Home | Category: Literature

SUMERIANS, PRODUCERS OF THE WORLD’S OLDEST STORIES

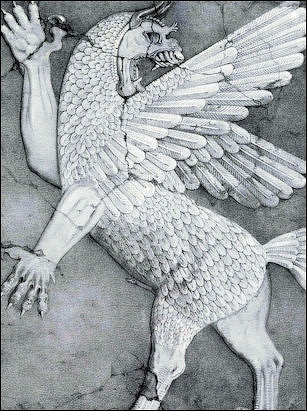

Anzu

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: The oral literature of the Sumerians, while continuing in its own medium, must gradually have explored the possibilities of using writing as an aid in memorizing. While the innately written genres were, as has been seen, in general oriented toward serving as reminders and organizing data, the genres which originated as oral genres, and only secondarily took written form, had as a whole a different aim. A magical aspect may be distinguished in oral literature, retained in its pure form in the genre of incantation, where the spoken word is meant to call into actual existence that which it expresses; the more vivid the incantation, the more effective it is, a fact which accounts for its being cast in literary, or even poetic, language and form. The incantation was the province of a professional performer, the incantation priest (Sum. mašmaš, Akk. ašipu).[Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

According to Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature: "The literature written in Sumerian is the oldest human poetry that can be read, dating from approximately 2500 B.C. onwards. It includes narrative poetry, praise poetry, hymns, laments, prayers, songs, fables, didactic poems, debate poems and proverbs." In can also be argued that the Sumerians produced the world’s oldest stories as narrative poems are stories. The Sumerologist Bendt Alster. discusses the topic in the following scholarly article: "On the Earliest Sumerian Literary Tradition", Alster, Bendt, Journal of Cuneiform Studies 28, 1976. 109-126..

Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature: etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk . It contains an overview of Sumerian literature. According to their cataloguing system: "An initial 1 indicates compositions with a high narrative content, 1.1 to 1.7 being ones in which deities are the principal protagonists and 1.8 ones in which legendary heroes such as Lugalbanda play that role." There is a catalog at: etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk .

Lugalbanda and the Anzud Bird ( etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk ) is regarded as one of the oldest Sumerian stories and the cuneiform tablets on which it is written are in excellent condition. Lugalbanda is mentioned in the Sumerian King List as ruling in Sumer before the famous king Gilgamesh. The Anzud bird was a mythological thunderstorm bird depicted with the roaring head of a lion and the flying body of an eagle. [Source: John Alan Halloran, sumerian.org]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The First Ghosts” by Irving Finkel (2021) Amazon.com;

“From Distant Days: Myths, Tales, and Poetry of Ancient Mesopotamia” by Benjamin R Foster (1995) Amazon.com;

“Wisdom Literature in Mesopotamia and Israel” (Society of Biblical Literature Symposium)

by Richard J. Clifford (2007) Amazon.com;

“History and Myth from Sumer and Akkad: The Oldest Stories” by James Bleckley (2023)

Amazon.com;

“Sumerian Mythology” by Samuel Noah Kramer (1998) Amazon.com;

“Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others” by Stephanie Dalley (1989) Amazon.com;

“The Legend of Etana and the Eagle” by James Kinnier Wilson (1985) Amazon.com;

“Enuma Elish: The Babylonian Creation Epic: also includes 'Atrahasis', the first Great Flood myth” by Timothy J. Stephany Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian Genesis” by Alexander Heidel (1942) Amazon.com;

“Atra-Hasis: The Babylonian Story of the Flood” by W. G. Lambert and Alan R. Millard (1969) Amazon.com;

“Berossos and Manetho, Introduced and Translated: Native Traditions in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt” by Gerald Verbrugghe (1996) Amazon.com;

Three Ox-Drivers from Adab

“Three Ox-Drivers from Adab” goes: “There were three friends, citizens of Adab, who fell into a dispute with each other, and sought justice. They deliberated the matter with many words, and went before the king. "Our king! We are ox-drivers. The ox belongs to one man, the cow belongs to one man, and the waggon belongs to one man. We became thirsty and had no water. [Source: J.A. Black, G. Cunningham, E. Robson, and G. Zlyomi 1998, 1999, 2000, Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford University, piney.com]

