Home | Category: Assyrians / Government and Legal System

WAR AND WARFARE IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA

Akkadian Victory stelae Mesopotamians are credited by some with developing state-sponsored warfare. The kingdoms of ancient Mesopotamia and the territory they occupied in present-day Iraq were vulnerable to attacks from invaders because the Tigris and Euphrates area has few natural boundaries.

Egypt flourished under the leadership of one ruler and was relatively peaceful while Mesopotamia was often divided into several kingdoms and city-states and was racked by wars. This is partly explained by geography. Mesopotamian kingdoms were spread out between two rivers and its many tributaries, and could be easily attacked from any direction, while ancient Egypt was located primarily within one river valley and was removed from the outside world by deserts. Attacks usually only came from the northeast — and to a lesser extent in the south — which meant defenses could be concentrated there. The fact that Mesopotamia was composed of many different kingdoms and city-states that rose, dominated, declined and battled each other also explains why it was never produced a single unified tradition of culture like Egypt.

Armed conflict occurred with some regularity in Mesopotamia. Warfare tended to be a spring time activity. Horse and horse-like animals were first used in battle there. Weapons included chariots (Assyrians), swords, maces and spears made from iron and bronze, and siegecraft.

Soldiers in Assyria were required to fight in battles every third year of their compulsory military service. Herodotus wrote in 403 B.C.: “The Assyrians went to war with helmets upon their heads made of brass, and plaited in a strange fashion which is not easy to describe. They carried shields, lances, and daggers very like the Egyptian; but in addition they had wooden clubs knotted with iron, and linen corselets. This people, whom the Hellenes call Syrians, are called Assyrians by the barbarians. The Chaldeans served in their ranks, and they had for commander Otaspes, the son of Artachaeus.”

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Warfare in the Ancient World” by Brian Todd Carey , Joshua B. Allfree , et al. 2020

Amazon.com;

“On Ancient Warfare: Perspectives on Aspects of War in Antiquity 4000 BC to AD 637"

by Richard A Gabriel (2018) Amazon.com;

“Rituals of War: The Body and Violence in Mesopotamia” by Zainab Bahrani (2008)

Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Assyrians: Empire and Army, 883–612 BC” by Mark Healy (2000) Amazon.com;

“Landscapes of Warfare: Urartu and Assyria in the Ancient Middle East” by Tiffany Earley-Spadoni (2025) Amazon.com;

“The Assyrian Army I.: The Structure of the Neo-Assyrian Army as Reconstructed from the Assyrian Palace Reliefs and Cuneiform Sources / 2, Cavalry and Chariotry” by Tamás Dezső (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Assyrian Army II / II. Recruitment and Logistics

by Dezső Tamás (2016) Amazon.com;

“Religion and Ideology in Assyria” by Beate Pongratz-Leisten (2015) Amazon.com;

“Relations of Power in Early Neo-Assyrian State Ideology” by Mattias Karlsson (2016) Amazon.com;

“Royal Image and Political Thinking in the Letters of Assurbanipal (State Archives of Assyria Studies) by Sanae Ito (2024) Amazon.com;

“Grants, Decrees and Gifts of the Neo-Assyrian Period (State Archives of Assyria)

by L. Kataja and R. Whiting (1995) Amazon.com;

“Assyria: The Rise and Fall of the World's First Empire” by Eckart Frahm (2023) Amazon.com;

“Assyrian Empire: A History from Beginning to End” by History Hourly (2019) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Assyria” by Eckart Frahm (2017) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction” by Karen Radner (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Might That Was Assyria” by H. W. F. Saggs (1984) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Assyria” by James Baikie (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: an Enthralling Overview of Mesopotamian History (2022) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: a Captivating Guide (2019) Amazon.com;

“A History of the Ancient Near East” by Marc Van De Mieroop (2003) Amazon.com;

