Home | Category: Islam and the Qur’an / Muslim Beliefs / Islam, Muslims, God and Religion

MUSLIM MORAL BELIEFS

Shiite mullahs Islam stresses egalitarianism. The emphasis on equality and brotherhood is somewhat similar to emphasis on love in Christianity. There is a strong bond between Muslims. In his “pilgrimage of farewell,” Muhammad said, “know that every Muslim is a Muslim’s brother, and that the Muslims are brethren.”

Shariah (Islamic law) provides a blueprint of principles and values for an ideal society. At its core are the Five Pillars of Islam (1) the profession of faith, 2) prayers, 3) almsgiving, 4) fasting during Ramadan, and 5) The Hajj), which unite all Muslims in their common belief. Following the pillars involves a Muslim's mind, body, time, energy, and wealth. Meeting the obligations required by the pillars translates beliefs into actions, reinforces an everyday awareness of God's existence and presence, and reminds Muslims of their membership in a worldwide community of believers. [Source: John L. Esposito “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

The Muslim version of the Golden Rule goes: “No one of you is a believer until he desires for his brother that which he desires for himself.” An imam told National Geographic, “In the Qur’an, God commands us to be merciful with one another, to live an ethical life...The Qur’an confirms many of the teachings already laid down in the Bible. In may ways God’s message in the Qur’an boils down to “treat other better than they treat you.”

A central precept of Islam is that the injustice of others does not justify one’s own injustice. Muslims also believe in the principal of "the less of two evils." It is okay for a Muslim to eat pork to stave off starvation and it is alright for a women to get an abortion of her life is in danger.

Websites and Resources: Islam IslamOnline islamonline.net ; Institute for Social Policy and Understanding ispu.org; Islam.com islam.com ; Islamic City islamicity.com ; BBC article bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam ; University of Southern California Compendium of Muslim Texts web.archive.org ; Encyclopædia Britannica article on Islam britannica.com ; Islam at Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Muslims: PBS Frontline documentary pbs.org frontline

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Islam Explained: A Short Introduction to History, Teachings, and Culture” by Ahmad Rashid Salim Amazon.com ;

“No God but God” by Reza Aslan Amazon.com ;

“Welcome to Islam: A Step-by-Step Guide for New Muslims” by Mustafa Umar Amazon.com ;

“The New Muslim's Field Guide” by Theresa Corbin, Kaighla Um Dayo Amazon.com ;

“Islam, a Short History “ by Karen Armstrong Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Muslim World: From Its Origins to the Dawn of Modernity”

by Michael A. Cook, Ric Jerrom, et al. Amazon.com ;

”History of Arab People” by Albert Hourani(1991) Amazon.com ;

“Muslims of the World: Portraits and Stories of Hope, Survival, Loss, and Love” by Sajjad Shah , Iman Mahoui, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Beyond Belief: Islamic Excursions Among the Converted People” by V.S. Naipul (1998) Amazon.com ;

“Muhammad: A Prophet for Our Time” by Karen Armstrong Amazon.com ;

“The Messenger: The Meanings of the Life of Muhammad” by Tarqi Ramadan Amazon.com ;

“The Holy Quran” Arabic Text English Translation (English and Arabic Edition) Leather Bound

Amazon.com ;

“The Holy Qur'an with English Translation and Commentary” by Maulana Muhammad Ali Amazon.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Islam Beliefs and Teachings” by Ghulam Sarwar Amazon.com ;

“Islamic Beliefs” by Abdullah A. Hamid al-Athari and Nasiruddin al-Khattab Amazon.com ;

“The Oxford Handbook of Islamic Theology” by Sabine Schmidtke Amazon.com ;

“The Cambridge Companion to Classical Islamic Theology by Tim Winter Amazon.com ;

“Introduction to Islamic Creed” by Imam Ibrahim al-Bajuri and Rashad Jameer Amazon.com ;

“Unveiling Islam: An Insider's Look at Muslim Life and Beliefs” by Ergun Caner and Emir Fethi Caner Amazon.com ;