“We said to the owner of the ox, "If you were to fetch some water, then we could drink!". And he said, "What if my ox is devoured by a lion? I will not leave my ox!". We said to the owner of the cow, "If you were to fetch some water, then we could drink!". And he said, "What if my cow went off into the desert? I will not leave my cow!". We said to the owner of the waggon, "If you were to fetch some water, then we could drink!". And he said, "What if the load were removed from my waggon? I will not leave my waggon!". "Come on, let's all go! Come on, and let's return together!" " "First the ox, although tied with a leash , mounted the cow, and then she dropped her young, and the calf started to chew up the waggon's load. Who does this calf belong to? Who can take the calf?"

” The king did not give them an answer, but went to visit a cloistered lady. The king sought advice from the cloistered lady: "Three young men came before me and said: 'Our king, we are ox-drivers. The ox belongs to one man, the cow belongs to one man, and the waggon belongs to one man. We became thirsty and had no water. We said to the owner of the ox, "If you were to draw some water, then we could drink!". And he said, "What if my ox is devoured by a lion? I will not leave my ox!". We said to the owner of the cow, "If you were to draw some water, then we could drink!". And he said, "What if my cow went off into the desert? I will not leave my cow!". We said to the owner of the waggon, "If you were to draw some water, then we could drink!". And he said, "What if the load were removed from my waggon? I will not leave my waggon!" he said. "Come on, let's all go! Come on, and let's return together!" ' "

" 'First the ox, although tied with a leash , mounted the cow, and then she dropped her young, and the calf started to chew up the waggon's load. Who does this calf belong to? Who can take the calf?" ' [35 lines missing, The cloistered lady continues her reply to the king:) "Well now, the owner of the ox, ...... his field ....... After his ox has been eaten by a lion ......, his field ......." "The hero....... Like a mountaineer ....... A dog ...... the ox ....... A strong man ...... in his field......."

"Well now, the owner of the cow ...... his wife. After his cow has gone off into the desert ......, his wife will walk the streets ....... After the cow has dropped its young ......, the hero, walking in the rain ....... His wife ...... herself. The ox's food ration which he has turned to his ......, ...... hunger. His wife dwells with him in his house, his desired one ...... "

"Well now, the owner of the waggon, after he has abandoned his ......, and the load has been removed from his waggon, and ...... from his waggon, and after he has brought his ...... into his house, ...... will be made to leave his house. His calf that began to chew up the waggon's load will be ...... in his house. When he has approached ...... the open-armed hero, the king, having learnt about his case, will make his ...... leave his dwelling ...... the ox, ...... has partaken of my wisdom, shall not oppose it. His load, ......, will not return ."

“When the king came out from the cloistered lady's presence, each man's heart was dissatisfied. The man who hated his wife left his wife. The man ...... his ...... abandoned his ....... With elaborate words, with elaborate words, the case of the citizens of Adab was settled. Pa-nijin-jara, their sage, the scholar, the god of Adab, was the scribe.”

See Abraham and the Ox Cart travel to Canaan

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

Ancient Mesopotamian Dispute Literature

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: One of the most popular forms of entertainment and humorous examination of standard values was the dispute or logomachy (an argument about words), which seems to have flourished particularly under the rulers of the Third Dynasty of Ur, several of whom are referred to by name in these works. The usual pattern is a mythological introduction setting the action in the beginning of time, which is then followed by a lengthy dispute about their respective merits by the two contestants. Sometimes the end of the tale is a judgment by a god or the king, but other settings occur, and the text may launch directly into the debate. Examples of works in this genre are "Summer and Winter," "Silver and Copper," "Ewe and Grain," "Plow and Hoe," "Shepherd and Farmer," and others. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

As a rule, the more lowly contestant carries the day. A special group of such disputes have the school or the life of a scribe as a setting. Among these are "A Scribe and His Disappointing Son," in which a father details the many failings of his son — one senses that he has spared the rod too much — as also "The Overseer and the Scribe," in which the scribe lists the numerous services a scribe performs in a large household, "Enkimansum and GirnIIsag," a dispute between an obstreperous student and his tutor, and "The Dispute between Enkita and Enkihegal," which, as the disputants get more and more heated, deteriorates into a mere slanging match. It would seem that the ancient listeners must have derived a good deal of vicarious enjoyment from hearing of quarreling and listening to the unrestrained flow of bad language, for in this genre such things are frequent.