Assyrian Army

Early Bows and Arrows

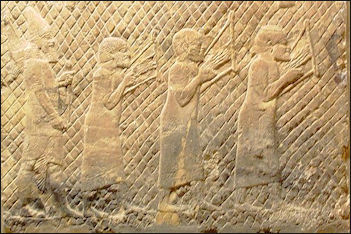

Assyrian archers The oldest indication for archery in Europe comes from the Stellmoor in the Ahrensburg valley north of Hamburg, Germany and date from the late Paleolithic about 9000-8000 BC. The arrows were made of pine and consisted of a mainshaft and a 15-20 centimetre (6-8 inches) long foreshaft with a flint point. There are no known definite earlier bows or arrows, but stone points which may have been arrowheads were made in Africa by about 60,000 years ago. By 16,000 B.C. flint points were being bound by sinews to split shafts. Fletching was being practiced, with feathers glued and bound to shafts. [Source: Wikipedia]

The first actual bow fragments are the Stellmoor bows from northern Germany. They were dated to about 8,000 B.C. but were destroyed in Hamburg during the Second World War. They were destroyed before Carbon 14 dating was invented and their age was attributed by archaeological association. [Ibid]

The second oldest bow fragments are the elm Holmegaard bows from Denmark which were dated to 6,000 B.C. In the 1940s, two bows were found in the Holmegård swamp in Denmark. The Holmegaard bows are made of elm and have flat arms and a D-shaped midsection. The center section is biconvex. The complete bow is 1.50 m (5 ft) long. Bows of Holmegaard-type were in use until the Bronze Age; the convexity of the midsection has decreased with time. High performance wooden bows are currently made following the Holmegaard design. [Ibid]

Around 3,300 B.C. Otzi was shot and killed by an arrow shot through the lung near the present-day border between Austria and Italy. Among his preserved possessions were bone and flint tipped arrows and an unfinished yew longbow 1.82 m (72 in) tall. See Otzi, the Iceman

Mesolithic pointed shafts have been found in England, Germany, Denmark, and Sweden. They were often rather long (up to 120 cm 4 ft) and made of European hazel (Corylus avellana), wayfaring tree (Viburnum lantana) and other small woody shoots. Some still have flint arrow-heads preserved; others have blunt wooden ends for hunting birds and small game. The ends show traces of fletching, which was fastened on with birch-tar. [Ibid]

Bows and arrows have been present in Egyptian culture since its predynastic origins. The "Nine Bows" symbolize the various peoples that had been ruled over by the pharaoh since Egypt was united. In the Levant, artifacts which may be arrow-shaft straighteners are known from the Natufian culture, (10,800-8,300 B.C) onwards. Classical civilizations, notably the Persians, Parthians, Indians, Koreans, Chinese, and Japanese fielded large numbers of archers in their armies. Arrows were destructive against massed formations, and the use of archers often proved decisive. The Sanskrit term for archery, dhanurveda, came to refer to martial arts in general. [Ibid]

Composite Bow

Akkadian victory stele The composite bow has been a formidable weapon for over 4,000 years. Described by the Sumerians in the third millennia B.C. and favored by steppe horsemen, the early versions of these weapons were made of slender strips of wood with elastic animal tendons glued to the outside and compressible animal horn glued on the inside. [Source: “History of Warfare” by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Tendons are strongest when they are stretched, and bone and horn are strongest when compressed. Early glues were made from boiled cattle tendons and fish skin and were applied in very precise and controlled manner; and sometimes they took a year to dry properly. [Ibid]

Advanced bows that appeared centuries after the first composite bows appeared were made of pieces of wood laminated together and steamed into a curve, then bent into a circle opposite the direction it was going to be strung. Steamed animal horn was glued onto the "back," to make it hold its position. When the bow had "cured" a great amount of strength was required to bend it back to be strung. The finished product was nearly a hundred times stronger than a bow made from a sapling. [Ibid]

Long bows, used by medieval Europeans, employed the same principles of the composite bow but used heart and sap wood instead of tendons and horn. Long bows were just as powerful as composite bows but their large size and long arrows made them impractical to use from a horse. Both weapons could easily shoot an arrow over 300 years and piece armor at 100 yards. An advantage of the composite bow is that an archer could carry many more of the smaller arrows.

