Home | Category: Early Mesopotamia, the Fertile Crescent and Archaeology / Pre-Islamic Arabian and Middle Eastern History

EARLIEST EVIDENCE OF MODERN HUMANS IN THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA

Qafzeh skull from Israel

Our concept of human origins was thrown for a major loop in 2017 with the announcement of the discovery of modern human fossils, dated to 300,00 years ago, about 100,000 years older than any other known remains of our species, Homo sapien, in an old mine on a desolate mountain in Morocco. Both the date of the fossils — skulls, limb bones and teeth from at least five individuals — and their location were surprises — “a blockbuster discovery.” [Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, June 8, 2017 ^]

Will Dunham of Reuters wrote: “The antiquity of the fossils was startling - a “big wow,” as one of the researchers called it. But their discovery in North Africa, not East or even sub-Saharan Africa, also defied expectations. And the skulls, with faces and teeth matching people today but with archaic and elongated braincases, showed our brain needed more time to evolve its current form. “This material represents the very root of our species,” said paleoanthropologist Jean-Jacques Hublin of Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, who helped lead the research published in the journal Nature.

Country — Date — Place — Notes

United Arab Emirates — 125,000 years before present — Jebel Faya — Stone tools made by anatomically modern humans

Oman — 75,000–125,000 years before present — Aybut — Tools found in the Dhofar Governorate correspond with African objects from the so-called 'Nubian Complex', dating from 75-125,000 years ago. According to archaeologist Jeffrey I. Rose, human settlements spread east from Africa across the Arabian Peninsula. [Source: Wikipedia]

Elsewhere in the Middle East and North Africa: Country — Date — Place — Notes

Morocco — 379,000–254,000 years before present — Jebel Irhoud — Anatomically modern human remains of eight individuals dated 300,000 years old, making them the oldest known remains categorized as "modern".

Israel — 195,000 –177,000 years before present — Misliya Cave, Mount Carmel — Fossil maxilla is y older than remains found at Skhyul and Qafzeh, two other very old sites in Israrel. Layers dating from between 250,000 and 140,000 years ago in the same cave contained tools of the Levallois type which could put the date of the first migration even earlier if the tools can be associated with the modern human jawbone finds.

Libya — 50,000–180,000 years before present — Haua Fteah — Fragments of 2 mandibles discovered in 1953

A 300,000-year-old tool site has been found at Dawadimi, about 300 kilometers west of Riyadh. At that time Arabia was considerably greener and wetter than it is now and supported elephants, giraffes and rhinoceros. The archaeologists from the Institute of Archaeology of the CAS in Prague unearthed a stone hand-ax in the Dhofar region of southern Oman which may date from the first migrations of early humans out of Africa between 300,000 and 1.3 million years ago.

See Separate Articles: SOUTHERN ROUTE OF OUT OF AFRICA THEORY factsanddetails.com ; OUT OF AFRICA AND THEORIES ABOUT EARLY MODERN HUMAN MIGRATIONS factsanddetails.com ; MIGRATIONS OF EARLY MODERN HUMANS factsanddetails.com ; NORTHERN ROUTE OF OUT OF AFRICA THEORY factsanddetails.com ; EARLY MODERN HUMANS MIGRATE TO ASIA factsanddetails.com ; EARLY MODERN HUMANS MIGRATE TO AUSTRALIA factsanddetails.com ; FIRST MODERN HUMANS MIGRATE TO EUROPE factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“An Introduction to Human Prehistory in Arabia: The Lost World of the Southern Crescent” by Jeffrey I. Rose (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Evolution of Human Populations in Arabia: Paleoenvironments, Prehistory and Genetics” by Michael D. Petraglia, Jeffrey I. Rose (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Middle and Upper Paleolithic Archeology of the Levant and Beyond by Yoshihiro Nishiaki, Takeru Akazawa, Editors Amazon.com;

” Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East: A Guide” by John J. Shea Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia Before History” by Petr Charvát Amazon.com;

