Home | Category: Jewish Sects and Religious Groups / Judaism and Jews / Jewish Customs, Languages and Life / Judaism, Jews, God and Religion

WHO IS A JEW

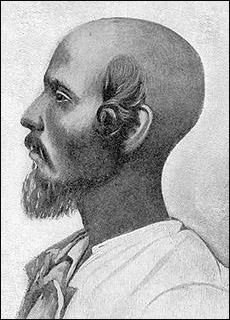

Cochin Jew in India in the 1800s The definition of a Jew is hotly contested issue in Israel. Traditionally, children of Jewish mothers have been recognized as Jewish. Conservative Jews insist that this is not enough: a true Jew is someone who keeps Jewish law and obeys the commandments. "Whoever saves a single Jew,” reads the Babylonian Talmud. "Scripture ascribes it to him as though he had saved an entire world.”

Some groups also accept children of Jewish fathers as Jewish. American reformed Judaism recognizes patrilineal descent. The State of Israel grants citizenship under the law of return to people with a single Jewish grandparent. Conservative Jews Chas Chabadniks accept only the Talmudic rule that a Jew is anyone born to a Jewish mother, or someone who has undergone an Orthodox conversion and agreed to keep all 613 Jewish laws. A Jew traditionally can't lose his or her technical 'status' of being a Jew by adopting another faith, but they do lose the religious element of their Jewish identity. Someone who isn't born a Jew can convert to Judaism, but it is not easy to do so."

Gershom Gorenberg wrote in the New York Times, “Judaism, traditionally, is matrilineal: every child of a Jewish mother is automatically considered a Jew. Zvi Zohar, a professor of law and Jewish studies at Bar-Ilan University, told me that in Judaism’s classical view of itself, Jews are best understood as a “large extended family” that accepted a covenant with God. Those who didn’t practice the faith remained part of the family, even if traditionally they were regarded as black sheep. Converts were adopted members of the clan. Today the meaning of being Jewish is disputed — a faith? a nationality? — but in Israeli society the principle of matrilineal descent remains widely accepted. Sharon’s mother was Jewish, so Sharon knew that she was, too. And yet it seemed impossible to provide evidence that would persuade the rabbinate. [Source: Gershom Gorenberg, New York Times, March 2, 2008 **]

“The rabbinic courts are an arm of the Israeli justice system. Formally, the judges — rabbis with special training — are appointed on professional grounds. In practice, positions in the courts and in the state rabbinate are parceled out as patronage by religious political parties. The main function of the rabbinic courts is divorce, also a purely religious process in Israel. A secondary function is providing judicial rulings on whether a person is Jewish. For that, the main clientele is immigrants from the former Soviet Union. A fairly standard procedure exists for them. It includes examining Soviet-era documents, like birth certificates, that list a citizen’s nationality. (In the Soviet system, “Jewish” was a nationality, parallel to “Russian” or “Uzbek,” listed in everyone’s official papers.) **

“Trust — or lack of it — is the crux. Zvi Zohar of Bar-Ilan University explained to me that historically, if someone said he was a Jew, “if he lived among us, was a partner in our society and said he was one of us, we assumed he was right.” Trust was the default position. One reason was that Jews were a persecuted people; no one would claim to belong unless she really did. The leading ultra-Orthodox rabbi in Israel in the years before and after the state was established, Avraham Yeshayahu Karlitz (known as the Hazon Ish, the name of his magnum opus on religious law), held the classical position. If someone arrived from another country claiming to be Jewish, he should be allowed to marry another Jew, “even if nothing is known of his family,” Karlitz wrote.” **

Jewish History Websites: Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“To Be a Jew Today: A New Guide to God, Israel, and the Jewish People”

by Noah Feldman Amazon.com ;

“Living a Jewish Life: Jewish Traditions, Customs, and Values for Today's Families” by Anita Diamant, Howard Cooper, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Choosing a Jewish Life, Revised and Updated: A Handbook for People Converting to Judaism and for Their Family and Friends” by Anita Diamant, Barrie Kreinik, et al. Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com ;

“The Gifts of the Jews: How a Tribe of Desert Nomads Changed the Way Everyone Thinks and Feels” by Thomas Cahill Amazon.com ;

