Home | Category: Babylonians and Their Contemporaries / Neo-Babylonians / Art and Architecture

AKKADIAN AND OLD BABYLONIAN ART

.jpg)

Queen of the Night (Babylon) The Akkadians produced extraordinary bronze and copper sculptures. Among the treasures from the Akkadian Age at the Iraq National Museum: are the Akkadian Bassetki, a 150-kilogram copper statue of a man with his legs crossed, dated to 2300 B.C. Found in Nineveh, it is regarded as the one of the most important pieces in the museum and is prized because of its exquisite details. It contains inscriptions that proclaim the military victories of an Akkadian king. Although only the bottom half of the figure is intact its prized for its realism.

An ancient brass relief of the Akkadian ruler, King Naram-Sin, dated at 2350 B.C., is one of the earliest examples of an advanced form of bronze casting. Akkadian cylindrical stone seals depict deities in horned headdresses engaged in battle. A mold depicts a deified ruler and the goddess Ishtar and with prisoners offering plates of fruit.

Treasures from the Babylonian Age from the Iraq National Museum include The Lions of Tell Harmal, dated at 1800 B.C., two large, snarling, terra-cotta lions that guarded the entrance to a temple at Tell Harmal, a site within Baghdad’s city limits. Most works described as Babylonian art are actually Neo-Babylonian art. See Below.

The most famous object from Babylon is the 8-foot black diorite stele of legal code of Hammurabi from the 18th century B.C. On the top of the stele Hammurabi is shown standing before Shamash, the god of justice, receiving the laws. The stele is believed to be one of many that were set up throughout the Babylonian domain to inform people of the law of the land. The Code of Hammurabi slab that exists today was moved to Susa in Iran in 1200 B.C. and discovered in 1901. It is currently at the Louvre.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Mesopotamia: Ancient Art and Architecture” by Bahrani Zainab (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Art and Architecture of Mesopotamia” by Giovanni Curatola, Jean-Daniel Forest, Nathalie Gallois (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient (The Yale University Press Pelican History of Art) by Henri Frankfort , Michael Roaf, et al. (1996) Amazon.com;

“Art of the Ancient Near East: A Resource for Educators” by Kim Benzel, Sarah Graff, Yelena Rakic Amazon.com;

“Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus”

by Joan Aruz and Ronald Wallenfels (2003) Amazon.com;

“Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C.”

by Joan Aruz, Kim Benzel, et al. (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Near East (Volume II): A New Anthology of Texts and Pictures”

by James B. Pritchard (1976) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Earth Architecture: Past, Present, Future” by Jean Dethier (2020) Amazon.com;

“Ziggurat: The Sacred Tower” by Theodor Dombart, Safaa H Hashim Amazon.com;

“House Most High: The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia (Mesopotamian Civilizations)

by Andrew R. George (1993) Amazon.com;

“Temples of Enterprise: Creating Economic Order in the Bronze Age Near East”

by Michael Hudson (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion” by Thorkild Jacobsen (1976) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Architecture: Mesopotamia, Egypt, Crete, Greece”

by Seton Lloyd , Hans Wolfgang Muller, et al. (1974) Amazon.com;

“Houses and Households in Ancient Mesopotamia”: Papers Read at the 40th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Leiden, July 5-8, 1993 (Pihans) Paperback – Illustrated, December 31, 1996 by KR Veenhof Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City“ by Gwendolyn Leick (2001) Amazon.com;

“Cornerstone: The Birth of the City in Mesopotamia” by Pedro Azara and Jeffrey Swartz (2015) Amazon.com;

“Early Urbanizations in the Levant: A Regional Narrative” by Raphael Greenberg (2002) Amazon.com;

Examples of Babylonian Art

Marduk was the chief god of Babylon and head of the later Babylonian pantheon. Found at Babylon, a lapis-lazuli cylinder, with dedicatory inscription to Marduk by Marduk-nadinshum, king of Babylonia (c. 850 b.c), was found in the temple E-Sagila at Babylon. The storm-god Adad (or Ramman) was also important. Found at Babylon, a Lapis-lazuli cylinder, with dedicatory inscription to Marduk by Esarhaddon, King of Assyria (680-669 B.C.), but nevertheless expressly designated as “the seal of Adad was also found at the temple E-Sagila,” and formed part of the treasury of Marduk.