Another example of it, perhaps the worst, is a vitriolic slanging match known as "Debate Between Two Women." The most interesting evaluative work of Sumerian wisdom literature is, however, probably the one called "Man and His God," in which a man complains about his god's neglecting him and the bad luck dogging him as a consequence. It is a Sumerian precursor, in some sense, of later treatments of the motif of the just sufferer and the earliest indication of awareness of the problem we have.

The genres of disputes also continued with new compositions such as a "Dispute between the Horse and the Bull." A new creation — based on the omen form — is a text warning rulers against mistreating Babylon and its citizens. It dates most likely from early in Sennacherib's reign. Humor seems to be represented — outside of the proverb literature — by the so-called "Dialogue of Pessimism" (cos i, 495–96), an ironical dialogue between a fickle master and his slave, and by the story of a poor man getting his revenge on an abusive official called "The Poor Man of Nippur."

Mesopotamian Fables and Proverb and Wisdom Literature

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: Apodictic statements of do's and don'ts characterize the extensive proverb genre, which comprises actual proverbs, as well as all kinds of saws, turns of phrase, etc. and also includes short fables with pointed morals. A large collection of such saws was attributed to Shuruppak, father of the Sumerian hero of the Flood, Ziudsudra, and appear in the composition "The Instructions of Shuruppak" as this wise father's counsels to his son. This composition was, as mentioned, already in existence in the Abu Salabikh materials. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

New and notable contributions to the genre of wisdom literature are two long poems, Ludlul belnêmeqi, "Let me Praise the Expert" (cos i, 492), which treats the theme of the righteous sufferer, and the Theodicy (cos i, 492–95), which deals with the problem of the worldly success of the wicked. The proverb tradition continues, and new material is added, especially, it appears, fables.

The composition commonly called the "Farmer's Almanac," which is cast in the form of a father's — the plow-god Ninurta's — advice to his son, and describes in order all the standard activities to be carried out by a good farmer during the year, is apodictic and didactic insofar as it presents a norm for the activities of the farmer. Formally similar in many ways is the composition called "Schooldays," in which a schoolboy takes time out on his way to school to tell a questioner where he is going so early in the morning, and what he usually does in school.

Worm and the Toothache

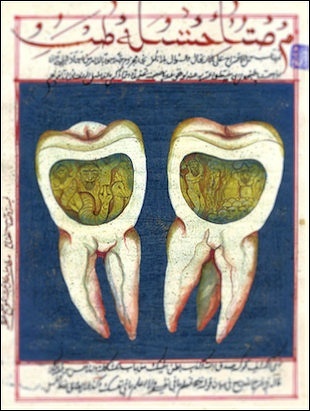

18th century Ottoman depiction of tooth worms

“The Worm and the Toothache” reads:

After Anu had created heaven,

Heaven had created the earth,

The earth had created the rivers,

The rivers had created the marsh,

And the marsh had created the worm---

The worm went, weeping, before Shamash,

His tears flowing before Ea:

"What will you give me for food?

What will you give me to suck on?"

"I will give you the ripe fig and the apricot."

"What good is the ripe fig and the apricot?

Lift me up, and assign me to the teeth and the gums!

I will suck the blood of the tooth,

and I will gnaw its roots at the gum!"

Because you have said this, O worm,

May Ea strike you with the might of his hand!

