Home | Category: Rabbis, Synagogues and Prayers

RABBIS

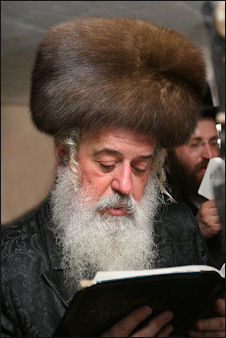

Rabbi Moshe Leib Rabinovich Originally theocratic, Judaism has evolved a congregational policy. The basic institution is the local synagogue, which is operated by the congregation and led by a rabbi of their choice. Rabbis (meaning "teachers") are regarded as learned persons, interpreters of religious doctrine, arbiters of law and custom as well as leaders of synagogues and religious activities. Each rabbi is bonded to the community he serves. Generally only men serve as rabbis.

Rabbis are not like priests. They have no ecclesiastical authority; services can be conducted without them and generally they are not part of a religious hierarchy. Any Jew with knowledge of prayers and laws can lead services, perform marriages or bury the dead, although rabbis usually do preside over these activities.

The creation of Judaism was the work of rabbis who reconstructed the religion of the Jews by interpreting the Torah in a world without a Temple based on oral traditions, around families and synagogues. The written work of these rabbis formed the basis for the Mishna and the Talmud.

Rabbis have traditionally been more like lawyers and scholars that priests. In Israel the chief rabbis have civil authority in family law. In most other places decisions made rabbis are not legally binding or have semi-legal status.

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; BBC - Religion: Judaism bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism ; Encyclopædia Britannica, britannica.com/topic/Judaism; Yivo Institute of Jewish Research yivoinstitute.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Aish.com aish.com ; Jewish Museum London jewishmuseum.org.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Einstein and the Rabbi: Searching for the Soul” by Rabbi Naomi Levy Amazon.com ;

“Rebbe: The Life and Teachings of Menachem M. Schneerson, the Most Influential Rabbi in Modern History” by Joseph Telushkin, Rich Topol, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Pearls of Wisdom from Rabbi Yehonatan Eybeshitz: Torah Giant, Preacher & Kabbalist by Rabbi Yehonatan Eybeshitz and Rabbi Yacov Barber Amazon.com ;

“Essential Judaism: Updated Edition: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs & Rituals”

by George Robinson Amazon.com ;

“Guide for the Perplexed” by Moses Maimonides, Andrea Giordani, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Living Judaism: The Complete Guide to Jewish Belief, Tradition, and Practice”

by Wayne D. Dosick Amazon.com ;

“Judaism: History, Belief and Practice” by Dan Cohn-Sherbok Amazon.com ;

“The Transformation of Israelite Religion to Rabbinic Judaism” by Juan Marcos Bejarano Gutierrez Amazon.com ;

“Understanding Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism” by Lawrence H. Schiffman , Jon Bloomberg, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Living a Jewish Life: Jewish Traditions, Customs, and Values for Today's Families” by Anita Diamant, Howard Cooper, et al. Amazon.com ;

“To Be a Jew Today: A New Guide to God, Israel, and the Jewish People”

by Noah Feldman Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com

Spiritual Leaders in Judaism — Priests, Prophets and Sages

In ancient times, Jewish religious activity revolved around the Temple. The rituals and sacrifices held there were led by a caste of priests not rabbis. After the Temple was destroyed in A.D. 70 and Jewish people were dispersed around the world, the priestly caste was made obsolete. Judaism went through a lot of changes; it became more democratic. Religious life became centered around local synagogues instead the Temple and activities at them were run by rabbis.

The Bible mentions different kinds of spiritual leaders: 1) Priest (kohen) who served in the Temple and were the custodian of the law (Lev. 21; 22:1–25; Deut. 17:8–13); 2) Prophets (navi) who brought a particular message from God to the people (Deut. 18:18; i Sam. 9:9); and 3) Sages (akham), teachers of worldly wisdom and good conduct (Jer. 9:22; Eccles. 7:4–5). [Source: Louis Jacobs, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 1990s, Encyclopedia.com]

In ancient times, religious activity was centered around the Temple and overseen by a priestly caste rather than rabbis. These priests made offerings, cured the sick, and perhaps acted as judges. At the Temple they lighted incense on altars and presided over daily, weekly and animal sacrifices. The priestly caste also butchered the meat after the animal sacrifices and had a monopoly over its distribution. By the time of Christ the priests charged people money to ritually slaughter their animals. Moneychangers at the temples helped pilgrims use the right coinage to pay for the sacrifices. After the destruction of the Temple in A.D 70 the priestly caste lost their jobs and their role in religious life was replaced by rabbis.