The Diorite statue found at Telloh is now in the Louvre. The head was found by De Sarzec in 1881 and through the discovery of the body in 1903 by Captain Cros, the statue was completed. Ten other such diorite statues of Gudea (minus the heads) have been found at Telloh, covered with dedicatory and historical inscriptions.

The scene of Gilgamesh in the act of strangling a lion is frequently reproduced in a variety of forms on seal cylinders, and evidently represents one of his heroic deeds, though not included in the portions of the Epic that have up to the present been recovered. “A votive offering to the god Ningishzida. The elaborately sculptured design consists of two serpents entwined around a staff, backed by two fantastic figures, winged monsters with serpents’ heads and tails ending in a scorpion’s sting. Green steatite. Found at Telloh and now in

“A votive offering to his god Ningirsu, deposited in the temple E-Ninnu. The central design of which only one face is shown in the illustration consists of four lion-headed eagles, of which two seize a lion with each talon, and a third eagle seizes a couple of deer and the fourth a couple of ibexes. The eagle appears to have been the symbol of Ningirsu, while the lion, — commonly associated with Ishtar — may represent Bau, the consort of Ningirsu — the Ishtar of Lagash. The combination would thus stand for the divine pair. Dr. Ward (Seal Cylinders of Western Asia, p. 34 seq.) plausibly identifies this design with the bird Im-Gig, designated in the inscriptions of Gudea as the emblem of the ruler. This vase, considered to be the finest specimen of early metal work of Babylonia, was found at Telloh, and is now in the Louvre.

Neo-Babylonian Art

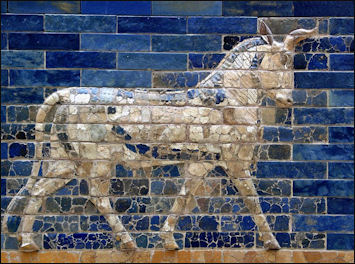

Neo-Babylonian buildings were decorated with with images of animals and creatures endowed with magical qualities: stout bulls, long-neck dragons and creatures composed of body parts of different animals. A mythical creature depicted with tiles on the Ishtar gate in Babylon from the Period of Nebuchadnezzar featured the head of a gazelle, the body of a lion, the tail of a snake. These images contrasted markedly from with the militaristic friezes of the Assyrians.

Ishtar Gate The Assyrians and the Neo-Babylonians were adept at making bricks and tiles with wonderful multi-colored glazes and decorations. Figures of winged bulls and serpents were placed at the entrance of a building to prevent the demons of evil from passing through it. Before the gates of Babylon Nebuchadnezzar “set up mighty bulls of bronze and serpents which stood erect,” and when Nabonidos restored the temple of the Moon-god at Harran two images of the primeval god, Lakhum, were similarly erected on either side of its eastern gate to “drive back” his “foes.” These protecting genii were known as sêdi and kurubi, the shédim and cherubim of the Old Testament. Sédi, however, was a generic term, including evil as well as beneficent genii, and the latter was more properly classed as the lamassi, or “colossal forms.” [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The most famous works of Neo-Babylonian art is perhaps the Ishtar Gate.The Relief of Lion (c. 585 B.C.) formed part of a processional way for the kings of Babylon. The lion represents the goddess Ishtar. The brilliance of the decorations symbolized power. The gate was named after the goddess and was a part of the procession way.

The magnificent Processional Way and Ishtar Gate from Babylon now lies Pergamonmuseum in Berlin, Germany. Built during the reign of Nebuchadnezar II, it taken piece by piece from Iraq between 1899 and World War II, rebuilt inside the museum. The magnificent crenelated walls of the gate and walkway are made of blue, gold and red tiled bricks and features rows and walking bulls, lions, dragons and long-necked dogs. Most of the bricks were made in Germany but the animals were pieces from original Babylonian bricks. A cuneiform inscription read, "Nebuchadnezzer, King of Babylon, the pious prince.