[Source: Translated by E. A. Speiser, Ancient Near Eastern Texts Related to the Old Testament, edited by J. B. Pritchard (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 100-101, piney.com]

Story of Ahikar, Grand Vizier of Assyria

The First Chapter of the “Story of Ahikar, Grand Vizier of Assyria” — “ The story of Haiqar the Wise, Vizier of Sennacherib the King, and of Nadan, sister's son to Haiqar the Sage” — goes:

2 There was a Vizier in the days of King Sennacherib, son of Sarhadum, King of Assyria and Nineveh, a wise man named Haiqar, and he was Vizier of the king Sennacherib.

3 He had a fine fortune and much goods, and he was skilful, wise, a philosopher, in knowledge, in opinion and in government, and he had married sixty women, and had built a castle for each of them.

4 But with it all he had no child by any of these women, who might be his heir.

5 And he was very sad on account of this, and one day he assembled the astrologers and the learned men and

the wizards and explained to them his condition and the matter of his barrenness.

6 And they said to him, 'Go, sacrifice to the gods and beseech them that perchance they may provide thee with a boy.' [Source: Ahikar Aramaic papyrus of 500 B. C. in the ruins of Elephantine - the Jewish temple in Egypt, “The Lost Books of The Bible and The Forgotten Books of Eden,” Crane, Second Section, pgs 198-219, Alpha House]

7 And he did as they told him and offered sacrifices to the idols, and besought them and implored them with request and entreaty.

8 And they answered him not one word. And he went away sorrowful and dejected, departing with a pain at his heart.

9 And he returned, and implored the Most High God, and believed, beseeching Him with a burning in his heart, saying, '0 Most High God, 0 Creator of the Heavens and of the earth, o Creator of all created things!

10 I beseech Thee to give me a boy, that I may be consoled by him, that he may be present at my death, that he may close my eyes, and that he may bury me.'

11 Then there came to him a voice saying, 'Inasmuch as thou hast relied first of all on graven images, and hast offered sacrifices to them, for this reason thou Shalt remain childless thy life long.

12 But take Nadan thy sister's son, and make him thy child and teach him thy learning and thy good breeding, and at thy death he shall bury thee.'

13 Thereupon he took Nadan his sister's son, who was a little suckling. And he handed him over to eight wet-nurses, that they might suckle him and bring him up.

14 And they brought him up with good food and gentle training and silken clothing, and purple and crimson. And he was seated upon couches of silk.

15 And when Nadan grew big and walked, shooting up like a tall cedar, he taught him good manners and writing and science and philosophy.

16 And after many days King Sennacherib looked at Haiqar and saw that he had grown very old, and moreover he said to him.

17 '0 my honoured friend, the skilful, the trusty, the wise, the governor, my secretary, my vizier, my Chancellor and director; verily thou art grown very old and weighted with years; and thy departure from this world must be near.

18 Tell me who shall have a place in my service after thee.' And Haiqar said to him, '0 my lord, may thy head live for ever! There is Nadan my sister's son, I have made him my child.

19 And I have brought him up and taught him my wisdom and my knowledge.'

20 And the king said to him, '0 Haiqar ! bring him to my presence, that I may see him, and if I find him suitable, put him in thy place; and thou shalt go thy way, to take a rest and to live the remainder of thy life in sweet repose.'

21 Then Haiqar went and presented Nadan his sister's son. And he did homage and wished him power and honour.

22 And he looked at him and admired him and rejoiced in him and said to Haiqar: 'Is this thy son, 0 Haiqar? I pray that God may preserve him. And as thou hast served me and my father Sarhadum so may this boy of thine serve me and fulfil my undertakings, my needs, and my business, so that I may honour him and make him powerful for thy sake.'

23 And Haiqar did obeisance to the king and said to him 'May thy head live, 0 my lord the king, for ever! I seek from thee that thou mayst be patient with my boy Nadan and forgive his mistakes that he may serve thee as it is fitting.'

24 Then the king swore to him that he would make him the greatest of his favourites, and the most powerful of his friends, and that he should be with him in all honour and respect. And he kissed his hands and bade him farewell.

