Home | Category: Abbasids / Abbasids

CALIPH AL-MA'MUN

Abu al-Abbas Abd Allah ibn Harun al-Rashid 786/9– 833), better known by his regnal name al-Ma'mun, was the seventh Abbasid caliph, reigning from 813 until his death in 833. He succeeded his half-brother al-Amin after a civil war, during which the unity of the Abbasid Caliphate was weakened by rebellions and the rise of local warlords. Much of al-Ma'mun’s domestic rule was taken by pacification campaigns. Well educated and deeply interested in scholarship, al-Ma'mun promoted the Translation Movement, the flowering of learning and the sciences in Baghdad, and the publishing of al-Khwarizmi's book now known as "Algebra". He is also known for supporting the Islamic theological doctrine of Mu'tazilism and for imprisoning Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal, the rise of religious persecution. Under his rule the Abbasids resumed large-scale warfare with the Byzantine Empire.. [Source: Wikipedia]

Abul Hasan Ali Al-Masu'di wrote: “When Haroun Al Rashid died he left the empire to his sons Emin and Ma’mun, giving the former Iraq and Syria, and the latter Khorassan and Persia. Emin had the title of Caliph, to which Ma’mun was to succeed. War broke out between the brothers; Emin fled from Baghdad, but was captured and slain, and his head sent to Ma’mun in Khorassan, who wept at the sight of it. He had, however, previously, when his general Tahir sent to him requesting to know what to do with Emin in case he caught him, sent to the general a shirt with no opening in it for the head. By this Tahir knew that he wished Emin to be put to death, and acted accordingly. [Source: The Book of Golden Meadows, c. 940 CE , Charles F. Horne, ed., “The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East,” (New York: Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb, 1917), Vol. VI: Medieval Arabia, pp. 35-89, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

“The Caliph, however, bore a grudge against Tahir for the death of his brother, as was shown by the following circumstance: Tahir went one day to ask some favor from Al Ma’mun; the latter granted it, and then wept till his eyes were bathed in tears. "Commander of the Faithful," said Tahir, "why do you weep? May God never cause you to shed a tear! The universe obeys you, and you have obtained your utmost wishes." "I weep not," replied the Caliph, "from any humiliation which may have befallen me, neither do I weep from grief, but my mind is never free from cares."

“These words gave great uneasiness to Tahir, and, on retiring, he said to Husain, the eunuch who waited at the door of the Caliph's private apartment: "I wish you to ask the Commander of the Faithful why he wept on seeing me." On reaching home Tahir sent Husain one hundred thousand dirhems. Some time afterward, when Al Ma’mun was alone and in a good humor, Husain said to him: "Why did you weep when Tahir came to see you?" "What is that to you?" replied the Prince. "It made me sad to see you weep," answered the eunuch. "I shall tell you the reason," the Caliph said; "but if you ever allow it to pass your lips, I shall have your head taken off." "O my master," the eunuch replied, "did I ever disclose any of your secrets?" "I was thinking of my brother Emin," said the Caliph, "and of the misfortune which befell him, so that I was nearly choked with weeping; but Tahir shall not escape me! I shall make him feel what he will not like."

“Husain related this to Tahir, who immediately rode off to the Vizier Abi Khalid, and said to him: "I am not parsimonious in my gratitude, and a service rendered to me is never lost; contrive to have me removed away from Al Ma’mun." "I shall," replied Abi Khalid. "Come to me tomorrow morning." He then rode off to Al Ma’mun, and said "I was not able to sleep last night." "Why so?" asked the Caliph. "Because you have entrusted Ghassan with the government of Khorassan, and his friends are very few, and I fear that ruin awaits him." "And whom do you think a proper person for it?" said Al Ma’mun. "Tahir," replied Abi Khalid. "He is ambitious," observed the Caliph. "I will answer for his conduct," said the other.

