Home | Category: Jewish Marriage and Family

JEWISH MARRIAGE

Jewish wedding in Aleppo in 1914 Marriage and wedding customs and traditions vary to some degree in accordance with the country of origin and the degree in which the couple is Orthodox or Reform however there are many common elements regardless of the couple’s background. Orthodox Jews usually marry within the Orthodox Jewish community

Although the Bible sanctions polygamy, the ideal marriage, as projected by the story of Adam and Eve, is monogamous. Divorce is permitted by Jewish law, although a rabbinical court sanctions divorce only if it is convinced that the breakdown in the marriage is beyond repair. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Caroline Westbrook wrote for SomethingJewish.co.uk: A Jewish marriage “is one of the cornerstones of the Jewish life cycle and as with all religions, is a great cause for celebration. In the past, it was common for Jewish marriages to be arranged by the parents, with the help of a match-maker, known as a Yenta, and some ultra-Orthodox communities still follow this practice today. Even though the union was arranged, the man still had to ask the father of the bride-to-be for his daughter's hand." [Source: Caroline Westbrook, SomethingJewish.co.uk, July 24, 2009, BBC]

Endogamy refers to marriage within a tribe or clan group, and exogamy refers to the practice of marrying outside of the tribe, kingroup, or clan. Endogamy is often the preferred or accepted practice. Orthodox Jewss usually marry within the Orthodox Jewish community. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004]

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; BBC - Religion: Judaism bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism ; Encyclopædia Britannica, britannica.com/topic/Judaism; Yivo Institute of Jewish Research yivoinstitute.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Aish.com aish.com ; Jewish Museum London jewishmuseum.org.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Holy Intimacy: The Heart and Soul of Jewish Marriage” by Sara Morozow and Rivkah Slonim Amazon.com ;

“Jewish Marriage: How to Achieve the Ideal Marital Relationship” by Yosef Malka Amazon.com ;

“The Jewish Wedding Now” by Anita Diamant Amazon.com ;

“The Jewish Wedding Companion” (complete liturgy and explanations) by Rabbi Zalman Goldstein Amazon.com ;

“Choosing a Jewish Life, Revised and Updated: A Handbook for People Converting to Judaism and for Their Family and Friends” by Anita Diamant, Barrie Kreinik, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Living a Jewish Life: Jewish Traditions, Customs, and Values for Today's Families” by Anita Diamant, Howard Cooper, et al. Amazon.com ;

“To Be a Jew Today: A New Guide to God, Israel, and the Jewish People”

by Noah Feldman Amazon.com ;

“Essential Judaism: Updated Edition: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs & Rituals”

by George Robinson Amazon.com ;

“Living Judaism: The Complete Guide to Jewish Belief, Tradition, and Practice”

by Wayne D. Dosick Amazon.com ;

“Judaism: History, Belief and Practice” by Dan Cohn-Sherbok Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com

Views of Love and Marriage in Judaism

According to “Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia”: Romantic love and attraction are a main theme of the Song of Songs in the Bible, but Jewish marriage is based on more than that. Marriage involves a binding, legal relationship between a man and a woman, freely entered into by both sides and witnessed, supported, and underwritten by the authority of God, the community, and the religion. It is at the same time a union of two houses and two families, as well as an act of the community by which it fulfills a divine mitzvah and ensures its own eternity. [Source:“Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia”, Erwin J. Haeberle, Vern L. Bullough and Bonnie Bullough, eds., sexarchive.info]

That is a lot of weight, and the ceremonies attendant on a Jewish wedding reflect a great deal of solemnity together with boundless, irrepressible joy. It has even been taught that at a wedding, one is permitted to celebrate to excess, which for some may mean to become intoxicated. If such a thing is done to add joy to the wedding feast, it might even be considered a mitzvah. Classically, there are three ways to consecrate a marriage, any one of which has been sufficient. In a modern Jewish marriage, at least in the Orthodox Ashkenazi rites, all three are often included. These are keseph, shetar, and bi'ah.

Keseph, "silver," is the giving of something of value by the groom to the bride, as a way of sealing a legal contract, with the intention of concluding a contract of marriage. Typically, it is a plain gold ring, gold because it has recognizable value, and plain because the value of fancy artwork would be hard to assess in a way that gold itself is not. A coin of great value would do as well, however. All the later interpretations of the meaning of the plain gold ring, such as that its endless circularity points to infinite love, must be considered inspiring and valuable homilies. In many modern Jewish weddings, rings are exchanged, which raises a question of whether there has actually been any giving at all. That question, for those who are troubled by it, can be resolved by the groom's paying for both rings. This gift is a legal transaction and must be witnessed.