25 And he took Nadan his sister's son with him and seated him in a parlour and set about teaching him night and day till he had crammed him with wisdom and knowledge more than with bread and water.

Creation of the Pickax

The Myth of the Creation of the Pickax or Hoe adds some details to the creation of mankind: Enlil removed heaven from earth in order to make room for seeds to come up. After he created the hoe he used it to break the hard crust of earth in Uzumua (the flesh-grower), a place in the Temple of Inanna in Nippur. Here, out of the hole made by Enlil's hoe, man grew forth. [Source: Kenneth Sublett, piney.com]

early stone age ax

The Creation of the Pickax by Enlil (the Babylonian Holy Spirit) goes:

The lord did verily produce the normal order,

The lord whose decisions cannot be altered,

Enlil quickly removed heaven from earth

So that the seed, from which the nation grew, could sprout up from the field;

He quickly brought the earth out from under the heaven as a separate entity

And bound up for the earth the gash in the "bond of heaven and earth"

So that the earth could grow humankind.;

He created the pickax when daylight was shining forth,

He organized the tasks, the pickman's way of life;

Stretching out his arm straight toward the pickax and the basket,

Enlil sang the praises of his pickax.

He drove his pickax into the earth.

In the hole which he had made was humankind.

While the people of the land were breaking through the ground,

He eyed his black-headed ones in steadfast fashion.

The pickax and the basket build cities,

The steadfast house of the pickax builds, the steadfast house of the pickax establishes,

The steadfast house it causes to prosper.

The house which rebels against the king,

The house which is not submissive to its king,

The pickax makes it submissive to the kingÉ

The pickax, its fate is decreed by father Enlil,

The pickax is exalted.

Lugalbanda and the Anzu Bird

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica:In the epic called after him Lugalbanda is still a young man. It relates how Enmerkar calls up his army for a campaign against the city of Aratta in the eastern highlands. On the march, Lugalbanda falls seriously ill and is left to die in a cave ( urrum) in the mountains by his fellows. He partly recovers, however, and begins fervently to pray to the gods for help. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

The gods hear his prayers and as he roams the mountains he comes upon the nest of the thunderbird, Anzu, gains its favor, and is granted, at his own wish, supreme powers of speed and endurance. The bird also helps him find his way back to the army, and there, among his comrades, Lugalbanda completely recovers. The army reaches Aratta and begins a long siege of it. However, after a while Enmerkar's zest for the task wanes and he wishes to send a message back to Uruk to Inanna, upbraiding her for no longer caring enough for him; she must choose between him and her city Aratta.

There is, however, no messenger who dares undertake the hazardous journey. At last Lugalbanda volunteers, and successfully carries the message to Inanna. She receives him well, hears Enmerkar's message, and advises Enmerkar to catch a certain fish on which Aratta's life depends. Thus he will put an end to the city. Its craftsmen, handiwork, copper and moulds for casting, he can then take as spoil.

See Separate Article: LUGALBANDA AND THE ANZU BIRD africame.factsanddetails.com

Enmerkar Epics

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: There are two other epics of which Enmerkar is the hero: "Enmerkar and Suhkesdanna" and "Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta." The first of these is a romantic epic verging on fairy tale. It tells how Ensuhkesdanna of Aratta sent messengers to Enmerkar in Uruk, demanding that he submit to Aratta since Ensuhkesdanna could provide a temple of lapis lazuli and a richly adorned couch for the rite of the sacred marriage with Inanna, while Enmerkar had but a temple of mud brick and a bed of wood to offer. The demand is, as could be expected, proudly refused, and Ensuhkesdanna then wishes to obtain his demands by force of arms. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

