Home | Category: Pre-Islamic Arabian and Middle Eastern History / Pre-Islamic Arabia / Pre-Islamic Arabian and Middle Eastern History

WHAT DNA EVIDENCE SAYS ABOUT THE FIRST PEOPLE IN ARABIA

The Arabian Peninsula — which today includes Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates — has long been a key crossroads between Africa, Europe and Asia. The largest-ever study of Arab genomes, published in online on October 12, 2021 in the journal Nature Communications, revealed a number of interesting things about the earlist inhabitants of Arabia. [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, October 13, 2021]

Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science: Until recently the genetics of Arab populations was largely understudied. In the 2021 study, researchers conducted the first large-scale analysis of the genetics of a Middle Eastern population, examining DNA from 6,218 adults randomly recruited from Qatari health databases and comparing it with the DNA of people living in other areas of the world today and DNA from ancient humans who once lived in Africa, Europe and Asia. "This study is the first large-scale study on an Arab population," study co-senior author Younes Mokrab, head of the medical and population genomics lab at Sidra Medicine in Doha, Qatar, told Live Science.

The scientists found that DNA from Middle Eastern groups made significant genetic contributions to European, South Asian and even South American communities, likely due to the rise and spread of Islam across the world over the past 1,400 years, with people of Middle Eastern descent interbreeding with those populations, they said. "Arab ancestry is a key ancestral component in many modern populations," Mokrab said. "This means what would be discovered in this region would have direct implications to populations elsewhere."

Arrowheads found in Qatar in 1960 and ash from ancient campfires in Muscat found in 1983, both dated to around 6000 B.C., are the oldest examples of nomadic pastoralists living on the Arabian peninsula. Remains from Neolithic camps seems to indicate that the climate was wetter at that time and there was more food for grazing animals than today. Nomads are thought to have ranged between Iraq and Syria in the north a the Dhofar region of Oman in the south.

Shells and fishbone middens, dated to around 5000 B.C., found near Muscat is the earliest evidence of fishing communities along the Persian Gulf and Arabian Sea. Artifacts found at one of the middens (heaps of shells of marine life remains) included stone net sinkers, a necklace of shell, soapstone and limestone beads, finely-carved shell pendants. Graves contained human skeletons buried on beds of oyster shells or with sea turtle skulls. Analysis of the human remains turned up evidence of malaria and inbreeding. There was little evidence that they ate anything other than what they could take from the sea.

DNA Evidence Locates Most Ancient Middle Eastern Population

Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science: After comparing modern human genomes with ancient human DNA, the scientists discovered that a unique group of peninsular Arabs may be the most ancient of all modern Middle Eastern populations, Mokrab said. Members of this group may be the closest relatives of the earliest known farmers and hunter-gatherers to occupy the ancient Middle East, the researchers said. [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, October 13, 2021]

Ancestral Arab groups apparently underwent multiple splits 12,000 to 20,000 years ago, the scientists noted. This coincides with the way Arabia became drier, with some groups moving to more fertile areas, giving rise to settler communities, and others continuing to live in the arid region, which was more conducive to nomadic lifestyles, the researchers said.

The new study discovered high rates of inbreeding in some peninsular Arab groups dating back well into ancient times, likely resulting from the tribal nature of these cultures raising barriers to intermarriage outside tribal groups. Inbreeding can highlight rare mutations that may increase the risk of disease, so these new findings might help to reveal the causes of certain genetic disorders and lead to precision medicine to help diagnose and treat diseases in the communities represented in the study, the researchers said.

8,500-Year-Old Stone Houses Found in an U.A.E. Island

In May 2022, archaeologists announced they had discovered the oldest structure ever found in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) — the remains of a building that may be 8,500 years old.— on the island of Ghagha off Abu Dhabi. According to Live Science: An analysis of carbon isotopes, or versions of carbon, within charcoal fragments from the site show that the structure is 500 years older than any structures found before in the UAE, according to a February statement from the Department of Culture and Tourism - Abu Dhabi (DCT Abu Dhabi). Previously, the oldest structure found was on the island of Marawah. "These archaeological finds have shown that people were settling and building homes here 8,500 years ago," Mohamed Al Mubarak, the chairman of DCT Abu Dhabi, said in the statement.[Source: Emily Staniforth, Live Science, May 9, 2022]

The find highlights the historical connection between the people of the UAE and the sea. Before this discovery it was believed that people settled in the area which is now the UAE later in the Neolithic period as people expanded long-distance maritime trade routes, Al Mubarak said.