Websites on Islamic History: History of Islam: An encyclopedia of Islamic history historyofislam.com ; Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World oxfordislamicstudies.com ; Sacred Footsetps sacredfootsteps.com ; Islamic History Resources uga.edu/islam/history ; Internet Islamic History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall/islam/islamsbook ; Islamic History friesian.com/islam ; Muslim Heritage muslimheritage.com ; Chronological history of Islam barkati.net

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Great Caliphs: The Golden Age of the 'Abbasid Empire” by Amira K. Bennison Amazon.com ;

“The Abbasid Caliphate” by Tayeb El-Hibri Amazon.com ;

“Caliphate: The History of an Idea” by Hugh Kennedy Amazon.com ;

“Baghdad During the Abbasid Caliphate” by G Le Strange Amazon.com ;

“The House of Wisdom: How Arabic Science Saved Ancient Knowledge and Gave Us the Renaissance” by Jim Al-Khalili, Simon Vance, et al. Amazon.com ;

“1001 Inventions: The Enduring Legacy of Muslim Civilization: Official Companion to the 1001 Inventions Exhibition” by Salim T.S. Al-Hassani Amazon.com ;

“Pathfinders: The Golden Age Of Arabic Science” by Jim Al-Khalili Amazon.com ;

“The Arabs: A History” by Eugene Rogan Amazon.com ;

“The New Cambridge History of Islam: Volume 1, Formation of the Islamic World, 6th to 11th Centuries Amazon.com ;

“Arabs: A 3,000-Year History of Peoples, Tribes, and Empires” by Tim Mackintosh-Smith, Ralph Lister, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Arabs in History” by Bernard Lewis Amazon.com ;

“History of Islam” (3 Volumes) by Akbar Shah Najeebabadi and Abdul Rahman Abdullah Amazon.com

Mamun and the Intellectual Blossoming of the Islamic World

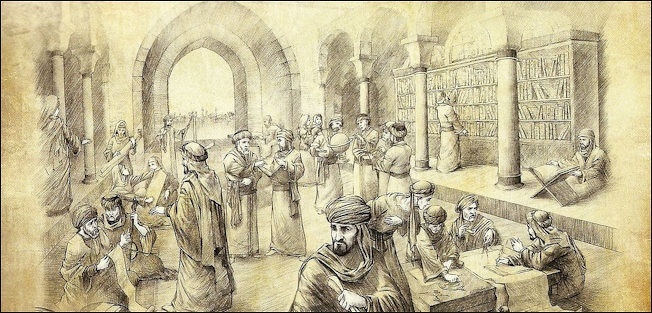

Mamun was the caliph who was largely responsible for cultural expansion. An Arab historian states the following: "He looked for knowledge where it was evident, and thanks to the breadth of his conceptions and the power of his intelligence, he drew it from places where it was hidden. He entered into relations with the emperors of Byzantium, gave them rich gifts, and asked them to give him books of philosophy which they had in their possession. These emperors sent him those works of Plato, Aristotle, Hippocrates, Galen, Euclid, and Ptolemy which they had. Mamun then chose the most experienced translators and commissioned them to translate these works to the best of their ability.” [Source: Gaston Wiet, “Baghdad: Metropolis of the Abbasid Caliphate,” Chapter 5: the Golden Age the Golden Age of Arab and Islamic Culture translated by Feiler Seymour University of Oklahoma Press, 1971]

After the translating was done as perfectly as possible, the caliph urged his subjects to read the translations and encouraged tbem to study them. Consequently, the scientific movement became stronger under this prince's reign. Scholars held high rank, and the caliph surrounded himself with learned men, legal experts, traditionalists, rationalist theologians, lexicographers, annalists, metricians, and genealogists. He then ordered instruments to be manufactured."

Gaston Wiet wrote in “Baghdad: Metropolis of the Abbasid Caliphate": ““The caliph Mamun was responsible for the translation of Greek works into Arabic. He founded in Baghdad the Academy of Wisdom, which took over from the Persian university of Jundaisapur and soon became an active scientific center. The Academy's large library was enriched by the translations that had been undertaken. Scholars of all races and religions were invited to work there. They were concerned with preserving a universal heritage, which was not specifically Moslem and was Arabic only in language. The sovereign had the best qualified specialists of the time come to the capital from all parts of his empire. There was no lack of talented men. The rush toward Baghdad was as impressive as the horsemen's sweep through entire lands during the Arab conquest. The intellectuals of Baghdad eagerly set to work to discover the thoughts of antiquity.

