Home | Category: The Gospels and Early Christian Texts / Monks, Nuns and Relics

ST. CATHERINE'S MONASTERY

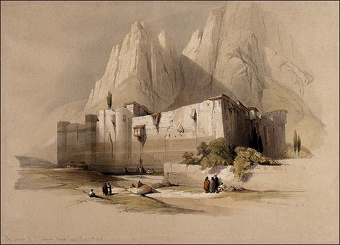

St. Catherine's Monastery is the oldest Christian monastery the world and the oldest unrestored example of Byzantine architecture. Built in the 6th century under the Byzantine emperor Justinian in an area used by cave-dwelling Christian monks, it is a combination fortress and shrine, nestled in between the slopes of Mt. Sinai. It is the traditional site of the Burning Bush, where God spoke to Moses and told him to take the Israelites to the Promised Land. Among its visitors were Emperor Justinian and Ivan the Terrible of Russia. Some even said Mohammed came here.

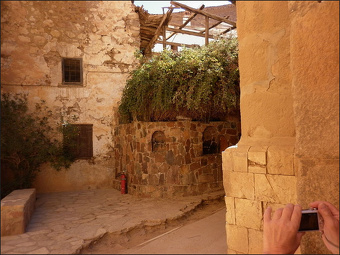

Known officially as the Imperial Monastery of the God-Trodden Mount Sinai, St. Catherine’s occupies an area about the size of a city block and resembles a small town with paved streets, small courts and whitewashed buildings piled on top of one another. The buildings are constructed of granite quarried from Mt. Sinai and some its neighboring peaks. Some of the churches have domes and others have corrugated metal roofs.

The monastery's 10-meter (34-foot) -high, two-meter (six-foot) -thick granite walls were never breached. They have holes used for firing arrows. The main landmarks there include the Basilica Church (founded by Justinian in A.D. 527), the long narrow Refectory, the Library, a Fatimid-era mosque, a 72̊C sulfur spring known as the Pharaohs bath, the Chapel of arain, the Gabal Serbal pilgrimage sight, and the 1½-mile-long Moses chain. The skull room has piles of bones and skulls from dead monks.

Jo Marchant wrote in Smithsonian magazine:“As you approach it, the sand-colored monastery, nestled low on the mountain, looks humble and timeless, like something made of the desert. Inside is a warren of stone steps, arches and alleyways; a square bell tower draws the eye upward toward the jagged mountain peaks above. Despite the rise and fall of surrounding civilizations, life here has changed remarkably little.” [Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, December 11, 2017]

Overseeing and maintaining the shrine are 25 or so Greek Orthodox monks, some form the U.S., who "grudgingly share" their sanctuary with busloads of tourists. The small mosque that stands inside the walls was built during the Crusader era and said to have been built to honor Mohammed’s visit and keep Muslim from attacking. The mosque has a minaret. The site of the burning bush is just as sacred to Muslims as it is Christians.

Websites and Resources on Christianity BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Candida Moss at the Daily Beast Daily Beast; Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ; Internet Medieval Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Saints and Their Legends: A Selection of Saints libmma.contentdm ; Lives of the Saints - Orthodox Church in America oca.org/saints/lives ; Lives of the Saints: Catholic.org catholicism.org ; Early Christianity: PBS Frontline, From Jesus to Christ, The First Christians pbs.org ; Elaine Pagels website elaine-pagels.com ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ; Gnostic Society Library gnosis.org ; Guide to Early Church Documents iclnet.org; Early Christian Writing earlychristianwritings.com ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Treasures of the Monastery of Saint Catherine” by Corinna Rossi , Araldo De Luca, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Sisters of Sinai: How Two Lady Adventurers Discovered the Hidden Gospels” by Janet Soskice Amazon.com ;

“The Desert Fathers: Sayings of the Early Christian Monks” by Benedicta Ward (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“When the Church Was Young: Voices of the Early Fathers” by Marcellino D'Ambrosio Amazon.com ;

“The Frontiers of Paradise: A Study of Monks and Monasteries” by Peter Lev Amazon.com ;

