Home | Category: Muslim Art and Architecture / Arab Art

ISLAM ART PROHIBITIONS

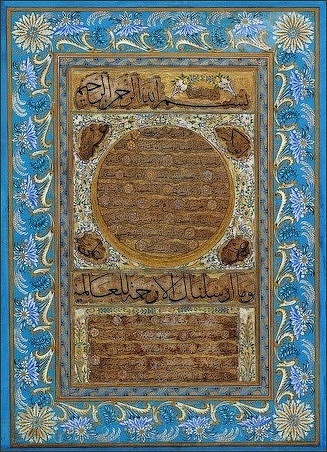

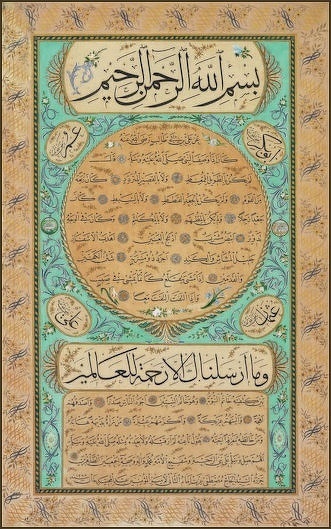

Hilya, the way Muhammad is depicted in the Muslim world

Muslims believe that only God creates. Only Allah has the power to give life. Extended to art this belief infers that any artist who paints pictures of people or animals is trying to outdo Allah himself and therefore deserves some of the worst punishments on the Day of Judgment. Some Muslims believe that when an artist, who has created animate objects, faces Allah in heaven, god will ask him to breath life into his creations. When the images remain lifeless the artist will be cast into hell.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The Islamic resistance to the representation of living beings ultimately stems from the belief that the creation of living forms is unique to God, and it is for this reason that the role of images and image makers has been controversial. The strongest statements on the subject of figural depiction are made in the Hadith (Traditions of the Prophet), where painters are challenged to "breathe life" into their creations and threatened with punishment on the Day of Judgment. The Qur’an is less specific but condemns idolatry and uses the Arabic term musawwir ("maker of forms," or artist) as an epithet for God. Partially as a result of this religious sentiment, figures in painting were often stylized and, in some cases, the destruction of figurative artworks occurred. Iconoclasm was previously known in the Byzantine period and aniconicism was a feature of the Judaic world, thus placing the Islamic objection to figurative representations within a larger context. As ornament, however, figures were largely devoid of any larger significance and perhaps therefore posed less challenge. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art \^/]

Initially Christians and Buddhists forbade images of humans and animals in their art for reasons similar to those endorsed by Muslims. Muslim prohibition of “false idols” mirrors similar prohibitions in Judaism and Old Testament Christianity. The first of the Ten Commandants reads, “Thou shall have no other gods before me,” followed by the second Commandment, “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven images”—interpreted by many as a ban on idolatry. During the Christian iconoclastic period many great works of art were destroyed. But later Christians saw the painting of religious figures as a way of glorifying God and teaching the illiterate masses about him, while Muslims continued to see it as an act of mockery. Buddhists raised the point that images of Buddha distracted Buddhists from their pursuit of nirvana. µ

A lot of good art has probably been destroyed by Islamic purists the same way the statues of Buddha were destroyed by the Taleban in Afghanistan. An issue of Time was once banned in some Muslim countries because it contained a reproduction of a woodcut of Muhammad.

Websites and Resources: Islamic Art and Architecture: Islamic Arts & Architecture /web.archive.org ; British Museum britishmuseum.org Islamic Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah/hd/orna ; Islamic Art Louvre Louvre ; Museum without Frontiers museumwnf.org ; Islamic Images islamicacademy.org ; Victoria & Albert Museum vam.ac.uk ; Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar mia.org.qa

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Islamic Art” by Jonathan Bloom and Sheila Blair Amazon.com ;

“Islamic Art: Architecture, Painting, Calligraphy, Ceramics, Glass, Carpets” by Luca Mozzati Amazon.com ;

“Islamic Geometric Design” by Eric Broug Amazon.com ;

“Islamic Design: A Genius For Geometry” by Daud Sutton Amazon.com ;

“Islamic Art of Illumination: Classical Tazhib From Ottoman to Contemporary Times”

by Sema Onat Amazon.com ;

“Arts and Crafts of the Islamic Lands” by Azzam Khaled Amazon.com ;