Al Ma’mun Kills Tahir

Abul Hasan Ali Al-Masu'di wrote: “Al Ma’mun then sent for Tahir, and named him governor of Khorassan on the spot; he made him also a present of an eunuch, to whom he had just given orders to poison his new master if he remarked anything suspicious in his conduct. When Tahir was solidly established in his government he ceased mentioning Al Ma’mun's name in the public prayers as the reigning Caliph. A dispatch was immediately sent off by express to inform Al Ma’mun of the circumstance, and the next morning Tahir was found dead in his bed. It is said that the eunuch administered the poison to him in some sauce. [Source: The Book of Golden Meadows, c. 940 CE , Charles F. Horne, ed., “The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East,” (New York: Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb, 1917), Vol. VI: Medieval Arabia, pp. 35-89, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

House of Wisdom

“Al Ma’mun placed his two sons under the tuition of Al Farra, so that they might be instructed in grammar. One day Al Farra rose to leave the house, and the two young princes hastened to bring his shoes. They struggled between themselves for the honor of offering them to him, and they finally agreed that each of them should present him with one slipper. As Al Ma’mun had secret agents who informed him of everything that passed, he learned what had taken place, and caused Al Farra to be brought before him.

“When he entered, the Caliph said to him: "Who is the most honored of men?" Al Farra answered: "I know not any one more honored than the Commander of the Faithful." "Nay," replied Al Ma’mun, "it is he who arose to go out, and the two designated successors of the Commander of the Faithful contended for the honor of presenting him his slippers, and at length agreed that each of them should offer him one."

“Al Farra answered: "Commander of the Faithful, I should have prevented them from doing so had I not been apprehensive of discouraging their minds in the pursuit of that excellence to which they ardently aspire. We know by tradition that Ibn Abbas held the stirrups of Hasan and Husain, when they were getting on horseback after paying him a visit. One of those who were present said to him: 'How is it that you hold the stirrups of these striplings, you who are their elder?' To which he replied: 'Ignorant man! No one can appreciate the merit of people of merit except a man of merit.'"

“Al Ma’mun then said to him: "Had you prevented them, I should have declared you in fault. That which they have done is no debasement of their dignity; on the contrary, it exalts their merit. No man, though great in rank, can be dispensed from three obligations: he must respect his sovereign, venerate his father, and honor his preceptor. As a reward for their conduct, I bestow upon them twenty thousand dinars, and on you for the good education you give them, ten thousand dirhems."

“When Al Ma’mun was still in Khorassan, a revolt was raised against him in Baghdad by his uncle, Ibrahim, the son of Mahdi. This prince had great talent as a singer, and was a skilful performer on musical instruments. Being of a dark complexion, which he inherited from his mother, Shikla, who was a negress, and of a large frame of body, he received the name of al-Tinnin (the Dragon). He was proclaimed Caliph at Baghdad during the absence of Al Ma’mun. The cause which led the people to renounce Al Ma’mun and choose Ibrahim was that the former had chosen as his successor one of the descendants of ali, and in doing so had ordered the public to cease wearing black, which was the distinctive color of the Abbassides, the reigning family, and to put on green, the color of the family of ali and their partisans.