“How to Live Like a Monk: Medieval Wisdom for Modern Life” by Daniele Cybulskie and Abbeville Press Amazon.com ;

“Christ the Ideal of the Monk (Unabridged): Spiritual Conferences on the Monastic and Religious Life” by Columba Marmion Amazon.com ;

“Live Like Francis: Reflections on Franciscan Life in the World”

by Leonard Foley O.F.M. and Jovian Weigel O.F.M. Amazon.com ;

“The Benedictine Handbook” by Anthony Marett-Crosby Amazon.com ;

“Return to Mount Athos” by Father Spyridon Bailey Amazon.com

St. Catherine

St. Catherine Monastery is named after St. Catherine of Alexandria, an early Christian convert and the daughter of a ruler from Alexandria (287-305) who was martyred for upbraiding the fourth century Roman Emperor Maxentius over his persecution of the Christians. St. Catherine was interrogated about her faith by philosophers and gave brilliant answers. After she was tortured on a spiked wheel and beheaded, the story goes, her body was carried by angels to Mt. Catherine. Her hand and skull are enclosed in jeweled reliquaries in the monastery bearing her name.

According to her hagiography, St. Catherine was both a princess and a noted scholar who became a Christian around the age of 14, converted hundreds of people to Christianity and was martyred around the age of eighteen. After her death some monks established an order in her memory. More than 1,100 years after Catherine's martyrdom, Joan of Arc identified her as one of the saints who appeared to and counselled her. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Eastern Orthodox Church venerates Katherine her as a Great Martyr and celebrates her feast day on November 24 or 25, depending on the regional tradition. In Catholicism, Catherine is traditionally revered as one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers and she is commemorated in the Roman Martyrology on November 25. Her feast was removed from the General Roman Calendar in 1969, but restored in 2002 as an optional memorial.

History of St. Catherine's Monastery

St. Catherine Monastery was reportedly initially established in the 4th century with the help of St. Helen, the mother of Constantine the Great, while the fortress and basilica were originally constructed in the 6th century under the Byzantine emperor Justinian the Great. In the 6th century the monk Stephen guarded the entrance to Mt. Sinai. Today his clothed skeleton guards the ossuary at the monastery. [Source: "Island of Faith in the Sinai Deseret" by George Forsyth, January 1964 ☻]

A small community of monks has lived within the walls of St. Catherine Monastery since the 6th century. Over time Mt. Sinai became an important destination for Christian pilgrims who came to visit the holy sites around the mountain. The pilgrims were welcomed and sheltered by of monks who led lives of contemplation and prayer in the middle of the biblical desert. Today, St. Catherine’s is the world’s oldest continually occupied monastery. The Greek Orthodox monks there observe rites that have continued uninterrupted within its walls for 15 centuries. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2016]

At its height around 100 monks tended the monastery. Archaeologist Peter Grossman of the German Archaeological Institute Cairo has conducted a survey of the site, and said that thanks to granite walls, the monastery was never destroyed, and so retains architecture from all phases of its development. The small mosque was made from a converted small chapel in the tenth century and is still used for special occasions. “St. Catherine’s is better preserved than other monasteries,” Grossman told Archaeology magazine.. “Even the iron fittings of the doors in its walls and the original wooden gate of the main entrance are still in situ.”

St. Catherine's Monastery has for the most part been left undisturbed during its 1,400 year existence, but during World War I it was surrounded the Turkish Army who demanded food and supplies. The army gave the monks 24 hours to comply or else they said they would storm the monastery. The monks, prepared of such an emergency, had a secret passageway that to lead to a garden outside the compound. In the middle of the night a monk slipped out through the passage and notified a Bedouin friend with a racing camel who sped off to warn the British near Suez.☻

In 1963, the great mosaic of the Transfiguration inside the dome of St. Catherine's Monastery was on the verge of falling off the ceiling. It had stood there for 14 centuries. To save it 56 tiny holes were placed in the mosaic. Mortar was squeezed into the holes and seven copper pins were inserted to reinforce the mortar in seven critical positions. Restorers use dental picks and solvents clean old mosaics. [Source: Kurt Weitzmann, National Geographic, January 1964]