Lack Organizational Leadership in Judaism

Paul Mendes-Flohr wrote in the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: Since the abolishing of the Sanhedrin at the beginning of the fifth century A.D. and the decline of the office of the geonim, the heads of the Babylonian rabbinical academies, in the eleventh century, Judaism has not had a central religious authority acknowledged by all communities. In response some communities have organized themselves around a regional or countrywide leadership, such as a central rabbinical judicial court or even a chief rabbi. In fifteenth-century Turkey, for instance, the position of hakham bashi (chief sage) was established. In the nineteenth century the position was elevated by the Turkish authorities and assigned the function of chief rabbi of the Ottoman Empire. [Source:Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

In 1807 Napoleon Bonaparte convened what he ceremoniously called a Sanhedrin in order to gain rabbinical sanction for the changes in Jewish laws and theological orientation that he deemed would facilitate Jewish integration into the French state. Napoleon hoped that this body of representatives, two-thirds rabbis and one-third lay leaders from the French empire and the Kingdom of Italy, would gain the recognition of all Jewry. The world Jewish community greeted the French Sanhedrin with indifference or profound suspicion, however, and after doing the emperor's bidding, it ceased to exist. Thereafter, Napoleon instituted the office of a chief rabbi, which eventually was transferred from government auspices to the autonomous communal organization of French Jewry.

A chief rabbinate in England arose at the beginning of the nineteenth century and was officially recognized by the government in 1845, which assured that its authority would extend over the entire British Empire. In 1840, during the period of Ottoman rule, Jerusalem became a regional administrative center, and the hakham bashi or rishon le-Zion (First of Zion, or the chief rabbi of the Sephardic community) was recognized as the chief rabbi of the Land of Israel. In 1920 the British mandatory government of Palestine established two offices of the chief rabbinate, one for the Ashkenazim and the other for the Sephardim. The authority of these offices, which the State of Israel continues to support, is not universally acknowledged by all Jewish communities, however. Recurrent attempts to establish a chief rabbinate in the United States have failed. Instead, each denomination — Orthodox, Reform, Conservative, and Reconstructionist — has established its own organization.

Cohanim

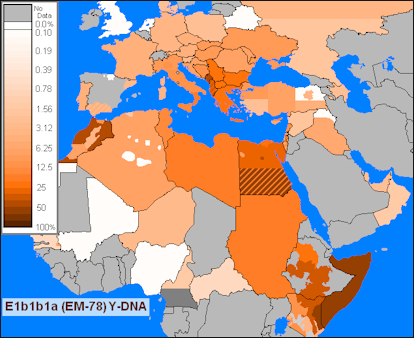

distribution of Y Haplogroup EM-78, the Cohanim marker “Cohanim” are members of priestly clan that trace their paternal lineage back to the original cohen, Aaron, the brother of Moses and a high Jewish priest. Cohanim have certain duties and restrictions. According to ancient Jewish rituals the redemption of the firstborn son requires payment to a Cohen. Only the Cohanim in prayer shawls are allowed to bless suppliants at Jerusalem’s Western Wall. This is an inherited duty.

Cynics have long wondered if such a diverse looking group of people could all be descendants of the same person, Aaron. Dr. Karl Skorecki, a Jew from a Cohan family, and geneticist Michael Hammer at the University of Arizona found genetic markers on the Y chromosome among Cohanim that appear to have been passed down through a common male ancestor for 84 to 130 generations, which goes back more than 3,000 years, roughly the time of Exodus and Aaron.

The marker is found in half of the Cohanim studied in both Ashkenazi and Sephardic communities and among Jews of European ancestry and African ancestry. Some members of the Lembaa, a South African tribe that claims to be a Lost Tribe of Israel, also have the genetic Cohan marker. The marker as also been found in some Christians that have no knowledge of any Jewish ancestry. Genetic research also found that 40 percent of Ashkenazi Jews descend from just four women.

Levites are another hereditary priesthood passed from father to son. They are said to have descended from Levi, the third son of the patriarch Jacob. Levites and Cohanin were important in ancient Israel, but sometime between 200 B.C. and A.D. 500 their duties were taken over by rabbis and Jewish status became defined by maternal descent. Genetic studied of Levite show more of a mixed ancestry than that of Cohanm.

