Home | Category: First Modern Humans (400,000-20,000 Years Ago)

DID MODERN HUMANS LIVE ALL OVER AFRICA, 300,000 YEARS AGO?

Early Modern Human Sites in Africa

There is broad agreement in the scientific community that Homo sapiens originated in Africa. The discovery of the world's oldest modern human fossils in Morocco in the late 2010s suggests a complex evolutionary history probably involving the entire continent, with Homo sapiens by 300,000 years ago dispersed all over Africa. Will Dunham of Reuters wrote: “Morocco was an unexpected place for such old fossils considering the location of other early human remains. Based on the shape and age of the Moroccan fossils, the researchers concluded that a mysterious, previously discovered 260,000-year-old partial cranium from Florisbad, South Africa also represented Homo sapiens. [Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, June 8, 2017]

Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian: Paleoanthropologist Jean-Jacques Hublin of Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, said the extreme age of the bones makes them the oldest known specimens of modern humans and poses a major challenge to the idea that the earliest members of our species evolved in a “Garden of Eden” in East Africa one hundred thousand years later. “This gives us a completely different picture of the evolution of our species. It goes much further back in time, but also the very process of evolution is different to what we thought,” Hublin told the Guardian. “It looks like our species was already present probably all over Africa by 300,000 years ago. If there was a Garden of Eden, it might have been the size of the continent.” [Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian, June 7, 2017 |=|]

“Scientists have long looked to East Africa as the birthplace of modern humans. Until the latest findings from Jebel Irhoud, the oldest known remnants of our species were found at Omo Kibish in Ethiopia and dated to 195,000 years old. Other fossils and genetic evidence all point to an African origin for modern humans. Hublin concedes that scientists have too few fossils to know whether modern humans had spread to the four corners of Africa 300,000 years ago. The speculation is based on what the scientists see as similar features in a 260,000-year-old skull found in Florisbad in South Africa. But he finds the theory compelling. “The idea is that early Homo sapiens dispersed around the continent and elements of human modernity appeared in different places, and so different parts of Africa contributed to the emergence of what we call modern humans today,” he said. |=|

“Lee Berger, whose team recently discovered the 300,000 year-old Homo naledi, an archaic-looking human relative, near the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage site outside Johannesburg, said dating the Jebel Irhoud bones was thrilling, but is unconvinced that modern humans lived all over Africa so long ago. “They’ve taken two data points and not drawn a line between them, but a giant map of Africa,” he said. |=|

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Homo Sapiens Rediscovered: The Scientific Revolution Rewriting Our Origins” by Paul Pettitt Amazon.com;

“A Pocket History of Human Evolution: How We Became Sapiens”

by Silvana Condemi, Francois Savatier, et al. Amazon.com;

“Ancient Bones: Unearthing the Astonishing New Story of How We Became Human” by Madelaine Böhme, Rüdiger Braun, Florian Breier (2022) Amazon.com;

“Processes in Human Evolution: The journey from early hominins to Neanderthals and modern humans” by Francisco J. Ayala and Camilo J. Cela-Conde (2017) Amazon.com;

“Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” by Yuval Noah Harari (2011) Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth” by Chris Stringer (2013)

Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes” By Svante Pääbo (2014) Amazon.com;

“The World Before Us: How Science is Revealing a New Story of Our Human Origins”

By Tom Higham (2021) Amazon.com;

“Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art” by Rebecca Wragg Sykes (2020) Amazon.com;

2000-Year-Old African DNA Suggests Humans Evolved At Least 350,000 Years Ago

Josh Davis wrote in IFL Science: “The genetics of a young child who died over 2,000 years ago in what is now South Africa is helping change our understanding of human evolution. The results show that some modern human groups within Africa split at least 260,000 to 350,000 years ago, meaning that our own species has to have evolved at some point before then. [Source: Josh Davis, IFL Science, September 29, 2017 /+]

Jean-Jacques Hublin at Jebel Irhoud

“This challenges the established timeline of our species, based on fossil evidence, which has for a long time said that Homo sapiens evolved at some point around 200,000 years ago in East Africa. It also suggests that if humans did live in southern Africa around 300,000 years ago, they were likely living alongside other hominins that are also known to have been in the region, such as the famous Homo naledi discovered a few years ago. /+\

“This latest genetic research, published in Science, has only been possible by the incredible advancements seen in recent years in the ability to extract DNA from bones found in warmer and more humid environments. This is now enabling researchers to study the fossils of hominins found in regions of Africa that until now it was thought impossible for genetic material to survive in.