Copper Age and Bronze Age Weapons

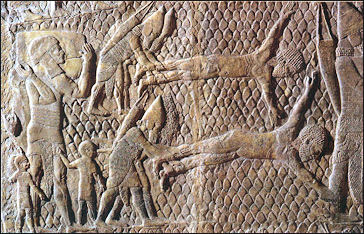

Assyrian flaying of rebels Some natural copper contains tin. During the forth millennium in present-day Turkey, Iran and Thailand man learned that these metals could be melted and fashioned into a metal — bronze — that was stronger than copper, which had limited use in warfare because copper armor was easily penetrated and copper blades dulled quickly. Bronze shared these limitations to a lesser degree, a problem that was rectified until the utilization of iron which is stronger and keeps a sharp edge better than bronze, but has a much higher melting point. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

In Copper Age Middle East Period people living primarily in what is now southern Israel fashioned axes, adzes and mace heads, from coppers. In 1993, archaeologists found a skeleton of a Copper Age warrior in a cave near Jericho. The skeleton was found in a reed mat and linen ocher-died shroud (probably woven by several people with a ground loom) along with a wooden bowl, leather sandals, a long flint blade, a walking stick and a bow with tips shaped like a ram's horns. The warrior’s leg bone showed a healed fracture.

The Bronze Age lasted from about 4,000 B.C. to 1,200 B.C. During this period everything from weapons to agricultural tools to hairpins was made with bronze (a copper-tin alloy). Weapons and tools made from bronze replaced crude implements of stone, wood, bone, and copper. Bronze knives are considerable sharper than copper ones. Bronze is much stronger than copper. It is credited with making war as we know it today possible. Bronze sword, bronze shield and bronze armored chariots gave those who had it a military advantage over those who didn't have it.

Scientists believe, the heat required to melt copper and tin into bronze was created by fires in enclosed ovens outfitted with tubes that men blew into to stoke the fire. Before the metals were placed in the fire, they were crushed with stone pestles and then mixed with arsenic to lower the melting temperature. Bronze weapons were fashioned by pouring the molten mixture (approximately three parts copper and one part tin) into stone molds.

One of the most effective weapons that was developed in Ancient Mesopotamian times was the double headed ax head which could mounted socket-fashion onto a handle.

Oldest Example of Warfare at Tell Hamoukar?

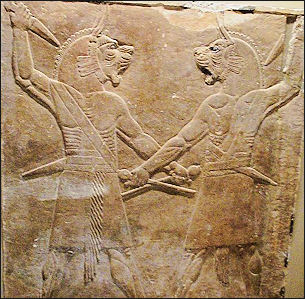

Assyrian guardian spirits The oldest known example of large scale warfare is from a fierce battle that took place at Tell Hamoukar around 3500 B.C. Evidence of intense fighting include collapsed mud walls that had undergone heavy bombardment; the presence of 1,200 oval-sapped “bullets” flung from slings and 120 large round balls. Graves held skeletons of likely battle victims. Reichel told the New York Times the clash appeared to have been a swift, rapid attack: “buildings collapse, burning out of control, burying everything in them under a vast pile of rubble.”

No one knows who the attacker of Tell Hamoukar was but circumstantial evidence points to Mesopotamia cultures to the south. The battle may have been between northern and southern Near Eastern cultures when the two cultures were relative equally, with the victory by the south giving them an edge and paving the way for them to dominate the region. Large amount of Uruk pottery was found on layers just above the battle. Reichel told the New York Times,”If the Uruk people weren’t the ones firing the sling bullets, they certainly benefitted from it. They are all over this place right after its destruction.”

Discoveries at Tell Hamoukar have changed thinking about the evolution of civilization in Mesopotamia. It was previously though that civilization developed in Sumerian cities like Ur and Uruk and radiated outward in the form of trade, conquest and colonization. But findings in Tell Hamoukar show that many indicators of civilization were present in northern places like Tell Hamoukar as well as in Mesopotamia and around 4000 B.C. to 3000 B.C. the two placed were pretty equal.