“The Art and Architecture of Islam, 1250-1800" by Jonathan Bloom and Sheila S. Blair Amazon.com ;

“Islamic Art and Architecture, 650–1250" by Ettinghausen, Richard, Oleg Grabar, and Marilyn Jenkins-Madina (2001) Amazon.com ;

“Islamic Art and Architecture” by Robert Hillenbrand Amazon.com ;

“The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture (1,400 Years, 500 Color Images) by Moya Carey Amazon.com

Idolatry and the Ban on Images of Animals and People in Islamic Art

Any picture or an animal or a person in a mosque or work or art is seen as idolatry. But the Qur’an doesn’t explicitly ban images of animals and people as is commonly thought. It warns against the creation and worship of idols. The ban is rooted in the belief that if someone makes an image they will worship it, a view spread by conservative Muslims after Muhammad’s death. According to the Hadiths, Ibn Abbas, an early disciple of Muhammad said, "The angels will not enter a house in which there is a picture of a dog."

Islam has an uncompromising belief in the oneness, or unity, of God (tawhid). Associating anything else with God is idolatry, considered the one unforgivable sin. To avoid any possible idolatry resulting from the depiction of figures, for example, Islamic religious art tends to use calligraphy, geometric forms, and arabesque designs and is thus abstract rather than representational. [Source: John L. Esposito “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Islamic painting with the face scratched off

One of Muhammad's most important acts was expelling the Kaaba of idols. One early Arabic source wrote the Kaaba contained paintings as well as statues and that Muhammad ordered them all destroyed except a mural of Jesus and the Virgin Mary which he spared, some suggest, so as not to offend his Christian converts. Presumably Muhammad and his successors had no problems with paintings. The movement to forbid painting, some say, was influenced by Jewish converts.

According to the Qur’an: "Those who endure the most grievances on the Day of resurrection are those who create a likeness." Idolatry ("shirk"in Arabic) is regarded as the handiwork of the devil. It is one of the worst sins and even the worship of Muhammad is sacrilegious. The only being that a Muslim is allowed to worship is Allah. Muslim prohibition of “false idols” mirrors similar prohibitions in Judaism and Old Testament Christianity. The first of the Ten Commandants reads, “Thou shall have no other gods before me,” followed by the second Commandment, “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven images.” Buddhists also raised that point that images of Buddha distracted Buddhists from their pursuit of nirvana.

Moslem scholar interpretation produced the blanket statement against all images of animals and people. Interpretations of the ban on idolatry and animal and human figures varies widely. The prophet reportedly allowed the depiction of animals on pillows, carpets and children's toys. Many Islamic cultures allowed images of animals and people to be used in non-religious buildings and works of art of created for private use. Some of the greatest works of Islamic art were miniature paintings of famous rulers, and court, hunting and battle scenes with lots of human figures found in manuscripts created for the private use of sultans and caliphs.

Sunnah on Vanities and Sundry Matters

The Sunnahs are the practices and examples drawn from the Prophet Muhammad's life. Along with the Hadiths they are the most important texts in Islam after the Qur’an. They must adhere to a strict chain of narration that ensures their authenticity, taking into account factors such as the character of people in the chain and continuity in narration. Reports that fail to meet such criteria are disregarded.

The Sunnah reads: “The angels are not with the company with which is a dog, nor with the company with which is a bell. A bell is the devil's musical instrument. The angels do not enter a house in which is a dog, nor that in which there are pictures. [Source: Charles F. Horne, ed., “The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East”, (New York: Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb, 1917), Vol. VI: Medieval Arabia, pp. 11-32]

“Every painter is in hell fire; and God will appoint a person at the day of resurrection for every picture he shall have drawn, to punish him, and they will punish him in hell. Then if you must make pictures, make them of trees and things without souls.”

Bonfire of the Vanities and Photography

Allah written in Arabic calligraphy

The expression "bonfire of the vanities" refers to the destruction of images and idols by Muslims in the 7th century. After converting to Islam, the new Muslim's not only tore down pictures of people and animals in their homes and places of worship, they also removed figures from their saddles and dishes. Jewish converts to Islam reinforced this conviction with their belief in Second Commandment which forbids the worship of idols.µ

Photography is immune from declaration because it was invented long after the Qur’an was written. "When photography appeared in the nineteenth century," says historian Daniel Boorstein, "it offered a new challenge to the mullah's theological gymnastics." Muslims who wished to be photographed said that the photographs were made by Allah with his creation the sun. Despite this photographs are still frowned upon in much of the Muslim world because, like paintings, they are "creations" of human forms which only Allah is allowed to make. Some Muslims also believe that photographs are immodest and they steal a person's soul.µ

In modern times Muslim scholars have said it is alright for medical schools to use books with anatomical pictures of people and police to use to "Wanted Posters" to apprehend criminals. Even the Taliban allowed passport photographs.