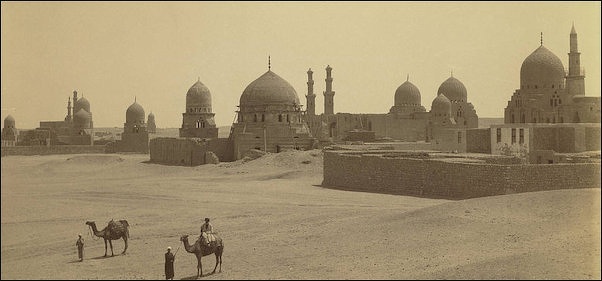

Abbasid Caliphs, Egypt

Ibrahim, the Outcast

Abul Hasan Ali Al-Masu'di wrote: “On Ma’mun's entry into Bagdad, Ibrahim fled disguised as a woman. He was, however, detected and arrested by one of the negro police. When he was before Al Ma’mun, who addressed him in ironic terms, he replied: "Prince of the believers, my crime gives you the right of retaliation, but forgiveness is near neighbor to piety. God has placed you above all those who are generous, as he has placed me above all criminals in the magnitude of my crime. If you punish me you will be just; if you pardon me you will be great." "Then I pardon you," said Ma’mun, and prostrated himself in prayer. [Source: The Book of Golden Meadows, c. 940 CE , Charles F. Horne, ed., “The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East,” (New York: Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb, 1917), Vol. VI: Medieval Arabia, pp. 35-89, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

“He commanded, however, that Ibrahim should continue to wear the burqa, or long female veil in which he had fled, so that people might see in what disguise he had been arrested; he ordered also that he should be exposed to view in the palace courtyard; then he committed him to police supervision, and finally, after some days of detention, set him free.

“The following anecdote was related by Ibrahim regarding the time when he was in hiding with a price set on his head: "I went out one day at the hour of noon without knowing whither I was going. I found myself in a narrow street, which ended in a cul-de-sac, and noticed a negro standing in front of the door of a house. I went straight to him, and asked if he could afford me shelter for a short time. He consented, and bade me enter. The hall was adorned with mats and leather cushions. Then he left me alone, closed the door, and departed. A suspicion flashed across my mind; this man knew that a price was set on my head, and had gone to denounce me.

“"While I was revolving these gloomy thoughts, he returned with a servant bearing a tray loaded with victuals. 'May my life be a sacrifice for you,' he said. 'I am a barber, and therefore I have not touched any of these things with my hand; do me the honor to partake of them.' Hunger pressed me; I rose and obeyed. 'What about some wine?' he asked. 'I do not detest it,' I replied. He brought some, and then said again: 'May my life be your ransom! Will you allow me to sit near you and drink to your health?' I consented. After having emptied three cups, he opened a cupboard and took out a lute. 'Sir,' he said, 'it does not behoove a man of my low degree to beg you to sing, but your kindness prompts me to do so; if you deign to consent it will be a great honor for your slave.'

Baghdad

“"'How do you know that I am a good singer?' I asked him. 'By allah!' he answered, with an air of astonishment, 'your reputation is too great for me not to know it: you are Ibrahim, the son of Mahdi, and a reward of a hundred thousand dirhems is promised by Al Ma’mun to the man who will find you.' At these words I took the lute, and was about to commence, when he added: 'Sir, would you be so kind as first to sing the piece which I shall choose?' When I consented he chose three airs in which I had no rival. Then I said to him: 'You know me, I admit; but where did you learn to know these three airs?' 'I have been,' he answered, 'in the service of Ishak, son of Ibrahim Mausili, and I have often heard him speak of the great singers and the airs in which they excelled; but who could have guessed that I would hear you myself and in my own house?'

“"I sang to him accordingly, and remained some time in his company, charmed with his agreeable manners. At nightfall I took leave of him. I had brought with me a purse full of gold pieces; I offered it to him, promising him a greater reward some day. 'This is strange,' he said; 'it is rather I who should offer you all I possess, and implore you to do me the honor to accept it. Only respect has restrained me from doing so.' He refused, accordingly, to receive anything from me; but he went out with me and put me on the road to the place whither I wished to go. Then he went off, and I have never seen him since."

