Home | Category: First Modern Humans (400,000-20,000 Years Ago)

PREHISTORIC AFRICAN LIFE, TOOLS, HIGH-ALTITUDE HOMES AND DNA

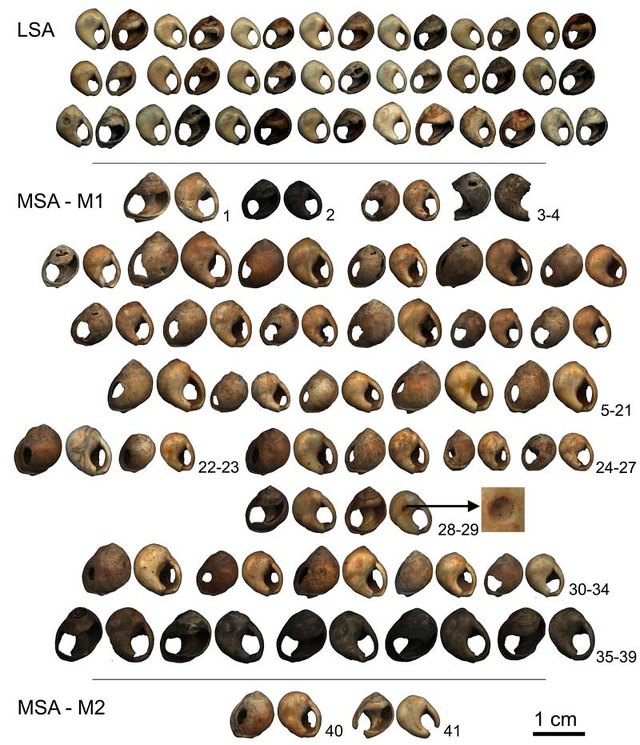

Charles Helm wrote in The Conversation:A substantial body of archaeological evidence has accumulated, indicating that ancient humans on the coast of South Africa adorned themselves with jewelry, developed sophisticated tool technology, created some of the world’s first engravings and drawings, and harvested shellfish, and seafood in a co-ordinated manner. In short, they exhibited many forms of modern human behavior — and the region has been described as a refugium in which our ancestors survived tough climatic conditions, and then thrived. [Source: Charles Helm, Research Associate, African Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience, Nelson Mandela University, The Conversation, November 9, 2020]

According to Archaeology magazine: Sidubu and Blombos are two landmark Middle Stone Age sites separated by more than 1,000 kilometers (600 miles). A detailed analysis of certain stone tools from both sites, published in 2015, reveals that the people at each used the same types of tools around 71,000 years ago, but that there are differences in how they were made. By a few thousand years later, little difference is seen in tool manufacture, suggesting that these groups shared a common tool technology, and then drifted apart and developed their own traditions, before returning to the same methods, perhaps due to increased cultural contact. [Source: Samir S. Patel Archaeology magazine, November-December 2015]

Given the harsh conditions, it’s notoriously difficult for humans to live at extreme altitudes. This did not deter some of our ancient ancestors. Evidence shows that humans were living at least 3,350 meters (11,000 feet) above sea level in the Bale Mountains in Ethiopia some 40,000 years ago. Hearths, stone tools, animal bones, and human feces from the Fincha Habera rock shelter comprise the earliest-known evidence of a high-altitude residential site. It is believed that humans survived there by eating giant mole rats and drinking water from glacial runoffs. [Source: Archaeology magazine, November-December 2019]

In 2017 scientists announced that geneticists had sequenced the first prehistoric African genome. The DNA comes from 4,500-year-old remains found in 2012 in a cave in the Ethiopian highlands. After comparing the genome with more than 100 populations from Africa, Europe, and Asia, scientists found, surprisingly, that it includes DNA from a potentially huge migration of farmers from the Middle East into Africa around 3,500 years ago — DNA that spread across the continent, even to groups in South Africa and Congo that had long been considered genetically isolated. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2017]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Homo Sapiens Rediscovered: The Scientific Revolution Rewriting Our Origins” by Paul Pettitt Amazon.com;

“A Pocket History of Human Evolution: How We Became Sapiens”

by Silvana Condemi, Francois Savatier, et al. Amazon.com;

