Home | Category: Passion, Death and Resurrection of Jesus / Basic Christian Beliefs

MEANING OF THE DEATH OF JESUS

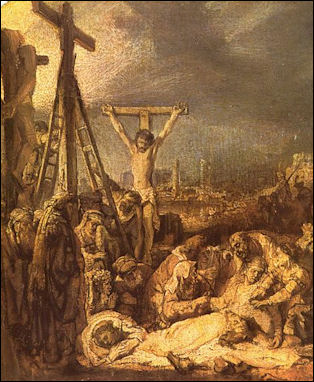

Entombment by Rembrandt According to the BBC: “The New Testament uses a range of images to describe how God achieved reconciliation to the world through the death of Jesus. The most common is the image of sacrifice. For example, John the Baptist describes Jesus as "the lamb of God that takes away the sins of the world". (John 1:29) Here are some other images used to describe the atonement:

1) a judge and prisoner in a law court; 2) a payment of ransom for a slave's freedom; 3) a king establishing his power; 4) a military victory. [Source: BBC, September 18, 2009 |::|]

“Did Jesus take the punishment for humanity's sins when he died on the cross? That idea is called penal substitution and is summed up by Reverend Rod Thomas, from the evangelical group Reform, as "When God punished he showed his justice by punishing sin but he showed his love by taking that punishment himself". |::|

Professor Shaye I.D. Cohen told PBS: “The most difficult thing for us after 2000 years is to bring our imagination down when we're looking at the passion of Jesus. Because we want to think the whole world was watching, or all of the Roman Empire was watching, or all of Jerusalem was watching. I take it for granted there were standing orders between Pilate and Caiaphas about how to handle, lower class especially, dissidents who cause problems at Passover. If it was an upper class person, a very important aristocrat, of course, they would be shipped off to Rome for judgment. That would be handled completely differently. What would happen to a peasant who caused trouble in the Temple and maybe endangered a riot at Passover? Standing orders, I would take it, crucifixion, as fast as possible. Hang him out as a warning. We're not going to have any riots at Passover. That's, I think, what happened to Jesus. What happened in the Temple caused his death. And I don't imagine any, for example as we find in John's gospel, dialogues between Jesus and Pilate.

Websites and Resources: Jesus and the Historical Jesus Britannica on Jesus britannica.com Jesus-Christ ; PBS Frontline From Jesus to Christ pbs.org ; Life and Ministry of Jesus Christ bible.org ; Jesus Central jesuscentral.com ; Catholic Encyclopedia: Jesus Christ newadvent.org ; Complete Works of Josephus at Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org ; Christianity BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ; Candida Moss at the Daily Beast Daily Beast Christian Answers christiananswers.net ; Bible: Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Resurrection of Jesus: Apologetics, Polemics, History” by Dale C. Allison Jr, Jim Denison, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Case for the Resurrection of Jesus” by Michael R. Licona, Gary R. Habermas, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Crucifixion of Jesus: A Medical Doctor Examines the Death and Resurrection of Christ” by Joseph Bergeron M.D. Amazon.com ;

“The Crucifixion of Jesus, Completely Revised and Expanded: A Forensic Inquiry”

by Frederick T. Zugibe Amazon.com ;

“The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ” by Fleming Rutledge Amazon.com ;

“The Crucifixion of the King of Glory: The Amazing History and Sublime Mystery of the Passion” by Eugenia Scarvelis Constantinou PhD, Eugenia Scarvelis Constantinou, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Trial and Crucifixion of Jesus, The: Texts and Commentary Paperback” by David W. Chapman, Eckhard J. Schnabel Amazon.com ;

“What Christ Suffered: A Doctor's Journey Through the Passion” by Thomas W McGovern MD Amazon.com ;

“Jesus of Nazareth: Holy Week: From the Entrance into Jerusalem to the Resurrection”

by Pope Benedict XVI, Matthew Arnold, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Mystery of the Last Supper: Reconstructing the Final Days of Jesus” by Colin J. Humphreys Amazon.com ;

“The Church of the Holy Sepulchre: The History of Christianity in Jerusalem and the Holy City’s Most Important Church” by Kosta Kafarakis Amazon.com ;

“The Architectural History of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem” by Robert Willis Amazon.com

Why Did Jesus Die?