“Islam Explained: A Short Introduction to History, Teachings, and Culture” by Ahmad Rashid Salim Amazon.com ;

“No God but God” by Reza Aslan Amazon.com ;

“Welcome to Islam: A Step-by-Step Guide for New Muslims” by Mustafa Umar Amazon.com ;

“Islam, a Short History “ by Karen Armstrong Amazon.com ;

“Muhammad: A Prophet for Our Time” by Karen Armstrong Amazon.com ;

“The Holy Quran” Arabic Text English Translation (English and Arabic Edition) Leather Bound

Amazon.com ;

“The Holy Qur'an with English Translation and Commentary” by Maulana Muhammad Ali Amazon.com

Muslim Morality Versus Western Morality

Some scholars argue that Islam offers a different moral system than the one offered by Christianity. Unlike Christianity which seems to associate asceticism with virtue, Islam does not consider the accumulation of material wealth to be a sin. Muhammad himself was a trader. He only insisted that wealth be shared with the poor.

One reason some Muslims are hostile to the West is that they see it at decadent and immoral: Western women don’t cover themselves; men and women drink alcohol and casually engage in extramarital sex. Conservative Muslims frown upon what they see as a Western emphasis on making money, dancing and listening to music and ignore saying prayers, engaging in mediation and studying of religious texts.

Some Muslims are willing to fight to keep Western influences out of Muslim lands. A British Muslim hip-hop rapper explained: “Islam has a consciousness about it, a spiritual aspect...Islam is not against materialism and capitalism — it encourages business — but it says that they have to have a moral obligation and some form or morality.”

Charles F. Gallagher wrote in the “International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences”: The social ethic of Islam is founded upon a real sense of solidarity and brotherhood. The teachings of the Qur’an have shaped an ideal Muslim civism rooted in humility before God, piety, frugality, charity toward the less fortunate, and an equality of believers in the face of the majesty of an all-powerful Deity. The transformation from the pre-Islamic Arab character, which laid emphasis on the blood tie, vengeance, and manliness, is complete, although much of the bedouin background persists under the Islamic mantle. A summary list of grave sins reveals the influence of both strains. Ancient tribal feelings about ritual cleanliness, the eating of carrion and forbidden food, sorcery and usury, unlawful sexual relations, and the blood price coexist with unbelief, refusal to pay legal alms, apostasy, telling falsehoods about the Prophet and his companions, striking a fellow Muslim without cause, not fasting during Ramadan, and the like. [Source: Charles F. Gallagher, “International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences”, 1960s, Encyclopedia.com]

Throughout Muslim teaching and writing runs the thread of moderation in all things. The shara’ah is, literally, the “straight path” not only in the sense of righteousness opposed to deviation but also as a golden mean. Moderation and abstinence are often recommended in the Qur’an, even for acts that are permissible, and the balance they create is disturbed by the sins of greed and pride. Prodigality and lavishness of hospitality are tenacious pre-Islamic survivals in much of the Muslim East today, but they are not encouraged by the tradition. Finally, the doctrine of equality of all believers and frequent intermarriage with slaves and concubines have led to the relative absence of a color bar in Islam, a fact which today has great sociopolitical significance as well as ethical meaning.

Islam and Muslim Law

.jpg)