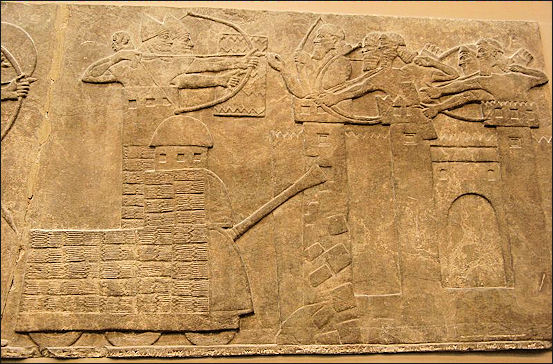

Early Defenses

Much is made about medieval castles as a defensive vehicle, but the technoloy they utilized — the moat, the fortress wall and observation towers — have been around since Jericho was established in 7000 BC. The ancient Mesopotamians and Egyptians used siege devises — battering rams, scaling ladders, siege towers, mineshafts) between 2500 and 2000 BC. Some of the battering rams were mounted on wheels and had roofs to shield soldiers from arrows. The difference between siege towers and scaling ladders in that former resembled a protected staircase; mineshafts were built under walls to undermine their foundation and makes the wall collapse. There were also siege ramps and siege engines. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Assyrian prisoners Fortress were usually made with the materials at the hand. The walled city of Catalhoyuk Hakat (7500 B.C). in Turkey and early Chinese fortresses were made of packed earth. The main purpose of a moat was not to stop attackers from climbing the wall but rather to keep them collapsing the base of the wall by mining underneath it.

Pre-Biblical Jericho had an elaborate system of walls, towers and moats in 7,500 B.C. The circular wall that surrounded the settlement had a circumference of 700 feet and was10-feet-thick and 13-feet-high. The wall in turn was surrounded by 30-foot-wide, 10-foot-deep moat. Thirty-foot-high stone observation tower required thousands of man hours to build. The technology used to build them was virtually the same as those used in medieval castles. The original walls of Jericho appear to have been built for flood control rather defensive purposes. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

The Greeks introduced catapults in the forth century BC. These primitive projectile throwers hurled stones and other object with torsion springs or counterweight (that operated a bit like a fat kid on one end of seesaw hurling another kid into the air). Catapults were generally ineffective as fortress breaking device because they were difficult to aim and didn't launch objects with much force. After gunpowder was introduced, cannons could blast walls in a particular place and the cannon balls traveled with a flat powerful trajectory. [Ibid]

Seizing a fortress was difficult. An army of hundreds inside a castle or strongholds could easily hold off thousands of attackers. The main assault strategy was to attack with a large number of men, hoping to spread the defenses thin and take advantage of a weak point. This strategy rarely worked and usually ended with a massive amount of casualties for the attackers. The most effective means of seizing a castle was bribing somebody on the inside to let you in, exploiting a forgotten latrine tunnel, making a surprise attack or setting up a position outside the castle and starving the defenders out. Most castles had huge stores of food (enough to last several hundred men at least a year) and often it was the attackers who ran out of food first. [Ibid]

Castles could be built relatively quickly. As time went on, fortification advances including the construction of inner and outer walls; towers outside the walls which gave defenders more positions to shoot from; maintain strongholds built outside the walls to defend vulnerable points like gates; elevated fighting platforms behind the walls which defenders could fire weapons from; battlements which were sort of like shields above walls. Advanced artillery fortifications of the 16th to 18th century had multi-level moats to trap attackers if they attempted to scale the walls, plus they were shaped like snowflakes or stars which gave the defenders all shorts of angles to shoot at their attackers. [Ibid]

Sumerian Warfare

There was virtually no evidence of warmaking in the early years of Sumer. Between 3100 B.C. and 2300 B.C. warfare started to play a bigger role in city-state relations as priest-kings were replaced by warlords with armies armed with lance and shields. Military tactics were developed, weapons started utilizing metals and the first "battles" begun taking place.

There is evidence that the king of Uruk went on military campaigns to bring back cedar wood from the mountains as early as early as 2700 B.C. and by 2284 B.C. Sumerian kings were fighting wars with neighboring cities and peoples like the Semites. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

The earliest evidence of state-sponsored warfare is an inscribed stele, dated to 2500 B.C., found at Lagash (also known as Telloh or Ginsu). It described a conflict between Lagash and Umma for irrigation rights and was settled in a battle in which war wagons were used. The Standard of Ur, a Sumerian object dated to around 2500 B.C. included images of warfare with wheeled vehicles and warriors. The vehicles looked more like transport vehicles than a fighting ones.