Christians believe the death of Jesus was part of a divine plan to save humanity. But exactly how could this work? Atonement and reconciliation, Theories of the Atonement and Penal substitution are all issues that have bearing on how his death is perceived.

Professor Paula Fredriksen told PBS: “It's unclear how he actually gets into trouble. He wouldn't have wandered into the crosshairs of the Priests, because compared to how the Pharisees are criticizing the Priests, what Jesus is doing is fairy minimal.... If he had been complaining about the Priests, or criticizing them, or criticizing the way the Temple was being run, this would just [be] business as usual; this is one of the aspects of being a Jew in second Temple Judaism. So it's really quite unclear how he would have gotten into trouble for religious reasons, which are the reasons the gospels are concerned to construct. [Source: Paula Fredriksen, William Goodwin Aurelio Professor of the Appreciation of Scripture, Boston University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“I think we have to settle firmly on the historical fact that he was crucified and therefore, killed by Rome.... I would prefer, rather than try to invent or import some kind of improbable religious reason for him getting into trouble and then trying to explain how a religious authority could somehow seduce or cajole Pilate into obliging them and executing Jesus, I prefer a simpler hypothesis. To think that he was turned over to Rome because there was a perceived danger, that Pilate, who has a terrible reputation for the way he behaved when he went up to Jerusalem for these pilgrimage holidays, was on the verge of some kind of muscular crowd control. People would get hurt or killed when Pilate felt so moved. And perhaps for this reason Jesus was turned over to Rome, and sure enough, Pilate, consistent with the record we know of him elsewhere, kills Jesus. But Pilate killed lots of people.

Why Were Jesus’s Followers Not Harmed?

Disciples leave their hiding places to "watch from afar in agony"

Professor Paula Fredriksen told PBS: “That's right. Jesus' followers are not rounded up and killed. Only Jesus is killed. That's one of the few firm facts we have about it. What this means, at the very least, is that nobody perceived Jesus as the dangerous political leader of a revolutionary movement. If anybody had thought he was a leader of a revolutionary movement, then more than Jesus, probably, would have been killed.... [Source: Paula Fredriksen, William Goodwin Aurelio Professor of the Appreciation of Scripture, Boston University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“I think there's some kind of cooperation between the chief priests and Pilate. The chief priests always had to cooperate with Rome because it's their job. They're mediating between the imperial government and the people. Particularly at Passover, which is a holiday that vibrates with this incredible historical memory of national creation and freedom.

“And there's Rome and the Roman soldiers standing among the colonnade of the Temple looking down at Jews celebrating this. So it's a politically and religiously electric holiday. And it's in this context that Jesus is turned over to Rome, lest there be, I think, some kind of popular activity. The gospels depict him as preaching about the Kingdom of God in the Temple courtyard in the days before Passover. That could be enough. That could be enough right there.

Atonement and Redemption

Atonement and redemption represent the belief that Jesus died for the sins of everyone who has faith in God. It holds that Jesus died for the sins of humanity so the faithful, people who accepted Jesus into their hearts, could ascend to heaven and have eternal life, despite their sins. The Apostle Paul wrote: “God shows his love for us in that while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us...We are now justified by his blood.”

The word Atonement essentially means oneness with god (“at-one-ment”) and describes the desire by humans to have a relationship with God and achieve this by reaching a sinless state often by suffering or offering penitence. According to John, Jesus was aware of his atonement when he said, “I am the living bread which came down from heaven; if anyone eats this bread, he will live forever; and the bread which I shall give for the life of the world is my flesh.”

Redemption describes the process — through Christ’s death — that atonement can be achieved by absolving oneself of one’s sins. Both concepts have their roots in Jewish sacrifices. According to Hebrews in the New Testament, Jesus killed “not the blood of goats and calves but his own blood, thus securing eternal redemption.”