“The team sequenced the genomes from seven individuals, all of which were from Southern Africa, with three dating to between 2,300 and 1,800 years ago, and four who lived around 500 to 300 years ago. They found that while the DNA of the younger remains showed evidence of admixture between different human populations, the genetics of a young boy who died some 2,000 years ago did not, and showed that his last common ancestor with other African groups was around 300,000 years ago. /+\

“The team involved in that work suggested that it seemed more and more likely that there was no single place in which humans first evolved, but that our species cropped up in multiple regions then each population mingled with each other, something that the scientists from this new study concur with.“Thus, both palaeo-anthropological and genetic evidence increasingly points to multiregional origins of anatomically modern humans in Africa,” explained Carina Schlebusch. “I.e. Homo sapiens did not originate in one place in Africa, but might have evolved from older forms in several places on the continent with gene flow between groups from different places.”“ /+\

New Model for Human Origins in Africa

Research by a team led by Dr. Brenna Henn, a population geneticist at UC Davis, published in Nature in May 2023, argues that the evolution of modern humans in Africa, as indicated by both genetic data and the diversity in the fossil record, was not result not a nice, neat branching tree but rather is best visualized as a complex “weakly structured stem” shape of divergence and coalescence. The international research team used sophisticated computer software and a large set of genomic data — including DNA from many different populations in Africa — to test a variety of models for how human populations arose and diverged, producing the genetic variation we see on the African continent today.[Source: Carlyn Zwarenstein, Salon, July 1, 2023]

In an interview with Salon, Sriram Sankararaman, an associate professor in UCLA's Departments of Computer Science, Human Genetics and Computational Medicine, praised the research team's thorough exploration of possible models and use of rich, diverse data sets. But he doubts this is the end of the story. "The resulting complexity of the model means that it's difficult to say exactly how closely it reflects reality," Sankararaman, who was not involved with the Nature study, said. "Given these models are so complicated, it's probably a reasonable thing to assume that the true models are going to be even more complicated than anything they say so far."

According to Salon: One aspect is the question of exactly whose genes are involved in all this gene flow. To explain the genetic diversity of modern groups in Africa, population geneticists have thought that ancient hominins (our now-extinct relations) might have contributed their DNA to populations that led to modern humans, as occurred in Europe, Asia and Oceania. There, significant good research shows human populations who had migrated out of Africa had sex, producing cute hairy babies at various times with two of our ancient relations, the Neanderthals and the Denisovans.

In Africa there isn't much evidence of such an "archaic admixture." There's some, but it's not definitive. "There's one particular stem which predates the split of Neanderthals from the ancestors of modern humans. And then the stem again mixes with the modern human lineage," Dr. Sankararaman said. "There's this deep population structure that is contributing to the gene pool in Africa … The question of whether this is truly archaic or not. In my mind, it's not completely settled."

Model for Human Origins in Africa Suggests There Were Two Human Groups

The model for human origins in Africa suggested in May 2023 Nature article suggests there were two human groups. Carlyn Zwarenstein wrote in Salon: The model begins approximately one million years ago, when there were not one but two main populations of humans. But instead of developing completely separately, gene flow continued between the groups over time. In place of a tree, we see a pattern of diversion from migration and reconnection through interbreeding, a bit like the veins in a leaf. Two distinct veins (or stems 1 and 2) remained weakly genetically connected through tens of thousands of years. [Source: Carlyn Zwarenstein, Salon, July 1, 2023]

Around 120,000 years ago, a merger event between populations descending from stem 1 and stem 2 gave rise to the modern day Nama people, a group of hunter-gatherers who populate South Africa, Namibia and Botswana. Not long afterwards, a different population of stem 1 descendents merged with a stem 2 population, resulting in the ancestors of Eastern and Western African populations — and everybody else outside Africa.

The researchers argue that their model, in which gene flow persisted despite divergent populations, better explains genetic diversity across the continent. It's also possible, as they concede, that further research by geneticists might still favor a hybrid explanation, in which there was some admixture from archaic hominin genes as well as the connections among populations they describe.