“The First Human: The Race to Discover Our Earliest Ancestors” by Ann Gibbons (2006) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Bones: Unearthing the Astonishing New Story of How We Became Human” by Madelaine Böhme, Rüdiger Braun, Florian Breier (2022) Amazon.com;

“Processes in Human Evolution: The journey from early hominins to Neanderthals and modern humans” by Francisco J. Ayala and Camilo J. Cela-Conde (2017) Amazon.com;

“Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” by Yuval Noah Harari (2011) Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth” by Chris Stringer (2013)

Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes” By Svante Pääbo (2014) Amazon.com;

“The World Before Us: How Science is Revealing a New Story of Our Human Origins”

By Tom Higham (2021) Amazon.com;

“Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art” by Rebecca Wragg Sykes (2020) Amazon.com;

Africa During the Ice Ages and After

Dr Marta Mirazón Lahr from the University of Cambridge’s Leverhulme Centre for Human Evolutionary said: In the past there were periods of enormous rainfall in the tropics. When glaciers melted in the northern hemisphere, due to climate change, the water evaporated and then fell in the tropics as monsoon rains. The lakes were much higher and their margins were wider. We are using satellite images of the region to reconstruct where the ancient lake margins would have been when the lakes were last high, and that’s where we look.”[Source: University of Cambridge, May 13, 2013]

She and here colleague Professor Robert Foley carried out three field expeditions, in 2009, 2010 and 2011, to investigate their two chosen sites: the Turkana and the Nakuru-Naivasha basins of the Rift Valley in Kenya, and have made some spectacular finds on the ancient Turkana beaches. “Ten thousand years ago, this area was wetter, with gazelles, hippos and lions, and the beaches are still there even though the water is long gone. We’ve found shells on the surface, and harpoons the people used to fish with. We go there and we just walk,” said Mirazón Lahr. “A lot has already been exposed by the wind, and occasionally we find sites where things are buried, and then we dig.”

“We’re looking at the lithics — stone tools — and how these relate to times of particularly high lake levels,” said Mirazón Lahr. “Then we’re looking at the fauna and, if we’re lucky, we find actual human fossils. The oldest fossil ever found that looks like a modern human is 200,000 years old, and comes from the basin of Lake Turkana. We’re trying to find the fossils that mark the origin of Homo sapiens. The ancient Turkana beach is an incredibly fossil-rich site, and we’ve already found such exciting things!

“We have many human remains — about 700 fragments — mostly dating from between 12,000 and 7,000 years ago, which match the age of this beach. To do the population biology and answer the questions about diversity we need these large numbers. This is already the biggest collection of this age in Africa.”

How Geography and Climate Influenced the Development of Prehistoric Africans

Mirazón Lahr emphasises that geography and climate played a critical role in the origins and diversification of modern humans. “The times when the lakes were high were periods of plenty in East Africa,” she said. “When it was very wet there were lots of animals, the vegetation could grow, and you can imagine that the people would have thrived.” East Africa had a unique mosaic environment with lake basins, highlands and plains that provided alternative niches for foraging populations over this period. Mirazón Lahr believes that these complex conditions were shaped by varying local responses to global climate change. [Source: University of Cambridge, May 13, 2013]

“We think that early modern humans could live in the region throughout these long periods, even if they had to move between basins.” With a network of habitable zones, human populations survived by expanding, contracting and shifting ranges according to the changing conditions. By comparing the fossil records from different basins over time, Mirazón Lahr hopes to establish a spatial and temporal pattern of human occupation over the past 200,000 years.

Her approach is a multidisciplinary one, combining genetic, fossil, archaeological and palaeoclimatic information to form an accurate picture of events. Drawing on her wide-ranging interests from molecular genetics to lithics and prehistory, she believes that the way to find novel insights is to consider each problem from various angles.

This approach is intrinsic to the In Africa project, in which she and Foley are not just searching for new fossils, but also trying to build a complete picture of our early ancestors’ lives and the external forces that shaped their evolution, both biological and behavioural. “The project will be one of the first investigations into humans of this date in East Africa,” said Foley. “Given Africa is where we all come from, that’s critical.”