Saint Catherine Area — UNESCO World Heritage Site

The Saint Catherine Area was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2002. According to UNESCO: The Orthodox Monastery of Saint Catherine stands at the foot of Mount Horeb where, the Old Testament records, Moses received the Tablets of the Law. The mountain is known and revered by Muslims as Jebel Musa. The entire area is sacred to three Monotheistic religions: Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. The rugged mountainous landscape around, containing numerous archaeological and religious sites and monuments, forms a perfect backdrop for the Monastery. Along the Path of Moses (Sikket Sayidna Musa), leading to the summit of Mount Moses, there are two arches, the Gate of Stephen and the Gate of the Law and the remains of chapels, while the Holy Summit itself is an important archaeological site with a mosque and chapel.

Saint Catherine Area has retained its monastic function without a break from its foundation in the 6th century. The Byzantine walls protect a group of buildings of great importance both for the study of Byzantine and architecture and in Christian spiritual terms. The complex also contains some exceptional examples of Byzantine art and houses outstanding collections of manuscripts and icons.

The Saint Catherine Area is special because: 1) The architecture of Saint Catherine's Monastery, the artistic treasures that it houses, and its domestic integration into a rugged landscape, combine to make it an outstanding example of human creative genius. 2) Saint Catherine's Monastery is one of the very early outstanding examples in Eastern tradition of a Christian monastic settlement located in a remote area, demonstrating an intimate relationship between natural grandeur and spiritual commitment. It is the oldest Christian monastery retaining its function without break from its foundation until today. 4) Ascetic monasticism in remote areas prevailed in the early Christian church and resulted in the establishment of monastic communities in remote places. Saint Catherine's Monastery is one of the earliest of these and the oldest to have survived intact, being used for its initial function without interruption since the 6th century.

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: There’s a lot to see: in a chapel at the back of the Byzantine Church of the Transfiguration there is plaque that is alleged to mark the spot where God first appeared to Moses and you can see the site’s top attraction—the burning bush itself—just outside. The bush is now surrounded by a wall, which protects it from the horticulturally inclined pilgrims who use to break off pieces as religious souvenirs.

The jewel in the crown of St. Catherine’s treasure is the library. The most famous work discovered here is Codex Sinaiticus, one of the oldest copies of the Bible. It came to the attention of a German scholar, Constantine von Tischendorf, in 1844. In the course of several visits Tischendorf secured various parts of the manuscript. The Old Testament section he took back to Leipzig, but the bulk of the text he took to St. Petersburg to Tsar Alexander II. The issue is shrouded in complexity, but many people think that Tischendorf had effectively stolen this priceless manuscript. It is now housed in the British Museum. A few leaves, however, are still at St. Catherine’s and are on display in the basement of the monastery’s museum. Unusually for a monastery, there’s even a mosque, located just opposite the Church. It was built here by the monks during the 11th century. At the time Caliph Al-Hakim was destroying sites of Christian worship. The construction of the mosque kept the monastery safe from danger.

St. Catherine's Collection of Art an Icons

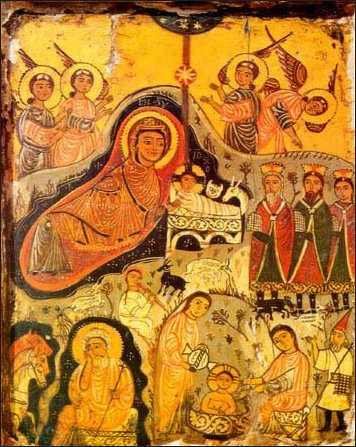

6th Century Nativity at St Catherine's Monastery

St. Catherine's Monastery arguably has the greatest collection of Byzantine manuscripts, art and iconography in the world — and ironically its isolated location is responsible for this. In all it houses 2,000 icons and 8,000 books and manuscripts. The collection of old icons is unsurpassed. Only the Vatican has better collection of very old manuscripts.