They say some scientists whose focus is on interpreting the fossil record have been pleased to see genetic analysis bear out what they already knew. For example, the 2017 discovery of skull fragments, a jawbone and stone tools in North Africa, dating back approximately 315,000 years, upset previous ideas that Homo sapiens evolved from a single population in East Africa. Previous assumptions were based on two skulls found in Ethiopia's Omo Valley,both of which were about 195,000 years old.

"I think the fact that we have fossils that we classify [as] somewhat sapiens that are found fairly early in multiple regions in Africa would be consistent with [our] model," Dr. Tim Weaver, another of the study authors and an anthropologist himself, explained to Salon. "The fact that we find them in various places, that's probably more consistent with this. And that's a piece of evidence that people had used to try to argue for this model before our paper came out."

On the other hand, some paleoarcheologists are very committed to the single origin idea, each arguing for the primacy of their fossil evidence for a single origin in either southern Africa, East Africa, or North Africa. "I feel like we're a bit of an empirical bunch," said Henn of her population geneticist peers. "Like, 'okay, well, the paper says this, so I'm going to update my beliefs'. And I think with the paleoanthropologists and archeologists, this may be a little bit of a different situation."

Modern Humans Arose From the Mating of Two Distinct Groups in Africa

Before modern humans arose at least 300,000 years ago, our ancestors consisted of two distinct but closely related groups that lived in Africa, a study published in the May 17, 2023 in the journal Nature found. Although these two groups had split, people within them continued to mate with the "other group" over a period of tens of thousands of years until as late as 120,000 years ago. To reach this conclusion scientists studied modern human genomes from southern, eastern and western Africa. The findings suggest our human ancestors didn't interbreed with now-extinct human relatives like Homo naledi, whose anatomy is significantly different from ours. It also debunks the idea that humans evolved from a single branch that broke off from our closest relatives. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, December 29, 2023]

Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science: These recent discoveries raised the possibility that our species may have also interbred with "ghost lineages" within Africa — ancient relatives of modern humans not currently known of in the fossil record. To shed light on this possibility, scientists analyzed modern human genomes from southern, eastern and western Africa. The study included newly sequenced genomes from 44 members of a southern African group known as the Nama. The Nama are members of the Khoe-San people, who speak a language based on clicking sounds and possess exceptional levels of genetic variants distinct from other modern humans, suggesting their ancestors may have split from those of other modern humans long ago. The team found that modern humans in Africa may descend from two or more genetically distinct streams that divided but whose individuals continued to sporadically mate over time.[Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, May 18, 2023]

The earliest signs the researchers could identify of modern humans diverging into multiple groups in Africa happened about 120,000 to 135,000 years ago, with one population splitting off to become the ancestors of the Nama. Still, before that split, the genetic variation seen in H. sapiens suggests our species consisted of two or more genetically distinct human populations that had been interbreeding for hundreds of thousands of years. The differences between these genetically distinct groups would likely have emerged because "Africa is a large continent," study co-senior author Simon Gravel, a population geneticist at McGill University in Montreal, told Live Science. Distance, geographical obstacles and social barriers would likely have helped keep these groups physically separated for the most part, and they would have diverged genetically over time, he explained. In addition, "there were also many changes in climate," study co-author Tim Weaver, a professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of California, Davis, told Live Science. The way in which rainfall or temperature levels may have risen and fallen over time "would have reduced or increased geographic barriers to human migration."

However, the researchers stressed the differences between these ancient groups would have been "almost as low as seen between contemporary human populations," Gravel said. These new findings suggest modern humans likely didn't interbreed with H. naledi or other significantly anatomically different groups — at least, not in any way they could detect in contemporary humans. "It is interesting that the new study does not find support for such interbreeding, since "we know from paleoanthropology that our likely ancestors coexisted with anatomically archaic looking forms, such as the populations represented by the Kabwe skull and H. naledi," Schlebusch said.

The new model of interbreeding with relatively anatomically similar groups may better explain the genetic variation seen in modern humans. The researchers suggested about 1 to 4 percent of genetic differences in modern human populations may come from this prehistoric intermingling in Africa.