The assembly in Aratta is not willing to support him in this, however, and so he is temporarily at an impasse. Then an incantation priest (mašmaš) and magician at his court offers to use his powers to have a canal dug to Uruk and to have the inhabitants load their possessions on boats and haul them to Aratta. Ensuhkesdanna is delighted and rewards him richly. The magician then sets out from Aratta, and arriving on his way at Nidaba's city Eresh near Uruk he persuades — since he can speak the language of animals — the cows and goats there to stop giving milk, thus interrupting the cult of Nidaba. At the complaint of the herders, a learned amazon goes up against him in a sorcerer's contest in which both cast fish spawn into the river and pull out animals: the magician, a fish, and the amazon, a bird, which flies off with the fish; the magician, an ewe and its lamb, the amazon, a wolf that runs off with them, and so forth. After the fifth try the magician is exhausted, it becomes dark before his eyes, and he is all confused. The amazon chides him, saying that while his wizardry is plentiful, his judgment is sadly lacking in that he has tried his wizardry against the holy city of Nidaba. So saying, the amazon seized his tongue in her hand and, denying his plea for mercy on the grounds that his crime was sacrilegious, killed. Word of his fate reached Aratta, and Ensuhkesdanna, much sobered, acknowledged the preeminence of Enmerkar.

The other epic about Enmerkar makes of the rivalry between Enmerkar and the lord of Aratta a battle of wits, a test of which of them is most competent as ruler. In its scale of values, peaceful compromise seems to win out over military solutions. It begins by telling how Enmerkar appealed to Inanna to make her other city, Aratta, subject to Uruk, so that its people would bring down stone and other precious building materials as tribute to Uruk for Enmerkar's temple building. Inanna grants his wish, tells him to send a messenger to Aratta to demand submission, and withholds rain from Aratta, in order to put pressure on it to submit. The ruler of Aratta at first rejects the demand, but when he is told that Inanna sides with Enmerkar he accedes pro forma: he will submit if Enmerkar will send grain to relieve the famine caused by the drought, but this grain must not be sent in sacks, it must be loaded into the carrying nets of donkeys. Enmerkar complies with this seemingly impossible demand by sending sprouted grain and malt, but is set a new similar, seemingly impossible condition. After he had complied with that and still another, he loses patience, however, and threatens to destroy Aratta. His angry message is too long for the messenger to remember, and so to help him Enmerkar invents the letter. When the messenger arrives in Aratta with the written letter and the lord of Aratta is pondering it to think of a new subterfuge, the god of rainstorms, Ishkur, apparently knowing nothing about what is going on, drenches the region around Aratta, producing a bumper crop. At this point, unfortunately, the text is incompletely preserved. From what we have, however, it is possible to gather that the conflict was resolved by the invention of trade and a peaceful exchange of goods follows. Thus Enmerkar is able to obtain his coveted building materials through peaceful means.

Hullupu Tree: Version One

In days of yore, in the distant days of yore,

In nights of yore, in the far-off nights of yore,

In days of yore, in the distant days of yore,

After in days of yore all things needful had been brought into being,

After in days of yore all things needful had been ordered,

After bread had been tasted in the shrines of the Land,

After bread had been baked in the ovens of the Land,

After heaven had been moved away from earth,

After earth had been separated from heaven,

After the name of man had been fixed,

After An had carried off heaven,

After Enlil had carried off earth,

After Ereshkigal had been carried off into the nether world as its prize --

[Source: “The Sumerians,” Samuel Noah Kramer, p. 199, piney.com]

After he had set sail, after he had set sail,

After the father had set sail for the nether world,

Against the king, the small were hurled,

Against Enki, the large were hurled,

Its small stones of the hand,

Its large stones of the dancing reeds,

The keel of Enki's boat,

Overwhelm in battle like an attacking storm,

Against the king, the water at the head of the boat,

Devours like a wolf,

Against Enki, the water at the rear of the boat,

Strikes down like a lion.

[Enki is the patron god of music and arts. Inanna stole the power of music.]

Once upon a time, a tree, a huluppu, a tree —

It had been planted on the bank of the Euphrates,

It was watered by the Euphrates —

The violence of the South Wind plucked up its roots,

Tore away its crown,

The Euphrates carried it off on its waters.

The woman, roving about in fear at the word of An,

Roving about in fear at the word of Enlil,

Took the tree in her hand, brought it to Erech:

"I shall bring it to pure Inanna's fruitful garden."