Shetar, "contract," is the ritual signing before witnesses of a formal, legal contract, the wedding ketuvah. Such ketuvot are often decorated with beautiful artwork and displayed prominently in the new home. The traditional text of the ketuvah is in Aramaic, a near relative of Hebrew and the onetime colloquial language of the common people of Israel. It guarantees the woman her marital rights, including her sexual rights and her rights to adequate new clothing, cosmetics, and support. It details exactly what she is bringing into the marriage: money, sheets, blankets, all her property, and so on. Her husband is responsible for all of that, and in the event the marriage fails, he is held accountable for it. The document is quite one-sided; it is there as an instrument of the court to protect the woman, not the man. In Orthodox, Conservative, and some Reform weddings, it is read out, affirmed, and signed freely and willingly by both bride and groom in the presence of two disinterested witnesses as part of the wedding ceremony. A number of modern ketuvot have substituted more romantic language for the traditional text, and some have tried to make the document more two-sided. In divorce cases, the ketuvah has been considered a binding instrument in some civil courts, and its provisions have sometimes been enforced by the civil authorities.

Bi'ah, "intercourse," is a formal part of Orthodox, some Conservative, and (rarely) Reform weddings. The couple is sequestered in a private room for a period, and that sequestering is duly witnessed. This presumptive intercourse must be for the purpose and with the intention of creating a valid marriage. In other words, mere sex without the intention to consummate a marriage does not create a marriage.

Duty of Marriage in Judaism

Marriage is one of the most important Jewish acts because it fulfills a command by God in “Genesis” "to bear fruit and multiply." Marriage is regarded as the cornerstone of both family and community life. Celibacy is considered unnatural. Rabbis marry and unions between cousins and uncles and nieces are permitted.

As rabbis have observed, the first commandment issued by God was addressed to Adam and Eve: "Be fruitful and multiply …" (Gen. 1:28). But God created Eve as Adam's companion, not only as a partner for procreation. Male and female are bonded in companionship in order to create a family, to become husband and wife as well as father and mother to their common offspring. Marriage is thus regarded as a covenant. Indeed, the union of man and wife often serves as a metaphor for the relationship between God and Israel. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

The Judea-Christian-Islamic tradition places great significance n marriage and give it high symbolic value. Marriage is not meant to be taken lightly and breaking up a marriage is regarded as something that must be avoided at all costs. By contrast in some societies (mostly small isolated communities) men and men simply live together, and no great fanfare is made about their union.

George P. Monger wrote in “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ Continuity of the tribe or family has been very important to Jewish people everywhere, and the choice of a marriage partner for a young man has often been arranged by a go-between — usually a rabbi. Rabbis were asked for their help because of their knowledge of the families and tribes. A donation to the synagogue was often made for this help. In time, the professional matchmaker, the shadchan, came into being who would be commissioned to find a wife for a young man. The shadchan would extol the virtues of a prospective bride to the young man and arrange the contracts. It was customary for the bride and groom to not see each other before the wedding day, and if the wedding was arranged by a matchmaker, the couple may have seen very little of each other. Certainly they would not have been able to get to know each other. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

History of Marriage Among the Jews

The oldest known marriage certificate was a Jewish one, dated to the 5th century B.C., found at the Jewish garrison off Elephantine in Egypt. It was a contract for an exchange of six cows for a 14-year-old girl. A revised marriage law adopted in the 1st century A.D. is virtually the same as the one used today. In the 17th century marriage rings featured a small house-shaped bezel, where a tiny Torah was stored.

George P. Monger wrote: “It is said that the Jewish nation has the oldest recorded rites of marrying because of accounts in the Bible of Adam and Eve as the first “married” couple. However, there are no descriptions of marriage in the Old Testament, except for the story of Laban marrying his eldest daughter Leah to Jacob, instead of Rachel, his youngest, as promised. When Jacob found that he had been fooled, Laban said, “Finish this daughter’s bridal week: then we will give you the younger one also, in return for another seven year’s work” (Gen. 29.27). This suggests that the early Jewish wedding involved a celebration lasting a whole week. In justifying his deceit, Laban said, “It is not our custom here to give the younger daughter in marriage before the older one” (Gen. 29.26–27).