Al Ma’mun and the Manicheans

Abul Hasan Ali Al-Masu'di wrote: “One day ten inhabitants of Basra were denounced to Al Ma’mun as heretics who held the doctrine of Manes (Manicheans) and the two principles of light and darkness. He ordered them to be brought into his presence. A parasite, who saw them being taken, said to himself: "Here are folk who are going off for a jollification." He slipped in among them, and accompanied them without perceiving who they were till they reached the boat in which their guards made them embark. "Doubtless this is a pleasure party!" he exclaimed, and went on board with them. Soon, however, the guards brought chains and fettered the whole band, including the parasite, who said to himself: "My greediness has ended by making me a prisoner." Then he addressed the seniors of the band: "Pardon me," he said; "may I ask who you are?" "Tell us, rather, who you are," they answered, "and whether we may reckon you among our brothers." "God knows I scarcely know you," he replied. "As for me, to tell the truth, I am a professional parasite. When I left my home this morning I happened to fall in with you. Struck with your agreeable appearance and good manners, I said to myself: 'Here are some well-to-do people going to enjoy themselves.' Consequently I joined your company, and took my place beside you as though I were one of you. When we reached the boat, which was provided with carpets and cushions, and I saw all these bags and well-filled baskets, I thought: 'They are going for an outing in some park or pleasure-ground; this is a lucky day for me.' [Source: The Book of Golden Meadows, c. 940 CE , Charles F. Horne, ed., “The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East,” (New York: Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb, 1917), Vol. VI: Medieval Arabia, pp. 35-89, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

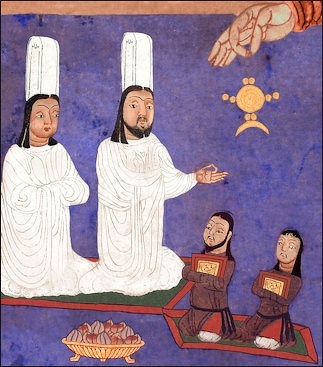

“"I was still congratulating myself when the guards came and fettered you, and me with you. I now feel quite bewildered; tell me, therefore, what it is all about." These words amused the prisoners, and made them smile. They replied: "Now that you are on the list of the suspected, and are chained, know that we are Manichaeans who have been denounced to Ma’mun, and are being taken to him. He will ask us who we are, will question us concerning our belief, and will exhort us to repent and to abjure our religion, proposing various tests to us; he will, for example, show us an image of Manes, commanding us to spit upon it and to renounce him; he will command us to sacrifice a pheasant. Whoever will do so will save his life; whoever refuses will be put to death. When you are called and put to the test you will say who you are and what your belief is, according as you feel prompted. But did you not say you were a parasite? Now, such people have an ample store of anecdotes and stories; shorten our journey, then, by recounting some."

Manicheans

“As soon as they arrived at Baghdad the prisoners were conducted into the presence of Ma’mun. He called each in turn as his name was on the list; he asked each concerning his sect, and urged them to renounce Manes, showing them his image, and commanding them to spit on it. As they refused, he had them handed over one by one to the executioner.

“At last the parasite's turn came. But as the ten prisoners had been done with and the list was exhausted, Ma’mun asked the guards who he was. "Truly, we know nothing about him," they answered. "We found him among them and brought him hither." "Who are you?" the Caliph asked him. "Prince of the believers," he said, "may my wife be divorced if I understand what they are talking about! I am only a poor parasite." And he told him his whole story from beginning to end.

“The Caliph was much amused, and ordered the image of Manes to be presented to him; the parasite cursed and renounced the heretic heartily. Al Ma’mun, however, was about to punish him for his temerity and impudence, when Ibrahim, the son of Mahdi, who was present, said: "Sire, let this man off, and I will relate to you a kind of adventure, of which I was the hero." The Caliph assented, and Ibrahim continued: "Prince of the believers, I had gone out one day, and was roving at random through the streets of Baghdad, when I came to the porch of a lofty mansion, whence issued a delicious odor of spices and dressed meats, by which I was strongly attracted. I addressed a passer-by, and asked to whom the house belonged. 'To a linen-merchant,' he answered. 'What is his name?' I asked. 'Such a one, son of such a one,' was his reply. I lifted my eyes to the house. Through the lattice-work which covered one of the windows I saw appear such a beautiful hand and wrist as I had never seen before. The charm of this apparition made me forget the enticing odors, and I stood there troubled and perplexed. Finally, I asked the man, who had remained standing near if the master of the house ever gave entertainments. 'Yes, I think he is giving one today,' he answered; 'but his guests are merchants, staid and sober people like himself.'

