Home | Category: Medieval Period / Colonialism and Slavery / The Crusades

ACCOUNTS OF SALADIN’S CAPTURE OF JERUSALEM

In "Some Medieval Accounts of Salah al-Din's Recovery of Jerusalem”, Hadia Dajani-Shakeel wrote: “The accounts of the actual capture of Jerusalem are varied with respect to the perspective from which they were written and the details they give. However, despite some discrepancies, they cohere and complement one another. [Source: Hadia Dajani-Shakeel. "Some Medieval Accounts of Salah al-Din's Recovery of Jerusalem (Al-Quds)", “Studia Palaestina: Studies in honour of Constantine K. Zurayk,” edited by Hisham Nashabe, Institute for Palestine Studies, Beirut 1988 ]

“The Arabic accounts give us general information about Salah al- Din's attack on Jerusalem, but they fail to identify the exact locations of some of his battles and other important information about the Latins in the city, as well as about Salah al-Din's contacts with the Arab-Christian community in Jerusalem. In order to complete this picture we will utilize the chronicle of Ernoul (Chroniquc d'Er- noul). Ernoul (d. A.D. 1230) was the squire of Balian of Ibelin, the Latin leader who negotiated the surrender of Jerusalem to Salah al- Din. He was an eyewitness to the battle of Jerusalem and provides insight into what was happening within the walled city,.

“There is some measure of coherence among the Arabic accounts as well as between the Arabic accounts and Ernoul's account. The consistency of these accounts itself supports their claim to authenticity. In addition to the medieval accounts, we will also use, wherever possible, modern sources that have utilized accounts in Latin.

See Separate Article: SALADIN AND THE MUSLIMS RETAKE JERUSALEM IN THE 12TH CENTURY africame.factsanddetails.com

Jerusalem in the Summer of 1187: Before Saladin’s Offensive

In "Some Medieval Accounts of Salah al-Din's Recovery of Jerusalem”, Hadia Dajani-Shakeel wrote: Salah al-Din's decisive victory at Hittin on Saturday, 24 Rabi' al- Thani, A.H. 583/4 July, A.D. 1187 opened the way for him to reconquer the rest of Palestine. Thus, within a period of two months, from July to September, he recovered all the inland cities and fortresses except Jerusalem, al-Karak, and al-Shawbak in Transjordan, as well as some fortresses in the north, like Kawkab (Belvoir) and Safad. He also recovered all major ports between 'Asqalan and Jubayl except Tyre.2 In so doing, he cleared the land route between Egypt and Palestine for the movement of his troops and established his fleet in the Mediterranean between Alexandria and Acre. His fleet went into action immediately (Jumada al-Thani, A.H. 583/September, A.D. 1187) and blocked the movement of European ships in the area under its control. [Source: Hadia Dajani-Shakeel. "Some Medieval Accounts of Salah al-Din's Recovery of Jerusalem (Al-Quds)", “Studia Palaestina: Studies in honour of Constantine K. Zurayk,” edited by Hisham Nashabe, Institute for Palestine Studies, Beirut 1988]

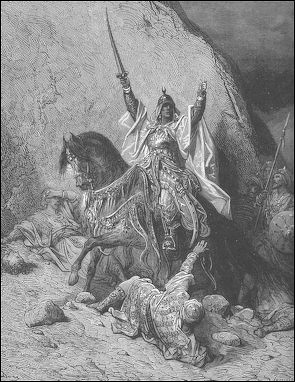

Saladin, the Victorius

“Jerusalem, the capital of the Latin kingdom, had suffered a great loss of manpower as a result of Hittin. Among those captured or killed were the king, Gui of Lusignan; his counsellors; his brother Amaury, the constable of the kingdom; the grand masters of the Templars and the Hospitallers, and a large number of the knights of these two military orders. The only surviving leaders, who fled the battle to safety through Muslim lines, were Raymond of Tripoli, Reynold of Sidon, and Balian of Ibelin (referred to in Arabic sources as Balian Ibn Barzan). These men had enjoyed friendly relations with Salah al-Din and were suspected by the Latins of complicity with him. Of the three, the most important for our discussion is Balian.