women in burqa in

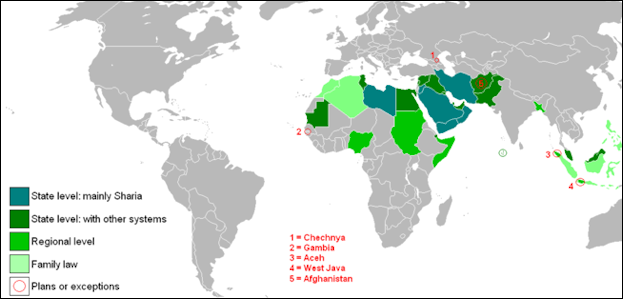

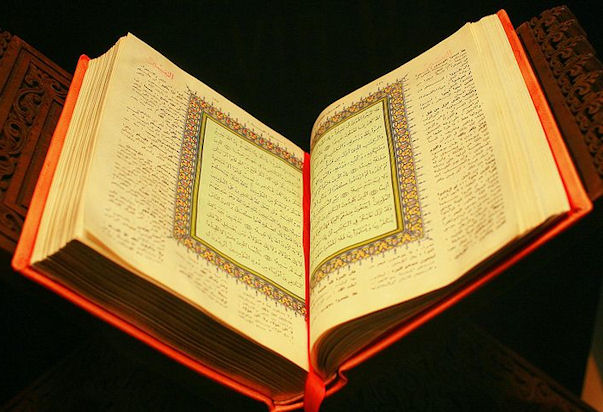

Bamdar Abbas (south Iran) Islamic Law, or “Sharia” (also “Shari'a” or “Shariah”) literally means "well-worn camel path to the watering place." It is a set of legal codes based on scriptures from the Qur’an and interpretations of these scriptures by classical Islamic schools of thought. Governing public, private, social, religious and political life of Muslims, the laws are based on the principal that Qur’anic commands are divine and absolute and can not be questioned. To break one of the rules or even doubt their legitimacy is a sin.

Muslim law tells followers how to perform their prayers, how to pay their alms, how to observe the fast. It also describes how Muslims should dress, what food Muslims can eat and even what greetings can be exchanged. Sharia is expected to be abided by as a system of laws and rules for living. It also sets forth an ethical ideal of which one is supposed to conform to.

Sharia is clearest on personal matters such as marriage, divorce and inheritance. It is not clear on commercial, penal and constitutional matters and does not address legal matters at all. In most Muslim countries the state has set up its own court system that operates independent of the Sharia courts. These non-Sharia courts have traditionally handled criminal cases and cases that deal with land and finance. If there a conflict between the two courts Sharia courts are generally considered more authoritative. The other courts have often been based on local laws. Sharia often has not been applied to non-Muslims.

H.A.R. Gibb wrote in the Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions: “Regarding Sharia as simply a complicated legal system is inadequate. As governments failed to fulfill their original functions it became the task of religious leaders to make or re-make the communal life and order to all Muslims which has given the Muslim world that psychological unity which it continue to display at the present time. The accomplishment of this task gave powerful assistance to religious leaders.”

See separate article on Muslim Law and Sharia

Dawa — The Call of Islam

Dawa is the call to Islam and propagation of the faith. All Muslims have an obligation to be an example to others and to invite them to Islam. Although it is said that Muslims do not proselytize, they have a divine mandate to preach and spread their faith. John L. Esposito wrote in the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”: The "call" (dawa) to Islam, or propagation of the faith, has been central from the origins of the Muslim community. It has a twofold meaning: the call to non-Muslims to become Muslim, and the call to Muslims to return to Islam or to be more religiously observant. From earliest times commercial and military ventures were accompanied by the spread of Islam, with traders, merchants, and soldiers its missionaries. Caliphs also used the spread of Islam as a means to legitimate their authority over Muslims and to justify imperial expansion and conquest. [Source: John L. Esposito “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Modern interpretations of dawa have taken many forms—political, socioeconomic, and cultural—as governments, organizations, and individuals have sought to promote Islam's message and impact. Governments and modern Islamic movements and organizations have supported diverse activities, including the distribution of the Koran; the building of mosques, libraries, hospitals, and Islamic schools in poor Muslim countries; and greater Islamization of law and society in Muslim countries.

As part of their foreign policies, some governments, including Saudi Arabia, Libya, and Iran, have created Dawa, or Call, organizations to promote Islam and their influence in the Muslim world and in the West. At the same time, nongovernmental Islamic organizations throughout the world have created strong networks of educational institutions and medical and social services. While the majority of these activities have been supported by mainstream groups, extremist organizations have also used social services to enhance their credibility, recruit supporters, and provide aid for the widows and families of their fighters.