The structures found on Ghagha are believed to have been houses for a small community who lived on the island year-round. The rounded rooms have stone walls, the remains of which measure 3 feet (1 meter) high. Archaeologists also found artifacts, such as stone arrowheads, at the site. These would likely have been used for hunting, with the inhabitants of the island also relying on the sea for resources.

Archaeologists don't know exactly how long the settlement was inhabited, but the burial of a person at the site 5,000 years ago, after the settlement was abandoned, illustrates that the structure was an important cultural and historical aspect of the island. Burials from this period are a rare find on the Abu Dhabi islands, according to the statement. When Neolithic people lived on Ghagha and Marawah, these islands weren't "arid and inhospitable," but a "fertile coast," according to the statement. "This evidence recasts Abu Dhabi's islands within the cultural history of the broader region."

7,500-Year-Old Stone House in the U.A.E. and What Was Found Inside

A 7,500-year-old stone house found on Marawah Island in the mid 2010s was a three-room building. Hundreds of artifacts, as well as animal remains, suggest that the inhabitants herded sheep and goats, but also relied heavily on marine resources for trade and sustenance. The site, which appears to have been a house that later became a tomb (a single person was buried inside a partially collapsed room), comes from a time when the Gulf region was far wetter and greener than it is today. Other finds include stone tools, projectile points, and beads, as well as bones from both turtle and dugongs. [Source: Samir S. Patel Archaeology magazine, July-August 2016; Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2017]

The 7,500-year-old houses was found at a site at one of seven mounds on the island being excavated by the Abu Dhabi Tourism and Culture Authority (TCA) under archaeologist Abdulla Al Kaabi. Archaeologists predict that a complete Stone Age village could be unearthed. Dr Mark Beech, head of coastal heritage and palaeontology at TCA, said it was “very unusual” to find a Stone Age house “so well preserved that you have a complete plan of the structure”. “You can see the back yard and small walls projecting out, which is where the cooking was carried out, just like traditional Arabian houses. We knew it was a Stone Age site but did not expect it to be so well preserved.”[Source: By Al Nowais, March 27, 2017]

The walls of the home are up to 70 centimeters wide, which enabled the residents to have corbelled walls, meaning they could build a dome shape by placing the stones on top of each other. “There are seven major mounds and we picked the smallest to excavate, so they potentially may have more than one structure,” Dr Beech said.

TCA said that artefacts found on the island had helped archaeologists piece together what life was like for these villagers. They used stone tools to hunt and butcher animals, such as gazelle. Small beads made from shell and a small shark’s tooth were also found at the site and had been very carefully drilled, leading archaeologists to believe they were probably worn as adornments.

One of their most significant finds, during previous excavations, was a decorated ceramic jar from Iraq — the earliest evidence of sea trade during that period. “The recent excavations have clarified a lot of questions we had about this period,” Dr Beech said. “It tells us about life in the Stone Age and that people had domestic animals, but they also relied a lot on marine life. “It also shows that they had a varied diet and were involved in long-distance trade, as we see with the pottery. Life on these islands was actually quite good.“You had food resources, water supply and trade, and, of course, the climate was better than the present time.” Villagers lived in a completely different setting, with freshwater lakes and more vegetation.

7,000-Year-Old Tomb with Dozens of Skeletons Found in Oman

Pre-Islam Arab god Archaeologists have found the remains of dozens of people in a 7,000-year-old, half moon-shaped stone burial near Nafūn in Oman's central Al Wusta province. Located next to the coast in a stony desert, the tomb is among the oldest human-made structures ever found in Oman and nothing like it had been found in the region. "No Bronze Age or older graves are known in this region," Alžběta Danielisová, an archaeologist at the Czech Republic's Institute of Archaeology in Prague, told Live Science. "This one is completely unique." Danielisová is leading the excavations at the tomb. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, May 8, 2023]

Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: The tomb itself was discovered about 10 years ago in satellite photographs, and archaeologists think it dates to between 5000 B.C. and 4600 B.C. Skulls and bones from more than twenty bodies have been found in the tomb; archaeologists think they were deposited there at different times, after the bodies were left elsewhere to decompose.