“While Salah al-Din mopped up Crusader strongholds in Palestine after the battle of Hittin, Jerusalem was placed under a temporary government, with Queen Sybil, wife of Gui of Lusignan, as the ruler along with Heraclius, the controversial and unpopular patriarch. The city faced many problems. In addition to the loss of most of its male population, it suffered from a shortage of food because the battle of Hittin had occurred at harvest time and, accordingly, the crops were lost.

“The shortage of food and supplies became more acute as refugees poured into Jerusalem from most of the areas surrounding it. Some of these refugees must have gone to Jerusalem seeking shelter within its walls, while others presumably went to defend the city, just as native Palestinians had done ninety years earlier. The city, which could accommodate a population of about 30,000, became the residence of about 60,000 persons, according to estimates of Arab chroniclers. As Runciman indicates, there were fifty women and children for every man. Refugees so crowded the streets, the churches, and the houses that the walled city could hardly accommodate them. According to Ibn al-Athir's somewhat exaggerated description, when Salah al-Din's forces approached the city, "they saw on the wall a terrifying crowd of men and heard an uproar of voices coming from the people inside the wall, which led them to infer that a large population was assembled there.''

Contacts Between Saladin and the Christians Holding Jerusalem

In "Some Medieval Accounts of Salah al-Din's Recovery of Jerusalem”, Hadia Dajani-Shakeel wrote: “Faced with all these problems, Jerusalem could not have resisted an attack by Salah al-Din for very long. Realizing this, its authorities tried to establish contact with Salah al-Din to discuss the future of the city. We have two different accounts of their efforts. The first, by Abu Shamah, who quotes al-Qadisi, indicates that Salah al-Din had said in a letter to a relative that the sovereign of Jerusalem (Malik al-Quds) had contacted him during his attack on Tyre (Jumada al-Thani, A.H. 583/August, A.D. 1187) to ask for safe conduct (aman), and that Salah al-Din had responded, "I will come to you in Jerusalem." According to al-Qadisi, the astrologers informed Salah al-Din that the stars indicated he would enter Jerusalem but that he would lose one eye. To this Salah al-Din responded, "I would not mind losing my sight if I took the city." Only the siege of Tyre prevented him from going to Jerusalem. [Source: Hadia Dajani-Shakeel. "Some Medieval Accounts of Salah al-Din's Recovery of Jerusalem (Al-Quds)", “Studia Palaestina: Studies in honour of Constantine K. Zurayk,” edited by Hisham Nashabe, Institute for Palestine Studies, Beirut 1988 ]

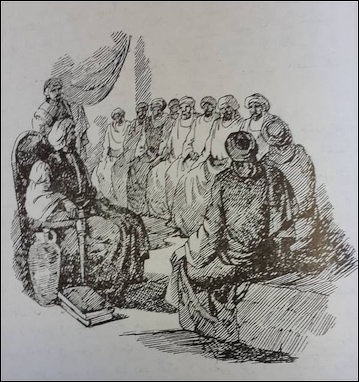

Saladin council

“The second account is by Emoul, the Latin chronicler who was in Jerusalem during Salah al-Din's invasion of the Latin kingdom, and it provides details that do not appear in the Arabic sources. Ernoul indicates that a delegation of citizens from Jerusalem went to see Salah al-Din on the day he took 'Asqalan (Jumada al-Thani, A.H. 583/September, A.D. 1187) to ask for a peaceful solution for Jerusalem. On the day of the meeting there was an eclipse of the sun, which the Latin delegates considered to be a bad omen. Never- theless, Salah al-Din offered them generous terms for the city: They were to be allowed to remain in the city temporarily, they were to retain the land within a radius of five leagues around it, and they were to receive the supplies they needed from Salah al-Din. The settlement was to remain valid until Pentecost. If the citizens of Jerusalem could obtain external help, they would remain rulers of the city; if not, they were to surrender it and remove themselves to Christian lands. According to Ernoul, the delegation rejected this offer, saying they would never give up the city in which "the Lord died for them." Salah al-Din then vowed to take Jerusalem by force and started his march against the city.