Vegetation and water bodies in early Holocene (top), between about 12,000 and 7,000 years ago, and Eemian

Modern Human Footprints in Africa

Footprints made 117,000 year ago at Langebaan Lagoon (about 60 miles north of Capetown, South Africa) appear to be made by a modern human.The prints were left on a sand dune during a driving rain storm. The sand dried out and was preserved under layers of sand. After it solidified into sandstone it was exposed by erosion and discovered by South African paleoanthropologist Lee Berger. The modern humans who made these prints are thought to have subsisted on shellfish, a rich, easy-to-collect source of protein. Some scientists have speculated that they spent a great amount of time in the water and the reason modern humans today have layers of fat like seals — in addition to sweat glands which are useful to creatures that live in out of water — is that the fat helped them stay warm during long periods of time spent in the water.

Since the report of 3.66 million-year-old footprints at the site of Laetoli in Tanzania in the 1980s, paleoanthropologists have found more than 100 walking trails preserved in rocks, ash and mud left by our hominin ancestors, which includes modern humans and extinct Homo species and closely-related ancestors. [Source: Kristina Killgrove, Live Science, May 30, 2023]

Engare Sero Footprints in Tanzania

According to Archaeology magazine: There are various places in Africa where ancient human footprints have been found, but none contain as many as the volcanic mudflat of Engare Sero, Tanzania where researchers have recently catalogued more than 400 dating to between 10,000 and 19,000 years ago. Two individuals appear to have been jogging, and there were two groups of mostly women and children traveling in different directions. It’s thought that even more footprints lie under nearby sand dunes. [Source: Samir S. Patel Archaeology magazine, January-February 2017]

The Engare Sero site was discovered in 2006 by Kongo Sakkae, a local Maasai tribesman. According to the Smithsonian: The 300 square meter site of Engare Sero, Tanzania, is the largest human fossil footprint site that has ever been discovered in Africa. It preserves over 400 human footprints in an ancient volcanic mudflow from nearby Oldoinyo L’engai, a still-active volcano in the East African Rift, which were hardened when the wet ash dried almost like concrete. The footprints are estimated to have been made between about 6,000 and 19,000 years ago and represent the distinct pathways of at least 20 different individuals. The Engare Sero research project team, led by Appalachian State University professor Cynthia Liutkus-Pierce and including Human Origins Program research scientist Briana Pobiner, has been excavating and analyzing the Engare Sero footprints since 2009. Their analysis suggests the footprints were made by a group of mostly adult females who were traveling together. When they looked at ethnographic literature, that kind of group structure is consistent with those observed during sexually divided foraging activities.

Related to a study published in Scientific Reports in May 2020, .Kevin Hatala, a paleoanthropologist at Chatham University in Pittsburgh, said: “Here we have a richly-detailed snapshot of a group that walked across this landscape at a very specific moment in human history. Based on our analysis of the sizes, spacings, and directions of the footprints, we believe they were made by a group of mostly adult females who were traveling together. Specifically, scientists believe the group was likely made up of 14 adult females, two adult males and one young male. [Source: Doyle Rice, USA TODAY, May 15, 2020]

Engare Sero Footprints

Appalachian State University professor Cynthia Liutkus-Pierce, a study co-author, said that the footprints have been remarkably preserved within an ancient volcanic mudflow produced by the nearby Oldoinyo L’engai, a still-active volcano in the East African Rift. “These prints were pressed into wet ash, which dries almost like concrete,” said Liutkus-Pierce. “The resilience of the hardened ash helps preserve the details of the footprints despite the natural erosion of the surrounding area over thousands of years,” she said.

“According to the study, the females who made the tracks were foraging together and were visited or accompanied by the males, as this behavior is seen today in modern hunter-gatherers such as the Ache and Hadza. The findings could indicate a division of labor based on sex in ancient human communities. "We suggest that these trackways may capture a unique snapshot of cooperative and sexually divided foraging behavior in Late Pleistocene humans," the authors wrote in the study.