“More than Meets the Eye: Studies on Upper Palaeolithic Diversity in the Near East”

by A. Nigel Goring-Morris, Anna Belfer-Cohen (2017) Amazon.com;

“Transitions Before the Transition: Evolution and Stability in the Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age” by Erella Hovers, Steven Kuhn (2006) Amazon.com;

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“Out of Africa I: The First Hominin Colonization of Eurasia” by John G Fleagle, John J. Shea, Editors (2010), Amazon.com;

“The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey” (Princeton Science Library) by Spencer Wells (2017) Amazon.com;

“Past Human Migrations In East Asia by Alicia Sanchez-Mazas” Amazon.com;

“Homo Sapiens Rediscovered: The Scientific Revolution Rewriting Our Origins” by Paul Pettitt Amazon.com;

“The Real Eve: Modern Man's Journey Out of Africa” by Stephen Oppenheimer (2004) Amazon.com;

“Asian Paleoanthropology: From Africa to China and Beyond” (Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology) by Christopher J. Norton and David R. Braun Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

First Humans Migrate from Africa to Asia via the the Middle East

The fact that some of earliest evidence of modern humans outside of Africa s in Australia suggests that the early man followed a coastal route through the Middle East, South Asia and Southeast Asia to Australia. It is believed that the migration was not a caravan-like journey but rather one in which some huts were set up on the beach and the migrants lived there for a while moving and then moved to a new location further to the east every couple of years. Traces of such a migration if it took place were covered in water and sediments when sea levels rose at the end of the Ice Age.

Some genetic evidence indicates that a group of 4,000 modern humans left Africa between 75,000 and 50,000 years ago and ultimately populated Asia. All non-Africans share genetic markers (the M168 marker in particular) carried by these early immigrants. The descendants of these people replaced all earlier types of humans, notably Neanderthals. All-non Africans are descendants of these people. The Onge from the Andaman Islands in India carry some of the oldest genetic markers found outside Africa.

Many scientists believe the migration took place rather late and humans that took part in it spread very far, very quickly, This theory is backed in part by the features of skulls of ancient modern men found in Europe, Asia and even Australia with those of the Hofmeyr skull found in South Africa in the 1950s and dated to be 33,000 to 42,000 years old. This finding was reported in a January 2007 article in the journal Science by team led by Frederick Grine at State University of New York at Stony Brook.

Early Modern Human Migration Route to Asia

Jebel Irhoud skull

The route of the early migrants that populated the world is still a matter of speculation. They may have migrated out of Africa via the Red Sea and the Nile Valley to the Middle East or across the southern Red Sea, making their way across southern Arabia to the Persian Gulf. At that time an ice age narrowed the gap across the Res Sea between the Horn of Africa and Arabia to only a few kilometers. It was originally that these early migrants made their way eastward via the Sinai peninsula but many think they crossed the Bab el Mandeb Strait, separating Djibouti from the Arabian Peninsula.. The straits across the Persian Gulf between Arabia and west Asia was also shortened by the ice age.

The migrants seem to have stayed near the sea during much of the migration. That way they had acess to reliable sources of food in the form of fish and mollusks. Who knows they may have even used boats to follow the coast — a method many scientists theorize was used tens of thousands of years later to reach America. To reach Australia within the timeline of theory would have required an advance of about on kilometer a year.

The archaeological record indicates the migrants made it as far as India around 75,000 years ago. Tools found Jwalapuram, a 74,000-year-old site in southern India, match those used in Africa from the same period. Excavated by anthropologist Michael Petraglia of the University of Cambridge, the site until recently was the oldest known outside of Africa aside from Qafzeh and Skhul in Israel.

Some scientists feel the migration out of Africa was also accompanied by revolutions in behavior and technology such as more developed social networks and advanced tools and sophisticated language that gave them ability to prosper in new lands and in some cases drive out hominids that already lived there.