Equality and Social Justice in Islam

John L. Esposito wrote in the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”: Social justice is a central teaching of the Qur’an, with all believers equal before God. The equality of believers forms the basis of a just society that is to counterbalance the oppression of the weak and economic exploitation. Muhammad, who was orphaned at an early age and who witnessed the exploitation of orphans, the poor, and women in Meccan society, was especially sensitive to their plight. Some of the strongest passages in the Qur’an condemn exploitation and champion social justice. Throughout history the mission to create a moral and just social order has provided a rationale for Islamic activist and revivalist movements, both mainstream and extremist. [Source: John L. Esposito “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

women in academic dress in Iran Muslims, like Christians and Jews before them, believe that they have been called to a special covenant with God, as stated in the Qur’an, constituting a community of believers intended to serve as an example to other nations (2:143) in establishing a just social order (3:110). The Qur’an envisions a society based upon the unity and equality of all believers, in which morality and social justice counterbalance economic exploitation and the oppression of the weak. The new moral and social order called for by the Qur’an reflects the fact that the purpose of all actions is obedience to God's law and fulfillment of his will, not individual, tribal, ethnic, or national self-interest. Men and women are equally responsible for promoting a moral order and adhering to the Five Pillars of Islam.

In response to European colonialism and industrialization, issues of social justice came to the forefront of Muslim societies in the early twentieth century. The influx of large numbers of peasants from the countryside into urban areas in many developing countries created social and demographic tensions. In Egypt, for example, the Muslim Brotherhood, founded in 1928, emerged as a major social movement whose Islamic mission included a religious solution to poverty and assistance to the dispossessed and downtrodden. Its founder, Hasan al-Banna, taught a message of social and economic justice, preaching particularly to the poor and uneducated. In al-Banna's vision Islam was not just a philosophy, religion, or cultural trend but also a social movement seeking to improve all areas of life, not only those that were inherently religious. That is, rather than being simply a belief system, Islam was a call to social action.

Islam, God, History and Politics

The historian Karen Armstrong has argued that Muslims have “looked for God in history” and their “chief duty was to create a just society” and politics “was, therefore, what Christians would call a sacrament.”

Islam is regarded as a social and political order as well as a religion. Theoretically the state and religious community are one — with both ideally being lose collections of congregations united by conservative traditions. Egalitarian and non-authoritarian, Islam is organized on state level in some places and then a local mosque level, with out much of an in between. The idea of separation of religion and the state never really caught on in the Muslim world. Secularism is viewed by some Muslims as a threat to Islam.

By contrast, politics has never been central to Judaism and Christianity. Early Jewish and Christian communities were used to living on the fringes of organized government. Christians looked for fulfillment with God in the next world and the community was not of central importance. Many liberal Muslim scholars maintain that Islam was originally a private faith that was not intended to be a guide to state matters. Sharia literally mean “the way” or “path of life,” more or less the same meaning as “Tao” and Taoism.

Many Muslims view themselves as Muslims first and citizens of a nation second. They are more likely to see themselves as a religious group divided by nations rather than a citizen of a nation comprised of different groups. One reason for this is that nations are relatively new creations for Muslims largely imposed on them by European colonial powers.

The words that Arabs used to describe many countries in the Middle East are different from those used in the West partly because Arabs do no link ethnicity and territorial identity the same way that Westerners do. The Caliph Omar, the second successor to Muhammad, reportedly said: “Learn your genealogy, and do not be like the local peasants who, when they are asked reply: “I am from such-and-such places.”

Islam, History and Modernity

There is debate whether a religion like Islam, which is based on all truths being revealed to a 7th century prophet, can adapt to and embrace change. "History." wrote one Indian Muslim scholar, " is the knowledge of the annals and traditions of prophets, caliphs, sultans, and of the great men of religion and of government. Pursuit of the study of history is particular to the great ones of religion and of government who are famous for the excellence of their qualities or who have become famous among mankind for their great deeds. Low fellows, rascals unfit people of unknown stock and mean natures, of no lineage and low lineage, loiterers and bazaar loafers — all of these have no connection with history."