History and Evolution of Rabbinical Learning

Jacob Kat wrote in the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences: Besides emphasizing the practical need for knowledge of the law (Torah) as a guide to religious observance and communal practice, Rabbinic Judaism regards the study of the law as an end in itself and one of the most basic of religious duties. Therefore, it advocates the dedication of one’s time to the study of the Torah and exclusive devotion to it, even at the cost of reducing all other activities to a bare minimum. [Source: Jacob Kat, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, Encyclopedia.com]

Since early Pharisaic times there developed an elite which tried to live up to these demands. This was first achieved by the leading of an austere and even ascetic life in a society of peasants or artisans where work could be limited to provide for the necessities of life. In Mishnaic and Talmudic times, both direct and indirect support were provided by the community to members of the learned elite. They were often exempted from taxation and given certain minor business concessions: where they were concentrated in academies, as in Babylonia during Talmudic times, for example, these institutions were supported by voluntary contributions, and in the early Middle Ages a tax was levied on the Jews within their districts. Generally, despite variations arising from the different environments in which they existed, all Jewish communities followed these patterns. In the earliest stages of a Jewish settlement, men of learning were not to be found, but after having consolidated itself economically, a particular community usually attracted scholars from other, longer-established Jewish communities in the Diaspora.

The status of the elite varied according to prevailing economic conditions. In Yemen, where Jews remained an artisan class, no systematically supported elite developed and learning was cultivated as a part-time occupation of the intellectually oriented. In France and Germany, where the Jews became money lenders, their economic activity left much time free for independent study by “laymen,” alongside that taking place in the communally supported institutions devoted exclusively to the study of the texts and the training of young persons in their interpretation. In Muslim and Christian Spain the academies were supported by rich courtiers. In addition to the support of the very rich, the academies of Poland in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries could rely on the support of the less wealthy but still prosperous middle class. The intellectual elite became dependent upon the court Jews (the permanent financial agents of the abso-lute rulers of German principalities), who emerged in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In all periods there were instances of wealthy families supporting a scholar among their own kin and sometimes even sustaining a whole academy which had grown up around him.

The door to the intellectual elite was, both in principle and in the final analysis, open to all, though naturally the time required to master the complex data made it easier for the well-born and well-to-do to attain the necessary intellectual level. In several instances this conjunction of advantages, circumstances, and hereditary talent resulted in learned family dynasties.

Support and Authority of Rabbis

Jacob Kat wrote in the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences: The support of those who devoted themselves to study was regarded as one of the highest religious virtues. The contributor was viewed as participating vicariously in the activity of the learned. Even after the maintenance of scholars had become common, exceptional individuals still adhered to the old ideal and refused to accept any remuneration for their studies. Indeed, one of the greatest authorities of medieval Jewry, Maimonides (1135–1204), lodged a formal protest against the institution of private or communal support of the learned. For the average scholar, however, neither such protests nor his own qualms were of much avail, as both the changed economic conditions and the ever-increasing body of material to be mastered made full-time study imperative and necessitated what may be called a division of labor between the economically active and the learned. [Source: Jacob Kat, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, Encyclopedia.com]

The disapprobation which had adhered to the acceptance of payment by scholars had been attached also to the acceptance of payment for any services rendered in the exercise of religious authority. It was originally assumed that teaching, preaching, serving as a judge, or functioning in any other religious capacity was to be done gratuitously. Later, payment for such services was legalized and morally defended. When such functions were concentrated in the hands of one person, spontaneously by virtue of his intellectual and moral pre-eminence or formally by election by the community, the communal rabbinate arose. This occurred noticeably in Christian Spain in the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries and in Germany and Poland in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. In the course of time a fixed salary was guaranteed in addition to various emoluments.

Any action of a scholar or rabbi in matters of ritual or in the performance of marriage or divorce drew its authority from his halachic expertise. If an error could be shown, the action could be invalidated. As no formal hierarchy existed, invalidation could be achieved only by appeal to some informally acknowledged higher rabbinic authority or by bringing the matter before the assembled opinion of the learned. On all levels, once decisions were made, discussions were conducted upon formal legal categories. Although theoretically the validity of any act depended solely upon its technical agreement with an external frame of reference (halachah), in practice it drew much of its authority from the fact that it came from one who was regarded as being charismatic in consequence of his knowledge of and sustained contact with divine law and lore.

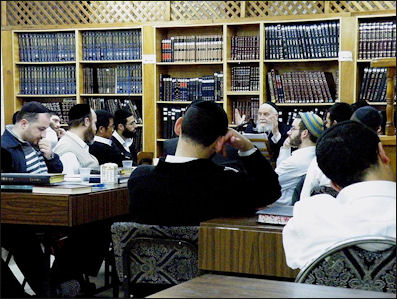

Rabbinic Debate and Study

Rabbi students at a Yeshiva The rabbinic model of study is the practice of seeking the relevance of passages from the Torah to contemporary issues. This form of study is often centered around discussion groups called “midrash” (from the Hebrew root “to search”).