Some believe that Jesus’s death took place the way it did because the burden of human sin was so great that humanity could never possibly pay it back and only God, through Jesus, could do so through the pain of the Crucifixion. Others have argued it was a “divine bait-and-switch scheme” to fool the devil, by getting devil was focus his energy on trying to tempt Jesus and in the process dropped his guard, allowing all of humanity the opportunity to find salvation.

Atonement

Lament the Dead Christ by Rembrandt Atonement essentially means that Jesus accepted the pain of death to show, through his Resurrection, that God and his love are not defeated by death. His sacrifice was a kind of compensation for all the sins that have ever been committed by humankind, allowing sinners — which is more or less everyone — to achieve salvation and have a relationship with God. According to I John 3:16: “This is the proof of love, that he laid down his life for us, and we ought to lay down our lives for our brothers.”

According to Encyclopedia.com: The doctrine of Atonement speaks of reconciliation between God and humankind, a settlement ending the separation between God and humans. This separation was caused, according to some interpretations, by Original Sin. (The doctrine of Original Sin says that sin, or disobedience to God, began when Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden.) This Original Sin had to be paid for, and it was the suffering and death of Jesus on the cross that redeemed humanity. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

Others see this separation in a more psychological (dealing with the human mind) manner. For example, the word sin has roots that are similar to the word sunder, meaning "to split" or "to divide." In this interpretation Original Sin represents the sense of alienation, or distancing, that humans have from one another and from God. Through belief in Jesus people can erase sin and achieve a sense of oneness. For Christians, belief in the Atonement of Jesus is the way to salvation.

See Separate Article: ORIGINAL SIN europe.factsanddetails.com

Redemption

According to Encyclopedia.com: That human beings are sinful is a theological statement of the observable fact that men and women are persistently self-centered and that even their highest moral achievements are quickly corrupted by selfishness. Yet although we thus fail, exhibiting a chronic moral weakness and poverty, our failure is not inevitable; we are ourselves, at least in part, responsible for it. The biblical story of the fall of man depicts this situation by means of the myth that man was originally created perfect but fell by his own fault into his present state, in which he is divided both in himself and from his fellows and God. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

At its primary level of belief Christianity claims that by responding to God's free forgiveness, offered by Christ, men are released from the guilt of their moral failure (justification) and are drawn into a realm of grace in which they are gradually re-created in character (sanctification). The basis of this claim is the Christian experience of reconciliation with God and, as a consequence, with other human beings, with life's circumstances and demands, and with oneself. The "justification by faith" of which Paul spoke, and which represented the main religious emphasis of the Reformation of the sixteenth century, means that men are freely accepted by God's gracious love, which they have only to receive in faith. In Paul Tillich's contemporary restatement, a man has only to accept the fact that although unacceptable even to himself, he is accepted by God.

In this case, work at the secondary level of theological reflection did not begin seriously until the church had been preaching the fact of divine reconciliation and atonement for about a thousand years. Anselm, in the eleventh century, taught that the death of Christ constituted a satisfaction to the divine honor for the stain cast upon it by man's disobedience, and this remains the core of Catholic atonement doctrine. Martin Luther and John Calvin, in the sixteenth century, spoke of Christ's death as a substitutionary sacrifice by which Christ suffered in his own person the punishment that was justly due humankind, and this remains the core of official Protestant atonement doctrine. In the nineteenth century, however, the thought was developed (going back to Anselm's contemporary Peter Abelard) that God's forgiveness does not need to be purchased by Christ's death, but that this brings home to the human heart both man's need for divine forgiveness and the reality of that forgiveness. There were in the twentieth century and on into the twenty-first century continuing efforts to understand Christ's redeeming work in a way that would bring together the valid insights in these and other traditional views, each of which by itself has seemed one-sided.