“The Antiquities of the Jews”

by Flavius Josephus, Allan Corduner, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Jews: A History” by John Efron, Steven Weitzman, et al. Amazon.com ;

““The Origins of Judaism: An Archaeological-Historical Reappraisal” by Yonatan Adler Amazon.com ;

“"Early Judaism: A Comprehensive Overview" by John J. Collins and Daniel C. Harlow Amazon.com ;

“Essential Judaism: Updated Edition: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs & Rituals”

by George Robinson Amazon.com ;

“Living Judaism: The Complete Guide to Jewish Belief, Tradition, and Practice”

by Wayne D. Dosick Amazon.com

Jewishness and Genetics

.JPG)

Armenian Jews in Georgia Are light-skinned Jews from Eastern Europe, dark-skinned Jews from Yemen and black-skinned Jews from Ethiopia genetically related? Studies of blood types and some single-gene enzyme markers have shown that these groups have more in common genetically with people from their homeland than they do with other Jews. This suggests there has been a lot of intermingling, mixed marriages and conversions among Jews and Judaism is more of matter of faith than ancestry.

Studies of fingerprints, Rhesus blood group frequencies and other single-gene enzyme markers indicates the opposite. They show that Jews from different parts of the world have more in common with each other than each group does with non-Jews in their homeland. DNA studies have shown that Jews and Arabs have a common ancestor. Jews and Arabs also have a lot in common with other Mediterranean people.

Geneticists conclude that Jews from different parts of the world do have certain genetic similarities and some of the differences between them can be partly explained by changes that have occurred over the dozens of generations which they have been separated from each other. One study found that 40 percent of Ashkenazi Jews descended from just four women.

Many Jewish women lack a gene and genetic mutation associated with breast cancer. One doctor who has researched the matter told the Washington Post, “For most Jewish women the chance [of breast cancer ] is so low that we would not recommend testing unless they are red flags.” Ashkenazi Jews have an unusually high risk of certain cancer as as well as Gaucher and Tay-sachs diseases.

Conversion to Judaism

Judaism is not a missionary faith and so doesn't actively try to convert people (in many countries anti-Jewish laws prohibited this for centuries). Despite this, the modern Jewish community increasingly welcomes would-be converts. A person who converts to Judaism becomes a Jew in every sense of the word, and is just as Jewish as someone born into Judaism. There is a good precedent for this; Ruth, the great-great grandmother of King David, was a convert. [Source: BBC |::|]

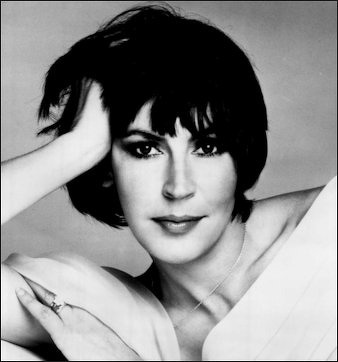

Jackie Wilson coverted to Judaism

According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: As a monotheistic religion affirming the oneness of God and thus of humanity, Judaism welcomes conversion. The classic example of the convert is Ruth the Moabite, who in accepting the God of Abraham declared, "For wherever you go, I will go; wherever you lodge, I will lodge; your people shall be my people, and your God my God" (Ruth 1:16). The fact that Ruth was the grandmother of King David, from whose descendants the Messiah is to emerge, underscores the esteemed status of the convert. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Until the destruction of the Second Temple, Judaism actively sought to proselytize. Thereafter, as a dispersed minority, missionary activity became difficult. Moreover, as they increasingly became subject to often aggressive Christian missionaries, Jews developed an aversion to active proselytizing. This attitude was reinforced by the Talmudic doctrine that "the righteous of all peoples have a share in the World to Come." Hence, a person need not be a Jew in order to be graced with God's love. All that is required of non-Jews is the observance of the seven Noahide Laws, the laws given to Noah and his "descendants," that is, all of humanity, after the Flood (Gen. 9:1–17): prohibitions against idolatry, blasphemy, murder, adultery and incest, robbery, and the eating of flesh torn from living animals (and by extension cruelty to animals), as well as the establishment of courts of justice. The rabbis considered these laws to be understood instinctively by all peoples. Nonetheless, sincere converts are welcome, their sincerity judged by a preparedness to accept the fate of the Jewish people and a commitment to observe the precepts and teachings of the Torah. The prevailing practice is to require the prospective convert to undertake an intensive course of study before submitting an application to a court of at least three rabbis.