Southern Route Out of Africa

Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal of University College London wrote: “In contrast, mtDNA studies have traditionally favored a Southern route across the Bab el Mandeb strait at the mouth of the Red Sea. From there, modern humans are thought to have spread rapidly into regions of Southeast Asia and Oceania. For example, two studies have concluded that individuals assigned to haplogroup L3 migrated out of the continent via the Horn of Africa. Furthermore, Fernandes et al. analyzed three minor West-Eurasian haplogroups and found a relic distribution of these minor haplogroups suggestive of ancestry within the Arabian cradle, as expected under a Southern route. That being said, many mtDNA studies, including these, are based on the premise that haplogroup L3 represents a remnant Eastern African haplogroup. Groucutt et al have recently theorized that L3 does not provide conclusive evidence for a shared African ancestor, given human demographic history is likely to be less “tree-like” than has been consistently assumed by mtDNA analyses. As an example, they showed that L3 could have arisen inside or outside of Africa if gene flow occurred between the ancestors of Africans and non-Africans following their initial divergence. [Source: Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal of University College London, “Human Dispersal Out of Africa: A Lasting Debate,” Evolutionary Bioinformatics, April 21, 2016 ~]

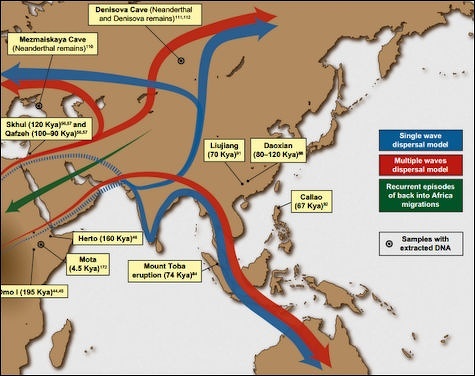

single and multiple migration waves into Asia

“Short Tandem Repeats (STR) and analysis of LD decay in combination with geographic data have also been used to support a Southern route via a single wave serial bottleneck model. Under this model, it is thought that a group crossed the mouth of the Red Sea and traveled along the Southern coast of the Arabian Peninsula toward India as “beachcombers,” exploiting shellfish and other marine products. Migrations then continued in an iterative wave as populations dispersed and expanded into uninhabited areas. This is consistent with a glacial maximum occurring during this time period, which caused sea levels to fall allowing potential passage across the mouth of the Red Sea. ~

“From an archeological perspective, evidence indicative of maritime exploitation is extremely limited. The discovery of artifacts from the Abdur Reef Limestone in the Red Sea and archeological sites in the Gulf Basin that indicate long-standing human occupation earlier than 100, 000 years ago may offer some evidence; however, whether these represent the activities of the ancestors of modern-day human groups is still an open question. Furthermore, Boivin et al caution that while coastal regions may have been important, a coastal-focused dispersal would still have been problematic and not necessarily conducive to rapid out of Africa dispersal.” ~

See Separate Articles: SOUTHERN ROUTE OF OUT OF AFRICA THEORY africame.factsanddetails.com ; OUT OF AFRICA AND THEORIES ABOUT EARLY MODERN HUMAN MIGRATIONS factsanddetails.com ; MIGRATIONS OF EARLY MODERN HUMANS factsanddetails.com ; EARLY MODERN HUMANS MIGRATE TO ASIA factsanddetails.com ; EARLY MODERN HUMANS MIGRATE TO AUSTRALIA factsanddetails.com

Prehistoric Green Arabia Attracted Early Humans from Africa

Parts of the Arabian Peninsula that are now covered by deserts and dunes were once home to forests, savannahs and lakes teeming with large animals such as hippopotamuses. According to Associated Press: “Extensive excavations over a decade revealed stone tools from multiple periods of prehistoric settlement by early human groups, the oldest 400,000 years ago. Analysis of sediment samples from the ancient lakes and remains from hippos and other animals revealed that during several periods in the distant past, the peninsula hosted year-round lakes and grasslands according to a study published in Nature in September 2021. [Source: Christina Larson, Associated Press, September 2, 2021]

During these windows of hospitable climate, early humans and animals moved from northeast Africa into the Arabian Peninsula, the researchers say. ““Flowing rivers and lakes, surrounded by grasslands and savannah, would have attracted animals and then the early humans that were in pursuit of them,” said Petraglia. Hippos require year-round water bodies several yards (meters) deep to live. Remains of other animals, including ostriches and antelopes, indicate “a strong biological connection to northeast Africa,” he said.