Standard of Ur for War

Sumerian Warfare Tactics, Prisoners and Spies

Around 2500 B.C. soldiers started wearing metal helmets and organizing themselves into columns with a six man front. They wore cloaks and tunics that appeared to be strengthened with metal, and used four-wheeled carts driven by four horses (prototypes of armor and chariots). The even employed "death pits" in which enemies where lured into battlefield equivalents of holes with trapdoors where they picked off like proverbial sitting ducks. [Source: “History of Warfare” by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

The primary weapons were lances and shields. By the middle of the second millennium the Sumerians had developed the sophisticated composite bow and utilized method of siege craft (breaching and scaling) to attack fortresses. The results could sometimes be quite bloody. A 4500-year-old inscription from Lagash describes piles of bodies with as many as a thousand enemy corpses. The Mesopotamians also used psychological warfare to defeat their enemies. [Ibid]

Prisoners of war were not used as slaves but were deported to differents part of the kingdom. Sometimes they were sacrificed in temples. It seems only men were killed in battles and sieges and in sacrificial rites not women or children. Historian Ignace Gelb has argued that this was so because it was "relatively easy to exert control over foreign women and children" and "the state apparatus was still not strong enough to control masses of unruly male captives." As the power of the state increased males prisoners were "marked and branded" and "freed and resettled" or used as mercenaries or bodyguards to the king.

Spies were called scouts, or eyes. They were often employed to check out what was going on in rival kingdoms. The following is an Akkadian text from one "brother" king to another, complaining he had released the scouts according to a deal that was made but had not been paid the ransom as promised: "To Til-abnu: thus says Jakun-Asar your "brother” previously about the scout's release you wrote to me. As for the scouts which came in my power I have released. That I have indeed released (them) you know, still you have not sent the money for ransom. Every since I began releasing your scouts, you have consistently not provided the money for ransom. I here — and you there — should (both) release!"

Assyrian Warfare

For the Assyrians war was almost a business and they profited mightily from the rewards of conquest. The Assyrians began using iron weapons and armor in Mesopotamia around 1200 B.C. (After the Hittites but before the Egyptians) with deadly results. The also effectively employed war chariots. They were not the first to do this but they were the first to organize them into a cavalry.

The Assyrians established the largest army up to that time in the Mediterranean. Their armies had professional soldiers, infantry, charioteers, mounted archers, fast horses, engineers and wagoners. The most important unit was the royal bodyguard, perhaps the first regular army. The other units were amassed as need arose. In battles the Assyrians used bows, slings, iron swords and lances, battering rams, oil firebombs, but relied on iron javelins.

The Assyrians according to some scholars possessed the first long-range armies. They utilized supply depots, a sophisticated road network, transport columns, and bridging trains to campaigns as far away as 300 miles from their home base and moved as rapidly as armies during World War I (30 miles a day). To get across rivers they used boats made from inflated animals skins, and, while campaigning, they carried few supplies, living instead off of food captured in enemy territory. Artwork depicts Assyrian soldiers destroying buildings with pickaxes and crowbars and then, carrying off booty. [Source: “History of Warfare” by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Towns that refused to pay tribute were sacked. According to one tablet one town was “crushed like a clay pot” and the population and leaders were made prisoners “like a herd of sheep” as the Assyrian army carried away booty.

Assyrian Attack on a Town

See Separate Article: ASSYRIAN MILITARY: CAMPAIGNS, WEAPONS, PERSONNEL africame.factsanddetails.com

Standard of Ur, War

Hammurabi's Code of Laws: 26-39: Chieftains, Soldiers

The Babylonian king Hammurabi (1792-1750 B.C.) is credited with producing the Code of Hammurabi, the oldest surviving set of laws. Recognized for putting eye for an eye justice into writing and remarkable for its depth and judiciousness, it consists of 282 case laws with legal procedures and penalties. Many of the laws had been around before the code was etched in the eight-foot-highin black diorite stone that bears them. Hammurabi codified them into a fixed and standardized set of laws. [Source: Translated by L. W. King]

If a chieftain or a man (common soldier), who has been ordered to go upon the king's highway for war does not go, but hires a mercenary, if he withholds the compensation, then shall this officer or man be put to death, and he who represented him shall take possession of his house.