According to the BBC: “Not all Jewish conversions are accepted by all Jews. The more Orthodox a community is the less likely it is to accept a conversion done in a more liberal movement. Orthodox Jews usually don't accept the validity of conversions done by non-Orthodox institutions - because many Orthodox Jewish communities do not accept that non-Orthodox rabbis have valid rabbinical status. |::|

“Why convert? The most common reasons put forward are: 1) because the person believes the faith and culture of the Jewish people is right for them; 2) in order to marry someone Jewish; and 3) in order to bring up children with a Jewish identity But only the first of these should be accepted as the true reason for conversion - the convert must have an overpowering wish to join the Jewish people and share in their destiny, and be committed to loving God and following his wishes as expressed in the Torah. There is no other reason that can enable a person to truly enter the covenant between God and the Jewish people, and do it freely, without reservation, forever, and to the exclusion of all other faiths. |::|

Conversion Process in Judaism

According to the BBC: “Converting to Judaism is not easy. It involves many lifestyle changes and about a year of studying. Becoming a Jew is not just a religious change: the convert not only accepts the Jewish faith, but becomes a member of the Jewish People and embraces Jewish culture and history. Conversion to Judaism is a process governed by Jewish religious law. Conversions are overseen by a religious court, which must be convinced that the convert: 1) is sincere; 2) is converting for the right reasons; 3) is converting of their own free will; 4) has a thorough knowledge of Jewish faith and practices’ and 5) will live an observant Jewish life.There are also two ritual requirements: 1) a male convert must undergo circumcision - if they are already circumcised, a single drop of blood is drawn as a symbolic circumcision; 2) the convert must undergo immersion in a Jewish ritual bath, a mikveh, with appropriate prayers. [Source: BBC |::|]

So did Helen Reddy

“Different forms of Judaism have different conversion mechanisms, but this outline of what is involved covers the basics for all: 1) discuss possible conversion with a rabbi; 2) study Jewish beliefs, history, rituals and practices; 3) learn some Hebrew; 4) get involved with Jewish community life; 5) believe in G-d and the divinity of the Torah; 6) agree to observe all 613 mitzvot (commandments) of the Torah; 7) agree to live a fully Jewish life; 8) circumcision (men only); 9) immersion in a mikveh or ritual bath; and 10) appear before a Bet Din (a religious court) and obtain their approval. |::|

“Conversion to Judaism is not something to be done lightly. The rabbi will want to make sure that the person really wants to convert, and that they know what they're doing. Some rabbis used to test would-be converts by turning them away three times, in order to see how sincere and determined they are. This is unusual nowadays. If a person doesn't know any rabbis to discuss conversion with, they probably haven't got close enough to Judaism and Jewish life to be thinking of converting. They should start by talking to Jewish people, and attending some synagogue services. |::|

“The rabbi asks the would-be convert a lot of questions - not just as a test of their sincerity, but in order to help the convert form a clear understanding of what they want to do: 1) Why do you want to convert? 2) What do you know about Judaism? 3) Are you converting of your own free will? 4) Have you discussed conversion with your family? 5) Will you accept Judaism as your only religious faith and practice? 6) Will you enter into the covenant between God and the Jewish people? 7) Will you bring up your children as Jews? 8) Are you willing to study in order to convert? 9) Will you live as a member of the Jewish people? Would-be converts study Jewish beliefs, rituals, history, culture (including some Hebrew) and customs. They do this through courses, or by individual study with a rabbi. At the same time they will start going to services, joining in home practices (with members of their local community) and taking part in synagogue life.” |::|

Reasons for the Confusion Who Is a Jew

Gershom Gorenberg wrote in the New York Times, “Several trends have combined to change that. In an era of intermarriage, denominational disputes and secularization, Jews have ceased agreeing on who belongs to the family, or on what the word “Jew” means. Ultra-Orthodox Jews increasingly question the Jewishness of those outside their own intensely religious communities. The flood of immigrants from the former Soviet Union to Israel deepened their doubts. In the Soviet Union, when someone with parents of two nationalities received identity papers at age 16, he could pick which nationality to list. A child of a Jewish father and non-Jewish mother could put down “Jew.” The religious principle of matrilineal descent was irrelevant. [Source: Gershom Gorenberg, New York Times, March 2, 2008 **]