“Until a decade ago, the Arabian Peninsula was a blank spot on the map for scientists trying to reconstruct the story of early human evolution and movements out of Africa. Much more is known about early human settlements in the Levant region — modern-day Israel, Jordan, Lebanon and parts of Syria — where extensive archaeological research has been carried out for more than a century. “Arabia has not been part of the story of early human migration because so little work was done there before,” said co-author Michael Petraglia, a paleolithic archaeologist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany. The research team included scientists from Germany, Saudi Arabia, Australia, the United Kingdom and elsewhere. [Source: Christina Larson, Associated Press, September 2, 2021]

“The impetus to look closely for archeological remains in the region came from satellite imagery that revealed traces of prehistoric lakes in now-arid regions. “We noticed color patterns made by ancient lakes — sand dunes are kind of orange-colored, while ancient lakes are tinted white or gray,” said Groucutt, who is also based at the Max Planck Institute.

““What this research group has done is really exquisitely combine archaeology and climate records going back 400,000 years to show that early humans moved across this landscape when the climate changed,” said paleoanthropologist Rick Potts, who directs the Human Origins Program at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. The episodic presence and absence of populations in the Arabian Peninsula was in tune with climate oscillations,” said Potts, who was not involved in the new study.

120,000-Year-Old Jebel Faya in the U.A.E

Stone tools from the Jebel Faya site in the United Arab Emirates, dated to 120,000 years ago, suggest that modern humans migrated out Africa much earlier than thought. Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian: ““A team led by Hans-Peter Uerpmann at the University of Tübingen in Germany uncovered the latest stone tools while excavating sediments at the base of a collapsed overhang set in a limestone mountain called Jebel Faya, about 35 miles (55km) from the Persian Gulf coast. Previous excavations at the site have found artefacts from the iron, bronze and neolithic periods, evidence that the rocky formation has provided millennia of natural shelter for humans. The array of tools include small hand axes and two-sided blades that are remarkably similar to those fashioned by early humans in east Africa. The researchers tentatively ruled out the possibility of other hominins having made the tools, such as the Neanderthals that already occupied Europe and north Asia, as they were not in Arabia at the time. “The stones, a form of silica-rich rock called chert, were dated by Simon Armitage, a researcher at Royal Holloway, University of London, using a technique that measured how long sand grains around the artefacts had been buried. [Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian January 27, 2011 |=|]

Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Jebel Faya is a collapsed rock shelter that contains evidence of several distinct periods of occupation from roughly 125,000 years ago to 34,000 years ago. The site lies at the base of a mountain, near the mouth of a valley and a now-dry lake basin. A key piece of evidence about a possible early Homo sapiens occupation comes via the stone tools from the shelter's oldest layers, which are dated to between 125,000 and 90,000 years ago. According to Anthony Marks of Southern Methodist University, these tools, notably, were made using techniques similar to those being practiced in eastern Africa by Homo sapiens at that time. They are also markedly different from tools made by both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals living farther north in the Levant and in Iran's Zagros mountains. Marks believes that this shows that the earliest people to settle Jebel Faya came from eastern Africa, without passing through the Sinai farther north, and supports the idea of an early southern migration. [Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2011]