“"We were thus engaged in talk when two persons of well-to-do appearance came down the street toward us. 'There are his two guests,' the man said to me. 'What are their names and their fathers' names?' I asked. He informed me, and I accosted them immediately, saying: 'May my life be your sacrifice; your host is waiting impatiently for you.' I escorted them to the door as if I belonged to the house; they went in, and I followed. The master of the house perceived me, and, supposing that I had been brought by his friends, received me graciously, and placed me in the seat of honor. Then the meal was brought; it was well served, and we did honor to the dishes, whose savor excelled their odor. When the food had been removed and we had washed our hands, our host led us into another hall richly adorned. He redoubled his politeness toward me, and specially addressed his conversation to me. The two guests believed me to be an intimate friend of his, while the host treated me in this fashion because he believed I had been brought by his two friends.

“"We had already emptied several cups when a young female slave came forward, as graceful as a willow-branch, and saluted us without timidity. She was offered a cushion to sit upon, and a lute was brought to her, which she tuned with a skill which struck me. She then sang an air in a most enchanting fashion; so great was the skill and art with which she sang that I could not suppress a feeling of jealousy. 'Young girl,' I said to her, 'you have still a good deal to learn.' These words irritated her; she threw down the lute, and exclaimed to the host: 'Since when do you admit to your intimacy such vexatious guests?'

Manicheans

“"I repented of my remark when I saw the others look at me askance. 'Is there a lute here?' I asked. 'Yes,' was the reply. They brought me one, which I tuned to my liking, and then sang. I had hardly finished when the young slave cast herself at my feet, and, embracing them, said: 'Sir, pardon me in the name of heaven; I have never heard that air sung so exquisitely.' Her master and those present followed her example in praising me; cheerfulness was restored, and the cups circulated rapidly. I sang again, and the enthusiasm of my hearers was roused to such a pitch that I thought they would take leave of their senses. I waited awhile to let them recover themselves; then, taking my lute again, I sang for the third time. 'By allah!' cried the slave, 'that is what deserves to be called singing!'

“"The others, however, were beginning to feel the effects of the wine; the master of the house, who had a stronger head than his guests, entrusted them to the care of his own servants and of theirs, and had them conveyed home. I remained alone with him. After we had emptied some more cups, he said to me: 'Truly, sir, I consider the past days of my life, in which I did not know you, wasted. Kindly inform me who you are.' He pressed me so much that at last I told him my name. Immediately he rose, kissed my hand, and said: 'I should have been surprised, sir, had any one of a rank inferior to your own possessed such skill. To think one of the royal house was with me all the time, and I knew it not!' Being pressed by him to tell my story and what had attracted me to his house, I told him how I had stopped when I smelt the odor of the food, and described the hand and wrist I had seen at the window.

“"He straightway called one of his female slaves and said: 'Go and tell So-and-so to come down.' He had all the slaves in succession brought before me. After having examined their hands, I said: 'No! the possessor of the hand I saw is not among them.' 'By allah!' said my host, 'there are only my mother and my sister left! I will send for them.' Such generosity and kindness of heart surprised me. I said to him: 'May my life be your sacrifice! Before calling your mother, call your sister; it is probably she of whom I am in search.' 'Very well,' he said, and sent for her.

“"As soon as I set eyes on her hand and wrist I cried: 'It is she, my dear host, it is she!' Without losing a moment, he ordered his servants to bring together ten respectable elderly men from the neighborhood. They came; he then sent for a sum of twenty thousand dirhems in two bags, and, addressing the ten men, said: 'I take you to witness that I give my sister here in marriage to Ibrahim, son of Mahdi, and that I bestow upon her a dowry of twenty thousand dirhems.' His sister and I both gave our agreement to the marriage, after which I gave one of the bags of money to my young wife, and distributed the other among the witnesses, saying: 'Excuse me, but this is all I have by me at present.' They accepted my present and retired.