Figural Representation in Islamic Art

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “With the spread of Islam outward from the Arabian Peninsula in the seventh century, the figurative artistic traditions of the newly conquered lands profoundly influenced the development of Islamic art. Ornamentation in Islamic art came to include figural representations in its decorative vocabulary, drawn from a variety of sources. Although the often cited opposition in Islam to the depiction of human and animal forms holds true for religious art and architecture, in the secular sphere, such representations have flourished in nearly all Islamic cultures. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art \^/]

As with other forms of Islamic ornamentation, artists freely adapted and stylized basic human and animal forms, giving rise to a great variety of figural-based designs. Figural motifs are found on the surface decoration of objects or architecture, as part of the woven or applied patterns of textiles, and, most rarely, in sculptural form. In some cases, decorative images are closely related to the narrative painting tradition, where text illustrations provided sources for ornamental themes and motifs. As for manuscript illustration, miniature paintings were integral parts of these works of art as visual aids to the text, therefore no restrictions were imposed. A further category of fantastic figures, from which ornamental patterns were generated, also existed. Some fantastic motifs, such as harpies (female-headed birds) and griffins (winged felines), were drawn from pre-Islamic mythological sources, whereas others were created through the visual manipulation of figural forms by artists.\^/

Images of People and Animals in Islamic Art

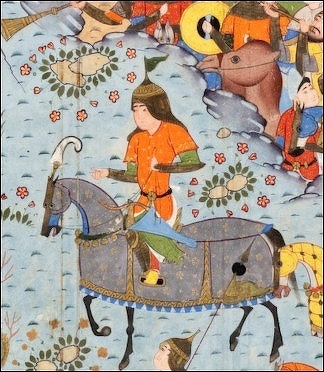

Sassanid prince Anoshazad in the Shahnameh, a text made by Persian Muslims

The artwork from pre-Islamic civilizations were mostly idols and pieces with beautiful flowing script. Despite the restrictions on idolatry images of animals were common in Muslim courts. Some of the first caliphs had frescoes of dogs painted in their homes and pleasure boats made in the shape of lions. Caliph Muqtadir (908-932) had a tree made from silver and gold, decorated with precious stones shaped like fruit and animals, built in his palace. Caliph Mustansir (1035-1094) had a ceremonial tent decorated with all the world's known animals that took 150 workmen nine years to finish.µ

Muslims in the Ottoman and Persian Empires in the 15th and 16th centuries produced a wonderful collection of art representing episodes from Muhammad’s life complete with images of Muhammad, angels, animals and ordinary people.

Ottoman sultans commissioned portraits of themselves and illustrated records of historical events and battles. Titian painted a portrait of Süleyman the Magnificent and Gentile Bellini painted Muhammad II. The public however did not know about these works of art. It was rationalized that it wasn't necessarily a sin to possess these works of art, it was only a sin to display them ostentatiously. This same reasoning was used to justify gambling, drinking, the making of eunuchs and womanizing (also against Muslim law) in private.µ

The sultans and caliphs kept their images small under the understanding that images of living things were harmless if they did not cast a shadow. One of the most unusual world of art that did not fit this description was a three foot incense burner shaped like three legged helmet-headed monster that the Seljuk prince who owned it could "bring to life" whenever he wanted.

Human and animal figures are more likely yo be seen in secular art than religious art and sometimes use as a criteria to distinguish them.

Sexy Human Images in Islamic Art

In 2007, an exhibit called “Spirit & Life” at the Ismaili Center in South Kensington, London highlighted not only the human form but the human form in erotic Islamic art. Much of the art was from the personal collection of the Aga Khan’s uncle, Prince Sadruddin.

pdated March 2024

"Lovers in a Landscape"

Describing a Mughal painting create in 1646 called “Lovers in a Landscape” Michael Glover, art critic for the Times of London, wrote:“Two lovers are leaning into each other. There is wine and a wine glass. The woman is repeatedly burning her lover’s arm. Physical love may well be a metaphor for man’s love of the Almighty, but there is no denying that this painting depicts passionate physical love.