If a chieftain or man be caught in the misfortune of the king (captured in battle), and if his fields and garden be given to another and he take possession, if he return and reaches his place, his field and garden shall be returned to him, he shall take it over again.

If a chieftain or a man be caught in the misfortune of a king, if his son is able to enter into possession, then the field and garden shall be given to him, he shall take over the fee of his father.

If his son is still young, and can not take possession, a third of the field and garden shall be given to his mother, and she shall bring him up.

If a chieftain or a man leave his house, garden, and field and hires it out, and some one else takes possession of his house, garden, and field and uses it for three years: if the first owner return and claims his house, garden, and field, it shall not be given to him, but he who has taken possession of it and used it shall continue to use it.

If he hire it out for one year and then return, the house, garden, and field shall be given back to him, and he shall take it over again.

If a chieftain or a man is captured on the "Way of the King" (in war), and a merchant buy him free, and bring him back to his place; if he have the means in his house to buy his freedom, he shall buy himself free: if he have nothing in his house with which to buy himself free, he shall be bought free by the temple of his community; if there be nothing in the temple with which to buy him free, the court shall buy his freedom. His field, garden, and house shall not be given for the purchase of his freedom.

If a . . . or a . . . enter himself as withdrawn from the "Way of the King," and send a mercenary as substitute, but withdraw him, then the . . . or . . . shall be put to death.

If a . . . or a . . . harm the property of a captain, injure the captain, or take away from the captain a gift presented to him by the king, then the . . . or . . . shall be put to death.

If any one buy the cattle or sheep which the king has given to chieftains from him, he loses his money.

The field, garden, and house of a chieftain, of a man, or of one subject to quit-rent, can not be sold.

If any one buy the field, garden, and house of a chieftain, man, or one subject to quit-rent, his contract tablet of sale shall be broken (declared invalid) and he loses his money. The field, garden, and house return to their owners.

A chieftain, man, or one subject to quit-rent can not assign his tenure of field, house, and garden to his wife or daughter, nor can he assign it for a debt.

Standard of Ur, War

He may, however, assign a field, garden, or house which he has bought, and holds as property, to his wife or daughter or give it for debt.

If a man is taken prisoner in war, and there is a sustenance in his house, but his wife leave house and court, and go to another house: because this wife did not keep her court, and went to another house, she shall be judicially condemned and thrown into the water. [Source: Translated by L. W. King]

If any one be captured in war and there is not sustenance in his house, if then his wife go to another house this woman shall be held blameless.

If a man be taken prisoner in war and there be no sustenance in his house and his wife go to another house and bear children; and if later her husband return and come to his home: then this wife shall return to her husband, but the children follow their father.

Mesopotamia Less Violent That Other Places?

Violence appears to be less widespread in Mesopotamia than in the rest of the Near East 5,200 years ago skeletal remains suggest. Léa Surugue wrote in the International Business Times: “Between 5,200 and 2,500 years ago, violence was probably less widespread in Mesopotamia than in neighbouring regions, a study has revealed. Ancient craniums from the region bear little signs of trauma compared to those found in the Levant or in Anatolia. A potential explanation is that the early emergence of state structures may have prevented outbreaks of violence between the inhabitants of Mesopotamia. [Source: Léa Surugue, International Business Times, April 4, 2017 -]

“At many archaeological sites around the world, evidence of violence can be observed first hand on skeletal remains. While some indicators of violence are quite ambiguous (such as fractures of the arm bones), other signs are a clear testimony of deadly conflict between humans (projectiles embedded in the bones). Another good proxy for violence is the presence of cranial lesions on skeletons, as these injuries can be the results of accidents but are more often attributed to interpersonal violence in the context of war. -