Treasures from the Neo-Babylonian Age from the Iraq National Museum include the world’s oldest intact library — 800 neo-Babylonian cuneiform clay tablets, dated to around 550 B.C., which contain early references to the Noah flood story; and tablets with Hammurabi’s Legal Code.

Ishtar Gate c.600 B.C.

The magnificent Processional Way and Ishtar Gate from Babylon now lies Pergamonmuseum in Berlin, Germany. Built during the reign of Nebuchadnezar II, it taken piece by piece from Iraq between 1899 and World War II, rebuilt inside the museum. The magnificent crenelated walls of the gate and walkway are made of blue, gold and red tiled bricks and features rows and walking bulls, lions, dragons and long-necked dogs. Most of the bricks were made in Germany but the animals were pieces from original Babylonian bricks. A cuneiform inscription read, "Nebuchadnezzer, King of Babylon, the pious prince.

Ishtar Gate Inscription (c.600 B.C.) is written in the Akkadian language on a glazed brick gate that is 15 meters high and 10 meters wide. The Dedication Inscription contains 60 lines of writing and was dedicated by Nebuchadnezzar King of Babylonia (reigned 605—562 B.C.), The gate was discovered in Babylon and was excavated between 1899—1914. It is currently in the Pergamon Museen in Berlin, Germany](Adapted from Marzahn 1995:29-30, [Source: Hanson's web page]) Ishtar Gate Inscription reads: Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylon, the faithful prince appointed by the will of Marduk, the highest of princely princes, beloved of Nabu, of prudent counsel, who has learned to embrace wisdom, who fathomed their divine being and reveres their majesty, the untiring governor, who always takes to heart the care of the cult of Esagila and Ezida and is constantly concerned with the well-being of Babylon and Borsippa, the wise, the humble, the caretaker of Esagila and Ezida, the firstborn son of Nabopolassar, the King of Babylon.

Both gate entrances of Imgur-Ellil and Nemetti-Ellil —following the filling of the street from Babylon—had become increasingly lower. Therefore, I pulled down these gates and laid their foundations at the water-table with asphalt and bricks and had them made of bricks with blue stone on which wonderful bulls and dragons were depicted. I covered their roofs by laying majestic cedars length-wise over them. I hung doors of cedar adorned with bronze at all the gate openings. I placed wild bulls and ferocious dragons in the gateways and thus adorned them with luxurious splendor so that people might gaze on them in wonder I let the temple of Esiskursiskur (the highest festival house of Markduk, the Lord of the Gods—a place of joy and celebration for the major and minor gods) be built firm like a mountain in the precinct of Babylon of asphalt and fired bricks.