153,000-Year-Old South African Tracks — Oldest Known Modern Human Footprints

In an article published April 25, 2023 in the journal Ichnos, archaeologists in South Africa announced they had discovered the footprints of modern humans dating to 153,000 years ago, the oldest known tracks attributed to our species, homo sapiens. Seven archaeological sites with tracks left by humans — called “ichnosites” — were discovered just east of the southern tip of the African continent, tens of miles inland from the ancient coast. The scientists used optically-stimulated luminescence (OSL) to figure out when the impressions were made.

Kristina Killgrove wrote in Live Science: These South African ichnosites included four with hominin tracks, one with knee impressions, and four with “ammoglyphs” — a term denoting any pattern, not just footprints, made by humans that has been preserved over time. Footprint evidence can add a great deal to the archaeological record, according to the researchers, as it "can provide not just an indication of humans travelling across these surfaces as individuals or groups, but also evidence of some of the activities that they engaged in," the authors wrote in the study. In South Africa, early evidence for modern human behavior includes personal adornment such as jewelry, development of intricate stone tools, the use of abstract symbols, harvesting of shellfish, and coastal cave and rock-shelter sites.

The researchers used OSL to date the South African track sites. This dating method works by estimating the time that has passed since grains of quartz or feldspar in or near the fossilized trackways were last exposed to sunlight. When surfaces that humans walked on were quickly buried, OSL can be used to figure out the date.

Samples from the Garden Route National Park (GRNP) track site, which contains seven identifiable tracks preserved in high cliffs, were dated to 153,000 years ago, plus or minus 10,000 years. Although there are older preserved footprints from other hominin species throughout Africa, Asia and Europe, the GRNP track site is now the oldest one made by Homo sapiens, which evolved in Africa around 300,000 years ago.

Most of the samples the team examined dated to between 70,000 and 130,000 years ago, and they were "pleasantly astonished" to find the 153,000-year-old track site, study first author Charles Helm, a research associate at the African Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience at Nelson Mandela University in South Africa, told Live Science. The discovery has "acted as a spur to continue our search for hominin tracks in deposits we know are even older," Helm said. The researchers note, however, that attribution of the tracks to a specific species is based more on archaeological artifacts and skeletal remains than on the shape of the tracks themselves. "Not all sites provide conclusive evidence," they wrote in their study, so "controversies and debate are likely to continue."

A photogrammetry image of some of the South African tracks; The horizontal and vertical scales are in meters

What the Footprints in South Africa Reveal

Charles Helm wrote in The Conversation: Around a hundred thousand years ago, South Africa’s Cape south coast was a busy place. Giraffes, crocodiles, hatchling sea turtles, and large bird species populated the landscape. Early humans were there, too. We know all of this because of fossil track sites that today dot the Cape south coast, which is about 400 kilometers east of Cape Town. These sites date to between 400,000 years and 35,000 years ago. The tracks were made on dunes and beaches, which became cemented over time. These ancient surfaces, which often preserve the tracks in remarkable detail. Our research team has been documenting these track sites since 2007. [Source: Charles Helm, Research Associate, African Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience, Nelson Mandela University, The Conversation, November 9, 2020]

Our team found its first hominin track site in 2016. We identified 40 tracks, estimated to be around 90,000 years old and indicating a party of humans traveling fast down a dune slope. The tracks were in a small cave west of what’s now the town of Knysna. Now we’ve found three further hominin track sites — and possibly a fourth. The sites are described in an article in the South African Journal of Science. One site, containing 32 tracks in a number of trackways, was unusual in that it we could examine both the surface on which the tracks were made (on a fallen slab near the high water mark) and, under an overhang in the cliffs above, the surface containing the infill layer. In fact, the tracks showed better preservation on the latter surface.

“These discoveries bring the total of southern African hominin track sites to six, following earlier discoveries at Nahoon Point in the Eastern Cape in 1965 and at Langebaan on the West Coast in 1995. Coincidentally, in the same week that our article was published, a site with tracks from approximately the same time period, and also attributed to Homo sapiens, was reported from the Arabian peninsula.