“Although fewer than a dozen stone tools from the site's earliest occupants were found, they show that the people there were making tools using a bifacial flaking technique, meaning that flakes were struck from both the top and bottom faces of a stone to make a blade. "Earlier than 200,000 years ago, there is not a sign of any [tools being made using] bifacial reduction in the Levant or in the Zagros anywhere," says Marks. "On the other hand, in East Africa and Northeast Africa, bifacial reduction is a constant part of the people's technical repertoire." At Jebel Faya they also made a stone tool called a "foliate," which is shaped like a leaf and it, too, is similar to a type of tool made in Northeast Africa, but not in areas north of the site. One challenge in determining who occupied the site is that no bones of any hominin species from this time period have been found there. However, according to project director Hans-Peter Uerpmann of the University of Tübingen, and Marks, bones of Homo sapiens have been found with comparable stone tools in Northeast Africa. In addition, Jebel Faya is located far south of the areas where Neanderthals were living at this time. The conclusion is that anatomically modern humans were the earliest occupants of Jebel Faya. And due to the absence at the site, after 90,000 years ago, of the kinds of stone tools that they made, it is believed that they left. According to the archaeological findings, later residents of the site appear to have migrated there from the north. A collection of stone tools believed to date between 90,000 and 40,000 years ago seem to have been derived directly from the tool-making traditions of people who lived in the Levant or the Zagros mountains.

100,000-Year-Old Modern Human Fossil in the United Arab Emirates

In January 2011, a team led Simon Armitage from Royal Holloway, University of London announced in the journal Science that had found an early modern human “toolkit” on the Arabia peninsula that was at least 100,000 years old. Discovered at the archaeological site in the United Arab Emirates, the toolkit includes relatively primitive hand-axes along with a variety of scrapers and perforators — tools that resemble tools used by early humans in east Africa but not display the craftsmanship that emerged later from the Middle East. The age of the stone tools was calculated using a technique known as luminescence dating and determined to be about 100,000 to 125,000 years old. [Source: ScienceDaily; Science, January 28, 2011]

Scientists say: 1) the dates imply that modern humans first left Africa much earlier than researchers had expected; 2) the contents of the toolkit imply that technological innovation was not necessary for early humans to migrate onto the Arabian Peninsula; and 3) the location of the find implies early modern humans migrated eastward directly from Africa rather than via the Nile Valley or the Near East. [Ibid]

Researchers led by Hans-Peter Uerpmann from Eberhard Karls University in Tübingen, Germany analyzed sea-level and climate-change records for the region during the last interglacial period, approximately 130,000 years ago. They determined that the Bab al-Mandab Strait, which separates Arabia from the Horn of Africa, would have narrowed due to lower sea-levels, allowing safe passage prior to and at the beginning of that last interglacial period. At that time, the Arabian Peninsula was much wetter than today with greater vegetation cover and a network of lakes and rivers. Such a landscape would have allowed early humans access into Arabia and then into the Fertile Crescent and India, according to the researchers. [Ibid]

120,000-Year-Old Human Footprints Found in Inland Arabia

In 2020, scientists announced they had found 120,000-year-old human footprints found in an inland area of Saudi Arabia. Ann Gibbons wrote in Science: One day about 120,000 years ago, a few humans wandered along the shore of an ancient lake in what is now the Nefud Desert in Saudi Arabia. They may have paused for a drink of fresh water or to track herds of elephants, wild asses, and camels that were trampling the mudflats. Within hours of passing through, the humans' and animals' footprints dried out and eventually fossilized. Now, these ancient footsteps offer rare evidence of when and where early humans once inhabited the Arabian Peninsula. "These are the first genuine human footprints of Arabia," says archaeologist and team leader Michael Petraglia of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. [Source: Ann Gibbons, Science, September 17 2020]

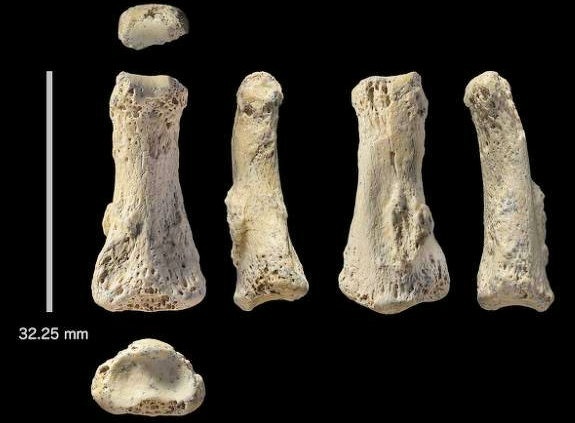

The Arabian Peninsula has long been considered the obvious route that early members of our species took as they trekked out of Africa and migrated to the Middle East and Eurasia. Stone tools have suggested ancient humans explored the Arabian Peninsula at various times in prehistory when the climate was wetter and its harsh deserts were transformed into green grasslands punctuated with freshwater lakes. Yet so far, researchers have only found a single human finger bone dating to 88,000 years to prove modern humans, rather than some other hominin toolmaker, lived there.