Describing a worked painted by the Mughal artist between 1618 and 1620 Glover wrote: “A miniature of a bent old man...shows him seemingly as a pilgrim communicating with a flower, which peers back at him...It has naturalism, lots of volume and shading.”

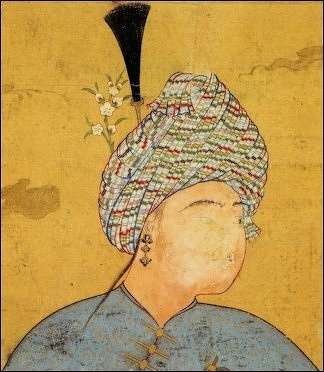

Muhammad’s Appearance

Producing images of Muhammad is considered a form of idolatry and is this sacrilegious. Even so a few images of him exist, mostly from Persia. They depict a man with Asian features and reddish beard, wearing a large green turban and a cloak. These representations reflect the area and era they were produced more than they are true likenesses of Muhammad.

In some ways visual images of Muhammad are not so necessary as written descriptions of him abound. Suleyman Dost wrote: “Most Muslims pictured Muhammad as described by his cousin and son-in-law Ali in a famous passage contained in the Shama'il al-Muhammadiyya: a broad-shouldered man of medium height, with black, wavy hair and a rosy complexion, walking with a slight downward lean. The second half of the description focused on his character: a humble man that inspired awe and respect in everyone that met him. [Source: Suleyman Dost, Assistant Professor of Classical Islam, Brandeis University, The Conversation, May 30, 2021]

According to description of him by his companions and admirers that appeared after his death, Muhammad was tall, strong and lean. He had a long beard and serious eyes. W. Montgomery Watt, Professor of Arabic and Islamic studies at the University of Edinburgh, wrote in “Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman”:“Muhammad, according to some apparently authentic accounts, was of average height or a little above the average. His chest and shoulders were broad, and altogether he was of sturdy build. His arms were long, and his hands and feet rough. His forehead was large and prominent, and he had a hooked nose and large black eyes with a touch of brown. The hair of his head was long and thick, straight or slightly curled. His beard also was thick, and he had a thin line of fine hair on his neck and chest. His cheeks were spare, his mouth large, and he had a pleasant smile. In complexion he was fair. [Source: W. Montgomery Watt (1909-2006), “Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman,” Oxford University Press, 1961. from pg. 229. \~]

Images and Hilya (Textual Portraits) of Muhammad

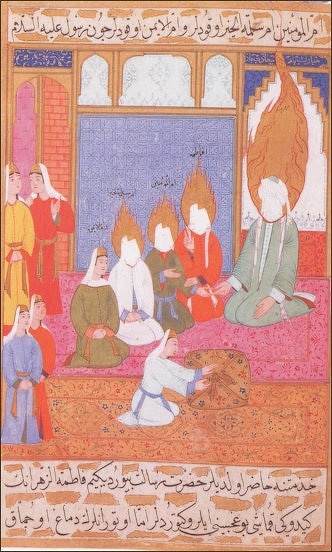

Muhammad preaching: the men have their faces covered but not the women

Traditional Islam does not depict the Prophet Muhammad in any media, although artists from other faiths and cultures have made likenesses of him. There are depictions of him in some Muslim, mainly Persian, texts. Suleyman Dost wrote “Figurative portrayals of Muhammad were not entirely unheard of in the Islamic world. In fact, manuscripts from the 13th century onward did contain scenes from the prophet’s life, showing him in full figure initially and with a veiled face later on. The majority of Muslims, however, would not have access to the manuscripts that contained these images of the prophet. For those who wanted to visualize Muhammad, there were nonpictorial, textual alternatives.[Source: Suleyman Dost, Assistant Professor of Classical Islam, Brandeis University, The Conversation, May 30, 2021]

“There was an artistic tradition that was particularly popular among Turkish- and Persian-speaking Muslims. Ornamented and gilded edgings on a single page were filled with a masterfully calligraphed text of Muhammad’s description by Ali in the Shama'il. The center of the page featured a famous verse from the Qur’an: “We only sent you (Muhammad) as a mercy to the worlds.”