A report on the project said the tomb's walls were made with rows of thin stone slabs, called ashlars, with two circular burial chambers inside divided into individual compartments. The entire tomb was covered with an ashlar roof, but it has partially collapsed, probably because of the annual monsoon rains. Several "bone clusters" were found in the burial chambers, indicating that the dead had been left to decompose before being deposited in the tomb; their skulls were placed near the outside wall, with their long bones pointed toward the center of the chamber. Similar remains were found in a smaller tomb next to the main tomb; archaeologists think it was built slightly later. Danielisová said there is evidence that the dead there were buried at different times, and three graves of people from the Samad culture, who lived thousands of years later, were found nearby.

The scientists are using dating techniques provided by the Nuclear Physics Institute of the CAS, the southern expedition leader Roman Garba, an archaeologist and physicist with the CAS, said in the statement. The same dating techniques will also be used to learn more about the roughly 2,000-year-old rows of stone "triliths" that have been found throughout Oman since the 19th century. Although the triliths are only a few feet (less than 1 meter) tall and were built during the Iron Age, some recent news reports compared them to England's Stonehenge.

The archaeologists are also investigating rock inscriptions near the tomb, although they were made thousands of years later, Danielisová said. Some of the symbols seem to be pictures, but others appear to be words and names. "We are still fuzzy about that," she said.

Mustalis — the Mysterious 7,000-Year-Old Stone Structures in Saudi Arabia

Over 1,600 huge, enigmatic rectangular complexes known as mustalis are scattered throughout the deserts of northwest Saudi Arabia. First observed in aerial surveys they date back to around 7,000 years ago. Mustali is the Arabic word for rectangle. Archaeology magazine reported: They are among the earliest known large-scale stone monuments found anywhere, predating even Egypt’s pyramids and Stonehenge. Scholars are unsure why they were constructed, but suggest they were used for religious ceremonies, since the remains of horned animals, especially cattle, are known to have been ritually deposited within them. [Source: Archaeology magazine, July 2021]

Live Science reported: While their appearance varies, they are usually rectangular in shape and often consisting of two platforms connected by two walls. Archaeological work indicates that some of the mustatils had a chamber in the center made of stone walls surrounding an open area with a standing stone in the center. The new research reinforces a theory proposed by other researchers that the mustatils had a ritualistic purpose and, in addition, provides evidence that they were part of a cattle cult. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, April 30, 2021]

"The mustatils of northwest Arabia represents the first large-scale, monumental ritual landscape anywhere in the world, predating Stonehenge by more than 2,500 years," Melissa Kennedy, assistant director of the Aerial Archaeology in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia project (AAKSA), said in a statement. "These structures can now be interpreted as ritual installations dating back to the late sixth millennium B.C., with recent excavations revealing the earliest evidence for [a] cattle cult in the Arabian Peninsula," a team of researchers wrote in a paper published April 30 in the journal Antiquity.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT ARABIA AND MIDEAST FROM THE AIR: MUSTALIS, DESERT KITES AND FUNERARY AVENUES factsanddetails.com

Desert Kites

Neolithic hunters used “desert kites” to herd, trap and then kill prey. Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Desert kites consist of pairs of rock walls that extend across the landscape, often over several miles, and converge on an enclosure where prey such as gazelles could be herded and then easily dispatched. Ones in Jordan date to the Neolithic period (12,000 to 7,000 years ago). Reuters reported: “Although such structures can also be found elsewhere in the arid landscapes of the Middle East and south west Asia, these are believed to be the oldest, best preserved and the largest, the experts said. [Source: Suleiman Al-Khalidi and Hams Rabah, Reuters, February 23, 2022; Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, January/February 2023]