'Ghost Population' That Mated with Ancestors of Modern Humans

Ancestors of people living in present-day West Africa appear to have reproduced with a species of ancient humans unknown to scientists, a study published in February 2020 in the journal Science Advances suggests. Our human ancestors in Europe mated with Neanderthals and ancestor of people in now living Oceania mated with Denisovans, and scientists say the genetic variation within West African populations is different enough that it is best explained by mating with a different, unknown “ghost” human species. [Source: Ryan W. Miller, USA TODAY, February 14, 2020]

Ryan W. Miller wrote in USA TODAY: “With difficulties in obtaining a full fossil records and ancient DNA, scientists' understanding of the genetic diversity within West African populations has been poor. To get a fuller picture, researchers at University of California, Los Angeles compared 405 genomes of West Africans with Neanderthal and Denisovan genomes.

“Sriram Sankararaman, one of the study's authors, told NPR that the researchers used statistical modeling to figure out which parts of the DNA they were analyzing did not come from modern humans, then compare those to the two ancient hominin species. What they found is the presence of DNA from "an archaic ghost population" in modern West African populations' genetic ancestry. “"We don't have a clear identity for this archaic group," Sankararaman told NPR. "That's why we use the term 'ghost.' It doesn't seem to be particularly closely related to the groups from which we have genome sequences from."

Sankararaman and co-author Arun Durvasula found this introgression, or sharing of genetic information between two species, between the "ghost population" and ancestors of West Africans may have occurred within the last 124,000 years. The "ghost population" likely split from humans and Neanderthals into a new species between 360,000 to 1.02 million years ago, the study says. The study also says the breeding may have occurred over an extended period of time, rather than all at once. “John Hawks, an anthropologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told The Guardian: “This interbreeding may also have a great impact on the genetic makeup of modern populations: Anywhere from 2 percent to 19 percent of their genetic ancestry could be derived from the "ghost population."

Ancestors of Modern Humans Nearly Went Extinct 900,000 Years Ago?

Between 813,000 and 930,000 years ago, the ancestors of humans went through a severe "bottleneck" when they lost about 98.7 percent of their breeding population according to a study published in August 31, 2023 in the journal Science. For more than 100,000 years, the number of our human ancestor hovered at around 1,300 individuals, a very small number. Scientists uncovered humans' "close call with extinction," by examining the genomes of 3,154 modern-day humans from both African and non-African populations. An analytical tool helped them investigate the diversity of today's genetic sequences and work backward to see what happened long ago. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, December 29, 2023]

In the study, the team used a new method called fast infinitesimal time coalescent process (FitCoal) to determine ancient demographic inferences of the genomic sequences of the 3,154 people. “The fact that FitCoal can detect the ancient severe bottleneck with even a few sequences represents a breakthrough,” study co-author and University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston theoretical population geneticist Yun-Xin FU said in a statement. FitCoal helped the team calculate what this ancient loss of life and genetic diversity looked like utilizing present-day genome sequences from 10 African and 40 non-African populations. [Source: Laura Baisas, Popular Science, September 1, 2023]

“The gap in the African and Eurasian fossil records can be explained by this bottleneck in the Early Stone Age chronologically,” study co-author and Sapienza University anthropologist Giorgio Manzi said in a statement. “It coincides with this proposed time period of significant loss of fossil evidence.”

Laura Baisas wrote in Popular Science: “Some of the potential reasons behind this population drop are mostly related to extremes in climate. Temperatures changed, severe droughts persisted, and food sources may have dwindled as animals like mammoths, mastodons, and giant sloths went extinct. According to the study, an estimated 65.85 percent of current genetic diversity may have been lost due to this bottleneck. The loss in genetic diversity prolonged a period of minimal numbers of humans who could successfully breed and was a major threat to the species.

However, this bottleneck also may have contributed to a speciation event, which happens when two or more species are created from a single lineage. During this speciation event, two ancestral chromosomes may have converged to form what is now chromosome 2 in modern humans. Chromosome 2 is the second largest human chromosome, and spans about 243 million building blocks of DNA base pairs. Understanding this split helped the team pinpoint what could be the last common ancestor for the Denisovans, Neanderthals, and Homo sapiens (modern humans). “The novel finding opens a new field in human evolution because it evokes many questions, such as the places where these individuals lived, how they overcame the catastrophic climate changes, and whether natural selection during the bottleneck has accelerated the evolution of human brain,” co-author and East China Normal University evolutionary and functional genomics expert Yi-Hsuan PAN said in a statement.