“It seems most probable that there was more than one contact between Salah al-Din and the authorities in Jerusalem, the first being in Tyre. 'Imad al-Din informs us that while at Tyre Salah al-Din summoned King Gui and the grand master of the Templars and promised both of them freedom if they helped him secure the surrender of other cities. These two did in fact later help him to secure the surrender of 'Asqalan and Gaza. Salah al-Din may at the same time also have contacted Balian of Ibelin, who was already in Tyre, and asked him to secure the surrender of Jerusalem. Ernoul mentions that while Salah al-Din was in Tyre, Balian sought his permission to go to Jerusalem in order to rescue his wife, Maria Comnena, as well as other members of his family and their possessions. Salah al-Din granted him permission to go to Jerusalem on the condition that he not bear weapons against him and that he spend only one night there.

“In so doing, Salah al-Din must have hoped to use Balian as his chief negotiator for the surrender of Jerusalem. Balian ultimately did negotiate the surrender of the city, but only after he had broken his agreement with Salah al-Din and played a dramatic role in its defence.

Jerusalem Prepares for Saladin’s Assault

Hadia Dajani-Shakeel wrote: “After arriving in Jerusalem, Balian was pressed by the patriarch to remain there and to mobilize the population for its defence. At first Balian resisted, insisting that he would adhere 10 his commitment to Salah al-Din. But at the insistence ol the patriarch, who absolved him of his oath, Balian finally consented to accept the leadership of the city. His rank among the Latins was, according to Ibn al-Athir, analogous to that of a king. [Source: Hadia Dajani-Shakeel. "Some Medieval Accounts of Salah al-Din's Recovery of Jerusalem (Al-Quds)", “Studia Palaestina: Studies in honour of Constantine K. Zurayk,” edited by Hisham Nashabe, Institute for Palestine Studies, Beirut 1988 ]

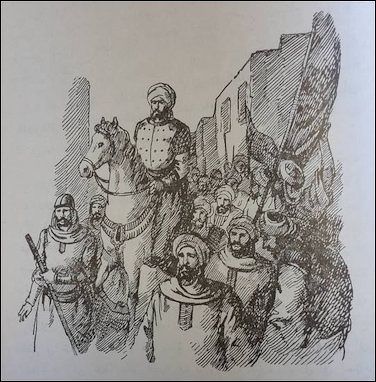

Saladin marches to Jerusalem

“Balian began immediately to consolidate the Latin forces and plan the defence of the city. According to Latin sources, he found only two knights in the city who had survived Hittin. Thus, to make up for the shortage of male fighters, he knighted fifty sons of the nobility. According to Runciman, he knighted every boy of noble origin who was over sixteen years of age; he also knighted sixty burgesses. Since money was scarce, Balian, with the blessing of the Patriarch Heraclius, stripped the silver from the roof of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and used it, along with some church funds and money that King Henry II of England had sent to the Hospitallers, to produce a currency. He then distributed arms to every able-bodied man in the city.

“As the undisputed ruler of Jerusalem, Balian is most likely to have contacted Salah al-Din once again regarding Jerusalem at 'Asqa- lan. According to Latin sources, Balian wrote him at 'Asqalan to apologize for having broken his agreement and to ask his forgiveness, which Salah al-Din gave.2

“No one knows the nature of the secret correspondence between the two leaders, but the terms that Ernoul alleges Salah al-Din to have proposed, regarding the fate of Jerusalem, seem doubtful. Salah al-Din was by then well aware that Jerusalem would not be able to hold out against him for long, especially since he had isolated it almost completely. Nor would he have allowed a situation to develop in Jerusalem such as that in Tyre, which had become the centre of resistance against his forces. Furthermore, even before the capture of 'Asqalan, Salah al-Din had written to the caliph and to other relatives announcing his intention to capture the city. In one letter he stated, "The march to Jerusalem will not be delayed, for this is precisely the right time to liberate it."

“Ernoul's account need not be taken as a contradiction of other accounts. Moreover, although it raises many questions, one cannot discount it. Hence, it seems quite likely that a Latin delegation went to 'Asqalan proposing the kind of terms that Ernoul attributed to Salah al-Din, that Salah al-Din rejected them, and that the authorities in Jerusalem began their preparations for the defence of the city.