“These textual portraits, called “hilya” in Arabic, were the closest that one would get to an “image” of Muhammad in most of the Muslim world. Some hilyas were strictly without any figural representation, while others contained a drawing of the Kaaba, the holy shrine in Mecca, or a rose that symbolized the beauty of the prophet.

“Framed hilyas graced mosques and private houses well into the 20th century. Smaller specimens were carried in bottles or the pockets of those who believed in the spiritual power of the prophet’s description for good health and against evil. Hilyas kept the memory of Muhammad fresh for those who wanted to imagine him from mere words.

Different Interpretations of Making Images of Muhammad

Suleyman Dost wrote “The Islamic legal basis for banning images, including Muhammad’s, is less than straightforward and there are variations across denominations and legal schools. It appears, for instance, that Shia communities have been more accepting of visual representations for devotional purposes than Sunni ones. Pictures of Muhammad, Ali and other family members of the prophet have some circulation in the popular religious culture of Shia-majority countries, such as Iran. Sunni Islam, on the other hand, has largely shunned religious iconography. [Source: Suleyman Dost, Assistant Professor of Classical Islam, Brandeis University, The Conversation, May 30, 2021]

“Outside the Islamic world, Muhammad was regularly fictionalized in literature and was depicted in images in medieval and early modern Christendom. But this was often in less than sympathetic forms. Dante’s “Inferno,” most famously, had the prophet and Ali suffering in hell, and the scene inspired many drawings. These depictions, however, hardly ever received any attention from the Muslim world, as they were produced for and consumed within the Christian world.

In recent years there has been protests and violence over the images — often unflattering ones — of Muhammad. In August 2020, caricatures of Muhammad in French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo led to the stabbing deaths of two people near the former headquarters of the magazine and the beheading of a teacher who he showed the cartoons during a classroom lesson. “With advances in mass communication and social media, the spread of the images is swift, and so is the mobilization for reactions to them.

Many Muslims find the caricatures offensive for its Islamophobic content. Some of the caricatures draw a coarse equation of Islam with violence or debauchery through Muhammad’s image, a pervasive theme in the colonial European scholarship on Muhammad. Anthropologist Saba Mahmood has argued that such depictions can cause “moral injury” for Muslims, an emotional pain due to the special relation that they have with the prophet. Political scientist Andrew March sees the caricatures as “a political act” that could cause harm to the efforts of creating a “public space where Muslims feel safe, valued, and equal.”

Images of Muhammad in Art

Another Hilya of Muhammad

The Prophet Muhammad has been represented in Islamic paintings since the 13th century. One 14th-century image depicts Muhammad receiving the beginning of Qur’anic revelations from God through the angel Gabriel. In Islamic thought, it is at that moment that Muhammad became a divinely appointed prophet. The is part of a royal manuscript, the “Compendium of Chronicles,” written by Rashid al-Din. It is one of the earliest illustrated histories of the world. The manuscript includes numerous paintings, including a cycle of images depicting several key moments in the Prophet Muhammad’s life. The painting depicts the prophet with his facial features visible as the angel Gabriel approaches him to convey God’s divine word. The event is shown taking place outdoors in a rocky setting that matches the accompanying text’s description. [Source: Christiane Gruber, Professor of Islamic Art, University of Michigan, The Conversation, January 10, 2023]

Another image, made in Ottoman lands in 1595-96, is part of a six-volume biography of the prophet. Over 800 paintings in this manuscript depict major moments in Muhammad’s life, from his birth to his death. In that painting, Muhammad is seen raising his hands in prayer while standing on the Mountain of Light, known as Jabal al-Nur, near Mecca. His facial features are no longer visible; instead, they are hidden behind a facial veil. The Ottoman artist chose to depict the prophet’s purity through the use of white fabrics, and his entire being as touched by the light of God via the large flaming nimbus that encircles his body. Jabal al-Nur is shown, as its name suggests, as a radiant elevation. Above it and beyond the clouds, rows of angels hover in praise.

In January 2023, Hamline University in St. Paul, Minnesota dismissed Erika López Prater, an adjunct faculty member, for showing these two historical Islamic paintings of the Prophet Muhammad in her global survey of art history. Following complaints from some Muslim students, university administrators described such images as disrespectful and Islamophobic.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, Encyclopedia.com, The Conversation, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Library of Congress and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024