Atonement and Reconciliation

“According to the BBC: “The events leading up to the arrest and crucifixion of Jesus are well-told by the Gospel writers, as are stories of the Resurrection. But why did Jesus die? In the end the Roman authorities and the Jewish council wanted Jesus dead. He was a political and social trouble-maker. But what made the death of Jesus more significant than the countless other crucifixions carried out by the Romans and witnessed outside the city walls by the people of Jerusalem? [Source: BBC, September 18, 2009 |::|]

“Christians believe that Jesus was far more than a political radical. For them the death of Jesus was part of a divine plan to save humanity. The death and resurrection of this one man is at the very heart of the Christian faith. For Christians it is through Jesus's death that people's broken relationship with God is restored. This is known as the Atonement. |::|

“What is the atonement? The word atonement is used in Christian theology to describe what is achieved by the death of Jesus. William Tyndale introduced the word in 1526, when he was working on his popular translation of the Bible, to translate the Latin word reconciliation. In the Revised Standard Version the word reconciliation replaces the word atonement. Atonement (at-one-ment) is the reconciliation of men and women to God through the death of Jesus. |::|

“But why was reconciliation needed? Christian theology suggests that although God's creation was perfect, the Devil tempted the first man Adam and sin was brought into the world. Everybody carries this original sin with them which separates them from God, just as Adam and Eve were separated from God when they were cast out of the Garden of Eden. |::|

“So it is a basic idea in Christian theology that God and mankind need to be reconciled. However, what is more hotly debated is how the death of Jesus achieved this reconciliation. |There is no single doctrine of the atonement in the New Testament. In fact, perhaps more surprisingly, there is no official Church definition either. But first, what does the New Testament have to say? |::|

Theories of the Atonement

Atonement

According to the BBC: “Theologians have grouped together theories of the atonement into different types. For example, in Christus Victor (1931) Gustaf Aulén suggested three types: classical, Latin and subjective. More recently in his book Christian Theology: An Introduction Alister E. McGrath groups his discussion into four central themes but stresses that these themes are not mutually exclusive. His four themes are: 1) The cross as sacrifice; 2) The cross as a victory; 3) The cross and forgiveness; 4) The cross as a moral example. [Source: BBC, September 18, 2009 |::|]

“The cross as sacrifice: The image of Jesus' death as a sacrifice is the most popular in the New Testament. The New Testament uses the Old Testament image of the Suffering Servant (Isaiah 53:5) and applies it to Christ. The theme of Jesus's death as a sacrifice is most drawn out in the Letter to the Hebrews. The sacrifice of Christ is seen as the perfect sacrifice. In the biblical tradition sacrifice was a common practice or ritual. In making an offering to God or a spirit, the person making the sacrifice hopes to make or mend a relationship with God. |::|

“St Augustine too wrote on the theme of sacrifice: By his death, which is indeed the one and most true sacrifice offered for us, he purged, abolished and extinguished whatever guilt there was by which the principalities and powers lawfully detained us to pay the penalty. — Augustine - The City of God “He offered sacrifice for our sins. And where did he find that offering, the pure victim that he would offer? He offered himself, in that he could find no other. — Augustine - The City of God |::|

“The cross as a victory: Jesus on the cross against a red sky. The New Testament frequently describes Jesus's death and resurrection as a victory over evil and sin as reprsented by the Devil. How was the victory achieved? For many writers the victory was achieved because Jesus was used as a ransom or a "bait". In Mark 10:45 Jesus describes himself as "a ransom for many". This word "ransom" was debated by later writers. The Greek writer Origen suggested Jesus's death was a ransom paid to the Devil. |::|

“Gregory the Great used the idea of a baited hook to explain how the Devil was tricked into giving up his hold over sinful humanity: ‘The bait tempts in order that the hook may wound. Our Lord therefore, when coming for the redemption of humanity, made a kind of hook of himself for the death of the devil.’ — Gregory the Great |::|

“‘Although the victory approach became less popular in the eighteenth century amongst Enlightenment thinkers - when the idea of a personal Devil and forces of evil was thrown into question - the idea was popularised again by Gustaf Aulén with the publication in 1931 of Christus Victor.’ — Aulén wrote of the idea Christus Victor: |::|

“‘Its central theme is the idea of the Atonement as a Divine conflict and victory; Christ - Christus Victor - fights against and triumphs over the evil powers of the world, the 'tyrants' under which mankind is in bondage and suffering, and in Him God reconciles the world to Himself.’ — Gustaf Aulén |::|