After 813,000 years ago, the study said. there was a population boom, possibly sparked by a warming climate and "control of fire". According to AFP: The researchers suggested that inbreeding during the bottleneck could explain why humans have a significantly lower level of genetic diversity compared to many other species. The population squeeze could have even contributed to the separate evolution of Neanderthals, Denisovans and modern humans, all of which are thought to have potentially split from a common ancestor roughly around that time, the study suggested. It could also explain why so few fossils of human ancestors have been found from the period. [Source: Daniel Lawler, AFP, September 15, 2023]

Doubts About the Claim That Human Ancestors Nearly Went Extinct

Some are skeptical about the claim that the ancestors of humans nearly went extinct around 900,000 years ago. One scientist told AFP there was "pretty much unanimous" agreement among population geneticists that it was not convincing. According to AFP: None denied that the ancestors of humans could have neared extinction at some point, in what is known as a population bottleneck. But experts expressed doubts that the study could be so precise, given the extraordinarily complicated task of estimating population changes so long ago, and emphasised that similar methods had not spotted this massive population crash.

It is extremely difficult to extract DNA from the few fossils of human relatives dating from more than a couple of hundred thousand years ago, making it hard to know much about them. But advances in genome sequencing mean that scientists are now able to analyse genetic mutations in modern humans, then use a computer model that works backwards in time to infer how populations changed — even in the distant past.

Archaeologists have pointed out that some fossils dating from the time have been discovered in Kenya, Ethiopia, Europe and China, which may suggest that our ancestors were more widespread than such a bottleneck would allow. "The hypothesis of a global crash does not fit in with the archaeological and human fossil evidence," the British Museum's Nicholas Ashton told Science. In response, the study's authors said that hominins then living in Eurasia and East Asia may not have contributed to the ancestry of modern humans. "The ancient small population is the ancestor of all modern humans. Otherwise we would not carry the traces in our DNA," Li said.

Stephan Schiffels, group leader for population genetics at Germany's Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, told AFP he was "extremely sceptical" that the researchers had accounted for the statistical uncertainty involved in this kind of analysis. Schiffels said it will "never be possible" to use genomic analysis of modern humans to get such a precise number as 1,280 from that long ago, emphasising that there are normally wide ranges of estimations in such research. Li said their range was between 1,270 and 1,300 individuals — a difference of just 30. Schiffels also said the data used for the research had been around for years, and previous methods using it to infer past population sizes had not spotted any such near-extinction event.

The authors of the study simulated the bottleneck using some of these previous models, this time spotting their population crash. However, since the models should have picked up the bottleneck the first time, "it is hard to be convinced by the conclusion", said Pontus Skoglund of the UK's Francis Crick Institute. Aylwyn Scally, a researcher in human evolutionary genetics at Cambridge University, told AFP there was "a pretty much unanimous response amongst population geneticists, people who work in this field, that the paper was unconvincing". Our ancestors may have neared extinction at some point but the ability of modern genomic data to infer such an event was "very weak", he said. "It's probably one of those questions that we're not going to answer."

Neanderthals, Modern Human and Denisovan Divergence

Jebel Iroud jaw and part of skull

Modern humans, or Homo sapiens, are not the descendants of Neanderthals or Denisovans, although they did live as contemporaries at one time and interbred. It remains unclear when modern humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans diverged from one another. The researchers currently estimate modern humans split from the common ancestors of all Neanderthals and Denisovans between 550,000 and 765,000 years ago, and Neanderthals and Denisovans diverged from each other between 381,000 and 473,000 years ago.

Genetic analysis revealed the parents of the woman whose toe bone they analyzed were closely related — possibly half-siblings, or an uncle and niece, or an aunt and nephew, or a grandfather and granddaughter, or a grandmother and grandson. Inbreeding among close relatives was apparently common among the woman's recent ancestors. It remains uncertain as to whether inbreeding was some kind of cultural practice among these Neanderthals or whether it was unavoidable due to how few Neanderthals apparently lived in this area, said Kay Prüfer, a computational geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

By comparing modern human, Neanderthal and Denisovan genomes, the researchers identified more than 31,000 genetic changes that distinguish modern humans from Neanderthals and Denisovans. These changes may be linked with the survival and success of modern humans — a number have to do with brain development.

"If one speculates that we modern humans carry some genetic changes that enabled us to develop technology to the degree we did and settle in nearly all habitable areas on the planet, then these must be among those changes," Prüfer said. "It is hard to say what exactly these changes do, if anything, and it will take the next few years to find out whether hidden among all these changes are some that helped us modern humans to develop sophisticated technology and settle all over the planet."

