population’s dietary reliance on plants, while animal resources were consumed in a lower proportion than at other Upper Palaeolithic sites with available isotopic data,” the study authors wrote. Taforalt cave is in northwestern Morocco, just south of the Alboran Sea. [Source: Irene Wright, Miami Herald, May 1, 2024]

Vegetation and water bodies in early Holocene (top), between about 12,000 and 7,000 years ago, and Eemian

In a study published on April 29, 2024 in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, an international team of researchers analyzed the isotopes in the prehistoric teeth from 15,000 years ago. “It has long been thought that meat played an important role in the diet of hunter-gatherers before the Neolithic transition,” according to an April 29 news release from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. “However, due to the scarcity of well-preserved human remains from Paleolithic sites, little information exists about the dietary habits of pre-agricultural human groups.”

Irene Wright wrote in the Miami Herald: Plants and animals are full of different elements like carbon, nitrogen, zinc and strontium, so when they are consumed, those elements go into the person eating them. Those elements build up over time, allowing researchers to measure their percentage and tell how much of a person’s diet was made up of plants versus animals, according to Frontiers for Young Minds. The ratio of nitrogen, for example, gets higher as you go up the food chain. A plant would have a low ratio, then an herbivore who eats lots of plants would have a higher ratio. A predator who eats lots of herbivores would have an even higher ratio of nitrogen. The study is the first of its kind to analyze zinc isotopes in the enamel of ancient teeth, according to the study, allowing for a more in-depth look at the prehistoric diets than ever before.

“The study’s major conclusions clearly show that the diet of these hunter-gatherers included a significant proportion of plants belonging to Mediterranean species, predating the advent of agriculture in the region by several millennia,” according to the release. “Archaeobotanical remains found at the site, such as acorns, pine nuts and wild pulses, further support this notion.” The researchers analyzed teeth from people of varying ages, including young children and infants who were buried in the cave. The young teeth also had similarly high concentrations of plant-based isotopes, suggesting “plant foods were also introduced into infant diets and may have served as weaning products for this human population,” according to the release.

Meat-Eating, Hunting and Being Hunted in Prehistoric Morocco

Irene Wright wrote in the Miami Herald: Human cultures during this era of history were thought to rely heavily on meat for sustenance because agriculture had not yet been established in North Africa, and hunting gave people more “bang for their buck,” meaning it provided lots of protein for less energy than gathering plants and nuts, according to the study. These findings suggest for the Iberomaurusian people this wasn’t the case, and they may have been beginning the shift to a lower reliance on meat, but the researchers aren’t completely sure why. [Source: Irene Wright, Miami Herald, May 1, 2024]

There is a chance that the availability of these animals decreased during winter months, according to the study, requiring people at the time to spend more energy collecting plants and nuts that could be stored through the winter. Sheep were a commonly hunted animal, according to the study, but there isn’t evidence that their population was in decline during this evolutionary period. There also may have just been a larger abundance of edible plants in their area, making the effort of collecting them worth the people’s time.

According to Archaeology magazine: Early humans certainly competed with large carnivores for resources, including prey and the natural shelter of caves, but there is little direct evidence for their interaction before the Upper Paleolithic (roughly 50,000 to 10,000 years ago), when humans began hunting carnivores in numbers. A hominin bone belonging to the species Homo rhodesiensis and around 500,000 years old, found among a large deposit of bones in a cave in Casablanca, had been cracked, gnawed, and punctured — probably by an extinct hyena. The find shows how easily humans and large carnivores could change places on the food chain. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2016]

Ten thousand years ago, the Sahara was a far greener place. As it became more arid, people came to rely heavily on livestock, and rock art from the region depicts cattle and even milking. But rock art is hard to date, making it difficult to identify the onset of dairy practices in Africa. New analysis of residues in pots has revealed evidence of milk fat that can be reliably dated to around 7,000 years ago. This early onset of dairy use might help unravel the evolution of the gene that lets many people digest lactose. [Source: Archaeology magazine, September-October 2012]

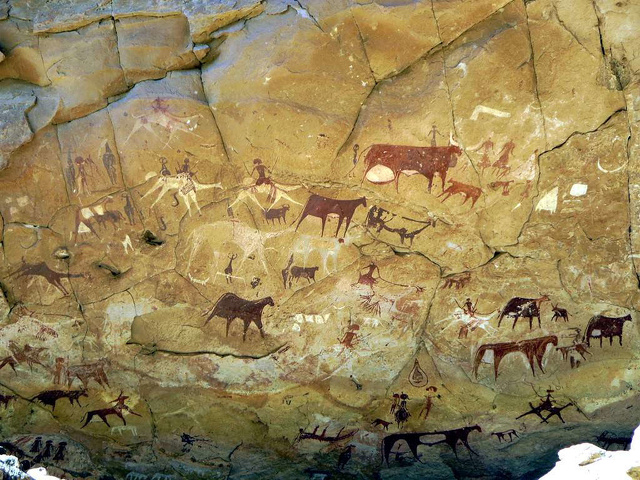

Saharan Rock Art

Extraordinary images of animals and people from time when the Sahara was greener and more like a savannah have been left behind. Engravings of hippos and crocodiles are offered as evidence of a wetter climate. [Source: David Coulson, National Geographic, June 1999; Henri Lhote, National Geographic, August 1987]

Most of the Saharan rock is found in Algeria, Libya, Morocco and Niger and to a lesser extent Egypt, Sudan, Tunisia and some of the Sahel countries. Particularly rich areas include the Air mountains in Niger, the Tassili-n-Ajjer plateau in southeastern Algeria, and the Fezzan region of southwest Libya. Some of the art found in the Sahara region is strikingly similar to rock art found in southern Africa. Scholars debate whether it has links to European prehistoric cave art or is independent of that.

The rock art of Sahara was largely unknown 1957 when French ethnologist Henri Lhote launched a major expedition to Tassili-n-Ajjer. He spent 12 months on the plateau with a team of painters, many of whom were hired by Lhote off the streets in Montmarte in Paris. The painters copied thousands of rock painting, in may cases tracing the outlines on paper and then filling them in with gouache. When the copies were displayed they created quite a stir, especially the images of figures that looked like space aliens. Lhote first visited the area in 1934, traveling from the oasis village of Djanet with a 30 camel caravan.

See Separate Article: SAHARAN ROCK ART factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Nature, phys.org and Natural History magazine

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery NewsNatural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024