Desert kites are dry stone wall structures found in mainly in Southwest Asia (Middle East) but also in North Africa, Central Asia and Arabia. They were first discovered from the air during the 1920s. There are over 6,000 known ones, ranging in size from less than a hundred meters to several kilometres. They typically have a kite shape formed by two convergent "antennae" that run towards an enclosure, all formed by walls of dry stone less than one metre high, but variations exist. Research published in 2022 has shown that pits several metres deep often lie at the margins of enclosures, which have been interpreted as traps and killing pits.[Source: Wikipedia]

Similar structures have been in northern areas, notably under Lake Huron, and were used during the glacial peak of the last Ice Age to hunt reindeer. Recently one was found in the Baltic Sea. They have also been found in Greenland. Dating kites is difficult;various dating methods like radiocarbon dating and optically stimulated luminescence have yielded a wide range of dates. There are a handful of description in old travel reports. Some kites have later archaeological structures bult over them so if that structure can be dated we know at least the desert kite is at least older than the structure, and calculating erosion rates can provide a better date.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT ARABIA AND MIDEAST FROM THE AIR: MUSTALIS, DESERT KITES AND FUNERARY AVENUES factsanddetails.com

Huge 4,000-Year-Old ‘Walled Oasis’ Found in the Arabian Desert

In 2024, scientists announced that satellite imagery had revealed a huge 4,000-year-old ‘walled oasis’ in the deserts of Khaybar in western Saudi Arabia. It is believed to be that a group of nomads constructed an “immense” network of defensive walls there and eventually settled as a community. according to a study published January 10 in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. [Source: Moira Ritter, Miami Herald, January 12, 2024]

The Miami Herald reported: Between 2020 and 2023, experts explored the Khaybar Oasis, an ancient agricultural center, the study said. Previously, satellite images had suggested the presence of a “walled oasis” in the area, but this is the first time “monumental defensive ‘belt’” was actually discovered. Researchers discovered 146 “large wall segments” belonging to the fortifications system — some only a few feet long, others extending hundreds of feet, according to the study.

The original wall was about 9 miles long, experts said. Today, about 41 percent of the structure, measuring approximately 3.7 miles, remains. Because the network has been interrupted by human and natural disruptions, it can be difficult to trace the original design of the fortifications. The fortifications construction indicates it was built in a single stage “with later additions or reconstructions,” researchers said. It would have taken an estimated 170,000 “working days,” and “a small local community would seem sufficient in terms of numbers to plan and raise the outer enclosure wall.”

Archaeologists dated the construction to between 2250 B.C. and 1950 B.C., and they estimate that it was used for at least four centuries, until between about 1626 B.C. and 1542 B.C. The fortification network served not only as a protection against raiders and invaders, but it also protected the settlement inside from nature and demarcated control while setting territory boundaries, researchers said.

Rajajel Columns and Other Arabian Stonehenges

The Rajajel Columns is an archaeological site of pillars carved from sandstone thought to be 6,000 years old. It is located in the Al Jawf Region in Saudi Arabia — in the suburb of Qara south of Sakakah. Some of the erected stone columns called Rajajil (“the men”) are higher than three meters, while they are about 60 centimeters thick. Described as Saudi Arabia’s Stonehenge’s, the site may belong to a temple built in the fourth millennium B.C.. .Many of the stone pillars have already fallen, while others lean at random angles. [Source: Wikipedia]

Paul Jongko wrote in Listverse,“The makers of these structures organized them in 54 groups, with each group having two to 19 stone pillars. At first glance, the stone monuments do not seem to resemble any meaningful pattern. However, if viewed from above, the stone pillars “suggest a rough alignment to sunrise and sunset.” [Source: Paul Jongko, Listverse, June 24, 2016]

“Archaeologists do not know much about Al-Rajajil. Questions, such as who built them and what their purpose is, remain unanswered. Though not much is known about these mysterious structures, experts have suggested that they don’t fulfill any religious purpose. This assumption was widely accepted after no human remains or religious artifacts and offerings were discovered in the vicinity of the stone pillars. If not for religious functions, then what might have been the use of Al-Rajajil? Experts suspect that whoever erected these stone monuments used them either for astronomical or political reasons. Aside from that, there’s also a group of researchers who suggest that they might have been used as a landmark. Al-Jouf, where the monuments are found, was an important stopover on the Yemen-Iraq trade route.