Jewish marriage has traditionally been monogamous but the ancient Hebrews were both monogamists and polygamists and had laws that required men to marry the their brother’s widow if the dead brother had no son. Abraham, Moses and David all had more than one wife. Solomon reportedly had 700 wives and 300 concubines. The taking of concubines was practiced by the Jewish “nobility”

In Israel, the median age of marriage in 1986 for Jewish men was 26.4, for women 23.1. Many men deferred marriage until after their mandatory service in the Israel Defense Forces. The age at marriage was considerably younger among ultra-Orthodox Jews, who were effectively exempted from army service, and for whom the biblical injunction to "be fruitful and multiply" is very important. [Source: Encyclopedia of World Cultures]

Types of Jewish Marriage

Jewish wedding ring Since it is regarded as a bad thing for a Jew to marry a non Jew, a great efforts has been traditionally made to find a marriage partner for a young man or woman within the Jewish community. In the old days, matchmakers known as “shiddach” were hired.

According to Jewish law uncles may marry nieces but aunts may not marry nephews. Marriage to all four first cousin types is permitted. Unlike, a Muslim a Jewish man can remarry his former wife if she had not married another man before the remarriage. Levirate marriages in which a widow married her husband's brother is an old tradition. It was developed to make sure the widow was looked after. In the “halizah” ritual the brother can be discharged from his duty if the widow removes his shoe.

George P. Monger wrote in “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “According to a passage in the Old Testament of the Bible, in Deuteronomy (25. 4–10), a man was dutybound to marry his brother’s widow if the brother died without fathering any children. It was the man’s duty to father a child with the woman to carry on the brother’s name. If he were to reject her he would be publicly shamed: Then shall his brother’s wife come unto him in the presence of the elders, and loose his shoe from off his foot, and spit in his face, and shall answer and say, So shall it be done unto that man that will not build up his brother’s house. And his name shall be called in Israel, The house of him that hath his shoe loosed. Today, in Jewish tradition, a man is under less of an obligation and can forego this right and obligation. However, some men have taken advantage of this and forfeited their right on receipt of a cash payment from the widow. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

Polygamy and Concubines in Judaism

Some of the Old Testament’s greatest figures either slept with someone other than their wives or had multiple wives, Abraham slept with with his wife’s servant after discovering that his wife was infertile and Jacob fathered children with four different women (two sisters and their servants). David, Solomon and the kings of Judah and Israel were all polygamists. King Solomon in the Bible was said to have had “seven hundred wives, princesses, and three hundred concubines” (1 Kings 11.3).

Polygamy is permitted in Judaism but is restricted by clauses in the marriage contract and has traditionally been very rare. In the old days polygamy was practiced in some Jewish communities. The Tunisian Jews in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries practiced polygamy if the first wife was unable to have children. In Syria, men were allowed to look for a new wife if their first one failed to produce a child in ten years. If you go back to ancient times, there was little difference between a wife and a concubine; among the Hebrews. A concubine who lived in a man’s house continuously for three years became his wife.

Although the Bible sanctions polygamy, the ideal marriage, as projected by the story of Adam and Eve, is monogamous. The practice of having more than one wife persisted, however, until the German Rabbenu (Our Rabbi) Gershom ben Judah (960–1028 A.D.) proclaimed a ban on such marriages, which has been universally honored since by Ashkenazi Jews. Today Sephardic Jews also reject polygamy. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Mixed Marriages

Rabbis have traditionally warned Jews not to marry outside their faith. Finding rabbis to marry mixed couples used to be difficult — most Orthodox rabbis still refuse to conduct the wedding ceremonies — and Jewish parents literally donned morning clothes if their child married a gentile. These days mixed marriages are more accepted and even Orthodox rabbis unwilling to perform marriage ceremony will refer couples to a rabbi who will.

About one third of European Jews and half of American Jews marry non-Jewish spouses. Only about a forth of interfaith couples raise their children as Jews. Couples that try to raise their children with two faiths find that the children get confused.

One man, who had married a non-Jew, told the Independence, "I visited the synagogue quite frequently, and I was going to touch the Torah during a service. But then someone whispered in the ear of the rabbi, and was stopped and they told me, 'You're not married within the faith, you can't go tot he Torah,' Within seconds I was reduced to a persona non grata in the synagogue, and didn't feel like going there again."