Muslim fundamentalists are anti-science and anti-West. The Prophet Muhammad, they argue, was the climax of history, and therefore there is "no place for the idea of progress." These Muslims try to live their life by rules set in the seventh century. Many uneducated Arabs believe that the earth is flat and surrounded by sea and the mountains of Kaf and are suspicious of television images and photographs of a round earth viewed from space. [Source: "The Villagers" by Richard Critchfield, Anchor Books]

Egyptian Nobel-prize-winning author Naguib Mahfouz told Time that people in the West have stereotyped Arabs and Muslims as a group of "impoverished camel drivers, spendthrift oil sheikhs, cutthroat terrorists...The fundamentalist are against everything, even Islamic reformers. Let them come out into the open and show people how naked they really are, that they stand only against progress." [Ibid]

Book: “Islam and Modernity: Transformation if an Intellectual Tradition” by Fazlur Rahamn (University of Chicago Press, 1982); “ The Trouble with Islam” by Ishad Manji (Random House, 2003).

countries with sharia

Dealing with Modernity

The Iraqi-born Islamic scholar Laith Kubba told the Washington Post: “The most urgent problem facing us, the Muslims, is...a crisis of our thinking and learning process in relationship to ourselves, Islam, Muslims and humanity a large. Without an objective, relative and rational Islamic discourse, our relationship to Islam will remain as that of a sentiment to the past, or a mere slogan.”

The desire to address Islam in the modern world has bright a resurgence in “ijtihad” , the Islamic practice of independent reasoning or “exerting one’s utmost to understand.” Described by some as the intellectual counterpart of jihad, “Ijtihad” is used to come to a better understanding of an issue through serious contemplation or discussion using Islamic teachings and scripture. In the past it was seen as something that only serious scholars could engage in but is now seen as something that any serious-minded and reasonably-educated Muslim can engage in, and has blossomed in chat room on the Internet, with people often coming to different conclusion on meaning of the certain scriptures.

Some of the most radical and far reaching criticism of Islam is coming from Muslim women and feminists. Ishad Manji, a Canadian Muslim, lesbian, intellectual who doesn’t drink or eat pork and regularly reads the Qur’an, perhaps caused a big stir with her book “ The Trouble with Islam”. In it she attacks the literal interpretation of the Qur’an, condemns the holy book’s positions on Jews, women, slavery and authoritarianism, and raises the idea that the Qur’an isn’t perfect and is full of human flaws, a notion that many Muslims regarded as blasphemous.

Survey on Muslim Morality

According to the Pew Research Center: Regardless of whether they support making sharia the official law of the land, Muslims around the world overwhelmingly agree that in order for a person to be moral, he or she must believe in God. Muslims across all the regions surveyed also generally agree that certain behaviors — such as suicide, homosexuality and consuming alcohol — are morally unacceptable. However, Muslims are less unified when it comes to the morality of divorce, birth control and polygamy. Even Muslims who want to enshrine sharia as the official law of the land do not always line up on the same side of these issues. [Source: Pew Research Center, April 30, 2013]

The survey asked Muslims if it is necessary to believe in God to be moral and have good values. For the majority of Muslims, the answer is a clear yes. Median percentages of roughly seven-in-ten or more in Central Asia (69 percent), sub-Saharan Africa (70 percent), South Asia (87 percent), the Middle East-North Africa region (91 percent) and Southeast Asia (94 percent) agree that morality begins with faith in God. In Southern and Eastern Europe, where secular traditions tend to be strongest, a median of 61 percent agree that being moral and having good values depend on belief in God.10 In only two of the 38 countries where the question was asked — Albania (45 percent) and Kazakhstan (41 percent) — do fewer than half of Muslims link morality to faith in God.

Muslims around the world also share similar views about the immorality of some behaviors. For example, across the six regions surveyed, median percentages of roughly eight-in-ten or more consistently say prostitution, homosexuality and suicide are morally wrong. Medians of at least 60 percent also condemn sex outside marriage, drinking alcohol, abortion and euthanasia.