“"My host then proposed to prepare in his own house an apartment for us. Such generosity and kindness made me feel quite embarrassed. I said that I only desired a litter to convey my wife. He readily agreed, and sent along with it so magnificent a trousseau that it entirely fills one of my houses."

“Ma’mun was astonished at the generosity of the merchant. He granted his freedom and a rich present to the parasite, and ordered Ibrahim to present his father-in-law at court. The latter became one of the most intimate courtiers and companions of the Caliph.

Death of Al Ma’mun

Abul Hasan Ali Al-Masu'di wrote: “During Al Ma’mun's last campaign against the Greek Emperor he arrived at the River Qushairah, and encamped on its banks. Charmed by the clearness and purity of its waters, and by the beauty and fertility of the surrounding country, he had a kind of arbor constructed by the banks of the stream, intending to rest there some days. So clear was the water that the inscription on a coin lying at the bottom could be clearly read; but it was so cold that it was impossible for any one to bathe in it. [Source: The Book of Golden Meadows, c. 940 CE , Charles F. Horne, ed., “The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East,” (New York: Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb, 1917), Vol. VI: Medieval Arabia, pp. 35-89, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

“All at once a fish, about a fathom in length and flashing like an ingot of silver, appeared in the water. The Caliph promised a reward to any one who would capture it; an attendant went down, caught the fish and regained the shore, but as he approached the spot where Al Ma’mun was sitting, the fish slipped from his grasp, fell into the water, and sank like a stone to the bottom. Some of the water was splashed on the Caliph's neck, chest, and arms, and wetted his clothes. The attendant went down again, recaptured the fish, and placed it, wriggling, in a napkin before the Caliph. Just as he had ordered it to be fried, Al Ma’mun felt a sudden shiver, and could not move from the place. In vain he was covered with rugs and skins; he trembled like a leaf, and exclaimed: "I am cold! I am cold!" He was carried into his tent, covered with clothes, and a fire was lit, but he continued to complain of cold. When the fish had been cooked it was brought to him, but he could neither taste nor touch it, so great was his suffering.

“As he grew rapidly worse, his brother Mutasim questioned Bakhteshou and Ibn Masouyieh, his physicians, on his condition, and whether they could do him any good. Ibn Masouyieh took one of the patient's hands and Bakhteshou the other, and felt his pulse together; the irregular pulsations heralded his dissolution. Just then Al Ma’mun awoke out of his stupor; he opened his eyes, and caused some of the natives of the place to be sent for, and questioned them regarding the stream and the locality. When asked regarding the meaning of the name "Qushairah," they replied that it signified "Stretch out thy feet" [i.e., "die"]. Al Ma’mun then inquired the Arabic name of the country, and was told "Rakkah." Now, the horoscope drawn at the moment of his birth announced that he would die in a place of that name; therefore he had always avoided residing in the city of Rakkah, fearing to die there. When he heard the answer given by these people, he felt sure that this was the place predicted by his horoscope.

“Feeling himself becoming worse, he commanded that he should be carried outside his tent in order to survey his camp and his army once more. It was now night-time. As his gaze wandered over the long lines of the camp and the lights twinkling into the distance, he cried: "O thou whose reign will never end, have mercy on him whose reign is now ending." He was then carried back to his bed. Mutasim, seeing that he was sinking, commanded some one to whisper in his ear the confession of the Muhammadan faith. As the attendant was about to speak, in order that Al Ma’mun might repeat the words after him, Ibn Masouyieh said to him: "Do not speak, for truly he could not now distinguish between God and Manes." The dying man opened his eyes—they seemed extraordinarily large, and shone with a wonderful luster; his hands clutched at the doctor; he tried to speak to him, but could not; then his eyes turned toward heaven and filled with tears; finally his tongue was loosened, and he spoke: "O thou who diest not, have mercy on him who dies," and he expired immediately. His body was carried to Tarsus and buried there.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); Metropolitan Museum of Art, Encyclopedia.com, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Library of Congress and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024