Saladin Arrives in Jerusalem Area

Hadia Dajani-Shakeel wrote: “After capturing 'Asqalan on 16 Jumada al-Thani, A.H. 583!5 September, A.D. 1187 and arranging for its administration and settlement, Salah al-Din summoned all his forces, which were then dispersed along the coast between 'Asqalan and Jubayl. They joined him, according to Ibn Shaddad, "after having fulfiled their desires in pillaging and raiding," and he then marched on Jerusalem, "entrusting his affairs to God and anxious to profit by the opportunity of finding the door of righteousness opened." Salah al-Din marched in a great procession accompanied by his knights, sons, brothers, mamlukes, commanders, and friends in "squadrons ranked according to their merit, in platoons drawn up in solemn cavalcades . . . with yellow flags that signalled disaster to the Banu al-Asfar." [Source: Hadia Dajani-Shakeel. "Some Medieval Accounts of Salah al-Din's Recovery of Jerusalem (Al-Quds)", “Studia Palaestina: Studies in honour of Constantine K. Zurayk,” edited by Hisham Nashabe, Institute for Palestine Studies, Beirut 1988 ]

“As they were approaching Jerusalem, however, the vanguard of the army, unaware of the presence of Latin scouts, was ambushed near al-Qubeiba and sustained heavy losses. Ibn al-Athir, who mentions this incident without indicating its location, notes that one of Salah al-Din's commanders, an amir, was killed along with some of his men. This incident grieved Muslims greatly.

“Upon reaching Jerusalem Salah al-Din enquired about the location of al-Aqsa mosque and the shortest route to it, "which is also the shortest route to Heaven." As 'Imad al-Din reports, he swore to bring back to the sacred shrines their old grandeur and vowed not to leave Jerusalem until he had recovered the Dome of the Rock, "from which the Prophet had set foot," raised his flag on its highest point, and visited it personally.

“According to Arabic sources, Salah al-Din arrived from 'Asqalan at the western side of the city on Sunday, 15 Rajab, A.H. 583/21 September, A.D. 1187, although, according to Ernoul, he arrived on Thursday evening, 12 Rajab, A.H. 583/18 September, A.D. 1187. The next day, Ernoul says, Salah al-Din ranged his forces opposite the western wall of Jerusalem, where he subsequently started his attack. Arabic chroniclers do not tell us the exact location of Salah al-Din's forces in the first few days of combat, but Ernoul states that they were stationed opposite the western wall between David's Gate (Bab al-Khalil) and St. Stephen's Gate (Bab al-'Amud). More specifically, they were facing the hospital for leper women behind David's Gate and that for leper men near St. Stephen's Gate.

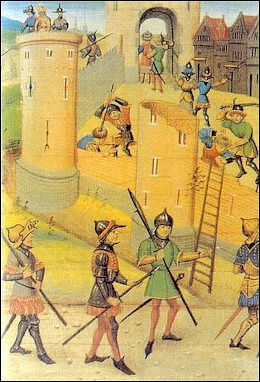

Fighting Around the Western Wall of Jerusalem

Hadia Dajani-Shakeel wrote: “The western side of the city was well fortified because of its geographical location. Al-Qadi al-Fadil describes it as follows: "From this side of the city, where he [Salah al-Din j had encamped, he saw a deep valley, a precipice rugged and profound, with a wall which encircled the city like a bracelet, and towers which represented the larger pearls of the necklace worn by that place of residence." [Source: Hadia Dajani-Shakeel. "Some Medieval Accounts of Salah al-Din's Recovery of Jerusalem (Al-Quds)", “Studia Palaestina: Studies in honour of Constantine K. Zurayk,” edited by Hisham Nashabe, Institute for Palestine Studies, Beirut 1988 ]

“This location was extremely difficult for Salah al-Din's army, or any other, to attack, for it enclosed two towers. The first was David's Tower (al-Qal'a), which was impregnable, and the second was Tancred's Tower. According to a twelfth-century Latin pilgrim, David's Tower contained two hundred steps leading to the summit and formed the main defence of the city. It was very heavily guarded in times of both peace and war. During the confrontation with Salah al-Din most of the Latin fighters were stationed in David's Tower. This same citadel had been attacked by Raymond of Toulouse, ninety years before Salah al-Din, and had been taken from its defenders only after they had surrendered.

“This part of the western wall gave the Latins other advantages as well. According to Ernoul, they had the sun to their backs, while Salah al-Din's forces were facing it. This fact determined to some extent the pattern of battle, for the Latins attacked the forces of Salah al-Din in the morning, trying to push them away from the walls, while Salah al-Din's forces attacked the Latins in the afternoon and continued the fight until nightfall.