During the 8th century the Byzantine hierarchy decreed the destruction of all icons. Isolated by Islam, the order was never heard and never enforced at St. Catherine's Monastery. Consequently, nearly all the 6th and 7th century icons in the world today are found here. Its collection of 3,000 manuscripts, with texts written in Ethiopic, Syriac, Greek, Aramaic, Arabic and other languages, is equally old and equally remarkable.

The chapels of St. Catherine’s are adorned with 1,400-year-old mosaics and frescos, and festooned with tapestries and candelabras. A simple marble slab with an eternal flame in a dark sanctuary marks the spot of the burning bush. Another chapel holds reliquaries with the hand and skull of St, Catherine. In a golden casket in a marble chest are here remains. It is opened only on the holiest days.

Elsewhere in the monastery you can see an icon with John the Baptist as a dirty, unkept holy man. Another shows John the Ladder ascending to heaven with devil in pursuit. An extraordinary seventh century panel of St. Peter exhibits painting skills far ahead of its time. The most beautiful mosaic shows God commanding Moses to take off his sandals at the burning bush. Tourists have to take off their shoes before they enter many of the shrines, and unfortunately many of the monasteries extraordinary treasured are only accessible to scholars.

St. Catherine's Monastery Library

Jo Marchant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: St. Catherine’s hosts the world’s oldest continually operating library, used by monks since the fourth century. In addition to printed books, the library contains more than 3,000 manuscripts, accumulated over the centuries and remarkably well preserved by the dry and stable climate.[Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, December 11, 2017]

The first mention of its written collection comes from an account by a fourth-century pilgrim named Egeria, who described how the monks read biblical passages to her when she visited a chapel built to commemorate Moses’ burning bush. The monks at St. Catherine’s were particularly fond of reusing older parchment for their religious texts. Today the library holds at least 160 palimpsests — likely the largest collection in the world.

Rev. Justin Sinaites, who wears a long, gray beard and the black robes traditional to his faith, is the person in charge of the library. Born in Texas and brought up Protestant, Father Justin, as he prefers to be known, discovered Greek Orthodoxy while studying Byzantine history at the University of Texas at Austin. After converting to the faith, he spent more than 20 years living at a monastery in Massachusetts, where, as head of the monastery’s publications, he became adept at using computer and desktop publishing technology. In 1996, Father Justin moved to St. Catherine’s, and when the monastery’s abbot decided to digitize the library’s manuscript collection to make it available to scholars around the world, Father Justin was asked to lead the effort.

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: With more than 3,300 manuscripts, St. Catherine’s library is second only to that of the Vatican in terms of the number of ancient texts it contains. While the Vatican library was assembled carefully over the centuries, St. Catherine’s collection is different, more eclectic. “The Sinai library differs from most libraries in that it grew organically to provide the monks with copies of the scriptures and books that would inspire and guide them in their dedication,” says Father Justin, who serves as the monastery’s librarian. Many of the monks and pilgrims who came to the monastery over the centuries left manuscripts as gifts, resulting in an especially idiosyncratic collection. In addition to important Christian texts, the library contains, for instance, one of the world’s earliest known copies of the Iliad. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2016]

Codex Siniaticus and Codex Sinaiticus Syriacus

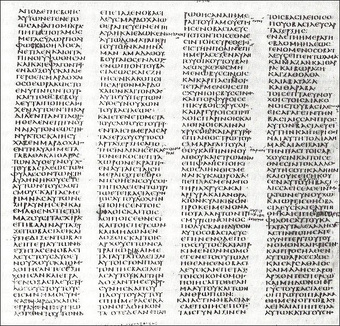

The Codex Siniaticus — dated to A.D. 325, making one of the three oldest existing manuscripts of the Bible — was taken from St. Catherine's Monastery by German scholar Konstantin von Tischendorf in 1844. In 1933 the fourth century manuscript was purchased by the British Museum from the Russian government who had confiscated it from a Orthodox church. For a century scholars have debated whether Tischendorf stole the Codex or, as he claimed, the monks entrusted it to him. The monks have a letter from Tishendorf, written in Greek and dated 1859, promising to return the Codex when he was done. [Source: "Island of Faith in the Sinai Deseret" by George Forsyth, 1964]

The Codex Sinaiticus contains the oldest known version of the New Testament. It was central to reconciling differing versions of the Bible and had led to the creation of an authoritative Greek edition of the New Testament. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2016]

According to codexsinaiticus.org: The “Codex Sinaiticus is one of the most important books in the world. Handwritten well over 1600 years ago, the manuscript contains the Christian Bible in Greek, including the oldest complete copy of the New Testament. Its heavily corrected text is of outstanding importance for the history of the Bible and the manuscript – the oldest substantial book to survive Antiquity – is of supreme importance for the history of the book.”