Was Atonement Borrowed from Yom Kippur

It has been argued that early Christians used the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur to explain why it was that people needed saving, and how the death of Jesus could save other people. Yom Kippur, is the holiest day in the Jewish calendar. It lasts roughly for 25 hours and involves fasting and intensive prayer. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The biblical basis for the Day of Atonement can be found in Leviticus 16, which describes a series of religious rituals and animal sacrifices that had to be performed in the Jerusalem Temple in order to keep the Temple clean. Ritual sacrifices were offered year round so it’s strange that a special day was required, but Yom Kippur was something like a religious deep clean. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, October 8, 2019]

Professor Liane Feldman, who teaches in the department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies at NYU, explained that “anything that slipped through the cracks or hasn’t been cleaned up yet or can’t be cleaned up by regular [sacrificial] offerings is taken care of by a series of five sacrifices offered on this day.” The reason behind the obsession with ritual cleanliness is that the Temple was the home of God. As Feldman puts it. “the Israelite God cannot live in an impure place.” If the Temple gets too dirty then there’s the risk that God might leave (which is a thing that God actually does in Ezekiel).

The most intriguing part of the religious rituals is the mention of a goat over which the high priest confesses the sins of the Israelites and transfers the sins from the Temple to the goat. These sins are the most serious kind: they are intentional sins (sins you deliberately and brazenly commit). “The contamination caused by intentional sins can’t be cleaned up, it can only be moved from one place to another,” said Feldman. After the transfer of sins to the goat, to which was attached a red yarn collar, the goat was dispatched into the wilderness to “Azazel.” Writing sometime later, the rabbis — who were understandably concerned that the goat might trot back with its burden — weren’t content to just send the goat into the wilderness and, thus, insisted that the goat be pushed off a cliff and died. Feldman mentioned one rabbinic tradition in which a piece of red yarn is also tied to the Temple door. When the goat gets outside the community the yarn is supposed to turn white. The ritual is the origins of the modern term “scapegoat.”

Given that ancient Greeks sacrificed people and the Bible describes elaborate rituals to eliminate sin, it’s easy to see why early Christians would use the same logic to discuss the significance of the death of Jesus. In the Gospel of John, Caiaphas, the High Priest states that “it is better for you to have one man die for the people than to have the whole nation destroyed” (11:50). This logic is richly explored in the Epistle to the Hebrews, one of the less well-known texts in the New Testament, in which Jesus is depicted as both the High Priest performing the sacrifices and the sacrificial offering itself. Harold Attridge, the Sterling Professor of Divinity at Yale, explained that “early Christians had to make sense of the death of Jesus” and the Epistle to the Hebrews cleverly used the day of atonement to do just that. What these New Testament authors are trying to explain is why Jesus died and how his death was significant, and in doing that they turned to Yom Kippur to explain both why it was that people needed saving and how it was that the death of Jesus could save other people.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “ How Christianity Co-Opted Yom Kippur to Explain Jesus’ Death” by Candida Moss in the Daily Beast thedailybeast.com

Salvation

Salvation means deliverance from sin and its consequences. Christians believe this is a result Jesus Christ's dying on the cross and grace — the unmerited gift from God for human salvation For Christians, belief in the Atonement of Jesus is the way to salvation. Through salvation is believed one can attain eternal life. In Romans 10:9: Paul says: If you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved."

One of the things that makes Christianity different from other religions is the emphasis on free will and the conversion process. Many saints had deeply moving conversion experiences or visions, In “Varieties of Religious Experience” . William James wrote: “A genuine first-hand religious experience...is bound to be a heterodoxy to its witnesses: the prophet appearing as a mere lonely madman. If his doctrine proves contagious enough to spread to any others, it becomes a definite and labeled heresy. But if then still proves contagious enough to triumph over persecution, it becomes itself an orthodoxy, and when a religion has become an orthodoxy, its day of inwardness is over: the spring is dry: the faithful live at second hand exclusively and stone the prophets on their turn.”