“Surprisingly, evidence for cranial trauma during the Bronze Age and the Iron Age is sparse in Mesopotamia compared to other regions, even though many human remains have been uncovered there in the last two decades. "I have been active as an archaeologist in Mesopotamia for 20 years, and I was struck by the fact that there was a very low frequency of cranial trauma on the remains that I examined. I decided to investigate and see what had been discovered previously on the subject", archaeologist Arkadiusz Soltysiak told IBTimes UK. -

“Soltysiak, a researcher at the University of Warsaw (Poland) who published his findings in the Journal of Osteoarchaeology Literature Review, conducted a review of the available scientific literature on the topic (both published and unpublished), thus gathering cranial trauma data from 25 archaeological sites located in Mesopotamia. Craniums from 1,278 individuals, spanning a long period from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic to modern times (from about 8700 B.C. to 1500 CE), were analysed in these papers. Soltysiak's review of the data confirmed what he had observed previously – the frequency of cranial trauma was low in Mesopotamia, standing at 2.2 percent. This may sound a little puzzling. Historical sources from Mesopotamia feature many records of bloody military conflicts and there is a lot of evidence available for large military actions taking place in the region at least since the mid-third millennium B.C.. A higher frequency of violence-related injuries would therefore be expected. -

“But Soltysiak points out that men and women were similarly affected by cranial trauma and sharp-force trauma and evidence for injuries made with swords or axes was rare. These injuries were probably the result of accidents or small-scale conflicts between individuals rather than warfare. There also seems to be a decline in cranial trauma from the Neolithic to later periods, suggesting a general decrease in the rate of violence in the Bronze Age and in the Iron Age. -

“The archaeologist believes that the early formation of state-like structures in Mesopotamia may explain both why violence declined when it did and why it was less widespread than in other regions. "In the Levant and in Anatolia, states were created much later and the central authority was not as strong as in Mesopotamia. The early emergence of state-structures and the establishment of professional armies in Mesopotamia meant that most farmers and city dwellers became less involved in violent conflicts from the early Bronze Age. It helps explain why levels of violence at the time were low compared with other parts of the Near East", he said.” -

Evidence of PTSD in Ancient Assyria

Ancient warriors in Assyria could have suffered from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) as far back as 1300 B.C. researchers at Anglia Ruskin University say. It had been previously thought that the first record of PTSD was in 490 B.C., during the Greco-Persian Battle of Marathon. Texts from the period refer to how King Elam’s mind “changed”, meaning that he was disturbed, or suffering from PTSD.Soldiers in Assyria were required to fight in battles every third year of their compulsory military service and this is believed to be the cause of the condition. [Source:Ben Tufft, The Independent, January 25, 2015 ^|^]

Ben Tufft wrote in The Independent: “The paper states that while modern technology has increased the effectiveness and types of weaponry, "ancient soldiers facing the risk of injury and death must have been just as terrified of hardened and sharpened swords, showers of sling-stones or iron-hardened tips of arrows and fire arrows." It added: "The risk of death and the witnessing of the death of fellow soldiers appears to have been a major source of psychological trauma. "Moreover, the chance of death from injuries, which can nowadays be surgically treated, must have been much greater in those days. All these factors contributed to post-traumatic or other psychiatric stress disorders resulting from the experience on the ancient battlefield." ^|^

Standard of Ur, War

“Professor Jamie Hacker Hughes, director of the Veterans and Families Institute at the university and co-author of the paper, said that the research shows that PTSD was first witnessed far earlier than previously thought. “This paper, and the research on which it is based, demonstrates that post traumatic psychological symptoms of battle were evident in ancient Mesopotamia. Well before the Greek and Roman eras, before the time of Abraham and the biblical Kings, David and Solomon, and contemporarily with the time of the Pharaohs,” he said. "Especially significant is that this evidence comes from the area known as the cradle of civilisation and, of course, the site of much recent conflict including the recent Gulf and Iraq Wars in which many British service personnel were involved." The paper is entitled “Nothing New Under the Sun: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders in the Ancient World” and was co-authored with Dr Walid Abdul-Hamid of Queen Mary University of London.” ^|^

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024