See Separate Article: REALLY OLD BIBLES AND THE EARLIEST CHRISTIAN WRITING europe.factsanddetails.com

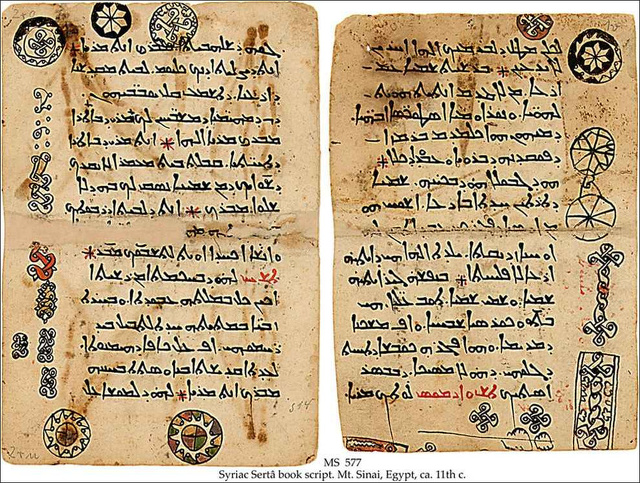

The Codex Sinaiticus Syriacus (also known as the Syriac Sinaiticus, and Sinaitic Palimpsest of Saint Catherine's Monastery and Old Syriac Gospels) is a late-4th- or early-5th-century manuscript of 179 folios, containing a nearly complete translation of the four canonical Gospels of the New Testament into Syriac, which have been overwritten by a vita (biography) of female saints and martyrs with a date corresponding to AD 697. This palimpsest is the oldest copy of the Gospels in Syriac, one of two surviving manuscripts (the other being the Curetonian Gospels). [Source: Wikipedia]

See Separate Article: HISTORY OF THE GOSPELS europe.factsanddetails.com

Monks at Saint Catherine's

St. Catherine’s, a community of 25 or so Greek Orthodox monks live more or less as their forefathers did 1,500 years ago. Every morning a bar is beaten at 3:30 in the morningto call monks to a service. The Orthodox service last from 4:00am to 7:00am, and the fathers, many of them elderly, stand through most of it. They eat a single meal at noon and spend most of their day in prayer. [Source: "Island of Faith in the Sinai Deseret" by George Forsyth, 1964 ☻]

The holy bread baked in the ovens of St. Catherine's Monastery is stamped with picture of St. Catherine and the Virgin Mary. Ostrich eggs ornament the candleabras near the Archbishops throne. The use of incense dates back to the pharaohs. The robes worn by Orthodox are derived from those worn by Roman emperors.☻

Materials in the library give insights into the lives of ancient monks as well ancient Christianity. Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Works hint at how the monks may have understood and treated illnesses, a very practical dimension of their lives.” There is also “evidence that at least some monks could have relied on the library for pleasure reading. They have identified a palimpsest containing the illustrated version of a secular fictional work, the oldest known non-biblical illustrated manuscript, perhaps suggesting that monks may have not confined themselves to religious reading. In another palimpsests scholars have been given an intimate glimpse of the monks’ spiritual lives. In it they have discovered musical notations, likely for a liturgical chant, which are still being studied. Once they are deciphered, the team may be able to recapture the sounds of one of the ancient chants that were such an integral part of religious services at the monastery. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2016]

Sisters of The Sinai

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: The study of palimpsests in St. Catherine’s library actually began in 1892 when an unlikely pair of trailblazing, self-taught biblical scholars arrived on camelback. At 49 years of age, twin Scottish sisters Agnes and Margaret Smith had made the arduous pilgrimage to St. Catherine’s Monastery in hopes of finding ancient versions of the Bible. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2016]

“The Smith twins, both widows, were passionate about studying the oldest biblical texts. To that end, they had dedicated themselves to learning 12 different languages, including both modern and ancient Greek, medieval Arabic, and Syriac, a dialect of Aramaic, a Semitic language that was once spoken and widely used as a literary language across the Middle East. The pair arrived at the monastery as some of the most learned visitors the monks had had in decades.