Rabbis and future rabbis sit before the Torah ark swaying over a volume of the Talmud and debate Talmudic interpretations.

Yur Foreman, a professional light middleweight boxer who is studying to be an Orthodox rabbi told the New York Times that answering the rapid-fire questions from his teacher Rabbi DovBer Pinsom was tougher than his boxing training: “It’s a sharpen-your mind workout. When I go to the gym I am training my physical self. With the rabbi, I’m training my spiritual muscles.”

Seven year cycle of Talmud study.

Jewish Education

Jews put a strong emphasis on education and piety is equated with learning. Traditionally, literacy has been universal, among males, anyway, and schooling and study of the sacred texts began at a young age. In ancient times children on their first day of school were given sweets in the shape of letters so they would associate learning things that taste good.

The education of children is considered the primary responsibility of parents. The scriptures contains many references to this duty: “You shall teach them [the commandments] diligently to your children, and you shall talk to them when you sit on your house, and when you walk by the way and when you lie down, and when you rise.”

For children to grow up to be good Jews it considered essential that they learn by heart all 613 commandments in the Torah and be familiar with a variety of interpretation and opinions for each one.

In the old days boys were sent to schools to learn Hebrew, the Pentateuch, and the prayers, often by rote. Larger Jewish communities had advanced rabbinic schools, where the Talmud was taught. Girls were generally educated at home by their mothers.

Jewish Schools

Yeshiva in Belarus In the past Jewish children were taught at a school attached to the synagogue called a “cheder” . In Europe, many Jews attended secular schools. Western-style schools were introduced in the Middle East in the 19th century by Christian missionaries and the Alliance Israelite Universelle.

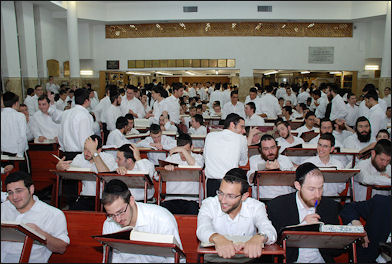

Yeshivas are Jewish religious high schools, which have traditionally concentrated on Talmudic study and accepted only boy students. In yeshivas boys have traditionally studied the Talmud in pairs, reading it carefully and then discussing it in Yiddish. Often the boys study little else other than religion.

For students that attend them, the Yeshiva marks the beginning of a lifetime spent studying Jewish texts. Some study Aramaic so they can read the Babylonian Talmud in the language it was written and continue their studies when they are well into their 20s. . Many students become rabbis, scribes or scholars.

At a typical ultra-Orthodox elementary school children spend five hours a day studying the Torah, which their teachers insist is all they need to know to get through life. They spend les than three hours day studying math, science, geography and nature and don’t spend any time studying literature or culture.

Why Do Jewish Parents Spend So Much Money on Education

Jack Wertheimer wrote in Commentary Magazine: “Why do parents spend these sums of money? For the same reason so many American parents expend staggering sums on college tuition: they believe they are getting value for their dollar. Immersive Jewish education may not provide the same kind of material payoff as a college diploma, but it greatly increases the chances of children learning the skills necessary for participation in religious life, living active Jewish lives, and identifying strongly with other Jews. Day-school tuition is the cost many parents believe they must bear if their children are to retain their heritage in a society that exerts enormous assimilatory pressures. [Source: Jack Wertheimer, commentarymagazine.com, March 1, 2010 ^|^]

Yeshiva Limud “They are right. It takes time and considerable effort to transmit a strong identification with the Jewish religion and people; to nurture a facility in the different registers of the Hebrew language: biblical, rabbinic, and modern; to teach young Jews the classical texts of their civilization; to expose them to Jewish music, dance, and art; and to socialize them to live as Jews—all the while providing a first-rate general education. Ample research has limned the association between the number of “contact hours” young people spend in Jewish educational settings and their later levels of engagement. Simply put, “more” makes a significant difference. It is not hard to find adult alumni of day schools, summer camps, and Israel programs who attest to the formative impact of their experiences. Not surprisingly, many parents committed to Jewish life want their children to enjoy the same benefits. ^|^

“Families recognize that they can no longer rely upon institutions that once had been central to the socialization of young Jews: most Jewish parents have neither the time nor, in many cases, the knowledge to transmit Jewish learning to their children; extended families are now widely dispersed, so they cannot play an active role; and few Jews reside any longer in densely populated Jewish neighborhoods, where in years past Jewish mores and customs were internalized through osmosis. Thus, conclude Carmel and Barry Chiswick, two authorities on the economics of Jewish life, “the formation of Jewish human capital must rely on a system of Jewish education.”“ ^|^

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except last picture, Times of Israel

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, Library of Congress, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024