After a decade of scouring the Arabian Peninsula using satellite imagery and ground truthing, Petraglia and his international colleagues have identified tens of thousands of ancient freshwater lakebeds, including one in the Nefud dubbed "Alathar," meaning "the trace" in Arabic. Here, they spotted hundreds of footprints on a heavily trampled lakebed surface, which had recently been exposed when overlying sediments eroded. Almost 400 tracks were left by animals, including a wild ass, a giant buffalo, elephants, and camels. Only seven were confidently identified as human footprints. But by comparing the size and shape of these tracks with those made by modern humans and Neanderthals, the researchers conclude the tracks were likely made by people with longer feet, taller stature, and smaller mass: Homo sapiens, rather than Neanderthals, as they report today in Science Advances.

The age of the sediments also suggests H. sapiens made the tracks, the researchers say. Using a method called optically stimulated luminescence, which measures electrons to infer when layers of sediment were last exposed to light, the team dated the sediments above and below the footprints to 121,000 and 112,000 years. At that date, "Neanderthals were absent from the Levant [Middle East]," says co-author Mathew Stewart of the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology. "Therefore, we argue that H. sapiens was likely responsible for the footprints."

A lot rests on the dates, however. Geochronologist Bert Roberts of the University of Wollongong notes some uncertainties with dating methods at the site—including older ages for animal fossils and potential issues with calculating the precise rate of decay of uranium in the sediments. The dates for the footprints "might be in the right ballpark," he says, "but more could be done to validate them." The team can't entirely exclude Neanderthals, says paleoanthropologist Marta Mirazón Lahr of the University of Cambridge, because the fossil record is so spotty in Arabia. But she thinks H. sapiens is the more likely candidate.

Even more intriguing, she notes, the footprints show the humans were capable of moving long distances between Africa and Arabia and must have had fairly large foraging parties to have been able to penetrate deep into the rich interior wetlands of Arabia. The rare association of human and animal footprints laid down in the same day or so also offers a rare glimpse of a day in the life of an ancient human. Usually, animal and human fossils found in the same fossil bed were buried hundreds, if not thousands, of years apart and never laid eyes on each other. "These footprints give us a unique snapshot of the humans living in this area at the same time as the animals," says paleoanthropologist Kevin Hatala of Chatham University in Pittsburgh, an expert on ancient footprints. "That tight association in time is what's so exciting to me."

finger bones from Saudi Arabia

88,000-Year-Old Human Middle Finger Bone Found in Saudi Arabia

In 2016, archaeologists in Saudi Arabia announced the discovery of a human fossil bone — the middle section of the middle finger — which was dated to be 88,000 years old, the oldest evidence modern humans on the Arabian Peninsula, an official from the Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage told Al-Arabiya. The Saudis claimed it was the oldest human bone ever found. [Source: Jack Moore, Newsweek, August 19, 2016 -]

Jack Moore wrote in Newsweek: “Researchers from a joint Saudi-U.K. project, which included the Saudi archaeologists and University of Oxford experts, made the find at the Taas al-Ghadha site near to the northwestern Saudi city of Tayma. The project is an extension of the Green Arabia Project, which is studying sites near ancient lakes in the Nafud desert. Archaeologists began digging in the area in 2012. -