“In the United States, the Reform movement responded to rising intermarriage by deciding in 1983 to accept children of a Jewish father and non-Jewish mother as Jews if they were raised within the faith. The denominations also diverge on how to accept a convert into Judaism. Orthodox Jews generally do not regard conversions by non-Orthodox rabbis as valid — either because the rabbis do not strictly follow religious law or because they do not require the converts to do so. The number of people in America “recognized by some movements as Jewish but not by others” is “certainly in six figures,” according to Jonathan D. Sarna, a Brandeis University professor and the author of “American Judaism: A History.” **

Polish converts to Judaism

“Denominational rules are only part of the story. In much of the world, Jewish identity has become fluid, part ethnicity, part religion, a matter of choice. “In the United States and also in Western Europe there are many kinds of Jews,” Prof. Menachem Friedman, a Bar-Ilan University sociologist of religion, told me. “People can change religions and identities quickly.” But in Israel, belonging has practical consequences: The 1950 Law of Return grants every Jew the right to immigration. In 1970, the Knesset defined the term “Jew” as meaning “one who was born to a Jewish mother or who converted to Judaism.” That was a partial victory for those demanding traditional religious criteria. But to keep the door open to those who didn’t fit that definition, the amendment also granted the right of immigration to the child, grandchild or spouse of a Jew. Each time religious parties sought to go further and define conversion by Orthodox rules, Sarna recounts, “American Jewry would go into crisis mode,” its leaders insisting that Israel couldn’t delegitimize the non-Orthodox denominations. **

“In 1986, the Israeli Supreme Court ordered the Interior Ministry’s Population Registry to list Shoshana Miller, a Reform convert from America, as Jewish on her ID card. The ultra-Orthodox interior minister resigned in protest. In practice, though, the rabbinate paid scant attention to ID cards. Couples registering to marry were asked to bring two witnesses who could testify that the applicants were Jews under Orthodox law. The two arms of the state, secular and religious, operated according to separate rules. **

“And in the rabbinate, power was shifting to the ultra-Orthodox — the wing of Judaism that segregates itself from the surrounding society and culture. In the early years of the state, those serving in the rabbinate generally identified with the project of building a Jewish state and felt a connection with secular Jews. Politics changed that. Thirty years ago, ultra-Orthodox parties held 5 of the 120 seats in the Knesset. Today, they hold 18. Secular politicians need their support to build a stable coalition government. One way to gain it is to back ultra-Orthodox candidates for rabbinic posts. It is one of the stranger alliances that politics can create: the secular politicians regard “Jewish” mainly as a nationality, an ethnic identity that includes both believers and nonbelievers. For the rabbis they have empowered, “Jewish” is exclusively a religious category, and secular Jews are at best estranged cousins.” **

Jews from the Soviet Union Confuse the Who is a Jew Issue Even More

Gorenberg wrote in the New York Times, “The true Era of Mistrust began in the 1990s, with the exodus of Jews from the Soviet Union. A semiclandestine agency called Nativ (Route) was responsible for checking whether would-be immigrants qualified under the Law of Return. To establish Jewish identity, the agency scrutinized Soviet documents. [Source: Gershom Gorenberg, New York Times, March 2, 2008 **]

Russian convert to Judaism

“At the state rabbinate, marriage registrars adopted their own policy of doubt. Increasingly, rabbinate clerks sent anyone not born in Israel, or whose parents weren’t married in Israel, to a rabbinic court to prove that he or she was Jewish. Rabbi Osher Ehrentreu, the official at the rabbinic courts responsible for checking Jewish status, can’t name a date for the change, which apparently emerged without an explicit decision. The courts sought the same kind of documents as Nativ did, like birth certificates of the applicant’s mother and maternal grandmother listing them as Jews. **