Ishtar Processional Way

Hanging Gardens of Babylon

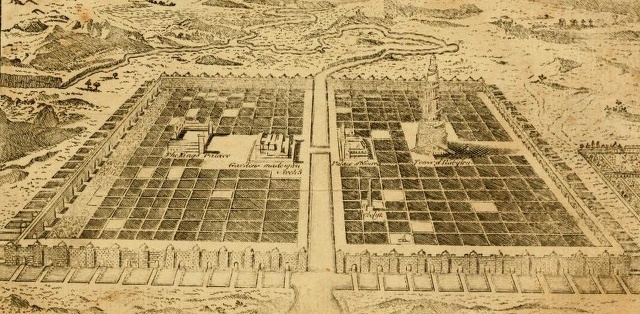

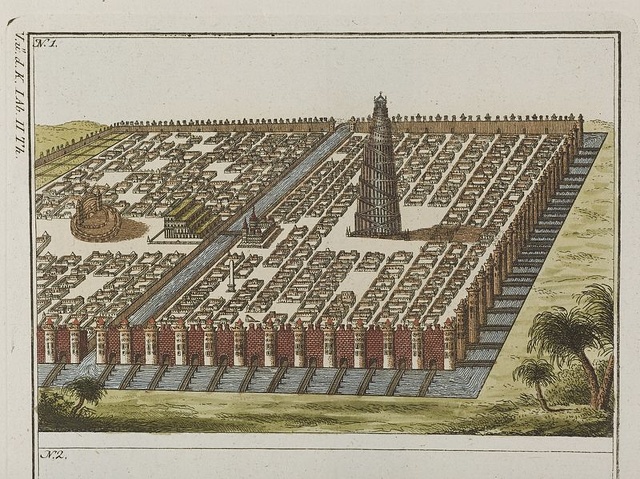

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were one of the Seven Wonders of the World. They are said to have been built in 600 B.C. by Nebuchadnezzar for one of his wives who had tired of the barren plains around Babylon and wanted a reminder of her lush mountainous homeland. The gardens were reportedly destroyed by several earthquakes after the 2nd century B.C. Some wondered whether the really existed. They were not even mentioned by Herodotus who visited Babylon when they are said to have existed.

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon may have inspired the story of the Garden of Eden. Based on descriptions that were written long after the gardens were said to have existed, the gardens were composed of gardens built on masonry terraces. They were called hanging gardens not because they were really hanging but because they seemed to hang.

The idea behind the Hanging Gardens of Babylon was to create a man-made mountain of lush vegetation. The result was believed to be a square building, 400 feet high, containing five terraces supported by arches that ascended upwards and were planted with grasses, plants, flowers and fruit trees, irrigated by canals and pumps worked by slaves and oxen. There was an avenue of palms. Water came from the Euphrates The queen set up her court inside surrounded by dense vegetation and artificial rain. There was said to be a terrace where she and Nebuchadnezzar sat, admiring their city.

See Separate Article: HANGING GARDENS OF BABYLON africame.factsanddetails.com

Babylonian and Assyrian Architecture

The architecture of Babylonia and Assyrians was dependent on the nature of their region. In the alluvial plain no stone was procurable; clay, on the other hand, was everywhere. All buildings, accordingly, were constructed of clay bricks, baked in the sun, and bonded together with cement of the same material; their roofs were of wood, supported, not unfrequently, by the stems of the palm. The palm stems, in time, became pillars, and Babylonia was thus the birthplace of columnar architecture. It was also the birthplace of decorated walls.

Hanging Gardens of Babylon

It was needful to cover the sun-dried bricks with plaster, for the sake both of their preservation and of appearance. This was the origin of the stucco with which the walls were overlaid, and which came in time to be ornamented with painting. Ezekiel refers to the figures, portrayed in vermilion, which adorned the walls of the houses of the rich.

The temple and house were alike erected on a platform of brick or earth. This was rendered necessary by the marshy soil of Babylonia and the inundations to which it was exposed. The houses, indeed, generally found the platform already prepared for them by the ruins of the buildings which had previously stood on the same spot. Sun-dried brick quickly disintegrates, and a deserted house soon became a mound of dirt. In this way the villages and towns of Babylonia gradually rose in height, forming a tel or mound on which the houses of a later age could be erected.

In contrast to Babylonia the younger kingdom of Assyria was a land of stone. But the culture of Assyria was derived from Babylonia, and the architectural fashions of Babylonia were accordingly followed even when stone took the place of brick. The platform, which was as necessary in Babylonia as it was unnecessary in Assyria, was nevertheless servilely copied, and palaces and temples were piled upon it like those of the Babylonians. The ornamentation of the Babylonian walls was imitated in stone, the rooms being adorned with a sculptured dado, the bas-reliefs of which were painted in bright colors. Even the fantastic shapes of the Babylonian columns were reproduced in stone. Brick, too, was largely used; in fact, the stone served for the most part merely as a facing, to ornament rather than strengthen the walls.