“Its historic discovery suggests that human life dated back as far as 325,000 years, head of the Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage Ali Ghabban said. He did not elaborate on why the find of a 88,000-year-old bone led to this assumption. The Board of the Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage, said that the discovery is “considered an important achievement for the Saudi researchers who participated in these missions and one of the most important outcomes of Prince Sultan’s support and care for the archaeology sector in the Kingdom.” -

While the Saudis are claiming to have found the oldest ever human bone, the oldest bone ever discovered belonging to the lineage that developed into human beings, the Homo genus, is a jaw bone found in Ethiopia in 2015. It is dated to 2.8 million years ago. The oldest modern human discovered at that time was a 195,000-year-old fossil from Ethiopia. Since then 300,000-year-old modern human fossils have been found in Morocco.

Ancient 51-Centimeter-Long Hand Ax from Saudi Arabia May Be World's Largest

In November 2023, archaeologists in Saudi Arabia announced they had discovered what may be the world's largest prehistoric hand ax. The stone tool measures 51.3 centimeters (20.2 inches) long and, despite its size, is easily held with two hands, according to a statement. Live Science reported: An international team of researchers found the basalt hand ax on the Qurh Plain, just south of AlUla, a region in northwest Saudi Arabia. Both of the hand ax's sides have been sharpened, suggesting that it could have been employed for cutting or chopping. However, it's still unclear how the stone tool was used and which species, for instance Homo erectus or Homo sapiens, crafted it. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, November 26, 2023]

It's also unknown how old the tool is, as "the handaxe requires much more research to determine an accurate date," Ömer Can Aksoy, an archaeologist and the excavation's project director, told Live Science. email. However, other tools found at the site may date to 200,000 years ago, according to the team's assessment of their form and characteristics, so it's possible that the hand ax dates also to the Lower or Middle Palaeolithic, Aksoy said.

Researchers nearly missed the enormous hand ax, which is 9.5 centimeters (3.7 inches) wide and 5.7 centimeters (2.2 inches) thick. "It was the last 15 minutes of our daily work and it was a hot day," Aksoy said. "Two of our team members found the giant handaxe lying over the surface of a sand dune." After hearing the team members' calls, the rest of the crew joined them and then excavated the area in depth. "We recorded 13 more handaxes on the site," Aksoy said. "Each team member took off their yellow vests in order to highlight the locations of each find over the sand dune."

While the other newly found hand axes were similar in style, they were smaller in size. "After the initial excitement when we discovered this remarkable object we carried out an initial search to see if other similar sized objects had been found," Aksoy said. While the search for large hand axes continues, "this might be one of the longest," he said.

Some of the World’s Oldest Animal Art Found in Arabia

In 2022, Archaeology magazine reported: Twelve panels depicting images of camels and wild donkeys are now known to be the oldest life-size animal reliefs in the world. By using techniques such as analyzing tool marks and erosion, as well as radiocarbon dating associated artifacts, researchers have dated the reliefs at what is known as the Camel Site to the middle of the sixth millennium B.C.—some 5,000 years earlier than they had originally thought. During the Neolithic period (ca. 8000–3000 B.C.), northern Arabia was much wetter than it is now, and nomads herded sheep, cattle, and goats and hunted abundant wildlife. Animals would have had a crucial role in the herders’ existence, which may help explain why they created the massive reliefs. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, January/February 2022]

Archaeologist Maria Guagnin of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History explains that the site was clearly used for centuries, and possibly even millennia, and new reliefs were periodically added or old ones re-carved when details began to fade. “I wonder if the site was visited regularly, but reliefs were only added on special occasions,” she says. “Or was it only visited for special occasions, when new reliefs were added or existing ones repaired?” Guagnin has no question, however, regarding the mastery displayed by the Neolithic artists, who worked high atop cliffs where they would never have been able to see the entire animal while carving it. “The level of naturalism and detail is astonishing,” she says, “and the technical skill and community effort involved in the creation of these reliefs is evidence of the importance of rock art in the social and symbolic life of the Neolithic herders of northern Arabia.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Saudi finger bones, CNN, Zhiren Cave fossils, Science Daily, Middle East migration routes, researchgate

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024