A non-Jewish women who married to Jewish man said her children can light candles, attend religious classes but are not allowed to bless the Torah during rituals such as bar mitzvahs.

Shadchan (Jewish Matchmakers)

Wedding Chupah A marriage broker called a shadchan or yenta was traditionally an essential part of a Jewish marriage. The profession was made famous with a song from "Fiddler on the Roof". Traditionally, in Russia, Jewish marriages were arranged by matchmakers and separate rituals took place at the bride’s and groom’s houses. In Central Asia and parts of Russia, marriages were often arranged when the bride and groom were quite young. Matchmakers hired by the groom’s father searched for prospective brides. When one was found a bride price was offered, and a ceremonial betrothal meeting took place between the bride’s and groom’s family. At this meeting, the bride unveiled her face and bride and groom laid eyes on one another for the first time.

George P. Monger wrote : “Originally he would have been the head of a school established to keep alive and develop Judaism after the destruction of the second temple in 70 A.D. As a leader in the community and knowledgeable in religious and legal matters, he would know the families in the vicinity and their circumstances and would have been approached for his help and advice concerning who should marry whom. The fathers of the couple would express their gratitude by making a donation to the school. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

Rabbis were also approached for their help and advice, and again donations would be made to the synagogue for the service rendered. In time, the shadchan became more like a traveling peddler. This person would often be not very successful as a rabbi or be one holding only a minor post in the synagogue. With a good knowledge of religious observance and custom, he would be welcome in any Jewish home and would arrange marriages on a commission of 2 or 3 percent of the dowry, depending on the amount of travel involved.

Not surprisingly, since the shadchan worked by commission and was paid upon a successful marriage, there are stories of the overselling of the attributes of each of the couple. Lane (1836), in a nineteenth-century description of life in Egypt, related how the mother of a young man who wishes to marry may employ one or more matchmakers, known as a khát’beh or khátibeh, who would report back on the girls available, describing their looks and attributes. The man’s mother and other female relatives would help in the choice of bride. Once a choice was made, the khát’beh would take a present from the young man to the girl’s family and extol his virtues to the girl. The matchmaking tradition still exists in parts of Ireland, notably the rural areas where the population is scattered and it is difficult to meet members of the opposite sex.

Jewish Marriage Contract

As is true with a Christian marriage, a Jewish marriage is a legal contract entered willingly by the bride and groom and validated by witnesses. The Ketuhah is the traditional marriage contract. According to Jewish law, a couple may not live together until the Ketubah is drawn up and signed by witnesses who have traditionally put their names on the document after the bride’s family passes a kerchief to the groom’s family.

The Ketubah is often a richly decorated document with a text written in Aramaic. It states the husband’s obligation to his wife according to the codes of Jewish law and regulations in the Talmud. The provisions are binding and are set up as protection for the wife. Among other things it provides for the repayment of the bride price in the event of a divorce of death. In the wedding, the ketubah, is often read out loud (usually in Aramaic and with a translation into the language of the couple being married).

Monger wrote: In the Jewish wedding ceremony, the reading and the signing of the ketubah (or ketubbah), the marriage contract, is an important part of the ceremony. The groom has to read and accept the terms of the ketubah, which gives details of the duties and responsibilities of the Jewish husband — notably to provide food, clothing, and conjugal rights. However, it also details the settlement that the husband will give his wife in the event of him divorcing her (a previously married woman would receive half the amount that would be paid to a virgin). [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004]

The ketubah may additionally list the dowry that the bride brings with her. He is responsible to her and her heirs for the maintenance of this dowry, and he may match the value of the dowry with a personal payment to his new wife. The ketubah is read out to the bride, usually in Aramaic, and then witnessed. Today, many of these ketubahs conform to a standard text and are often read out in a cursory manner, partly because the settlement in the event of the man divorcing the woman is at the heart of the contract and is a little sensitive to be read out beneath the wedding canopy.

There are extant ketubah texts from as early as the fifth century B.C., which show how Jewish tradition has changed. These texts, from Elephantine, an island in the River Nile where Jewish mercenaries in the pay of the Persian emperor lived, have clauses detailing the penalties incurred by the person within the marriage who initiates a divorce — that is, either the husband or the wife could initiate the divorce. In later Jewish law it was considered impossible for the woman to divorce her husband.