Neanderthals and Humans Split 550,000 and 765,000 Years Ago

In 2016, a team lead by Matthias Meyer,a molecular biologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, sequenced 430,000-year-old DNA from a cave in northern Spain, and has pushed back estimates of the time at which the ancient predecessors of humans split from those of Neanderthals to 550,000 and 765,000 years ago. [Source: Ewen Callaway, Nature, March 14, 2016 ]

Ewen Callaway wrote in Nature: “The analysis addresses confusion over which species the remains belong to. A report published in 2013 sequenced a femur’s mitochondrial genome — which is made up of DNA from the cell’s energy-producing structures that is more abundant in cells than is nuclear DNA. It suggested that at least one individual identified from the remains was more closely related to a group called Denisovans — known from remains found thousands of kilometres away in Siberia — than it was to European Neanderthals. “It’s wonderful news to have mitochondrial and nuclear DNA from something that is 430,000 years old. It’s like science fiction. It’s an amazing opportunity,” says Maria Martinón-Torres, a palaeoanthropologist at University College London.

“The remains are known as the Sima hominins because they were found in Sima de los Huesos (Spanish for ‘pit of bones’), a 13-metre-deep shaft in Spain’s Atapuerca mountains. Few ancient sites are as important or intriguing as Sima, which holds the remains of at least 28 individuals, along with those of dozens of cave bears and other animals. The hominins might have plummeted to their death, but some researchers think they were deliberately buried there.

“The Sima hominin skulls have the beginnings of a prominent brow ridge, as well as other traits typical of Neanderthals. But other features, and uncertainties around their age — some studies put them at 600,000 years old, others closer to 400,000 — convinced many researchers that they might instead belong to an older species known as Homo heidelbergensis. Confusion peaked when Meyer, his colleague Svante Pääbo and their team revealed the mitochondrial connection to the Denisovans. But they hoped that retrieving the skeletons’ nuclear DNA — which represents many more lines of ancestry than does mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited solely from the maternal line — would clear things up.”

The nuclear DNA, Meyer’s team,” reported in the March 14, 2016 issue of Nature, “shows that the Sima hominins are in fact early Neanderthals. And its age suggests that the early predecessors of humans diverged from those of Neanderthals between 550,000 and 765,000 years ago — too far back for the common ancestors of both to have been Homo heidelbergensis, as some had posited. Researchers should now be looking for a population that lived around 700,000 to 900,000 years ago, says Martinón-Torres. She thinks that Homo antecessor, known from 900,000-year-old remains from Spain, is the strongest candidate for the common ancestor, if such specimens can be found in Africa or the Middle East.”

Oldest Known Human Fossil Outside Africa Discovered in Israel

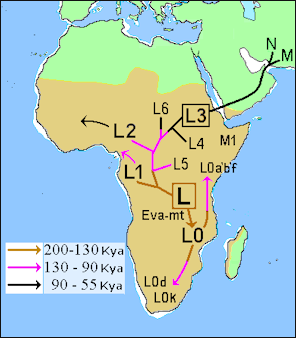

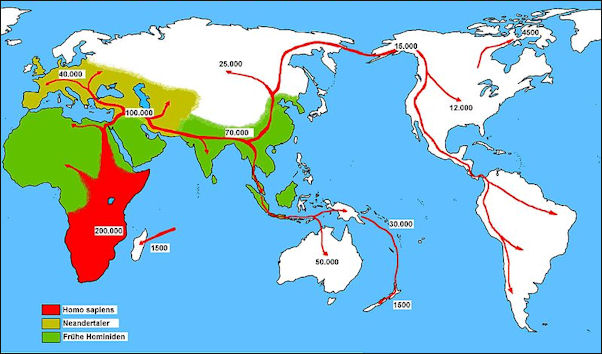

African Mitochondrial descent Hannah Devlin wrote in The Guardian: “A human upper jawbone fossil with several teeth and stone tools, dated to between 177,000 and 194,000 years old, were found in a cave in Israel, meaning that modern humans left Africa far earlier than previously thought, prompting scientists to rethink theories about early human migration. The fossil is almost twice as old as any previous Homo sapiens remains discovered outside Africa. [Source: Hannah Devlin, The Guardian, January 25, 2018 |=|]