The woman tended the tree with her hand, placed it by her foot,

Inanna tended the tree with her hand, placed it by her foot,

"When will it be a fruitful throne for me to sit on," she said,

"When will it be a fruitful bed for me to lie on," she said.

The tree grew big, its trunk bore no foliage,

In its roots the snake who knows no charm set up its nest,

In its crown the Imdugud-bird placed its young,

In its midst the maid Lilith built her house —

The always laughing, always rejoicing maid,

The maid Inanna — how she weeps!

As light broke, as the horizon brightened,

As Utu came forth from the "princely field,"

His sister, the holy Inanna,

Says to her brother Utu:

"My brother, after in days of yore the fates had been decreed,

After abundance had sated the land,

After An had carried off heaven,

After Enlil had carried off earth,

After Ereshkigal had been carried off into the nether world as its prize —

After he had set sail, after he had set sail,

After the father had set sail for the nether world,

Against the king, the small were hurled,

Against Enki, the large were hurled,

Its small stones of the hand,

Its large stones of the dancing reeds,

The keel of Enki's boat,

Overwhelm in battle like an attacking storm,

Against the king, the water at the head of the boat,

Devours like a wolf,

Against Enki, the water at the rear of the boat,

Strikes down like a lion.

Her brother, the hero Gilgamesh,

Stood by her in this matter,

He donned armor weighing fifty minas about his waist —

Fifty minas were handled by him like thirty shekels —

His "ax of the road" —

Seven talents and seven minas — he took in his hand,

At its roots he struck down the snake who knows no charm,

In its crown the Imdugud-bird took its young, climbed to the mountains,

In its midst the maid Lilith tore down her house, fled to the wastes.

The tree — he plucked at its roots, tore at its crown,

The sons of the city who accompanied him cut off its branches,

He gives it to holy Inanna for her throne,

Gives it to her for her bed,

She fashions its roots into a pukku for him,

Fashions its crown into a mikku for him.

The summoning pukku — in street and lane he made the pukku resound,

The loud drumming — in street and lane he made the drumming resound,

The young men of the city, summoned by the pukku —

Bitterness and woe — he is the affliction of their widows,

"O my mate, O my spouse," they lament,

Who had a mother — she brings bread to her son,

Who had a sister — she brings water to her brother.

After the evening star had disappeared,

And he had marked the places where his pukku had been,

He carried the pukku before him, brought it to his house,

At dawn in the places he had marked — bitterness and woe!

Captives! Dead! Widows!

Because of the cry of the young maidens,

His pukku and mikku fell into the "great dwelling,"

He put in his hand, could not reach them,

Put in his foot, could not reach them,

He sat down at the great gate ganzir, the "eye" of the nether world,

Gilgamesh wept, his face turns pale . . . .

Hullupu Tree: Version Two

Inanna and the Hullupu Tree

In the first days, in the very first days,

In the first nights, in the very first nights,

In the first years, in the very first years,

In the first days when everything needed was brought into being,

In the first days when everything needed was properly nourished,

When bread was baked in the shrines of the land,

And bread was tasted in the homes of the land,

When heaven had moved away from earth,

And the earth had seperated from heaven,

And the name of man was fixed;

[Source: Wolkstein, Diane & Samuel Noah Kramer. (1983). Inanna queen of

heaven and earth: Her stories and hymns from Sumer. New York: Harper & Row.

When the Sky God, An, had carried off the heavens,

And the Air God, Enlil, had carried off the earth,

When the Queen of the Great Below, Ereshkigal, was given

the underworld for her domain,

He set sail; the Father set sail,

Enki, the God of Wisdom, set sail for the underworld.

Small windstones were tossed up against him;

Large hailstones were hurled up against him;

Like onrushing turtles,

They charged the keel of Enki's boat.

The waters of the sea devoured the bow of his boat like wolves;

The waters of the sea struck the stern of his boat like lions.