“The Latins had the upper hand at first. Writing of some of the battles between the two sides, 'Imad al-Din hints at the courage of the enemy: "They challenged [us I to combat and barred the pass. They came down into the lists like enernies. They slaughtered and drew blood. They blazed with fury and defended the city .... They drove us back and defended themselves. They became inflamed and caused us harm, groaned, incited, and called for help in a foreign tongue.... They clustered together and obstinately stood their ground. They made themselves a target for arrows and called on death to stand by them. They said: "Each one of us is worth 20, and every ten is worth 200! We shall bring about the end of the world in defence of the church of resurrection." So the battle continued, as well as slaughter with spear and sword."

“Ernoul provides additional details of the battle at the western wall. He says that Salah al-Din had at first warned the authorities in Jerusalem and asked them to surrender, but they had rejected his request because they were very well armed and fortified. Salah al-Din then ordered his troops to attack the city. They tried to reach the gates several times but failed. The Latins, in turn, tried to make sorties but were repulsed.

Saladin Changes His Attack Position

Hadia Dajani-Shakeel wrote: “As the fighting raged, Salah al-Din travelled around the city in an attempt to find a more suitable location for his attack. After one week, according to Ernoul, or five days, according to the Arab chroniclers — he decided to reposition his forces. Abandoning their old encampment between David's Gate and St. Stephen's Gate his troops camped in a triangular area at the northeastern corner of the city, where, Ernoul tells us, they were facing the area between the Postern of St. Mary Magdalen (Bab al-Sahira) and the Gate of Jehoshafat (Bab al-Asbat). According to al-Qadi al-Fadil, this area was more accessible and better suited to the movement of cavalry. Salah al-Din pitched his tent very close to the city walls so that it could be reached easily by the weapons of the enemy. [Source: Hadia Dajani-Shakeel. "Some Medieval Accounts of Salah al-Din's Recovery of Jerusalem (Al-Quds)", “Studia Palaestina: Studies in honour of Constantine K. Zurayk,” edited by Hisham Nashabe, Institute for Palestine Studies, Beirut 1988 ]

“The new location, on the Mount of Olives (Jabal al-Zaytun), was quite high, according to Ernoul, so that from it Salah al-Din was able to watch the movement of the Latin forces insidc the city walls, except in those streets that were covered. Furthermore, in this location Salah al-Din's forces had their backs to the sun, while the Latins were facing its glare.

“In addition, a demographic factor made it more favourable to Salah al-Din. The northern triangular section of the city, which extended between St. Stephen's Gate and the Gate of Jehoshafat and which was known in medieval times as the Juiverie, enclosed the quarters of the native Christians. Often referred to in medieval chronicles as 'Syrians," they formed the most underprivileged community in Jerusalem under Latin rule and were despised by their Latin neighbours. Medieval Latin pilgrims placed them at the bottom of the demographic scale next to Muslims, or "Saracens."

“The native Christians were more inclined towards Salah al-Din than towards the Latins. For besides their hostile relations with the Latins and their linguistic and ethnic identification with the Arabs of the area, they were also influenced by the Greek Orthodox Church in Byzantium. Byzantium at this time was an ally of Salah al-Din. The Emperor Isaac II Angelus had confirmed an agreement with Salah al-Din in A.D.1185, according to which Salah al-Din offered to convert existing Latin churches in the Holy Land to the Christian rite once they had been recovered.

Saladin Launches His Decisive Attack on Jerusalem

Hadia Dajani-Shakeel wrote: “Once in Jerusalem, Salah al-Din seems to have contacted the leaders of the native Christian community through an Orthodox Christian scholar from Jerusalem, known as Joseph Batit. Batit, as Runciman says, had even secured a promise from the leaders of the community that they would open the gates of the city in the vicinity of Salah al-Din, but this did not take place because the R Latins decided to surrender the city. [Source: Hadia Dajani-Shakeel. "Some Medieval Accounts of Salah al-Din's Recovery of Jerusalem (Al-Quds)", “Studia Palaestina: Studies in honour of Constantine K. Zurayk,” edited by Hisham Nashabe, Institute for Palestine Studies, Beirut 1988 ]

“On Friday, 20 Rajab, A.H. 583/25 September, A.D. 1187, Salah al-Din set up his mangonels and started his attack on the city. Ibn Shaddad gives a brief account of the battle, stating only that Salah al-Din pressed his attack on the city in hand-to-hand combat and through the use of archers, until a breach was made in the wall facing the Jehoshafat Valley (Wadi Jahannam) in a northern village. Realizing the inevitability of their defeat, the besieged Latins decided to ask for safe conduct and thus sent messengers to Salah al-Din to ask for a settlement. An agreement was soon reached.