“The traditional willingness to trust a person who said he was Jewish, Ehrentreu asserts, presumed that no one had anything to gain by it. Today, he told me, there are ulterior motives — to be able to leave another country and come to Israel, “to be recognized here as Jewish, to be able to get married.” That is, Israel’s prosperity, its attractiveness to immigrants, is now a reason for doubt. Friedman, the reigning academic expert on ultra-Orthodox society in Israel, suggests that the deeper reasons for doubt are difficult for the rabbis to articulate. In contrast to Orthodox Jews like Farber, the ultra-Orthodox have little sense of risk that by raising doubts they might exclude a person who is really Jewish. “If you don’t keep the Torah and the commandments, O.K., so I excluded you. In any case you weren’t a complete Jew,” is how Friedman explains the attitude. **

“The policy of suspicion is applied to all immigrants. Rabbi Rasson Arussi, chairman of the Chief Rabbinate’s committee on marriage, told me that “populations where there is doubt about Jewishness” include those from Western countries, specifically “the sectors connected to Reform Jews.” The rabbinate’s expectations, however, are a poor fit with the United States. American Jews generally don’t have government papers testifying to their Jewishness. While a British Jew might turn to his country’s chief rabbinate for certification that he is Jewish, the very idea of a chief rabbi sounds outlandish in the United States.” **

Who Is a Jew Issue Particularly Acute for American Jews

Gorenberg wrote in the New York Times, “And as Farber points out, the reign of doubt at the Israeli rabbinate began as it was becoming steadily less likely that an American Jew would be able to dig an Orthodox marriage contract out of her mother’s drawer. In the generation after World War II, most American Jews moved away from even a nominal connection to Orthodoxy. Today, young American-born Jews are likely to be two or three generations removed from any tie with Orthodoxy. [Source: Gershom Gorenberg, New York Times, March 2, 2008 **]

“Strikingly, the rabbinate’s doubts extend even to Orthodox rabbis in America. “They’re not familiar with them,” Friedman told me. “They say: ‘The rabbis in the United States, in England, aren’t the kind we know. Someone can define himself as an Orthodox rabbi, but really he’s Reform.’ ” A marriage registrar given a letter from an Orthodox rabbi abroad certifying that a person is Jewish is now expected to check with the office of Chief Rabbi Shlomo Amar, which maintains a list of diaspora clergy whose letters are to be trusted. The list is not publicly available. If the rabbi who wrote the letter is not on the list, the applicant is asked for other proof or referred to the rabbinic courts. **

“Converts, even the children of converts, potentially face greater difficulties, because the rabbinate has also become more skeptical about Orthodox conversions performed abroad. What’s more, under pressure from Chief Rabbi Amar, the main association of Orthodox clergy in the United States, the Rabbinical Council of America, is establishing its own regional rabbinic courts for conversion. A recent council position paper warns that the group makes no commitment to stand behind conversions performed by other rabbis. The paper also stresses that converts are expected to accept Orthodox religious law, or Halakhah. **

“The policy has divided the American group. Advocates say that standardization will ensure that converts are accepted by all religious Jews. A former council president, Marc Angel, a sharp critic, told me the group “decided to capitulate” to Amar and robbed individual rabbis of their prerogative to measure the needs and commitment of prospective converts. “The rabbinate in Israel has put the Orthodox rabbinate” — meaning Orthodox rabbis in the United States — “on the same level as Reform rabbis,” Angel said. He now advocates a position once unthinkable among R.C.A. rabbis: Israel would be better off if it instituted civil marriage and cut the state’s ties with the rabbinate. **

“Not surprisingly, leaders of non-Orthodox denominations in the United States sound both pained and vindicated when discussing the rabbinate’s policies. “There is quite an irony in this,” Rabbi Eric H. Yoffie, president of the Union for Reform Judaism, told me. In the past, “Orthodox authorities in America have basically defended the system, and they’ve embraced this religious monopoly as being important and necessary, thinking all the while that it was directed primarily against us, us meaning the non-Orthodox community.” Now their own bona fides are in doubt. **

“Arnold M. Eisen, chancellor of the American Conservative movement’s Jewish Theological Seminary, stresses the damage to Israel-diaspora relations: “All the data shows a growing rift between American Jews and Israeli Jews, and the younger you are as an American Jew, the less that you care about the state of Israel. This is just terrible. And one of the reasons for it — not the only reason, but one of the reasons for it — is this kind of insulting treatment of the majority of American Jews by the Israeli rabbinate.”“ **