At that time, a tree, a single tree, a huluppu-tree (Willow)

Was planted by the banks of the Euphrates.

The tree was nurtured by the waters of the Euphrates.

The whirling South Wind arose, pulling at its roots

And ripping at its branches

Until the waters of the Euphrates carried it away.

A woman who walked in fear of the word of the Sky God, An,

Who walked in fear of the Air God, Enlil,

Plucked the tree from the river and spoke:

"I shall bring this tree to Uruk.

I shall plant this tree in my holy garden."

Inanna cared for the tree with her hand

She settled the earth around the tree with her foot

She wondered:

"How long will it be until I have a shining throne to sit upon?

How Long will it be until I have a shining bed to lie upon?"

The years passed; five years, and then ten years.

The tree grew thick,

But its bark did not split.

Then the serpent who could not be charmed

Made it's nest in the roots of the huluppu-tree.

The Anzu-bird set its you in the branches of the tree.

And the dark maid Lilith built her home in the trunk.

The young woman who loved to laugh wept.

How Inanna wept!

(Yet they would not leave her tree.)

As the birds began to sing at the coming of the dawn,

The sun God, Utu, left his royal bedchamber.

Inanna called to her brother Utu, saying:

"O Utu, in the days when the fates were decreed,

When abudance overflowed in the land,

When the Sky God took the heavens and the Air God the earth,

When Ereshkigal was given the Great Below for her domain,

The God of Wisdom, Father Enki, set sail for the underworld,

And the underworld rose up and attacked him....

At that time, a tree, a single tree, the huluppa-tree

Was planted by the banks of the Euphrates.

The South Wind pulled at its roots and ripped its branches

Until the water of the Euphrates carried it away.

I plucked the tree from the river;

I brought it to my holy garden.

I tended the tree, waiting for my shining throne and bed.

Then a serpent who could not be charmed

Made its nest in the roots of the tree,

The Anzu-bird set his young in the branches of the tree,

And the dark maid Lilith built her home in the trunk.

I wept.

How I wept!

(Yet they would not leave my tree."

Utu, the valiant warrior, Utu,

Would not help his sister, Inanna.

As the birds befan to sing at the coming of the second dawn,

Inanna called to her brother Gilgamesh, saying:

"O Gilgamesh, in the days when the fates were decreed,

When abundance overflowed in Sumer,

When the Sky God had taken the heavens and the Air God

the earth,

When Ereshkigal was given the Great Below for her domain,

The God of Wisdom, Father Enki, set sail for the

underworld,

And the underworld rose up and attacked him.

At that time, a tree, a single tree, a huluppu-tree

Was planted by the banks of the Euphrates.

The South Wind pulled at its roots adn ripped at its

branches

Until the waters of the Euphrates carried it away.

I plucked the tree from the river;

I brought it to my holy garden.

I tended the tree, waiting for my shining throne and bed.

Then a serpent who could not be charmed

Made its nest in the roots of the tree,

The Anzu-bird set his young in the branches of the tree,

And the dark maid Lilith built her home in the trunk.

I wept.

How I wept!

(Yet they would not leave my tree.)"

Gilgamesh, the valiant warrior Gilgamesh,

The hero of Uruk, stood by Inanna.

Gilgamesh fastened his armor of fifty minas around his chest.

The fifty minas weighed as little to him as fifty feathers.

He lifted his bronze ax, the ax of the road,

Weighing seven talents and seven minas, to his shoulder.

He entered Inanna's holy garden.

Gilgamesh struck the serpent who could not be charmed.

The Anzu-bird flew with his young to the mountains;

And Lilith smashed her home and fled to the wild, uninhabited

places.

Gilgamesh then loosened the roots of the huluppa-tree;

And the sons of the city, who accompanied him, cut off the

branches.

From the trunk of the tree he carved a throne for his holy

sister.

From the trunk of the tree Gilgamesh carved a bed for Inanna.

From the roots of the tree she fashioned a pukku for her brother.

From the crown of the tree Inanna fashioned a mikku for Gilgamesh

the hero of Uruk.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024