“Ibn al-Athir's account of the battle is more detailed. According to him, on the night of 20 Rajab, A.H. 53/25 September, A.D. 1187 Salah al-Din installed his mangonels, and by morning his machinery was functional. The Latins also installed their mangonels on the wall and started to fire their catapults. Both sides fought bravely, each considering its struggle to bc in defence of its faith. The Latin cavalry left the city daily to engage in combat with Salah al-Din's forces, and both sustained casualties.

“In one of these battles a Muslim commander, 'Izz al-Din 'Isa Ibn Malik, was martyred by the Latins. His death so grieved the Muslims that they charged the Latins vehemently, forcing them away from their positions and pushing them back into the walls of the city. The Muslims crossed the moat and reached the wall. Sappers prepared to destroy it while archers gave them cover, and mangonels continued bombarding the Latins to drive them away from the wall so the sappers could complete their work. When the wall had been breached, sappers filled it witll wood.

Saladin’s Force Breach the Walls and Take Jerusalem

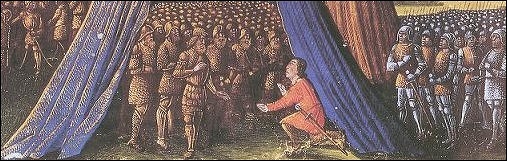

Hadia Dajani-Shakeel wrote: “Realizing that they were on the verge of perishing, the Latin leaders met in council and agreed to surrender Jerusalem to Salah al-Din and to ask him for safe conduct. Accordingly, they sent a delegation of their leaders to speak with Salah al-Din, but he turned them away, saying that he would treat them the way their anccstors had treated the residents of Jerusalem in A.H. 492/A.D. 1099, by death and captivity. On the following day, Balian Ibn Barzan (Balian of Ibelin) left Jerusalem to discuss the future of the city and its population with Salah al-Din. [Source: Hadia Dajani-Shakeel. "Some Medieval Accounts of Salah al-Din's Recovery of Jerusalem (Al-Quds)", “Studia Palaestina: Studies in honour of Constantine K. Zurayk,” edited by Hisham Nashabe, Institute for Palestine Studies, Beirut 1988 ]

“Al-Qadi al-Fadil gives us an account that differs slightly from that of Ibn al-Athir. According to him, the authorities in Jerusalem first sent a message to Salah al-Din offering to pay tribute for a limited period. This was only a delaying tactic until they could secure external help, however, and Salah al-Din, perceiving their intentions, rejected the offer and positioned his mangonels closer to the wal1.

“According to al-Qadi al-Fadil, the fire from the mangonels destroyed thc tops of the towers, "which were used to repel the attacks." When they collapsed, "the towers made such a noise that even the deafest among the enemy must have heard it." The defenders thus had to abandon their positions, giving the sappers a chance to accomplish their task. When the wall fell, Balian Ibn Barzan, the leader of the besieged, left the city and told Salah al-Din that Jerusalem should be taken by surrender rather than by force.

“Before discussing the negotiations between Salah al-Din and Balian, we shall present the viewpoint of the Latin chroniclers, which supplements the Arabic accounts. Although Ernoul and the author of Libellus agree with the Arabic accounts, they give us more details about the last stages of the war and the resulting negotiations. Ernoul says that the battle at the northeastern corner of the city lasted one week. The author of Libellus notes that Salah al-Din divided his forces, using 10,000 archers or more, "well armed down to their heels," to shoot at the walls. At the same time, according to Ernoul, about 10,000 horsemen, armed with lances and bows, waited between St. Stephen's Gate and the Gate of Jehoshafat to repulse any sortie by the Latin garrison, while the rest of his army was deployed around the siege engines.

“When Salah al-Din's forces breached the wall, the defenders tried to drive them "away with stones and molten lead, as well as with arrows and spears," but they failed. They attempted a sortie, but this too failed. Sappers in Salah al-Din's army succeeded in making a breach, about thirty metres in length, in the wall which was sapped in two days. After that, the defenders fled the walls: "In the whole city there was not found a man bold enough to dare stand guard for a single night for a 100-bezant reward."