The modern concept of salvation is something that developed over time. The original notion professed by Paul was intended to free man from rigid Jewish laws, saying all that was necessary to receive the grace of God was having a willingness to follows his “Way." This was taken to mean that salvation was achieved by living a Christian life, performing good deeds and conducting oneself in a moral way.Later salvation came to mean the reward that one received after deciding to devote oneself to Christ. The key scripture here from John): Jesus said, “Let not your heart be troubled; ye believe in God, believe also in men. In my Father’s house are many mansions: if it were not so, I would have told you. I go to prepare a place for you...that where I am, there ye may be also.” The idea here was that salvation occurs first and moral conduct will follow as a natural consequence.

Conversions: See Separate Article: ST. PAUL: HIS LIFE, CONVERSION AND DEATH europe.factsanddetails.com ; ST. AUGUSTINE: HIS LIFE, CONFESSIONS AND CONVERSION europe.factsanddetails.com ; ST. FRANCIS: HIS LIFE STORY, CONVERSION, TRAVELS, STIGMATA europe.factsanddetails.com

Salvation Theology

Michael J. McClymond wrote in the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”: The Christian doctrine of salvation follows from the doctrine of sin. Because human beings are estranged, God undertakes to bring them back into a closer relationship with him: "In Christ God was reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them" (2 Corinthians 5:19). The process starts with God's eternal will to bring salvation (election, or predestination); unfolds as human beings exercise faith and repentance; ushers sinners into a new relationship of gracious acceptance by God; finds expression in the daily struggle to grow in faith, obedience, and holiness before God; and reaches its culmination when believers are raised from the dead and transformed into a glorious and immortal state. Orthodox theology speaks of salvation as "divinization" or "deification" (Greek, theosis), a process whereby human beings are brought to share in God's own life and so participate in his holiness and glory. [Source: Michael J. McClymond, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Roman Catholic, Orthodox, and many Anglican Christians view salvation as something mediated through the Christian community. In this view salvation comes through participation in the church, with baptism as the sign of that participation. Traditional Catholic theology states that unbaptized persons cannot be saved. Following baptism, a believer's strengthening in the faith comes from participation in the Eucharist and the other sacraments — confirmation, penance (reconciliation), holy orders (ordination), matrimony, and extreme unction (anointing of the sick). Some Catholic theologians emphasize the correct performance of the rituals, though others stress the importance of approaching the sacraments in faith. Like Catholics, Orthodox and Anglican Christians understand the church to be a sacramental community. In these traditions the church exhibits an unbroken line of leaders, or "apostolic succession," extending from the first century to the present time. Catholics emphasize the succession of Roman bishops, or popes, beginning with Peter (Matthew 16:17–19), as the leaders of Christendom, while Orthodox and Anglican Christians hold that the bishops collectively share in decision making and responsibility.

Protestants show a less communal interpretation of salvation, Christian life, and church leadership. Luther had been a faithful monk and yet lacked "assurance of salvation," which he found through Bible reading and a conversion experience in which God's mercy suddenly became real to him. Since that time Protestants have stressed the Bible and personal experience of God. Neither the outward forms of the church nor baptism and the sacraments are as important as the individual's experience of Christ. Most Protestants hold to two basic church rituals — baptism and the Eucharist. Lutherans and Calvinists hold that the outward actions are genuine sacraments with spiritual power attached to them. Baptists, Pentecostals, and nondenominational Protestants believe that the outward actions are merely signs attesting to and confirming the faith of those who share in them. Thus, this latter group of Protestants baptize only adults and older children on a profession of faith (believer's baptism). Though all Protestants deny the supreme spiritual authority of the papacy, they differ as to what they put in its place. Anglicans, Methodists, and Lutherans preserve the ancient system of church government by bishops, while Baptists, Pentecostals, and Congregationalists allow each local gathering to govern itself, with Presbyterians placing local gatherings under the direction of a representative assembly.

Did the Christian Idea of Salvation Come From Mystery Cult Initiations?