“The St. Catherine’s community was generally wary of outside scholars, not least because Tischendorf never made good on his promise to return the Codex Sinaiticus to the monastery. But unlike previous visitors, both women were fluent in colloquial modern Greek and so could speak with the Orthodox monks in their own language. Soon they were on friendly terms with the monastery’s librarian, and were allowed to investigate the collection, where the pair catalogued and photographed manuscripts and searched for previously unknown early versions of biblical texts. There, in an unused cabinet, Agnes found an Arabic manuscript describing the martyrdom of female saints. Though the text was not unusual, except perhaps for the somewhat racy language it used to describe the suffering of the saints, Agnes soon knew the manuscript was special. Under the Arabic text she could make out older writing in Syriac. She understood it was a palimpsest and with her command of Syriac, she knew the undertext was probably the Gospel of Mark.

“The following year, the sisters returned to the monastery in the company of three other scholars to transcribe the manuscript. This time they were armed with a chemical reagent that could dissolve the overtext’s ink and render the undertext visible. After demonstrating the technique for the monastery librarian, Agnes was allowed to apply the reagent to some leaves of the manuscript on the condition that she preserve a few lines of overtext on each page. As much as one-sixth of the undertext was rendered visible by this method.

“After several weeks spent transcribing the manuscript, the scholars found it was a complete Syriac version of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Dating to the third century, it was the oldest such account in Syriac ever discovered. Agnes edited a scholarly edition of the palimpsest Gospels, now known as the Syriac Sinaiticus, and its publication brought the sisters worldwide celebrity. Biblical scholars welcomed the discovery, and were able to use the Syriac text to resolve discrepancies that existed between different Greek versions of the Gospels. According to University of Cambridge theologian Janet Soskice, author of The Sisters of the Sinai, a biography of the sisters, the twins made an enduring contribution to biblical scholarship. “Having the Syriac version of the Gospels was a major boost to understanding the history of the Bible,” she says. “Even today, scholars are very grateful to Agnes and Margaret.”

Book: “The Sisters of Sinai: How Two Lady Adventurers Discovered the Hidden Gospels” by Janet Martin Soskice, 2009]

Manuscripts and Palimpsests from St. Catherine’s

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Sometime in the eighth century, a monk at St. Catherine’s was preparing to transcribe a book of the Bible in Arabic and needed fresh parchment. New parchment was an expensive commodity at the time and was difficult to obtain, especially for a humble monk copyist living in a remote desert monastery. Luckily for him, the venerable religious community had a massive library that included books that were no longer in use. These manuscripts, some written in extinct languages, or thought to be unimportant, were valued only for their potential as sources of recycled parchment. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2016]

No one in the monastery would have thought twice, for instance, when, while searching for writing material, the monk plucked out of the collection an ancient Greek text that had gone unread for a generation or more. None of his brothers would have batted an eye as he used a knife to carefully scrape away the centuries-old ink. Soon, the words were gone and the parchment was ready for the monk’s fresh transcription of Bible verses. Today, erasing an ancient text seems an incalculable loss, but to the eighth-century scribe, it was an act of devotion and even a measure of progress — an obsolete text was gone, and a holy manuscript that would enrich countless spiritual lives was left in its place.