Jewish Divorce

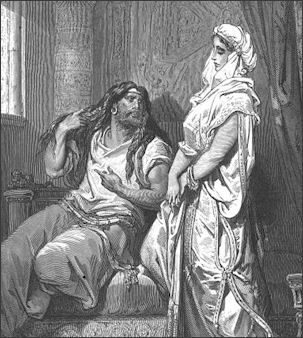

Samson and Delilah Divorce is permitted by Jewish law, although a rabbinical court sanctions divorce only if it is convinced that the breakdown in the marriage is beyond repair. Divorce is viewed by Jews as a last resort ("even the altar sheds tears" the Talmud reads when it happens). Jewish marriages may be dissolved in a witnessed procedure when the husband gives the wife a document that says she is free to marry another.

Complicated rules govern divorce. A ge , or bill of divorce, has to be drawn up by a recognized scholar. Reform rabbis, however, accept a civil divorce as terminating a Jewish marriage. According to Jewish law, a divorce can only take place with permission of the husband. This creates problems if a husband disappears or refuses to grant permission for a divorce. Before the Ten Commandments a man could get a divorce and throw his wife out on the street if he found "some uncleanness in her,” telling her "You are no longer my wife" before two witnesses. Rabbis have traditionally been prohibited from marrying divorcees or proselytes.

Jewish women do not enjoy the same rights as Jewish men when it comes to divorce but certain laws are have been written to protect them. In some countries Jewish women can easily get a civil divorce but are denied a religious one. If a divorced woman gets remarried and has children, ancient Jewish laws recognize these children as “mamzer.” In Britain, a Jewish women once got even with a husband who refused to grant her a divorce by invoking an old Jewish law, called “nidui” , which prevents any observant Jew from speaking to the husband or going within six meters of him.

Monger wrote: “The marriage contract, the ketubah, includes details of the settlement that the husband would give his wife in the event of him divorcing her (a previously married woman would receive half the amount that would be paid to a virgin). However, in Jewish divorce, although the couple can obtain a legal divorce in the civil courts, which is binding and does separate the couple, the ex-husband and exwife also need to grant each other a religious divorce known as a get. If this is not granted, then the spouse is “chained.” [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004]

Views on Divorce in Judaism

According to “Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia”: In a traditional Jewish marriage, the woman's rights are protected by the ketuvah. In case of a divorce, the burden of fulfilling the ketuvah falls on the husband. Grounds for a divorce are the subject of considerable debate in the Talmud. The House or School of Hillel took the position that, although divorce should be prevented by any means practicable, if it developed that the marriage was hopeless, then any excuse to dissolve the formality was acceptable. This view was embodied in Talmudic idiom by the expression that even if she burned a dish, if it was done with agreement and intention, it could be grounds for divorce. The House of Shammai took the strict view that grounds for divorce should be highly limited. The Sanhedrin majority went with Hillel. [Source: “Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia”, Erwin J. Haeberle, Vern L. Bullough and Bonnie Bullough]

Nonetheless, divorce is looked on as a tragedy and a failure. God is pictured as crying for the pain that a divorce involves, and saving a marriage is considered a great mitzvah. The instrument of religious divorce is called a get, "bill of divorcement," and is issued to the wife by the husband or by the court on his behalf. She retains custody of it or of a substitute document that testifies to its existence. This is because biblical law would at one time have allowed a husband to take another wife while still married, but not a woman to take another husband. She, therefore, has a greater need to prove herself free to marry. If the husband does not choose to give the wife a get, the court may compel him or act in his behalf, but among the Orthodox the courts often choose to do nothing. This inaction may cause great hardship for the woman and may even make her vulnerable to a kind of blackmail. Further, if a husband abandons a wife and disappears without a trace, there is no provision in Jewish law to presume his death after some years of absence. The wife is regarded as an abandoned married woman, not as a divorced woman, unless someone comes forward to say that the man's death has been witnessed. If she remarries and he reappears, she is ipso facto an unintentional adulteress and her second marriage is invalid. The potential for abuse is obvious, but fortunately it rarely occurs.

The Reform or Liberal Jews have in most cases dispensed with the get, partly to avoid the abuses it allows and partly because, in the presence of civil divorce, they feel they can perform a remarriage without requiring evidence of a religious divorce. From an Orthodox point of view, such a remarriage without a prior get might be invalid. The Conservatives still use the get but do so most effectively as a way of getting the couple into counseling; they avoid abuses by empowering the court to act in behalf of the husband if necessary.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, Library of Congress, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024