Roger Beck of the University of Toronto Mississauga wrote for the BBC: “The Greek word mystêrion denotes initiation. Baptism initiates you into the Christian mystery, for example; and yes, early Christianity both can and should be classified with the pagan mystery cults. [Source: Professor Roger Beck, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Initiation brings you into a relationship with the god or gods of the cult. Much as Christian initiation brings you into a relationship with Jesus, the Christ, so initiation into the pagan mysteries brings you into a relationship with ‘Egyptian’ Isis, or ‘Persian’ Mithras, or home-grown Dionysus-Bacchus, or one or other of the several Great Mother goddesses and their junior consorts (Cybele and Attis for example). |::|

“If asked to define the essence of the ‘relationship’ in a single word most initiates would probably reply with the Greek or Latin words (sôtêria, salus) meaning the state of being ‘safe and sound’, of being ‘saved’. ‘Salvation’ is also a fair translation, provided we remember that for most pagan initiates it would mean physical and material protection, health and well-being vouchsafed by the god, with or without the bonus of spiritual rescue now and in the hereafter. |::|

“By initiation into a mystery you enter a community of fellow initiates. Now fellowship in a bleak world, where pain and poverty are the norms, is a precious commodity. In market terms, it enhances a firm’s competitiveness. Apart from Judaism, only two religious 'firms' in antiquity developed this feature of community life to the full: Christianity and Mithraism. |::|

See Separate Article: CULTS IN THE GREEK AND ROMAN WORLD europe.factsanddetails.com MYSTERY CULTS IN THE GREEK AND ROMAN WORLD europe.factsanddetails.com

Violence, Suffering and the Crucifixion

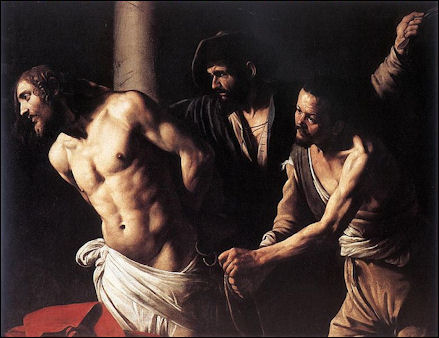

Flagellation by Caravaggio Morbidity and violence are a central themes of Christianity as well as peace and compassion — especially among Catholics — at least as representations of some famous paintings and images of Christ and Mel Gibson’s film “The Passion” . These are tied to the violent nature of Jesus’s death.

The Passion as a source of lurid iconography blossomed in Europe the 1300s, when much of the continent suffered through the Great Plague, Mogul invasions and other ills. Paintings and sculptures of a suffering Christ appeared in great numbers; cults grew about relics associated with the crucifixion; and people came to believe that meditating on it could help redeem the human race.

Christianity was one of the first religions to make suffering a virtue rather something that was pathetic. Christ’s suffering on the cross was something to be admired rather than pitied. There was a prevailing view in medieval times that no matter how much people suffered, Christ suffered even more. One mystic reported that Christ came to her in a vison and told her, “I was beaten on the body 6,666 times; beaten on the head 110 times; pricks of thorns in the head, 110..mortal thorns in the head, 3...the drops of blood that I lost were 28,430.” Violent depictions of Christ returned un the 16th and 17th centuries during the Counter-Reformation when Catholic painters in Italy and Spain used graphic images of violence to stir up the masses to fight the upstart Protestants. Images of suffering Christ remain particularly common today in Latin American churches.

Is Suffering and Persecution Part of Being a Christian?

There is strong belief that Christianity was built on suffering and violent persecution but New Testament scholar Candida Moss disagrees. She wrote in te Daily Beast: For Christians, the crucifixion is the event that changed everything. Prior to the death of Jesus and the emergence of Christianity most ancient people interpreted oppression, persecution, and violence as a sign that their deity was either irate or impotent. The crucifixion forced Jesus’s followers to rethink this paradigm. The death of their leader was reshaped as triumph and the experience of persecution became a sign of elevated moral status, a badge of honor. The genius of the Jesus movement was its ability to disassociate earthly pain from divine punishment. As a result Christians identified themselves as innocent victims; they associated their sufferings with those of Jesus and aligned the source of those sufferings with the forces that killed Jesus. From the very beginning, victimhood was hardwired into the Christian psyche. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, March 31, 2013]