Babylonian Columns and Architectural Decoration

The upright palm stems of Babylonian, as we said, became columns, which were imitated first in brick and then in stone. Babylonia was thus the birthplace of columnar architecture, and in the course of centuries columns of almost every conceivable shape and kind came to be invented. Sometimes they were made to stand on the backs of animals, sometimes the animal formed the capital. The column which rested against the wall passed into a brick pilaster, and this again assumed various forms. The monotony of the wall itself was disguised in different ways. The pilaster served to break it, and the walls of the early Chaldean temples are accordingly often broken up into a series of recessed panels, the sides of which are formed by square pilasters. Clay cones were also inserted in the wall and brilliantly colored, the colors being arranged in patterns. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

But the most common form of decoration was where the wall was covered with painted stucco. This, indeed, was the ordinary mode of ornamenting the internal walls of a building; a sort of dado ran round the lower part of them painted with the figures of men and animals, while the upper part was left in plain colors or decorated only with rosettes and similar designs. Ezekiel 6 refers to the figures of the Chaldeans portrayed in vermilion on the walls of their palaces, and the composite creatures of Babylonian mythology who were believed to represent the first imperfect attempts at creation were depicted on the walls of the temple of Bel.

Among the tablets which have been found at Tello are plans of the houses of the age of Sargon of Akkad. The plans are for the most part drawn to scale, and the length and breadth of the rooms and courts contained in them are given. The rooms opened one into the other, and along one side of a house there usually ran a passage. One of the houses, for example, of which we have a plan, contained five rooms on the ground floor, two of which were the length of the house. The dimensions of the second of these is described as being 8 cubits in breadth and 1 gardu in length. The gardu was probably equivalent to 18 cubits or about 30 feet. In another case the plan is that of the house of the high priest of Lagas, and at the back of it the number of slaves living in it is stated as well as the number of workmen employed to build it. It was built, we are told, in the year when Naram-Sin, the son of Sargon, made the pavement of the temples of Bel at Nippur and of Ishtar at Nin-unu.

Herodotus on the Great Temple in Babylon

Herodotus wrote in “The History of the Persian Wars” ( c. 430 B.C.): “In the one stood the palace of the kings, surrounded by a wall of great strength and size: in the other was the sacred precinct of Jupiter Belus [Bel], a square enclosure two furlongs each way, with gates of solid brass; which was also remaining in my time. In the middle of the precinct there was a tower of solid masonry, a furlong in length and breadth, upon which was raised a second tower, and on that a third, and so on up to eight. The ascent to the top is on the outside, by a path which winds round all the towers. [Source: Herodotus, “The History”, translated by George Rawlinson, (New York: Dutton & Co., 1862]

“When one is about half-way up, one finds a resting-place and seats, where persons are wont to sit some time on their way to the summit. On the topmost tower there is a spacious temple, and inside the temple stands a couch of unusual size, richly adorned, with a golden table by its side. There is no statue of any kind set up in the place, nor is the chamber occupied of nights by any one but a single native woman, who, as the Chaldaeans, the priests of this god, affirm, is chosen for himself by the deity out of all the women of the land. I.182: They also declare — but I for my part do not credit it — that the god comes down in person into this chamber, and sleeps upon the couch. This is like the story told by the Egyptians of what takes place in their city of Thebes, where a woman always passes the night in the temple of the Theban Jupiter [Amon-Ra].

“In each case the woman is said to be debarred all intercourse with men. It is also like the custom of Patara, in Lycia, where the priestess who delivers the oracles, during the time that she is so employed — for at Patara there is not always an oracle — is shut up in the temple every night.I.183: Below, in the same precinct, there is a second temple, in which is a sitting figure of Jupiter [Marduk], all of gold. Before the figure stands a large golden table, and the throne whereon it sits, and the base on which the throne is placed, are likewise of gold.

“The Chaldaeans told me that all the gold together was eight hundred talents' weight. Outside the temple are two altars, one of solid gold, on which it is only lawful to offer sucklings; the other a common altar, but of great size, on which the full-grown animals are sacrificed. It is also on the great altar that the Chaldaeans burn the frankincense, which is offered to the amount of a thousand talents' weight, every year, at the festival of the God. In the time of Cyrus there was likewise in this temple a figure of a man, twelve cubits high, entirely of solid gold. I myself did not see this figure, but I relate what the Chaldaeans report concerning it. Darius, the son of Hystaspes, plotted to carry the statue off, but had not the hardihood to lay his hands upon it. Xerxes, however, the son of Darius, killed the priest who forbade him to move the statue, and took it away. Besides the ornaments which I have mentioned, there are a large number of private offerings in this holy precinct.” I.184:

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024