“Father Justin began a program of digitizing the monastery’s collection in the late 1990s. He knew, however, that he was unable to make a record of some of the most intriguing texts in the collection. Since the late nineteenth century, scholars had been aware that many of the works in the collection are palimpsests that conceal older texts. Over the years, scholars were able to read three of the palimpsests that were legible, but the vast majority remained invisible to the naked eye and went unstudied. In 1996, a Georgian scholar used ultraviolet light to read a Sinai palimpsest with an overtext in medieval Georgian. He found that the underlying text was written in Caucasian Albanian, and was the first example of a text written in this now-extinct language. It was an exciting discovery, but the process had drawbacks. “Prolonged use of ultraviolet light is a risk to both the eyesight of the scholar and the manuscript itself,” says Father Justin. The technique just wasn’t a practical way to read the library’s palimpsests.

Sinai Palimpsests Project

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Father Justin learned of an ambitious scientific and scholarly effort under way from 1998 to 2008 to use multispectral imaging technologies to read the Archimedes Palimpsest, a tenth-century copy of the great Greek philosopher’s writings that had been overwritten by thirteenth-century Christian monks. He contacted the team decoding the Archimedes Palimpsest, and soon many of the scientists involved in the project agreed to again pool their resources to read the Sinai palimpsests. Organization of the project fell to Michael Phelps of the California-based Early Manuscripts Electronic Library, a nonprofit research group that works with universities such as UCLA and other institutions to digitize historical source materials and make them accessible for study. The Early Manuscripts Electronic Library, which uses digital technology to make ancient manuscripts available online to both scholars and the general public. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2016]

“In 2011, the Sinai Palimpsest Project began imaging some of the 130 manuscripts in St. Catherine’s library that had been identified as palimpsests. Over the course of five years, the team visited the monastery 17 times. Before each session, University of Vienna medievalist Claudia Rapp, the project’s scholarly director, would consult with Father Justin, and together they would select important palimpsests suitable for multispectral imaging. The team would then subject each page to four state-of-the-art technologies. One method developed specifically for the project involves backlighting each page with multiple wavelengths that reveal where the ink of the undertext had eroded the parchment.

“These images, once processed and viewed in combination, render long-lost words legible. As of 2016, the Sinai Palimpsest Project had imaged some 6,900 pages, collecting an unprecedented amount of data on these formerly illegible or invisible manuscripts. “I call this process the archaeology of the page,” says Rapp. “Except as we dig we don’t destroy the layers that lie above, and we’re still able to make things visible that have been hidden for centuries.”

“Twenty-three scholars are currently at work translating the palimpsests, but enough have been studied that it is now clear that St. Catherine’s library is the world’s richest source of Christian palimpsests. And the project has helped Father Justin and the monks of St. Catherine’s not just to recover lost history, but also to celebrate their faith. “The manuscripts are an inspiration to the monks who live here today,” says Father Justin, who finds the discovery of the Latin texts, in particular, very significant. “They show that there was travel and communication between East and West, at a time when scholars have presumed great isolation. This is an important example for our own times.”

“Thus far the team has imaged 75 of the manuscripts previously identified as palimpsests. In the process, Rapp has newly identified at least 30 more palimpsests in the collection. She believes that still more of the books in St. Catherine’s library may have been written on reused parchment. There could be hundreds more palimpsests yet to be discovered, an invisible library that may hold as-yet-unknown biblical texts, or more manuscripts that illuminate medieval monastic life in this remote outpost of Christianity.

Sinai Palimpsests Project Equipment and Scholarship

Jo Marchant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Father Justin brought each palimpsest out in turn to be photographed by the project’s chief camera operator, Damianos Kasotakis, who used a 50-megapixel camera custom-built in California. Photographing each page took about seven minutes, the shutter clicking repeatedly while the page was illuminated by infrared, visible and ultraviolet lights that ran across the color spectrum. The researchers toyed with different filters, lighting from strange angles, anything they could think of that might help pick out details from a page’s surface. Then a group of imaging specialists based in the United States “stacked” the images for each page to create a “digital cube,” and designed algorithms, some based on satellite imaging technology, that would most clearly recognize and enhance the letters beneath the overtext. “You just throw everything you can think of at it,” Kasotakis says, “and pray for the best.” [Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, December 11, 2017]

“Already, as a part of the Sinai Palimpsests Project, some two dozen scholars from across Europe, the United States and the Middle East are poring over these texts. As of 2017, the project had imaged 6,800 pages from 74 palimpsests and revealed more than 284 erased texts in ten languages, including classical, Christian and Jewish texts dating from the fifth century until the 12th century.