The three sites we have definitively identified lie within protected areas. One is within the Garden Route National Park, and two within the Goukamma Nature Reserve. Two of the sites described in our new research paper contained tracks of various sizes, suggesting the possibility of family groups. A third site contained three forefoot impressions with convincing evidence of toe impressions. Alongside these we found an array of nearly-parallel groove features and small circular depressions. These may have been made in the sand by a human using a finger or a stick.

“At the fourth site we found tracks of the right size and the right pace length to suggest a human trackmaker. But they were only visible in cross section in cliff layers. We felt it prudent not to over-interpret these features and make a definite conclusion, although they were highly suggestive and occurred close to our 2016 hominin tracksite.

Early Modern Humans at Blombos Cave in South Africa

There is some evidence that modern humans lived in Blombos, 185 miles from Capetown in South Africa, 80,000 to 95,000 years ago. The early humans who used Blombos Cave knew how to exploit their environment. Bones from hundreds of reef fish have been found. Since no fish hooks were discovered the scientists speculate that the fish may have been lured or directed into rock inlets and then speared. Many of the bones came from black musselcracker, a fish that still lives in waters near the cave.

Some of the world's earliest evidence of modern human art, jewelry, arrows and other things come from Blombos Cave (See links below). A team led by Christopher Henshilwood of the State University of New York and Judith Sealy of the University of Capetown have found interesting , well-preserved 70,000-year-old artifacts in Blombos Cave thought to have been produced by modern humans. The cave was used off and on by groups of modern humans for tens of thousands of years, then sealed shut for 70,000 years, only opening up again about 3,000 years ago, which explains why the objects found inside are so well preserved. [Source: Rick Gore, National Geographic, July 2000]

The artifacts include awls of a kind that doesn’t appear for another 40,000 years in Europe and objects thought to be spearheads that are serrated and crafted with skill that doesn't appear in Europe until 22,000 years ago. The points — made of a kind of quartzite found 10 to 20 miles from Blombos Cave — are so beautifully crafted Henshilood theorizes they may have had some symbolic or religious significance.

Finds in the cave, some scientists say, also hint to the first signs of human reasoning, cognition and art . The team found ocher that may have been used for drawing or body painting. Some pieces contained cross-hatched designs that may be indications of some kind of symbolic thinking. Scientists have speculated that some type of language with syntax must have been devised to communicate the ideas necessary to come up with these advancements.

According to Archaeology magazine: A lump of beeswax wrapped in plant material and tied with twine discovered in South Africa’s Border Cave in 2012 suggests that early hunter-gatherers may have been making a type of honey-based alcohol there as long as 40,000 years ago. The bundle also contained traces of a protein substance, possibly egg, and tree resin — a recipe lost to time. This possible progenitor of a type of mead that is still made by the nomadic San peoples of South Africa may have been among a variety of new foods and technologies produced during the Paleolithic period. [Source: Archaeology magazine, November-December 2020]

RELATED ARTICLES:

WORLD'S EARLIEST ART factsanddetails.com ;

HOW EARLY HUMANS MADE ART: METHODS, MATERIALS AND INTOXICATION europe.factsanddetails.com EARLY MODERN HUMAN CLOTHES, JEWELRY AND MAKE UP europe.factsanddetails.com ; EARLY MODERN HUMAN HUNTING: WITH BOWS, ARROWS AND ATLATLS factsanddetails.com

Border Cave in Northeast South Africa

Border Cave is an archaeological site located in the western Lebombo Mountains in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. The rock shelter has one of the longest archaeological records in southern Africa, which spans from the Middle Stone Age to the Iron Age.

A number of important discoveries have been made there. The site has been repeatedly excavated since Raymond Dart first worked there in 1934. Amongst earlier discoveries were the burial of a baby with a Conus seashell at 74,000 years ago, a variety of bone tools, an ancient counting device, ostrich eggshell beads, resin, and poison that may once have been used on hunting weapons.