“The fossil, a well-preserved upper jawbone with eight teeth, was discovered at the Misliya cave, which appears to have been occupied for lengthy periods. The teeth are larger than average for a modern human, but their shape and the fossil’s facial anatomy are distinctly Homo sapiens, an analysis of the fossil in the journal Science concludes. |=|

“Sophisticated stone tools and blades discovered nearby suggest the cave’s inhabitants were capable hunters, who used sling projectiles and elegantly carved blades used to kill and butcher gazelles, oryx, wild boars, hares, turtles and ostrich. The team also discovered evidence of matting made from plants that may have been used to sleep on. Radioactive dating places the fossil and tools at between 177,000 and 194,000 years old. “Hershkovitz said the record now indicates that humans probably ventured beyond the African continent whenever the climate allowed it. “I don’t believe there was one big exodus out of Africa,” he said. “I think that throughout hundreds of thousands of years [humans] were coming in and out of Africa all the time.” |=|

“Reconstructions of the ancient climate records, based on deep sea cores, show that the Middle East switched between being humid and extremely arid, and that the region would have been lush and readily habitable for several periods matching the age of the Misliya fossil.” |=|

See Separate Article: NORTHERN ROUTE VIA PALESTINE-ISRAEL AND OUT OF AFRICA THEORY africame.factsanddetails.com

Early Modern Human, Genetic Studies and Mitochondrial DNA

The human genome, is 99.9 percent identical throughout the world. By looking for DNA difference in the form of mutations and markers (the same mutation found among different people), scientists have been able glean information about where our ancient ancestors came from and how we are related to them.

Genetic studies of ancestry are based on observations of mitochondrial DNA, which is found outside the egg’s nucleus and thus combine with the genome as DNA in the egg does. Unlike chromosomal DNA, which changes when sperm and an egg fuse, mitochondrial DNA is passed on only by the mother, unchanged and unaltered, except for occasional mutations, which occur every several thousand years or so and provide distinctive markers from which common ancestry can be traced. The more differences there are between samples, the longer ago they diverged. In this way mitochondrial DNA not only tells us how similar or dissimilar two people are but also indicates how far one must go back to find a common ancestor.

By the same token most of the Y chromosomes, which determine maleness, are passed on intact from father to son. By comparing mitochondrial DNA and Y chromosomes of people from various populations, geneticists can get a rough idea of where and when groups diverged from one another in the great migrations around the world.

Some scholars warn about making too much of the study of mitochondrial DNA because patterns can be interpreted in different ways and there is no way to check for sure if they are valid or not.

Jbel Irhoud skull compared with other hominins

Eve Theory

Scientists believe that all in modern 21st century human beings descended from Eve, a hypothetical female believed to have lived somewhere in Africa around 150,000 years ago, who carried a particular type of mitochondrial DNA passed on only to female. Scientists determined this by measuring the range of variation in the DNA of different populations.

The Eve Theory was introduced in 1987 in the famous "mitochondrial Eve" article by the late Allan Wilson of the University of California, Berkeley. The theory is based on fact that mitochondrial DNA contains genetic information that is only passed down from mothers to their children and variations in population over time can be studied by examining harmless mutations passed from one generation to the next.

Wilson and his research team studied the mitochondrial DNA of women around the world and found that women of African descent have twice as much genetic diversity as non-African women. Since key mutations occurred at a steady rate, it was reasoned modern humans must have lived in Africa twice as long as anywhere else. Eve clearly was not the only woman that lived at that time but she contained genes that were passed on in an unbroken chain of mothers to the present day.

The theory has credibility not because there was only a single individual, Eve, but because the genetic lineage of all other Eves has become extinct in way the at the surnames disappear among family that have no children or only daughters. There have been several studies that have challenged the “Eve” theory. One study found much greater DNA diversity than is suggested by the Eve Theory.

According to genetic evidence the human population was reduced to around 2,000 individuals around 70,000 years ago.

Spreading homo sapiens

Archaeology magazine reported: Geneticists have sequenced the first prehistoric African genome. The DNA comes from 4,500-year-old remains found in 2012 in a cave in the Ethiopian highlands. After comparing the genome with more than 100 populations from Africa, Europe, and Asia, scientists found, surprisingly, that it includes DNA from a potentially huge migration of farmers from the Middle East into Africa around 3,500 years ago — DNA that spread across the continent, even to groups in South Africa and Congo that had long been considered genetically isolated. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2017]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Live Science, Nature, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024