Ultra-Orthodox Contest Jewish Conversions

Griff Witte wrote in the Washington Post, “Over the past decades, Israel has admitted hundreds of thousands of immigrants from the former Soviet Union, over the objections of ultra-Orthodox leaders who spoke out against allowing non-Jews to enter the country. Many of the immigrants lacked the paperwork to prove their Jewish ancestry. Others had fathers or grandparents who were Jewish, but did not qualify as Jewish themselves because Judaism is passed down through mothers. Until now, ultra-Orthodox leaders have not acted as forcefully to invalidate immigrant conversions. [Source: Griff Witte, Washington Post, September 2, 2008 ]

“On one side are ultra-Orthodox leaders who are using their long-standing dominance of Israel's rabbinical court system — which has authority over marriages, divorces and conversions — to tighten restrictions governing who can become Jewish. They see themselves as defending the religious purity of a people who, according to their interpretation of Jewish law, need to live apart from other groups.

“Those on the other side are much more concerned with demographics: They believe that at a time when the number of Arabs living between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea is poised to surpass the number of Jews, Israel needs all the converts it can get. This group includes secular Jews, but it is led by the religious Zionists, who form the core of the settlement movement in the occupied territories and who feel it is their duty to populate the biblical land of Israel. To Ish-Shalom, facilitating conversion has been good for the converts, good for Judaism and good for the state. "Israel needs people. It needs loyal people," he said.

“The ultra-Orthodox, Ish-Shalom argues, are damaging that effort by requiring converts to heed strict standards. Ultra-Orthodox leaders don't disagree. They believe that God originally expelled the Jews from the land of Israel because of their lack of religious devotion and that the secular nature of the modern Israeli nation is unacceptable. As a result, many are anti-Zionist. "There's something more important than the state of Israel and Zionism," said Moshe Gafni, a member of Israel's parliament who represents the ultra-Orthodox United Torah Judaism party. Wearing the customary ultra-Orthodox uniform of black pants and white shirt, Gafni speaks forcefully and with deep conviction: "Unlike Christians, we Jews are not missionaries. If someone really wants to join the Jewish people, we're going to make it difficult for them."

“Gafni's view is rooted in his interpretation of Jewish law. To him, there are two kinds of Jews: those who were born of Jewish mothers into the faith, and those who can prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that they are willing to abide by Jewish law and accept the hundreds of mitzvoth, or commandments, that govern an observant Jew's daily life. To admit others, he said, would be to destroy the integrity of a community that, according to God's will, needs to stay distinct. “While the ultra-Orthodox are only about 11 percent of Israel's Jewish population — approximately the same share as the religious Zionists — they have wielded increasing power in recent years as high birth rates swell their numbers. Ben-Moshe said he expects them to double their share of the Jewish population within the next 20 years.

Israeli Jewish Converts Told They Are Not Jews

Griff Witte wrote in the Washington Post, “ Yael converted to Judaism in 1992, and for the next 15 years she lived in Israel, celebrating the major holidays and teaching her children about the Jewish faith. But when she and her husband sought a divorce last year, she said, the ultra-Orthodox rabbis in charge of the process had some questions. Among them: Did Yael observe the Sabbath? Did she obey the prohibition on sex during and after menstruation? Dissatisfied with the answers, the rabbis nullified her conversion. Yael did not need a divorce, they ruled, because she had never been married. She had never been married because she had never been Jewish. And because she had never been Jewish, her children were not, either.

"I was in shock. I couldn't believe it," said Yael, 43, who would allow only her Hebrew name to be published out of privacy concerns. Blond, blue-eyed and athletic-looking, Yael is baffled by the ordeal. "My kids grew up Jewish," she said. "They don't know anything else." [Source: Griff Witte, Washington Post, September 2, 2008 ]

Bar Refaeli, a blonde, light-eyed Israeli

“Yael's personal trauma has become a cause for Israeli soul-searching over what it means to be Jewish, a term that carries both religious and ethnic dimensions. The case has set off a roiling debate between those who see themselves as saving Judaism and those whose first priority is to safeguard the Jewish state. The stakes have escalated since Yael's conversion was tossed out: When she appealed to the High Rabbinical Court of Israel, it not only upheld the original decision but also threw into doubt the legality of thousands of other conversions.