In January 2020, scientists announced that they had found evidence of cooking, sharing and preparing starchy food at Border Cave at a time when early modern humans were just beginning to make their presence known in Africa. “The inhabitants of the Border Cave were cooking starchy plants 170,000 years ago,” Professor Lyn Wadley, a scientist from the Wits Evolutionary Studies Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa said. “This discovery is much older than earlier reports for cooking similar plants and it provides a fascinating insight into the behavioural practices of early modern humans in southern Africa. It also implies that they shared food and used wooden sticks to extract plants from the ground.”[Source: News Release, University of the Witwatersrand, January 2020]

How Early Humans Used Fire to Permanently Change the Landscape Around Lake Malawi

Humans have been living on the shores of Lake Malawi for tens of thousands of years. The three scientists listed below wrote in The Conversation: By combining data gathered by geochronologists who study the timing of landscape change and paleoenvironmental scientists who study ancient environments we have identified an instance in the very distant past of early humans bending environments to suit their needs. In doing so, they transformed the landscape around them in ways still visible today....So far we’ve recovered more than 45,000 stone artifacts here, buried many feet (1 to 7 meters) below the surface of the ground at sites that date to a time ranging from about 315,000 to 30,000 years ago. This was also a period in Africa when innovations in human behavior and creativity pop up frequently. [Source: David K. Wright, Professor of Archaeology, Conservation and History, University of Oslo, Jessica Thompson, Assistant Professor of Anthropology, Yale University, and Sarah Ivory, Assistant Professor of Geosciences, Penn State, The Conversation, May 15, 2023]

How did these artifacts get buried? Why are there so many of them? And what were these ancient hunter-gatherers doing as they made them? To answer these questions, we needed to figure out more about what was happening in this place during their time. For a clearer picture of the environments where these early humans lived, we turned to the fossil record preserved in layers of mud at the bottom of Lake Malawi. Over millennia, pollen blown into the water and tiny lake-dwelling organisms became trapped in layers of muck on the lake’s floor. Members of our collaborative team extracted a 1,250-foot (380-meter) drill core of mud from a modified barge, then painstakingly tallied the microscopic fossils it contained, layer by layer. They then used them to reconstruct ancient environments across the entire basin.

Today, this region is characterized by bushy, fire-tolerant open woodlands that do not develop a thick and enclosed canopy. Forests that do develop these canopies harbor the richest diversity in vegetation; this ecosystem is now restricted to patches that occur at higher elevations. But these forests once stretched all the way to the lakeshore. Based on the fossil plant evidence present at various times in the drill cores, we could see that the area around Lake Malawi repeatedly alternated between wet times of forest expansion and dry periods of forest contraction. As the area underwent cycles of aridity, driven by natural climate change, the lake shrank at times to only 5 percent of its present volume. When lake levels eventually rose each time, forests encroached on the shoreline. This happened time and time again over the last 636,000 years.

The mud in the core also contains a record of fire history, in the form of tiny fragments of charcoal. Those little flecks told us that around 85,000 years ago, something strange happened around Lake Malawi. Charcoal production spiked, erosion increased and, for the first time in more than half a million years, rainfall did not bring forest recovery.At the same time this charcoal burst appears in the drill core record, our sites began to show up in the archaeological record — eventually becoming so numerous that they formed one continuous landscape littered with stone tools. Another drill core immediately offshore showed that as site numbers increased, more and more charcoal was washing into the lake. Early humans had begun to make their first permanent mark on the landscape.

Fire use is a technology that stretches back at least a million years. Using it in such a transformative way is human innovation at its most powerful. Modern hunter-gatherers use fire to warm themselves, cook food and socialize, but many also deploy it as an engineering tool. Based on the wide-scale and permanent transformation of vegetation into more fire-tolerant woodlands, we infer that this was what these ancient hunter-gatherers were doing.

By converting the natural seasonal rhythm of wildfire into something more controlled, people can encourage specific areas of vegetation to grow at different stages. This so-called “pyrodiversity” establishes miniature habitat patches and diversifies opportunities for foraging, kind of like increasing product selection at a supermarket.

Just like today, changing any part of an ecosystem has consequences everywhere else. With the loss of closed forests in ancient Malawi, the vegetation became dominated by more open woodlands that are resilient to fire — but these did not contain the same species diversity. This combination of rainfall and reduced tree cover also increased opportunities for erosion, which spread sediments into a thick blanket known as an alluvial fan. It sealed away archaeological sites and created the landscape you can see here today.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except South African tracks by Charles Helm

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024