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: Project’s spectral imaging system is equipped with a high-resolution camera and a custom cradle that holds manuscripts as they are subjected to four separate imaging techniques.The original words on this reused text, or palimpsest, have been lost for over a thousand years. But now with the help of modern multispectral imaging technology, a team of scientists and scholars is able to peer through the manuscript’s visible ink and read the long-vanished text below. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2016]

Contents of the Manuscripts and Palimpsests from St. Catherine’s

The library at St. Catherine’s contains well over a hundred palimpsests, many of them offering unique insights into the early Christian era. The collection is being compared to the greatest manuscript discoveries of the 20th century, including the Nag Hammadi codices of Egypt and the Dead Sea Scrolls. The palimpsests have been studied and translated by specialists and are available online and can be read by anyone.“These are cultural treasures that are important to our common history,” says Phelps “We’re helping recover lost communities that made important spiritual and literary contributions, and allowing their voices to speak again.”

Jo Marchant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Many of the palimpsests come from a cache of about 1,100 manuscripts found in a tower of the monastery’s north wall in 1975, and consist of damaged leaves left behind when the library was moved in the 18th century, then hidden for protection after an earthquake. They are tinder dry, falling to pieces and often nibbled by rats. One of the most exciting finds is a palimpsest made up of scraps from at least ten older books. The manuscript is a significant text in its own right: the earliest known version of the Christian Gospels in Arabic, dating from the eighth or ninth century. But what’s underneath, Phelps predicts, will make it a “celebrity manuscript” — several previously unknown medical texts, dating to the fifth or sixth century, including drug recipes, instructions for surgical procedures (including how to remove a tumor), and references to other tracts that may provide clues about the foundations of ancient medicine. [Source:Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, December 11, 2017]

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: The effort has also given the team new insight into the role St. Catherine’s played in the medieval world. While it is one of the world’s most famous Christian sites, scholars have an incomplete picture of it during this period. “The history of St. Catherine’s from the seventh to the eleventh centuries is little known,” says Rapp. “The palimpsests dating to this period give us a new picture of the role the monastery played in the Christian world.” The diversity of languages found in the palimpsests, a total of 10, show that pilgrims came to St. Catherine’s from all over the Middle East and Europe. In addition to more text in Caucasian Albanian, the team has discovered palimpsests in Ethiopic, Slavonic, Armenian, and, importantly, in Latin, some written in a style that was popular in Anglo-Saxon monasteries. “We were surprised by the number of Latin texts,” says Rapp. St. Catherine’s is an Orthodox monastery and was previously not thought to have had strong links to the Latin-speaking Catholic Christian world. But the palimpsests show that a number of pilgrims from Western Europe, perhaps from as far away as Britain, made the trek to the monastery and left behind manuscripts that were then recycled.[Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2016]

“For Rapp, another significant discovery the project has made is that a number of palimpsests were written in a dialect of Aramaic known as Christian Palestinian Aramaic. This language vanished in the thirteenth century, and is poorly understood, largely because so few texts are known, making the discovery of these palimpsests especially exciting for scholars. “We have increased the number of known Christian Palestinian Aramaic texts by 30 percent,” says Rapp. “I have a colleague preparing a grammar of the language, and she’s very grateful she didn’t publish it before we found these palimpsests.”

“The content of the palimpsests also offers a look at the diversity of manuscripts that were available to monks in the early medieval period. Some of the palimpsests contain biblical texts such as fifth- and sixth-century versions of Corinthians and the book of Numbers, but they also hold a number of secular works that monks could have consulted. The team has identified a variety of medical writings, including a treatise on medicinal plants, which contains a treatment for scorpion stings, the earliest surviving texts of Hippocratic medical works, and a previously unknown version of a list of medical terms.

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons

Text Sources: Smithsonian magazine, Archaeology magazine, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, and other publications.

Last updated March 2024