"There is a cultural war going on between various segments of Jewish society," said Benjamin Ish-Shalom, chairman of the Joint Institute for Jewish Studies. A trim man with a philosophical bearing who relishes any discussion of Judaism, he helps administer a government-funded education program for Israelis who need help getting through the rigorous process of conversion. Over time, the ultra-Orthodox have grown bolder in challenging the Israeli government's efforts to convert non-Jewish immigrants.

“Unwittingly, Yael became a part of that campaign when her husband filed for divorce. A Protestant by birth who grew up in Denmark, she moved to Israel in 1988 to be with her Jewish boyfriend. Because there is no civil marriage in Israel, she needed to convert to marry him here. The process took a year of intense study of Jewish prayers, holidays and traditions. "Ordinary Israelis don't know half of what I learned," she said while sitting at her kitchen table in this city by the Mediterranean. Like most ordinary Israeli Jews, her level of observance was not up to the standards of the ultra-Orthodox.

“Still, she had no idea that her conversion could be nullified — especially 15 years after the fact. In their 51-page decision, the rabbis in Ashdod who heard the divorce petition wrote that "most of the converts lie to the rabbis when they promise to keep the mitzvoth after the conversion. . . . How can one bury one's head in the sand and continue letting into the vineyard of the Jewish people these total non-Jews?" Yoseph Sheinin, chief rabbi of Ashdod, did not take part in the ruling, but he praised it as a means of correcting the government's mistakes. "The idea of Zionism was to bring Jews here. The moment they brought Gentiles here, they bankrupted the movement," he said.”

In 2021, Israel's Supreme Court Says Non-Orthodox Converts Are Jews

In March 2021, Israel's Supreme Court dealt a major blow to the country's powerful Orthodox establishment, ruling that people who convert to Judaism through the Reform and Conservative movements in Israel are also Jewish and entitled to become citizens. Associated Press reported: “The landmark ruling, 15 years in the making, centered around the combustible question of who is Jewish and marked an important victory for the Reform and Conservative movements. These liberal streams of Judaism, which represent the vast majority of affiliated American Jews, have long been marginalized in Israel. “If the state of Israel claims to be the nation-state of the Jewish world, then the state of Israel must recognize all the denominations of Judaism and imbue them with equality and respect,” said Rabbi Gilad Kariv, head of the Reform movement in Israel and a candidate with the liberal Labor Party in upcoming parliamentary elections.[Source: Laurie Kellman, Associated Press, March 2, 2021]

“Israel's powerful ultra-Orthodox establishment has held a virtual monopoly on religious matters for Israeli Jews, overseeing life-cycle rituals like weddings and burials and using their political clout to gain influence over matters like immigration. The ruling on conversion chipped away at that power by saying that the state must allow Jews who undergo conversions with the liberal movements in Israel to receive citizenship. “Jews who during their stay in Israel were legally converted in a Reform or Conservative community must be recognized as Jews,” the court said in its majority decision. It said the ruling only applied to the question of citizenship, and did not delve into religious affairs. Israel previously recognized conversions by the liberal streams conducted overseas. This ruling now applies to conversions inside Israel.

The ruling does not resolve the issues faced by people who qualify for citizenship under the so-called Law of Return but are not considered Jewish under religious law. The Law of Return grants citizenship to anyone with at least one Jewish grandparent, while religious law requires one to have a Jewish mother. These different definitions have allowed tens of thousands of people, mostly from the Soviet Union, to immigrate to Israel, only to suffer from discrimination when seeking religious services from the state.

The conversion ruling only directly affects about 30 people a year, such as spouses of Israeli citizens, advocates say. But both supporters and opponents of the decision suggested there was much deeper symbolism. “It’s saying that the Jewish world is one,” said Nicole Maor, the lawyer who represented the Reform movement. “Whoever becomes Jewish in a Reform conversion or something similar is not Jewish,” said David Lau, one of Israel's two chief rabbis. “No ruling by the Supreme Court this way or that way will change this fact.” The ultra-Orthodox are key allies of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu with great political power.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

ext Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024