The Qur’an

Moral attitudes are less uniform when it comes to questions of polygamy, divorce and family planning. In the case of polygamy, only in Southern and Eastern Europe (median of 68 percent) and Central Asia (62 percent) do most say that the practice of taking multiple wives is morally unacceptable. In the other regions surveyed, attitudes toward polygamy vary widely from country to country. For example, in the Middle East-North Africa region, the percentage of Muslims who think polygamy is morally unacceptable ranges from 6 percent in Jordan to 67 percent in Tunisia. Similarly, in sub-Saharan Africa, as few as 5 percent of Muslims in Niger say plural marriage is morally wrong, compared with 59 percent who hold this view in Mozambique.

In sub-Saharan Africa, a median of 51 percent explicitly describe divorce as morally wrong. In other regions, fewer share this view, although opinions vary substantially at the country level. Many Muslims say that divorce is either not a moral issue or that the morality of ending a marriage depends on the situation. In the Middle East and North Africa, for instance, more than a quarter of Muslims in five of the six countries where the question was asked say either that divorce is not a moral issue or that it depends on the context.

Muslims also are divided when it comes to the morality of birth control. In most countries where the question was asked, there was neither a clear majority saying family planning is morally acceptable nor a clear majority saying it is morally wrong. Rather, many Muslims around the world say that a married couple’s decision to limit pregnancies either is not a moral issue or depends on the situation; this includes medians of at least a quarter in Central Asia (27 percent), Southern and Eastern Europe (30 percent) and the Middle East-North Africa region (41 percent).

In addition, the survey finds that sharia supporters in different countries do not necessarily have the same views on the morality of divorce and family planning. For example, in Bangladesh and Lebanon, supporters of sharia are at least 11 percentage points more likely than other Muslims to say divorce is morally acceptable. But in Albania, Kazakhstan, Russia, Kosovo and Kyrgyzstan, those who want sharia to be official law are less likely than other Muslims to characterize divorce as morally acceptable. Sharia supporters in different countries also diverge in their attitudes toward family planning. In Bangladesh, Jordan and Bosnia-Herzegovina, Muslims who want to enshrine sharia as the law of land are more likely to say family planning is moral, while in Kazakhstan, Russia, Lebanon and Kyrgyzstan, supporters of sharia are less likely to say limiting pregnancies is morally acceptable.

Reforming Islam

Muslim reformers are arguing that Islam can have many paths rather than a single path and that the religion is adaptable to changing times and conditions. Some believe that Islam will go through a process like the Christian Reformation.

George Packer wrote in The New Yorker, “Renewal and reforms — in Arabic, “tajdid” and “islah” — have an ambiguous and contested meaning in the Islamic world. They signify a stripping away of accumulated misreadings and wrong or lapsed practices, as in the Protestant Reformation.”

There are many Muslims that want to see these kinds of changes. Mansour al Nogaidan, a journalist with a Bahraini newspaper, wrote in the Washington Post: “Islam needs a Reformation. It needs someone with the courage of Martin Luther. ..Muslims are too rigid in their adherence to old, literal interpretations of the Qur’an. It’s time for many verses — especially those have to with relations between Islam and other religions — to be re-interpreted in favor or a more modern Islam.”

salat clock

One Muslim from Leeds wrote to the Times of London, “It is time Muslims accepted that it is Islam’s 8th-century attitudes that are causing so much suffering he 20th century. Please keep dogma aside and let reason be part of the debate.” Another from Washington D.C. wrote; “We believers have done enough to harm ourselves. What European monarchs and the clergy did in on the Dark and Middle Ages is exactly what Muslim rulers and clergy are doing to the Muslim world.”

Many thinks that Islam will not be reformed in the Middle East but is more likely to undergo change on the periphery of the Islamic world, in West Africa, the Sahel, South and Southeast Asia or even the West. Abdullahi Ahmed an-Main, an expert on Muslim law at Emory University, told The New Yorker “I don’t really have high hopes for change in the Arab region, because it is too self-absorbed in its own sense of superiority and victimhood.” Other parts of the Muslim world “are not noticed but that is where the hope is.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, Encyclopedia.com, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Library of Congress and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024