In an April 14, 2023 news release from the Czech Academy of Sciences, scientists announced that had found ancient tools, ostrich eggshell, Neolithic tombs and a mysterious monument dubbed “Arabian Stonehenge” at sites in the Dhofar Governorate in the southern part of Oman near border with Yemen. [Source: Brendan Rascius, Miami Herald, April 26, 2023]

Brendan Rascius wrote in the Miami Herald Perhaps the most puzzling discovery made at the Dhofar site was a 2,000-year-old monument that has been called Arabian Stonehenge due to similarities it shares with England’s well-known cluster of standing stones. Researchers refer to the stones as ritual monuments, or triliths. It’s not known who built them or what their purpose was. Triliths are made up of three flat standing stones that form a pyramid and are situated in groups, according to a study published in 2019 in the Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. More than 500 trilith sites with various configurations have been found on the Arabian peninsula, revealing “trails of mobility across southern Arabia,” according to the study. Researchers said that radiocarbon dating can be used to provide more information about the newly found monuments.

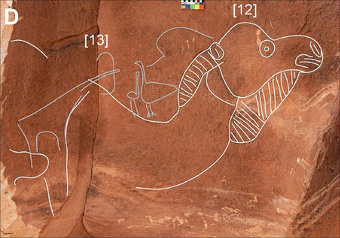

The second excavation site was in the Duqm province in central Oman and a Neolithic tomb was the major discovery made there. A megalithic structure concealing two circular burial chambers revealed the skeletal remains of at least several dozen individuals,” Alžběta Danielisová, one of the archaeologists, saids in the release. Also found were rock engravings dating between 5,000 B.C. and 1,000 A.D. that provide an illustrative record of human habitation of the area.

Marine Mollusks — An Ancient Arabian Food Source

Millions of shells of the marine mollusc Conomurex fasciatus have been found on the Farasan Islands in Saudi Arabia according to a study that examined fossil reefs near to the now-submerged Red Sea shorelines along presumed prehistoric migratory routes from Africa to Arabia. According to York University: The research team, led by the University of York, focused on the remains of 15,000 shells dating back 5,000 years to an arid period in the region. With the coastline of original migratory routes submerged by sea-level rise after the last Ice Age, the shells came from the nearby Farasan Islands in Saudi Arabia. [Source: York University, Ancientfoods, July 9, 2020]

The researchers found that populations of marine mollusks were plentiful enough to allow continuous harvests without any major ecological impacts and their availability would have enabled people to live through times of drought. Lead author, Dr Niklas Hausmann, Associate Researcher at the Department of Archaeology at the University of York, said: “The availability of food resources plays an important role in understanding the feasibility of past human migrations — hunter-gatherer migrations would have required local food sources and periods of aridity could therefore have restricted these movements. “Our study suggests that Red Sea shorelines had the resources necessary to provide a passage for prehistoric people.”

The study also confirms that communities settled on the shorelines of the Red Sea could have relied on shellfish as a sustainable food resource all year round. Dr Hausmann added: “Our data shows that at a time when many other resources on land were scarce, people could rely on their locally available shellfish. Previous studies have shown that people of the southern Red Sea ate shellfish year-round and over periods of thousands of years. We now also know that this resource was not depleted by them, but shellfish continued to maintain a healthy population.”

The shellfish species found in the archaeological sites on the Farasan Islands were also found in abundance in fossil reefs dating to over 100 thousand years ago, indicating that these shellfish have been an available resource over longer periods than archaeological sites previously suggested. Co-author of the study, Matthew Meredith-Williams, from La Trobe University, said: “We know that modelling past climates to learn about food resources is extremely helpful, but we need to differentiate between what is happening on land and what is happening in the water. In our study we show that marine foods were abundant and resilient and being gathered by people when they couldn’t rely on terrestrial food.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024