The belief that Christians are continuously persecuted has a basis in Scripture. In the Gospel of Mark, Jesus instructs his followers to take up their cross and follow him and predicts that his followers will be persecuted for his name. Then again, in the very same passage he predicts that some of those standing before him will not taste death before the arrival of his kingdom in glory. Why do we accept the prophecy of persecution when the statement about the disciples living until the last judgment clearly failed? The reason why Jesus’s statements about persecution have had such a pronounced impact on the formation of Christian identity is that this prophecy is believed to have been proven in the experiences of the early church. The Church has suffered since the beginning, the argument goes, and we are persecuted now as we have always been.

This idea of constant attack and Christian victimhood is grounded in the myths of the early church, but it endures to this day. It is evident in the rhetoric of modern American media pundits, politicians, and religious leaders who proclaim that there is a war on Christianity in modern America. The problem with identifying oneself and one’s group as a persecuted minority is that it necessarily identifies others as persecutors. It is certainly the case that Christians — and members of other religious groups — around the world endure horrifying violence and oppression today. But it is rarely those voices or calls for action on their behalf that reach our ears. On the contrary, these experiences are drowned out by louder, local complaints.

Instances of oppression, violence, and persecution do not need a history of persecution or a commitment to victimhood to support them. The mistreatment of Christians in modern India, for example, is not wrong because it is part of a history of persecution. It is just wrong. Nor is it somehow more outrageous than violence against Muslims or Hindus there.

Most importantly, the myth of persecution can actually generate violence. At the beginning of the first Crusade, Pope Urban II promised Christian soldiers the rewards of martyrdom if they died in the conflict. The historical factors are complicated, and medieval European Christians did see themselves as under attack, but their actions cannot be dismissed as “self-defense.” This is a cautionary example for us. There is always the possibility that we have no sense of our own position in a conflict. Even though we cast ourselves as martyrs, we might be crusaders.

The example of Jesus that hangs at the center of Christianity encouraged his followers to embrace suffering and to stand firm in times of persecution. But even if Christians are called to embrace suffering and victimization, we can do without a story of persecution that is inaccurate, unproductive, and polarizing. Nor should we build our interpretation of the present on errors about the past.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “The Death of Jesus and the Rise of the Christian Persecution Myth” by Candida Moss

Cross and Forgiveness and a Moral Symbol

According to the BBC: “Anselm of Canterbury writing in the eleventh century rejected the idea that God deceived the Devil through the cross of Christ. Instead he presented an alternative view which is often called the satisfaction theory of the atonement. In this theory Jesus pays the penalty for each individual's sin in order to right the relationship between God and humanity, a relationship damaged by sin. [Source: BBC, September 18, 2009 |::|]

“Jesus's death is the penalty or "satisfaction" for sin. Satisfaction was an idea used in the early church to describe the public actions - pilgrimage, charity - that a christian would undertake to show that he was grateful for forgiveness. Only Jesus can make satisfaction because he is without sin. He is sinless because in the Incarnation God became man. The theory is thought out by Anselm in his work Cur Deus Homo or Why God became Man. |::|

“Moral influence theories or exemplary theories comprise a fourth category used to explain the atonement. They emphasise God's love expressed through the life and death of Jesus. Christ accepted a difficult and undeserved death. This demonstration of love in turn moves us to repent and re-unites us with God. Peter Abelard (1079-1142) is associated with this theory. He wrote: ‘The Son of God took our nature, and in it took upon himself to teach us by both word and example even to the point of death, thus binding us to himself through love.’ — Peter Abelard |::|

“Abelard's theory and the call to the individual to respond to Christ's death with love continues to have popular appeal today: ‘Our redemption through the suffering of Christ is that deeper love within us which not only frees us from slavery to sin, but also secures for us the true liberty of the children of God, in order that we might do all things out of love rather than out of fear - love for him that has shown us such grace that no greater can be found.’ — Peter Abelard |::|

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org; New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org , Frontline, PBS, “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, 1994); Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Live Science, Encyclopedia.com, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, Business Insider, AFP, Library of Congress, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024