“The breach in the wall was in the same spot from which the first Crusaders had entered the city in 1099. When the wall fell, the great cross that had been installed there to celebrate the capture of Jerusalem by the Latins in that year also fell. The author of Libellus states that he personally heard a proclamation by the patriarch and others indicating that "if 50 strong men and daring servants were found who could guard the corner that had been destroyed for that one night, they would be given all the arms they wanted, but they were not to be found."

Surrender of Jerusalem

Hadia Dajani-Shakeel wrote: “Ernoul informs us that, realizing they could not hold the city for very long, the authorities in Jerusalem held an emergency meeting, attended by the Patriarch Heraclius and Balian of Ibelin, at which they discussed their military options. The citizens' representatives and the sergeants advanced a proposal for a massive attack on Salah al-Din's forces, thus "dying honourably in defence of the city." [Source: Hadia Dajani-Shakeel. "Some Medieval Accounts of Salah al-Din's Recovery of Jerusalem (Al-Quds)", “Studia Palaestina: Studies in honour of Constantine K. Zurayk,” edited by Hisham Nashabe, Institute for Palestine Studies, Beirut 1988 ]

“The patriarch rejected this proposal, however, arguing that if all the men died, the fate of the women and children in the city would be left in the hands of the Muslim forces, who would certainly convert them to Islam. He proposed instead that the city should be surrendered, and he promised that after surrendering it, the Latins would seek help from Europe. The authorities accordingly agreed, and hence dispatched Balian to discuss the terms of the surrender with Salah al-Din. According to Ernoul, Balian left the city to negotiate with Salah al-Din, and, while the talks were in progress, the Muslim forces succeeded in raising their flag on the main wall. Rejoicing, Salah al-Din turned to Balian and asked: "Why are you proposing to surrender the city? We have already captured it!" However, the Latins counter-attacked Salah al-Din's forces, driving them away from the section they had captured. Salah al-Din was so angered by this that he dismissed Balian and told him to return the following day.

“When Balian appeared again before Salah al-Din, he asked for a general amnesty in return for the surrender of the city, but Salah al-Din rejected his request. Balian then threatened that the Latins inside the city would fight to the death: They would burn their houses, destroy the Dome of the Rock, uproot the Rock, and kill all Muslim prisoners, who were estimated to number in the thousands; they would destroy their property and kill their women and children. According to al-Qadi al-Fadil, Balian also "offered a tribute in an amount that even the most covetous could not have hoped for."

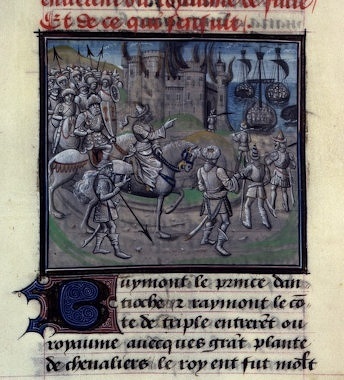

Christians in Jerusalem

“Salah al-Din met with his commanders and told them that this was an excellent opportunity to capture the city without further bloodshed. After lengthy negotiations, an agreement was reached between Salah al-Din and the Latins according to which they were granted safe conduct to leave the city, provided that each male paid a ransom of ten dinars, each female paid five dinars, and each child was ransomed for two dinars. All those who paid their ransom within forty days were allowed to leave the city, while those who could not ransom themselves were to be enslaved.

“'Imad al-Din indicates that Balian offered to pay 30,000 dinars on behalf of the poor, an offer that was accepted, and the city was at last surrendered on Friday, 27 Rajab, A.H. 583/2 October, A.D. 1187. The twenty-seventh of Rajab was the anniversary of al-Mi'raj, through which Jerusalem had become a part of Islamic history and piety . When Salah al-Din entered Jerusalem triumphantly, he immediately released the Muslim prisoners, who, according to Ibn Shaddad, numbered close to 3,ooo. The newly released captives were later rewarded with the homes vacated by the Latins.

See Separate Article: JERUSALEM AFTER IT WAS RETAKEN BY SALADIN AND THE MUSLIMS africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994). “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024